Bruce Gilden: True to Himself on the Streets of Tokyo and Osaka

The photographer shares stories of tough encounters and unexpected beauty from his time spent in Japan

Bruce Gilden’s new book Cherry Blossom brings together the best images from his long-term project in Japan —published in Go (2000)— with 34 previously unseen photographs. It’s available to buy here.

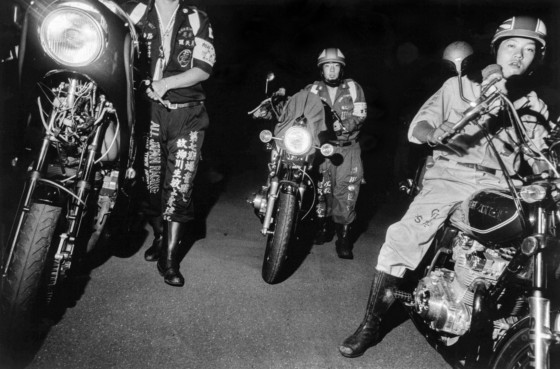

In this Q&A, Gilden reflects on his trips to Japan of the late 1990s, talking through some of his best shots, recalling the fights he got in with Yakuza members, and explaining how he made a genuine, personal work on the streets of Tokyo and Osaka.

What was your conception of Japan before you got there?

My understanding came from studying photographic history. As a young photographer, I was constantly looking at as many foreign photography magazines, books or reviews that I could find to see what everyone who was there before me had done. I would try to figure out what lenses they used, where they stood, or what subjects they photographed, and of course, I knew of postwar photographers in Japan. Then I saw the work of the most reknowned of them— Shomei Tomatsu, Masahisa Fukase, Eikoh Hosoe, and Daido Moyiama —at the exhibition ‘New Japanese Photography’ at MoMA in 1974. The show had a real emotional impact on me.

I saw that many of these photographers were influenced by William Klein or Ed van der Elsken, some of the photographers who had worked in Japan. But what I liked about this was that, even if some of them borrowed their style from other photographers, they had done a fantastic, personal job and some of their images blew me away.

"Street photography is basically a young man’s game. And I’m older now — I’m 74. So I can’t bend as low, but I haven’t changed: I’m still interested in taking the same kind of picture as I always did."

- Bruce Gilden

My conception of Japan was what I saw in the pictures. I don’t overthink things before I go to a country, or read too much about it. I don’t want to be influenced by someone else’s opinions, but after I went there, like for example in Haiti, I read tons of books on Haiti. I have some historical and some contemporary references just to see if my views are similar to other people’s views or if I’m missing something. And I did the same thing with Japan. The only problem with that for me was that when I arrived in 1994, it wasn’t the Tokyo of 1960 anymore. The country had changed. So I looked thoroughly all around Tokyo seeking out the subjects I would be visually interested in photographing.

I had started collecting photobooks at the time, so I took with me a list of books and traveled all over the city to find them, and came back home with a very nice collection.

Finally, in Tokyo, I met some of these Japanese photographers whose work I had seen at MOMA, and it’s funny, because I met more photographers in Tokyo than in New York, Paris or London!

Who else did you meet?

I was friendly with Eikoh Hosoe. He had given me a show at his school and they bought some prints and invited me over to lecture in Tokyo. He was very supportive. I would have dinner with him occasionally in Tokyo when I was there. I couldn’t meet Fukase because he was like a vegetable at the end of his life. He threw himself down a flight of stairs, or he fell. And if you look at his work you could see that he could end up like that. I liked the violence in his pictures… Whether he took them of his wife, pigs, or ravens, they were all about violence and death.

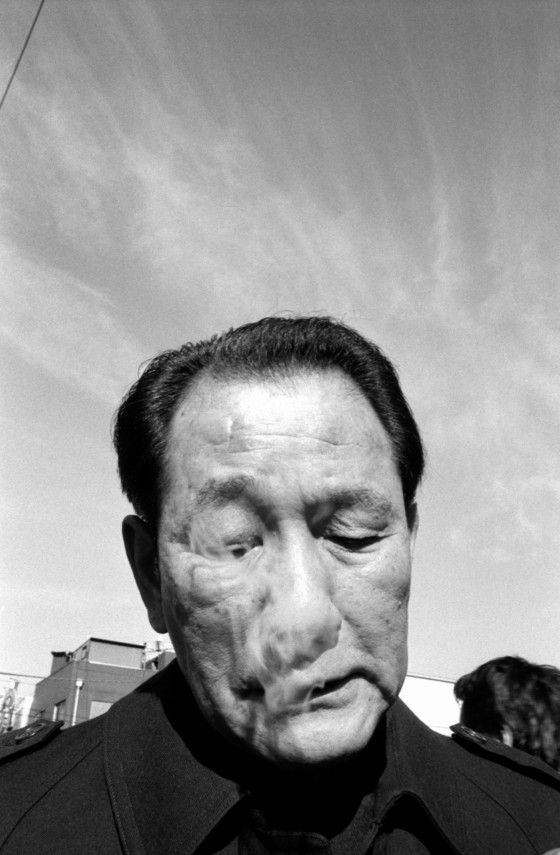

Among the people I photographed, there was George Abe, the ex-yakuza who later became a writer. I had lunch with him and he told me some fun stories like when he had an altercation once with the actor Robert Mitchum, who used to be a boxer, and Abe said that the actor knocked him out!

Why did you name the book Cherry Blossom?

I like picking out specific details. My first book made from my Japan photographs was called Go, which is a board game. When I was in Osaka I went to a big warehouse where there were day laborers congregating, along with homeless and lots of pigeons. Some people would play the game Go together in smaller room in the warehouse. And I named that book after it but there was nothing to do with it inside the publication.

What I liked about ‘Cherry Blossom’ was that, in one of the pictures I’ve taken, there’s the lady in a kimono depicted during the cherry blossom period. She’s wearing this kimono and she’s eating fried chicken.

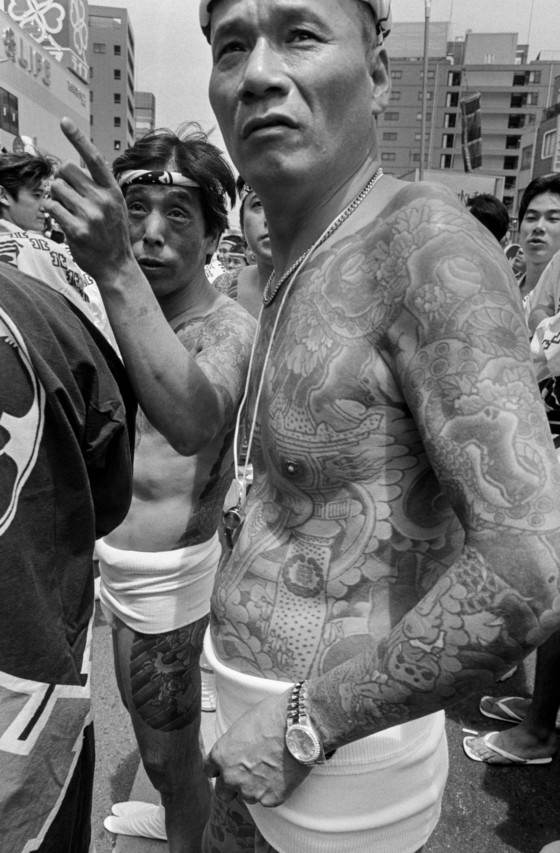

People will pick up the book and they’ll say, “Oh, Cherry Blossom — Bruce Gilden did cherry blossoms?” Then you open it up and you see the pictures of the subjects that interest me, which are yakuza, homeless, mostly all kinds of characters. Street photography is basically a young man’s game. And I’m older now — I’m 74. So I can’t bend as low, but I haven’t changed: I’m still interested in taking the same kind of picture as I always did.

Could you talk us through your process reviewing the images for the book and show us some pictures that didn’t make it originally into Go?

I think photographically, this book is better than Go. To decide on the selection for this book, I just went back over my work and I picked images that I saw were very strong. There are three images that I originally wanted to put in to Go, but which I got after the book was designed.

"My pictures are slices of life."

- Bruce Gilden

There’s this picture of the two persons — one of them is a cross-dresser, one is holding a beer — that I took when I was in an alley in Asakusa. I like it a lot. During my travels, I found all the places I photographed just by walking around the city. A particularly interesting place which I knew to go to was Asakusa, which is a more traditional area on the weekend. I would go to this alley where you had a lot of characters: there were yakuza that were down on their luck, and sometimes there were not very nice people. I saw these two and took the picture. It’s a strong image and could have been in the first book without a problem.

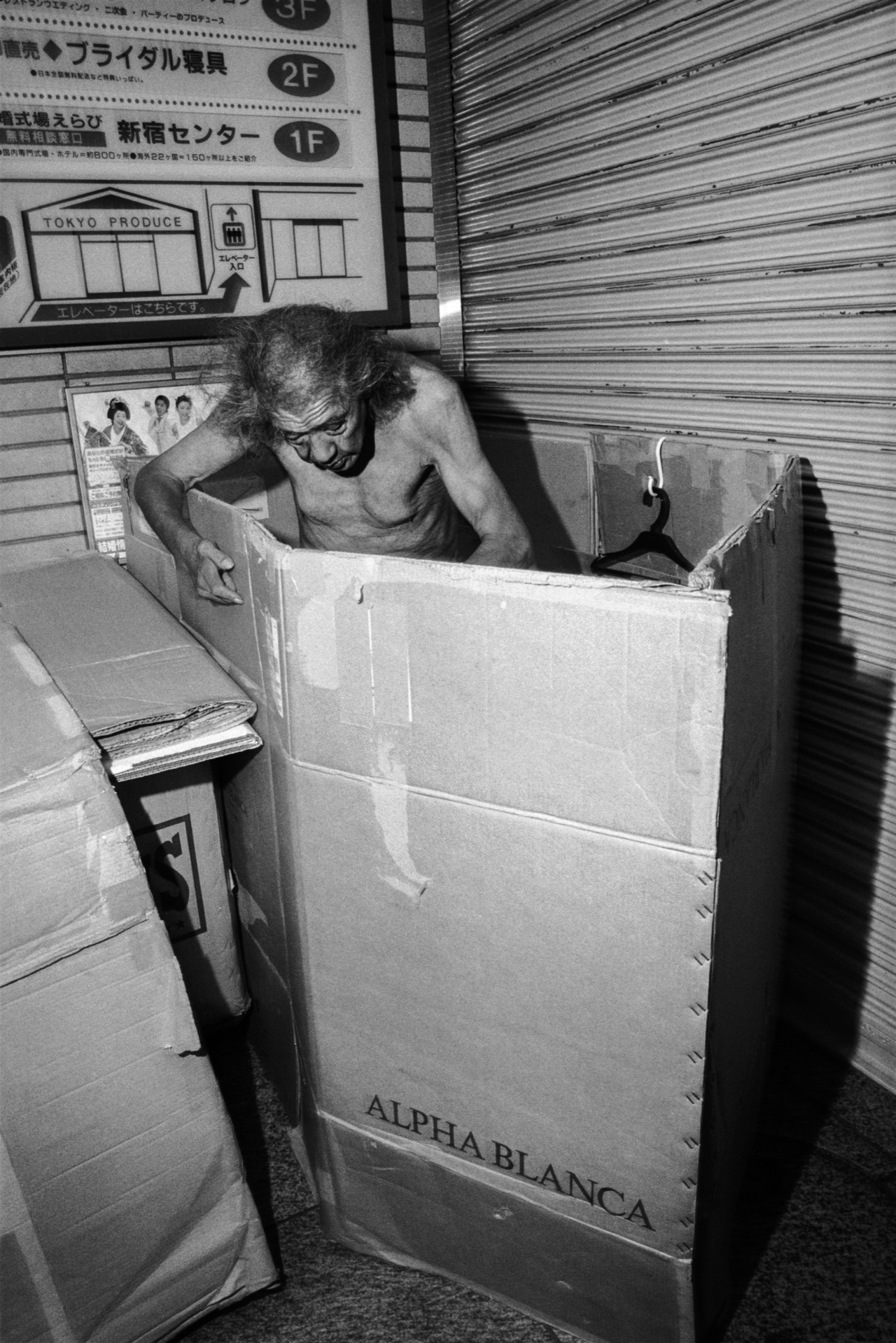

There’s a picture of a homeless man who slept in a cardboard box. I liked this one a lot, but it wasn’t ready in time for the book. I was out photographing early in the morning, and it must have been about 8AM when I took this picture. It was amazing for me to see so many homeless in Japan who kept their belongings so neat. A lot of them lived in Shinjuku, near the train station, on the underground level, in front of closed shops. Before they got thrown out they used to have very tidy spaces, with their clothes on coat hangers and little libraries filled with books. It was like they had their own open-air apartments. I never noticed it before, because I didn’t look that carefully, but this man’s got a hanger up. Look how clean he looks. And, you know, he lives in a little box and I guess he has to move that box unless that store was always shut. This one also would have been in the first book also, but it wasn’t ready in time.

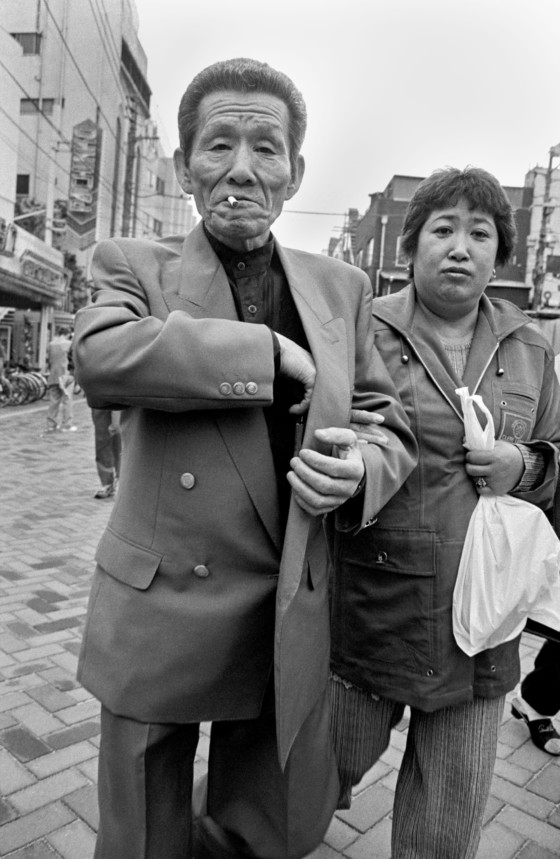

The third photograph is one that I really like very much because it has the most beautiful light. There’s a homeless woman and a homeless man, the light on their faces are glowing from my flash. He’s got like a turban on his head and a cigarette in his mouth. That’s a very beautiful picture for me.

What I like about these pictures, all three of these pictures, is the angle I’ve taken them. Angles are very important to me. I like the indecisive moments and when candid pictures are too perfect, I find that it looks almost staged. My pictures are slices of life. The subjects I photograph are always very elegant and the picture well formed. That’s why I do a lot of fashion photography because I have a very good eye for textiles and I know how to form a picture. To me, a good photograph should be well formed and have strong emotional content.

In that last shot, you can definitely feel a connection with the woman’s face.

I like very often when my subjects are looking in my direction, because I like photographing people who have an intensity or something in the eyes that says something to the viewer.

The funny part is that is that before I went to Japan I hadn’t realized there would be so many homeless people but then I started to think, and I figured that anywhere where there’s a lot of rich people, you’re going to have a lot of poor people. So it’s quite obvious that would be a lot of homeless in Japan. In America, I never photographed homeless people but in Japan I just found them interesting.

What would you say are the similarities or differences between making street photography in Tokyo and New York?

In Tokyo, a lot of times people don’t pay attention: they prefer not to have an argument with you, though that’s not always true with yakuza types. In New York, people would be prone to look at you or maybe say something to you.

Another thing is: the more connected that people around the world become, the less their cultures will remain what they naturally were for a long time. Now, a lot of people from Japan, Korea, and other countries are able to travel. I remember my first appointment in Tokyo was with a very good writer on photography. He said he had travelled to New York and I asked, “What’d you think?” He said, “Oh, it’s the third world!” And I laughed.

It seemed to him like the third world because there’s so many different kinds of people there. To me, it’s normal. I was born in Brooklyn to a father who was a gangster type. I often think you are who you are. I’m not apologetic to my background, because it made me what I am, for better or for worse.

Is this book on Japan true to yourself?

All of my images are personal. They’re all about me. That’s who I know. And that’s what I’m interested in. I work on intuition and the backgrounds and details are very important to me: it all has to come together. Of course, some pictures are better than others but I’ve always photographed who I am.

As Robert Frank wrote, “It’s important to see what’s invisible to others”. If you don’t look at the things I look at, how can you help people? You know, people may say they care, but they don’t look. You can’t sit behind your desk and tell me about the world. I’m out in the world. Like, now, I’m working in tough areas in Brooklyn a lot. So, you know, that’s what I’m interested in — real people.