Magnum On Set: Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight

W. Eugene Smith's photographs capture the icon of early cinema as a reflective, older man, at times struggling with difficulties both personal and professional

Magnum photographers have, over more than seven decades, captured pivotal moments in popular culture as much as historic events and societal sea changes. Working behind the scenes on sets of many classic films, they have captured not only iconic stars at various stages of their careers, but also documented the changing nature of cinema and film production. Sets, equipment, and special effects that once seemed futuristic are, with the passing of time rendered disarmingly romantic.

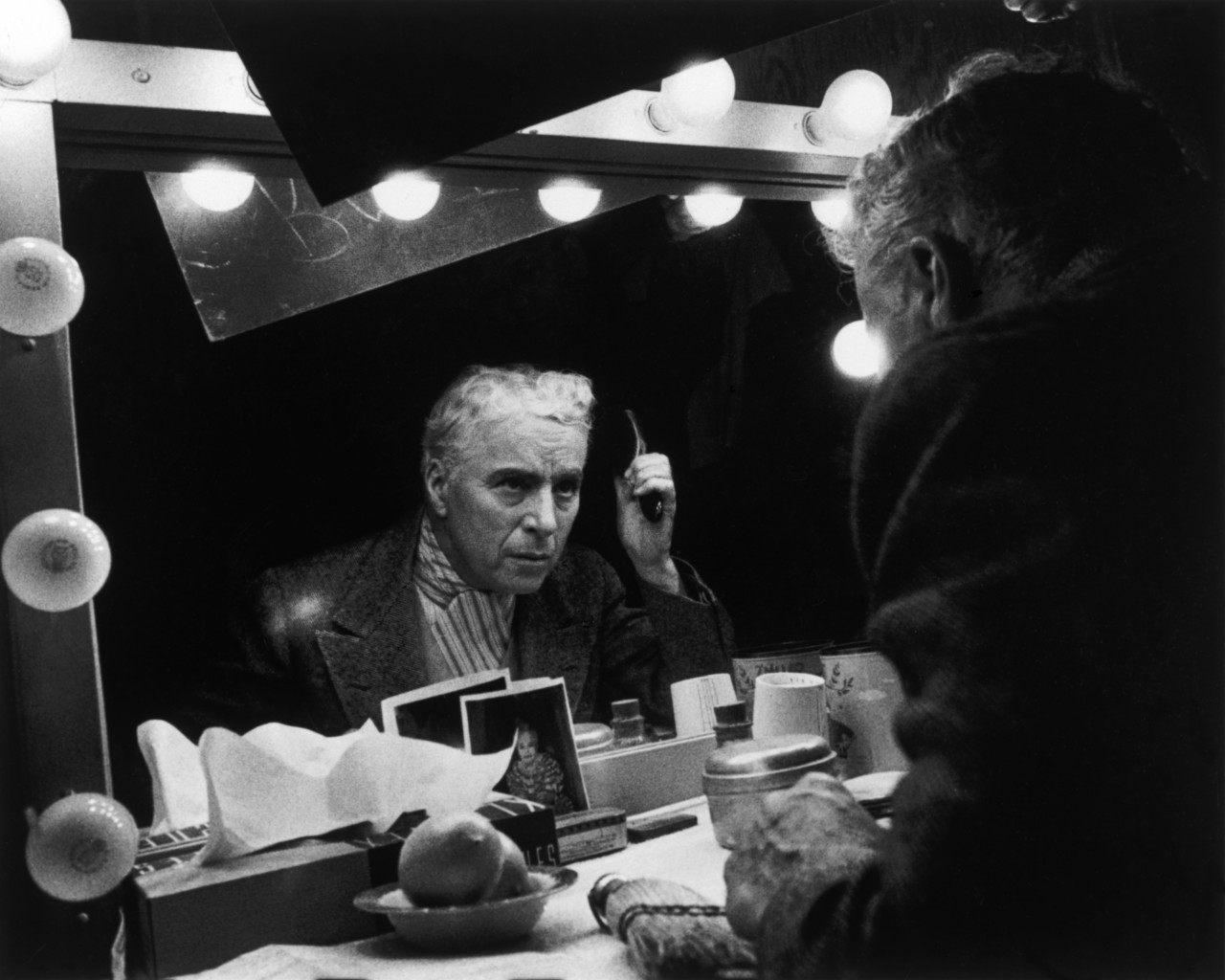

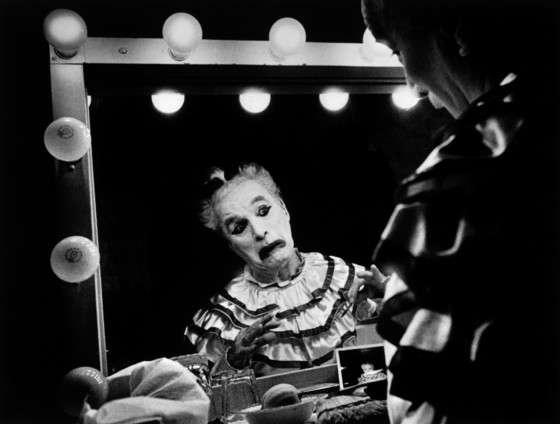

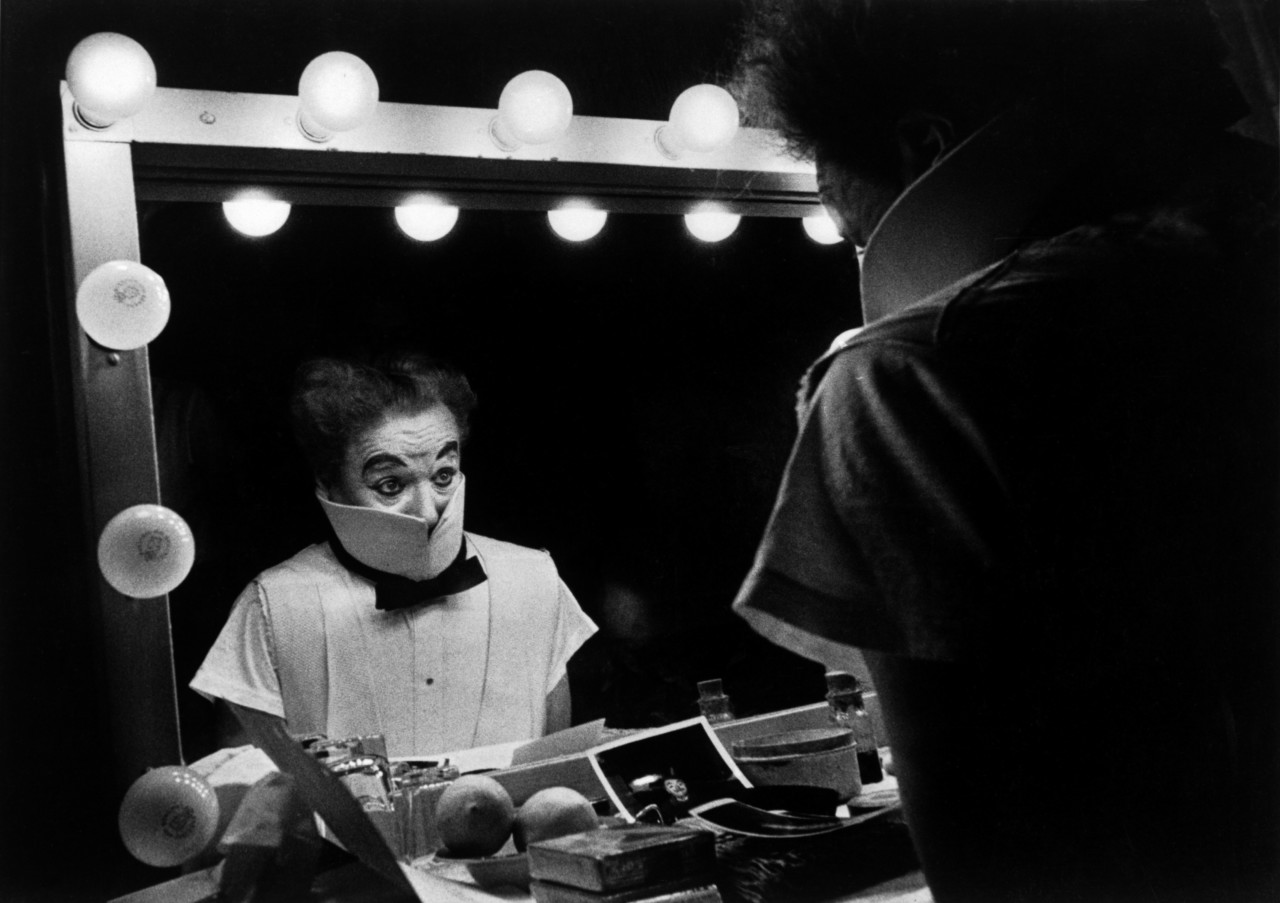

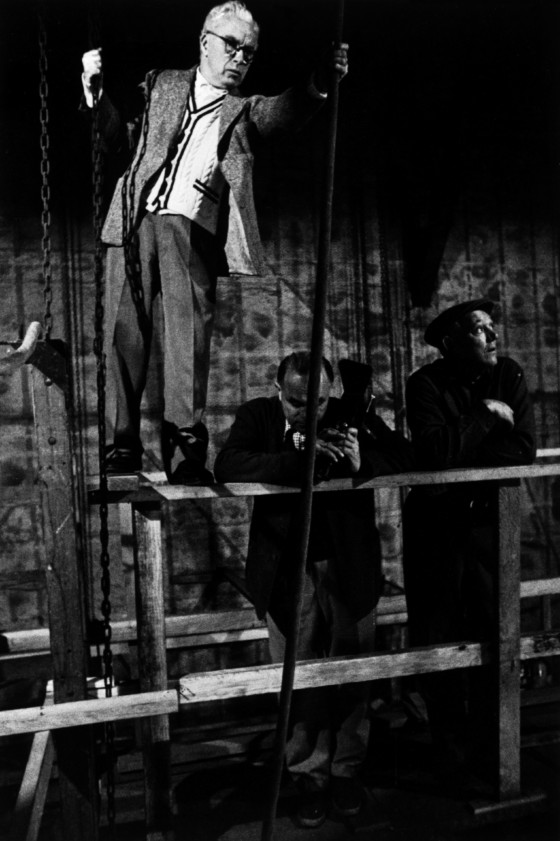

Here, we look at W. Eugene Smith’s photographs made on the set of Charlie Chaplin’s movie Limelight. The photographer captures Chaplin in full, familiar, on-set swing as well as documenting quieter moments where the performative mask seems to slip.

You can see other stories in the Magnum On Set series, here.

In 1951, photographer W. Eugene Smith travelled to Los Angeles on a five-week assignment for LIFE Magazine: to document Charlie Chaplin during the filming of his movie Limelight. Smith, who according to photography journalist Sean O’ Hagan, “was perhaps the single most important American photographer in the development of the editorial photo essay,” was the ideal photographer to capture Chaplin’s most personal project.

The photographer had come to his craft shortly after his father’s suicide. Smith was still a young man just out of high school, yet he made a personal vow that he would uphold throughout his career: “to hold himself to the highest standards of truth no matter the cost.” It is no surprise, therefore, that Smith’s on-set photographs made during the production of Limelight depict an often harried Chaplin bearing the weight of both filmmaking and troubles in his personal life.

Smith depicts Chaplin directing, performing, and behind the scenes with his family. Sometimes he even appears off-guard, almost in a state of reflection as he possibly contemplates his life up to this point. At this time in his life, Chaplin was striving to retain his relevance in an fast-changing industry. After fighting back against the introduction of sound with the critically acclaimed City Lights in 1931, his satirical turn as Hitler in The Great Dictator (1940) had left a sour taste. Concurrently, accusations were circulating of Chaplin’s involvement in anti-American activities, and his U.S. visa was voided after he left the country for Limelight’s London premiere. Furthermore, a paternity suit with up-and-coming actress Joan Barry had resulted in a loss of audience faith. Yet rather than bow to the pressure and make another political film, in 1952 Chaplin made Limelight, his most reflective and personal piece of work.

Based on his novella, Footlights, Limelight centres on Thereza “Terry” Ambrose, a dancer whose attempt to commit suicide is prevented by Calvero, a down on his luck drunk who was once a celebrated clown. Through caring for Terry, Calvero regains his self-confidence and sense of self-worth and eventually returns to the stage for one final, fatal, show. Throughout the film, there are nods to Chaplin’s personal life: his fall from grace, his relationship with a younger woman, and even a turn from the iconic Buster Keaton as his old partner. In one photograph, they stand side-by-side as Keaton gestures to the violin Chaplin is playing in a behind the scenes moment.

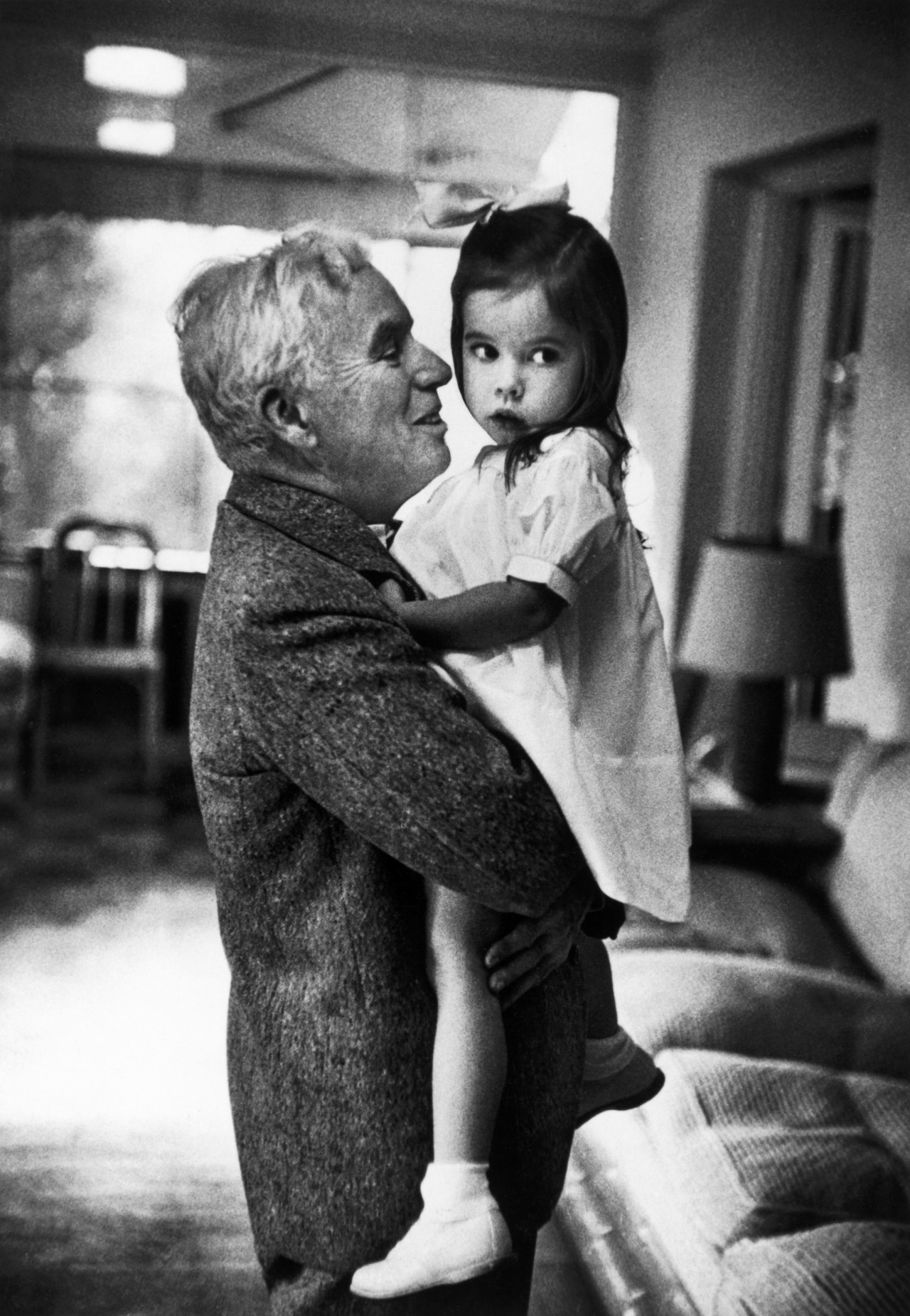

A few years before filming, Chaplin had married his protege Oona O’ Neill. At 18 years of age, their thirty six-year age gap only increased the snowballing speculation and controversy surrounding the once lauded actor. However, this would prove to be Chaplin’s most stable, contented union. Of the eight children the pair had together, many became actors, including Geraldine and Michael, while Victoria became a circus performer, fulfilling her father’s long-abandoned professional desire. We see a paternal side of Chaplin in one photo when he holds daughter Josephine, two years old at the time, in his arms: her brow is fuddled, slightly perplexed by the environment, while he only beams with pride at his toddler.

Despite the overall positive reviews, some critics regarded Limelight as an a attempt at a redemption story, evidence of Chaplin striving to make amends. Europe’s reaction was receptive and positive, while America was the most critical. Yet there was no doubting the sincerity Chaplin was striving to achieve. “What Mr. Chaplin is telling in this film” said Bosley Crowther in a 1952 edition of The New York Times, “is simply a tale of a great comedian of the English music halls who has gone to seed, yet who passes on to a young ballet dancer his vast abundance of courage and hope. That is what he is telling as the author, producer and director of the film—and also as the composer of the music, of one ballet and the comedy routines. But as its principal performer, he is not only playing the role; he is feeling it in its essence and projecting it from the screen.” Smith would be key in capturing the internality of Chaplin’s performance as he worked to project this sincerity onto the screen, and the physical and mental toll this took on Chaplin as a filmmaker and performer. His on-set expressions can be seen veering between intense, almost crazed determination in some photos and silent resignation in others. In some photographs, he can be seen sleeping on-set while still wearing full makeup and costume.

Smith’s photographs are, above all, moving, and perfectly highlight the passing of time. Chaplin is no longer the youthful, rambunctious street urchin twirling his cane, but cuts an almost sombre figure. Sitting at the mirror, we see him duck into his oversized collar, tilt his head and frown, and looked resignedly at his own reflection. Maybe it is a moment of contemplation for his life up to this point, all of his troubles and tribulations, the slight smirk on his face interpreted as either resignation or self victory. Perhaps it is Calvero who is staring back at him—the merging of fact and fiction. It reminds us of Smith’s intention to document to the truth of the image and reveal what was hidden. Is this the real Chaplin we are seeing? Only he himself would ever know the real answer.