Magnum On Set: Orson Welles’ The Trial

Nicolas Tikhomiroff's timeless photographs offer a behind the scenes look at the production of Orson Welles' disorienting 1960s classic

Magnum photographers have, over more than seven decades, captured pivotal moments in popular culture as much as historic events and societal sea changes. Working behind the scenes on sets of many classic films, they have captured not only iconic stars at various stages of their careers, but also documented the changing nature of cinema and film production. Sets, equipment, and special effects that once seemed futuristic are, with the passing of time rendered disarmingly romantic.

Here we look back onNicolas Tikhomiroff‘s work on the set of Orson Welles’ adaptation of Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial.

You can see other stories in the Magnum On Set series, here.

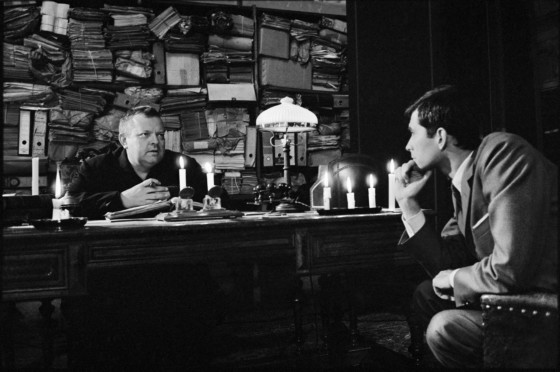

Having started his career working in the darkroom of a fashion photographer, Nicolas Tikhomiroff – born in Paris to Russian emigre parents – carried out editorial assingments in conflict zones in Algeria and South East Asia, but was ultimately to become perhaps best-known for his photographic work on cinema. As TIME wrote in the photographer’s obituary, “His images bridged the cultural distance between the razzle-dazzle of 1960s film and the growing turbulence of social change.” Among his myriad portraits of the glamorous stars of (and the minds behind) many of cinema’s golden age greats are his photos of Orson Welles, with whom the photographer became close. Some of his best-known portraits of Welles were made on the set of The Trial.

Welles’ adaptation of Franz Kafka’s book, also titled The Trial, was noted for it’s unusual use of focus and disorienting framing and camera angles – with one of Welles’ own biographers, Charles Higham, describing watching it as “an agonizing experience.” However – given that Kafka’s novel – somewhat typically – focused upon an individual protagonist’s maddening struggle through an obscure and labyrinthine legal system, one might assume Welles’ creation of this sense of agonizing disorientation was fully intentional.

The film’s plot sees a man – known only as Josef K. – awaking in his bedroom to be informed of his nonspecific crimes by men claiming to be policemen but bearing no proof of identity. From this unsettling start K. is informed on further occasions of his impending trial, again for unspecified crimes, and as a result he seeks the advice of a recommended advocate, Albert Hastler. Ultimately this meeting is of little use, and K. is apprehended by a pair of executioners, who – after some deliberation – kill him. Neither K. or the viewer ever discover the nature of the crimes he is accused of.

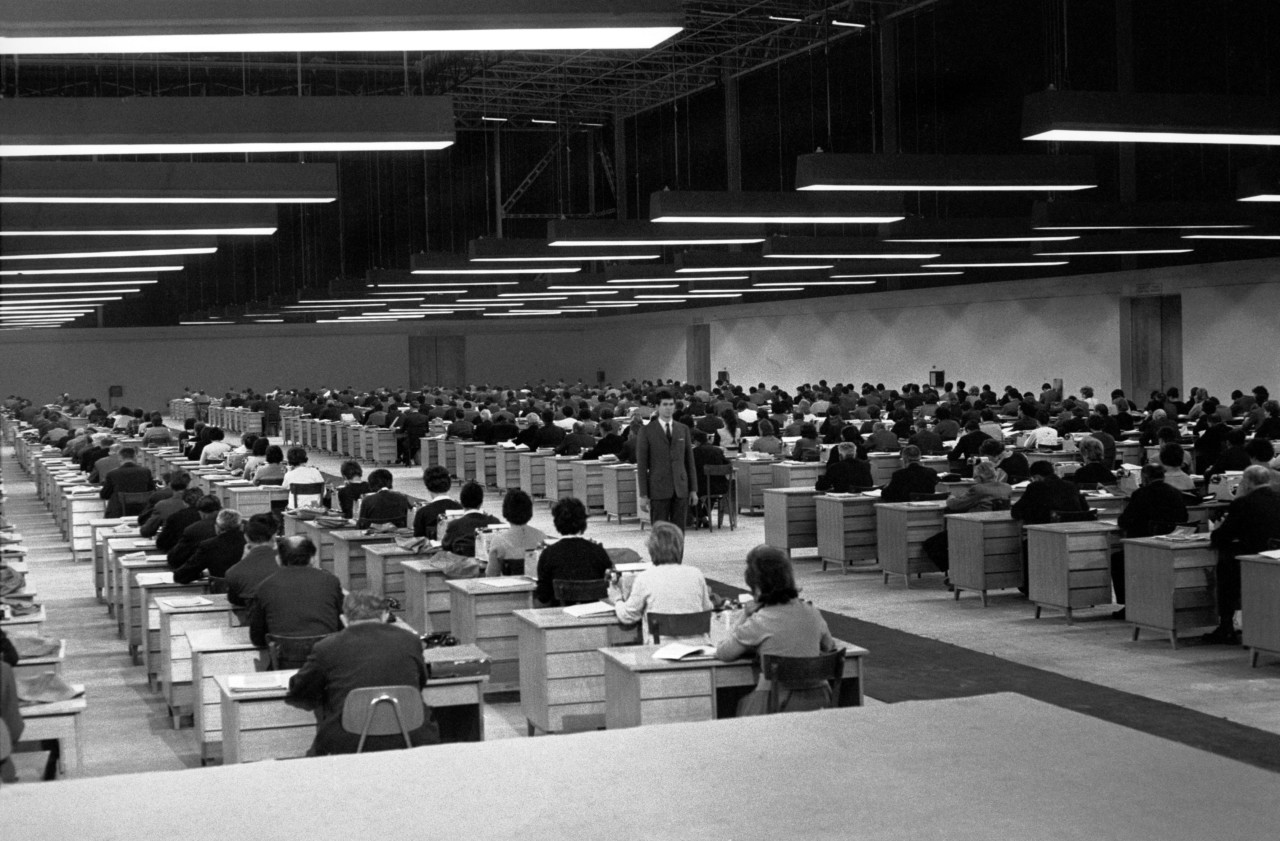

As well as writing and directing the film, Welles also played the role of advocate Hastler. Franco-German actress Romy Schneider played Hastler’s mistress Leni, while Anthony Perkins (freshly catapulted to international fame by Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 classic Psycho) depicted the accused, K.. Welles’ interpretation of Kafka’s existentialist masterpiece saw numerous tokens of modernisation: Josef K’s workplace (originally a bank where he was a cashier) was depicted on celluloid as a grand hall, lined with repeating – indeed almost infinite-seeming – banks of typewriting secretaries, and his mode of death shifted from a fatal stab to the heart to a decidedly more kinetic explosion followed by a (thoroughly 1960’s) mushroom cloud.