Emerging in Fragments: Sim Chi Yin’s ‘One Day We’ll Understand’

Max Houghton writes on the photographer’s solo show exploring histories of anticolonial resistance

An exhibition of the work ‘One Day We’ll Understand’ by Sim Chi Yin and curated by Sam I-Shan debuted this week at the photography festival Rencontres d’Arles 2021. The work shows at the Abbaye de Montmajour in Arles, France, until September 26, 2021, before travelling to Berlin’s Zilberman gallery in a new installation curated by Lotte Laub.

The project examines colonial and postcolonial accounts of the Malayan Emergency of 1948–1960, fought between communist guerrillas and Britain. To undertake this inquiry, Sim combines her archival findings from the Imperial War Museum in London and documents of alternative histories via her own photography and video works. In this essay, writer, curator and academic Max Houghton engages with the project.

The melodic strain of tremulous voices reverberates around the ancient walls of L’Abbaye Montmajour. Their timbre is reedy but purposeful; lyrics sometimes stumbled over, half-remembered. The tune registers … isn’t it The Internationale? The language remains, to some, unfamiliar. It is this fragmented musical memory that transports the viewer to another continent, another century, another act of resistance that would once have risked the lives of the singers. This polyphonic seepage sets the scene for an unsettling temporal journey, into what the artist Sim Chi Yin describes as ‘an unspoken archive about an undeclared war’, referred to by the British as the ‘Malayan Emergency’. At once situated in 1940s ‘British Malaya’ and contemporary Malaysia, Interventions animates the colonial archive to tell untold stories; to hear the silenced voices of the anti-colonial communist uprising, and to render palpable how British rule shattered the lives of hundreds of thousands of families, including her own, through subjugation, deportation and execution.

An image of a ruin opens the exhibition, rendered into flickering, jerky video. The form hints at the temporal disjunctures that characterise the effects of colonial rule, while the hollow structure of the destroyed building tells its own story, in the long lineage of fallen empires. Picturing time is always and never achieved in a photograph. Despite the instantaneity of its capture, or clues proffered by the studium, the concept of time passing eludes the stillness and silence of the frame. The archival image, when transported into the present, promises to do some of that work, and yet, such sharp delineation between then and now may not reveal ongoing incursions, which, while spectral, are vividly real, in the sense that such ghosts continue to ‘produce material effects1.’ Further, archival images per se may not offer the kind of interpretive space necessary to apprehend racial time2. In seeking to impart the filtrations of time and violence, Sim’s aesthetic strategy is to lay bare the operative logic of the colonial archive – ‘the first law of what can be said3’ – and to engage in a series of reversals at the level of photographic form.

"Surprising divisions become manifest on the plane of the image; brown sepia tones are drawn into an otherwise black and white world; a form of through-the-looking glass writing obscures the sky."

-

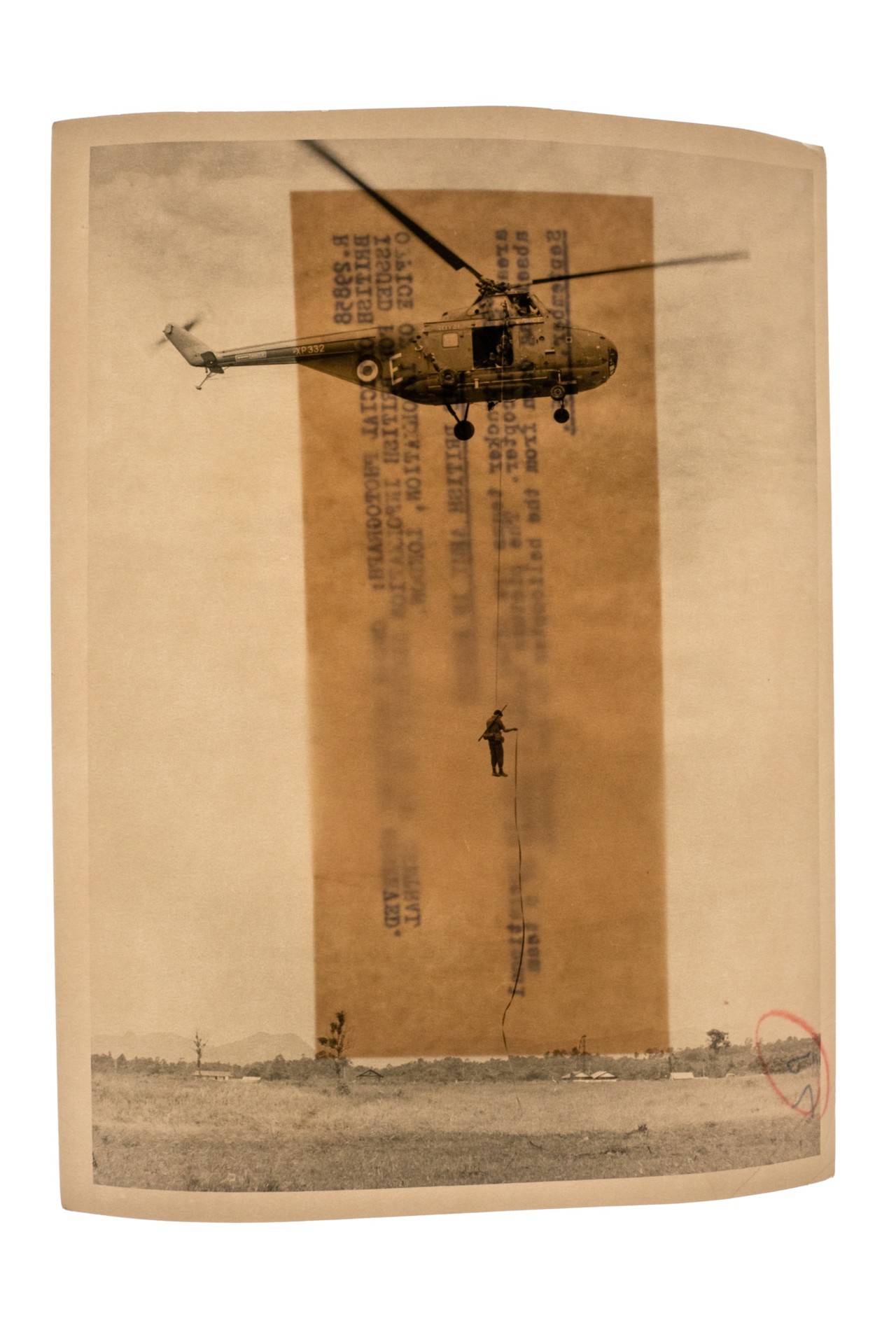

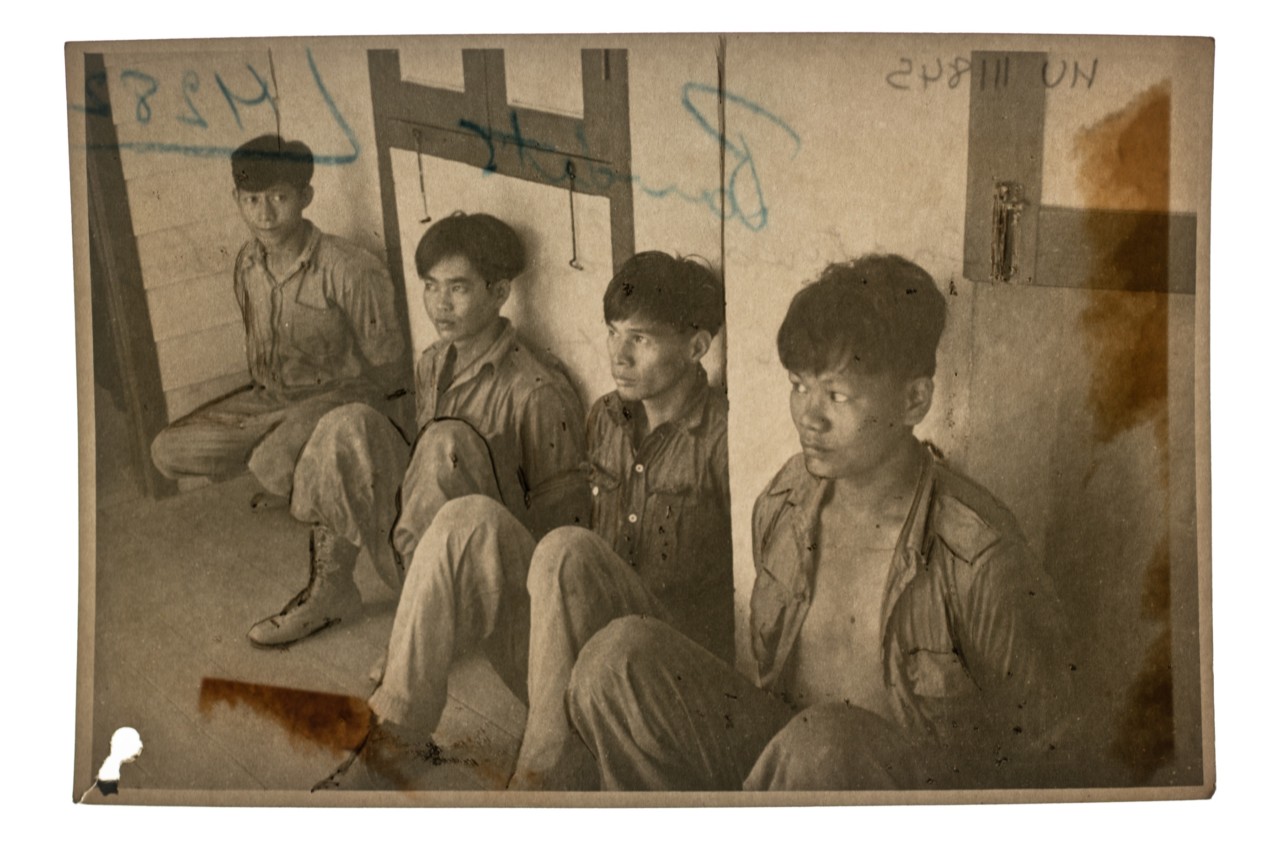

She uses a lightbox on which to photograph the archival images, drawn from Imperial War Museums’ collection, to reveal the layers of mark-making enacted on them, which in turn hints at how knowledge is formed, through strata of image and text. The eye can track absences through the shape of punch holes, or observe the stroke of blue wax, of sharp black ink outlines, framing the subject according to the relentless logic of colonial power. This technique is rich in its revelations: surprising divisions become manifest on the plane of the image; brown sepia tones are drawn into an otherwise black and white world; a form of through-the-looking glass writing obscures the sky. Sim’s astute eye offers every trace as a metaphor for governmentality.

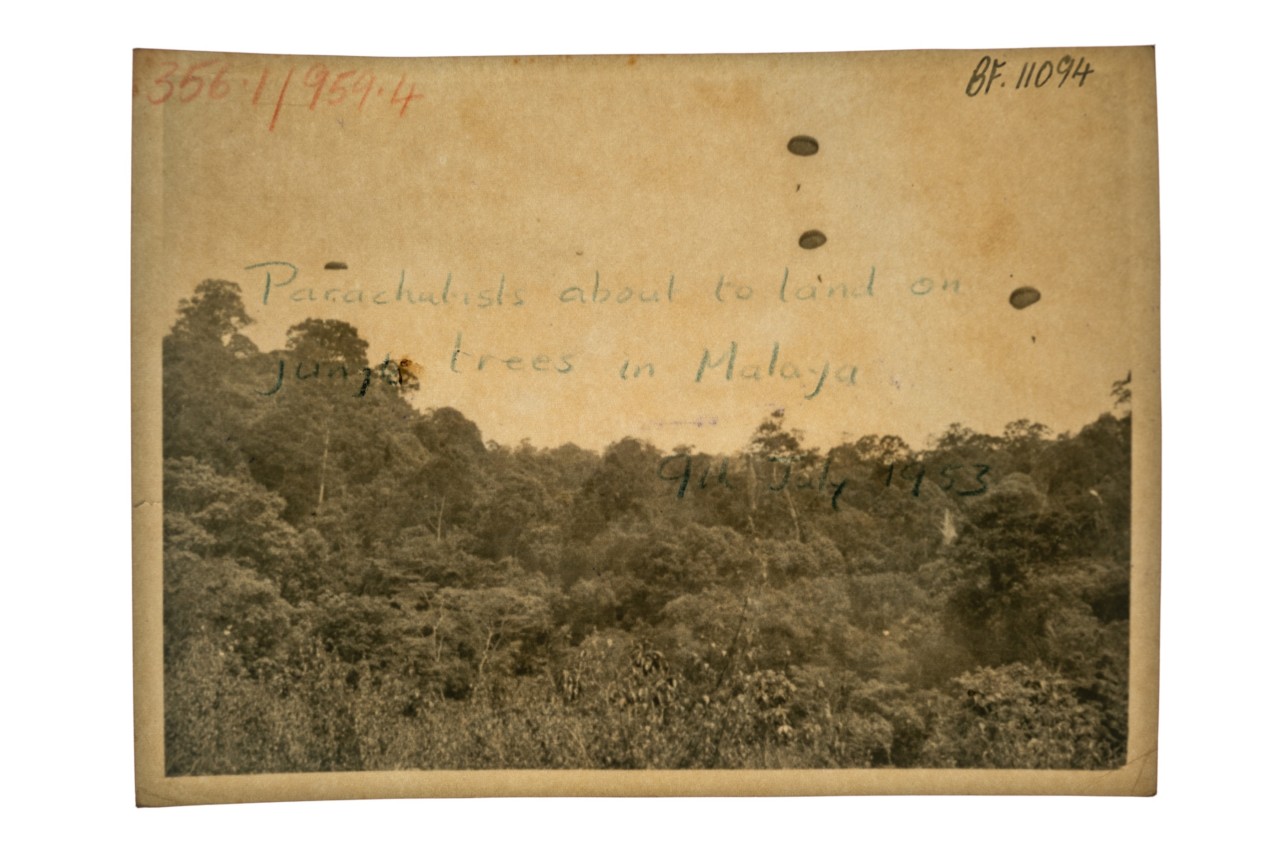

For the most part, in the selection of archival images, she has chosen to work with landscape, in part borne of an ethical imperative to avoid showing either colonial might or injured Asian bodies … though both tropes are rendered visible here; perhaps an inevitable consequence of using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house4. Images of vegetation recur, as though ‘the master’s’ eye could not wrest itself away from this uncontrollable jungle landscape. This is the same earth where a toxic herbicide was employed by the British, in a foreshadowing of the use in Vietnam of the almost-identical deadly defoliant known as Agent Orange.

The British operation in Malaya was subsequently understood as a training ground for how to deal with insurgencies; indeed, specific tactics appear in manuals for military incursions into Iraq and Afghanistan. Visual synergies emerge across time and space: the resonance of the suspended figure between the helicopter and the ground mobilises thought back to the events of 11 September 2001 in the United States, and the spectacle of the falling man. There is no forgetting that image, which became instantly ‘iconic’, such was the public outcry for this violation upon American soil. Similarly, the extraordinary image in this work of four imprisoned men, on the floor of a traditional Malayan wooden house, speaks to images from the cache of 198 declassified ‘torture’ images from the episode in American military history defined by extraordinary rendition, waterboarding and other forms of torture. Detained without trial in so-called ‘black sites’, the term ‘terrorist’ was swiftly conferred on men conforming to a specific racial category and political ideology. Shadowy images pictured blindfolded detainees in a state of waiting; fates unknown. Sim and the curator Sam selected just four archival images of the people whose bodies bore military force for this show. As a result of the intervention, each body is pictured riven with colonial language – words such as ‘terrorist’ and ‘bandit’ are just about legible, backwards and reversed – and divided by its own rule of terror. The searching eyes of these men in Malaya seem to insist upon a future spectator’s attention they could never have foreseen.

Sim’s own photographs focus predominantly on landscape too, created at sites of familial and political import. An image of a poignantly empty table and chairs signals, through its absences, the half million people resettled into camps, divided along political and racial lines; another precursor to Vietnam; specifically the ‘strategic hamlets’ policy. She photographs a ‘river of blood’, as it was locally known, because of bodies thrown into it, which at the same time carries a reminder of the time her great-grandmother said she ‘wished to cool herself’ in the water, understood as a euphemism for a strong wish to die. This is a clue to another absence, which haunts this exhibition: that of Sim’s deported leftist grandfather, whose life she commemorates in One Day We’ll Understand, and who was subsequently executed in China. Her grandmother, whose silence on the subject of her late husband wholly configured the life of her five children, is the impetus for a new work, She Never Rode that Trishaw Again, which weaves family archival images with a script of familial anomalies, questions and reminiscences. The legacies of colonial rule are far-reaching, embedding estrangements, confusion and states of indeterminacy into families who were subjected to it and continue to be shaped by it.

Of Sim’s photographic contribution, two further images are particularly haunting. A baby elephant is captured in motion; its shape so instinctive a child might have drawn it, yet, captured here in the darkness, it loses all meaning. Though in its natural habitat, the animal is rendered ghostly, uncanny, symbolic of all that may be hidden in plain sight. A further contemporary image depicts rubber trees at night. Almost hallucinatory, it offers itself as dark twin to an archival image, in which rubber trees have been drained of their essential sap by communist insurgents. The flapping white bark is ominous; redolent of Chinese funeral flags. The focus on these ‘natural histories’ within Sim’s work points to the insidious breadth of colonialism’s biopolitical reach, formed within its rubber plantations and tin factories, and extending far into the earth.

The final three archival images in the show offer a different kind of reversal. Drawing on self-representation, as is also evident in the two-channel video of the communal singing, is an essential element of what this work is pushing towards. The concept of the group is crucial here, united against the colonial oppressors; not rendered insignificant or abject. However, that discourse is abruptly upended, with this show’s specific atrocity image, of a dead insurgent, a corpse propped up on a ladder. He can only have been dragged there. Such images belong to the trope of trophy images, and its considered inclusion here serves as a multiplier of the violences enacted on a population, in the first instance on its bodies and in the second in representations, circulations and repetitions. This image is not attached to the wall but rests in an upturned plinth, which doubles as a kind of open grave.

Interventions brings a significant materiality to the concept of the archive, adding a strata of what can be felt, as well as what can be seen and said. In this necessarily reparative practice, in reading the archive against the grain, the old stories lose their legitimacy as the silenced voices rise ever higher, creating new constellations of knowledge. In yet another reversal, as the wheels of revolution continue – however slowly – to turn, the work also activates a significant immateriality, in teaching us how to observe the rents in the fabric of time, or, how to listen to ghosts.

Find information about the exhibition here.

[1] Gordon, A F, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (University of Minnesota Press 2008) pp17

[2] Sealy, M, Decolonising the Camera: Photography in Racial Time (Lawrence and Wishart 2019)

[3] Foucault, M, The Archaeology of Knowledge (Pantheon Books 1972) pp 129

[4] Lourde, A, ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’ in Your Silence Will Not Protect You (Silver Press 2017)