Ernest Cole: Lost and Found at Cannes

A new film by Raoul Peck uncovering the life, work, and legacy of the late photographer and activist wins top documentary prize.

“It will take generations to decipher and grasp your legacy.”

— Raoul Peck addressing Ernest Cole, “An Idea of Exile,” The True America

Ernest Cole’s story is as inspiring as it is tragic. A new film by acclaimed filmmaker Raoul Peck, Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, seeks to reveal more about Cole’s life, particularly the time between his exile from South Africa and his death from pancreatic cancer at age 49 in 1990. One of the first Black freelance photographers in South Africa, Cole exposed the abject brutality of life under apartheid — not as an outsider, but as a person actively resisting the same oppressive structures he was documenting. His exile to the United States in the late 1960s presented different challenges and opportunities, but revealed racism and segregation uncannily similar to the home he left behind. Despite publishing a monumental book that shocked the world, and garnering considerable fame himself, Cole and much of his work essentially disappeared in the intervening decades.

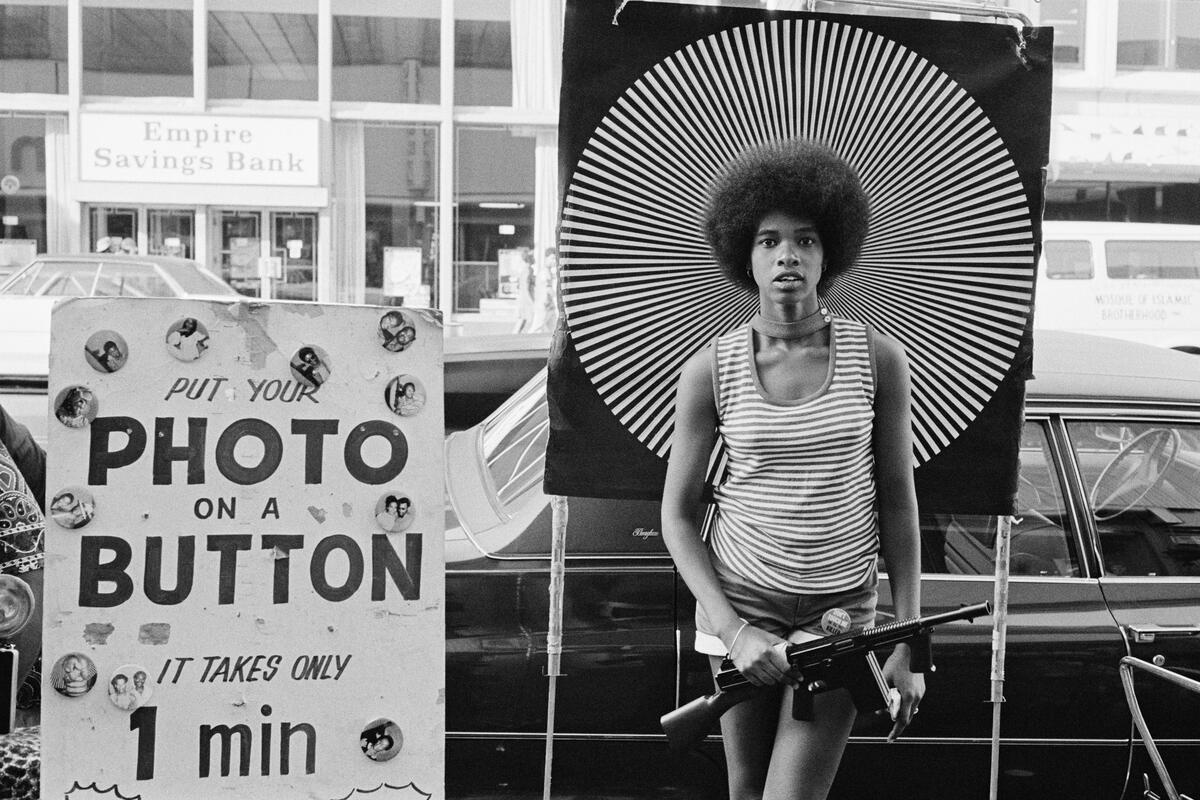

In 2017, over 60,000 of his 35 mm negatives were discovered in a Swedish bank safe in Stockholm and returned to the Ernest Cole Family Trust. How they got there and who paid to store them for more than 40 years remains unknown and many questions about the collection are still open. Earlier this year, Aperture released a book titled The True America, featuring many of Cole’s images taken in North America between late 1967 and early 1972, along with a preface written Peck, whose new film arrives on the heels of the book.

On May 20, Ernest Cole: Lost and Found premiered in the Special Screenings section at the 77th annual Cannes Film Festival and was bestowed the L’Oeil d’or prize — the award for best documentary. This, the latest feature-length documentary from Peck, marks his third appearance at the festival.

Peck’s filmography includes narrative and documentary work tackling social, political and historical subjects, including I Am Not Your Negro, Lumumba, The Young Karl Marx, and Silver Dollar Road, as well as a four-part HBO documentary series called Exterminate All the Brutes. The new film chronicles Ernest Cole’s life and work through his own words, thoughts, and images — reintroducing a pivotal Black photographer to a whole new generation.

“It was important for me to understand why Ernest, a well-known Black photographer from South Africa, sort of disappeared,” Peck said in relation to the film. “I was angry each time I read that Ernest was depressed, that he became homeless, or that he had paranoia. They didn’t see him as a human being or respect him as an artist who was going through something. So I read all that and thought, ‘I know that nobody becomes homeless just because they are lazy, or because they are crazy.’ So it was important to me to really understand how he got there and give a human explanation to that black box.”

Peck’s relationship with Cole’s story and work started before he ever saw a photograph. Though Cole was older, they belonged to the same generation. Born in Haiti and forced to flee the Duvalier dictatorship with his family when he was a child, Peck knows what it is to be in exile and how to portray the homesickness, alienation, and sense of displacement that Cole was going through. “Getting in Ernest Cole’s skin was not hard because I knew that sensation of feeling that you’re not at home, that you don’t belong. I had it all my life. And the depression he went through, too. I knew what it meant not to have a room at some point.”

The filmmaker’s projects often deal with the horrors and global impact of settler colonialism, capitalism, and white supremacy. Peck, who was born in 1953, grew up with the anti-apartheid struggle. At 17 he was living in Berlin where many people engaged in the fight were in exile, including the ANC (African National Congress). Various liberation movements were in exile too and they demonstrated together. “I helped write a pamphlet and did photography at the time. So this is not a foreign story to me. On the contrary, it was something I could totally relate to.”

"It was important that I showed that reality. That's also why I start the movie with the Sharpeville massacre. People forget it. They think apartheid is just a figure of speech. No, people were dying. People lived their whole life under constraints, like prisoners of their own country."

- Raoul Peck

Filmgoers familiar with Cole’s 1967 book House of Bondage, published when he was just 27 years old, will recognize quotations, photos, and organization from the book early on in the movie. House of Bondage was the only book Cole published during his lifetime, but was re-released by Aperture in 2022 with an additional chapter. The book, lauded as one of the most important photobooks of the 20th century, was a thorough denunciation of apartheid and had global impact upon release.

South Africa unsurprisingly banned the publication and stripped Cole’s passport, forcing him to flee and live in exile for the rest of his life. Of course, eliminating, displacing, and censoring people who document atrocities, while propagating nationalist narratives through expensive public relations campaigns, has long been a specialty of despotic regimes. And today is no different. The past year has been one of the deadliest in recent memory for journalists and photographers covering state-sanctioned violence, particularly in Gaza. In this context, the work of Ernest Cole, and the film itself, compels viewers to confront and grapple with the barbarity of powerful nations — past, present, and future.

"Challenge institutions who have been the gatekeepers and the so-called saviors of all their work. They need to be questioned. You know, there is a great movement right now to return all the goods to their original countries. For me, this film is embedded in that movement. "

- Raoul Peck

With Cole as narrator, the film allows him to respond to the mostly white journalists, historians, colleagues, and critics who have opined on his work and impacted its wider reception — leading to often unintentionally patronizing narratives about the people and subject matter of his photographs. This deconstruction of one-sided or biased narratives is often present in Peck’s filmography.

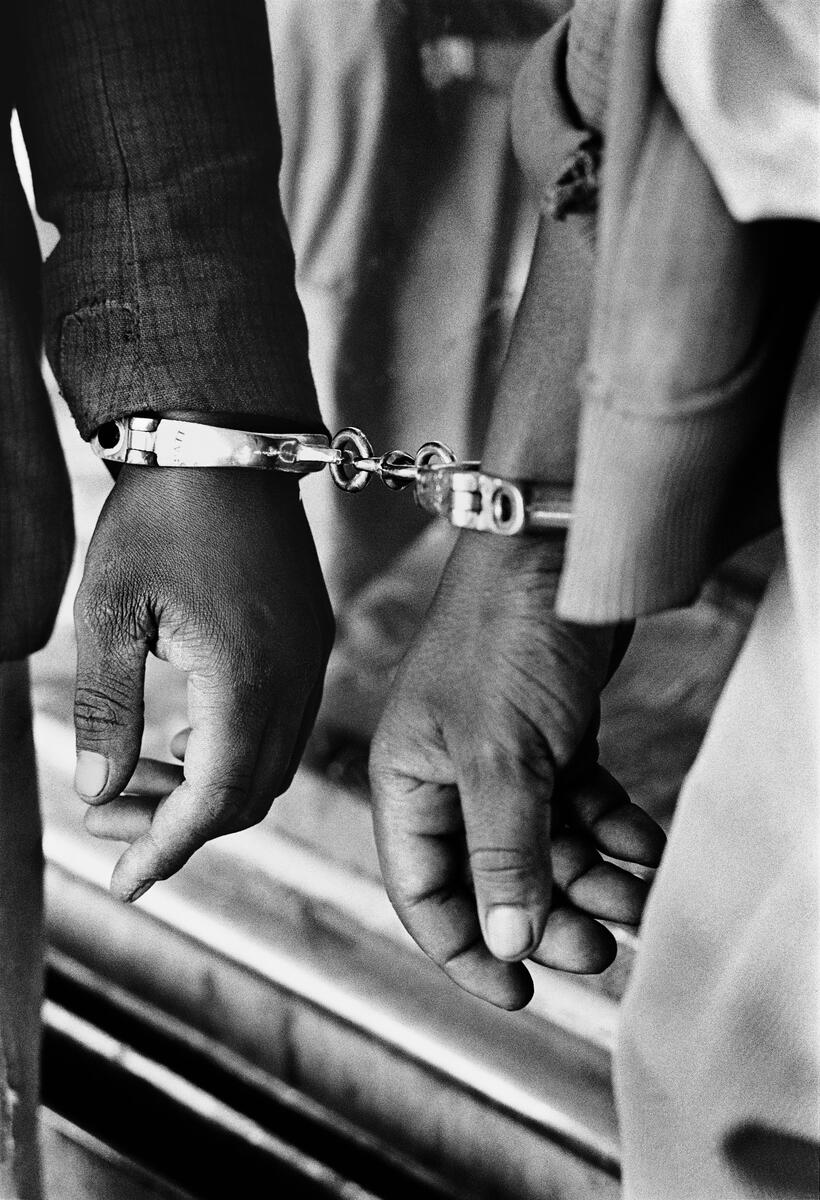

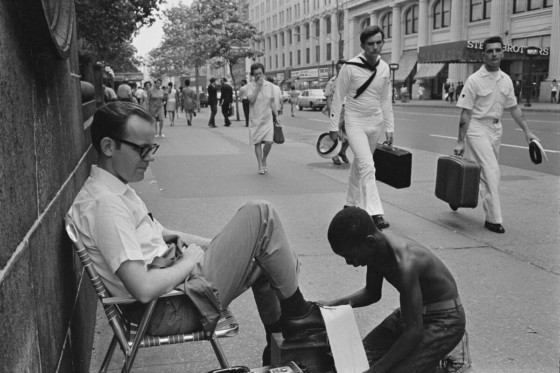

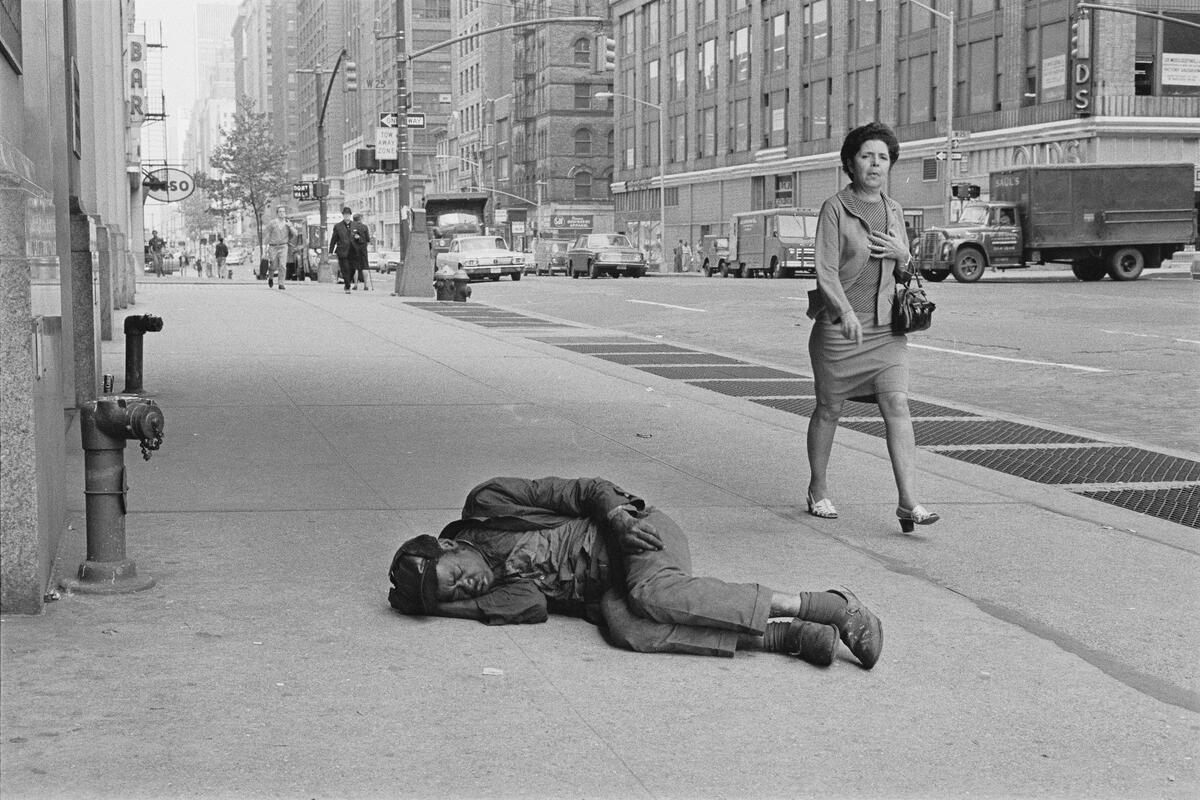

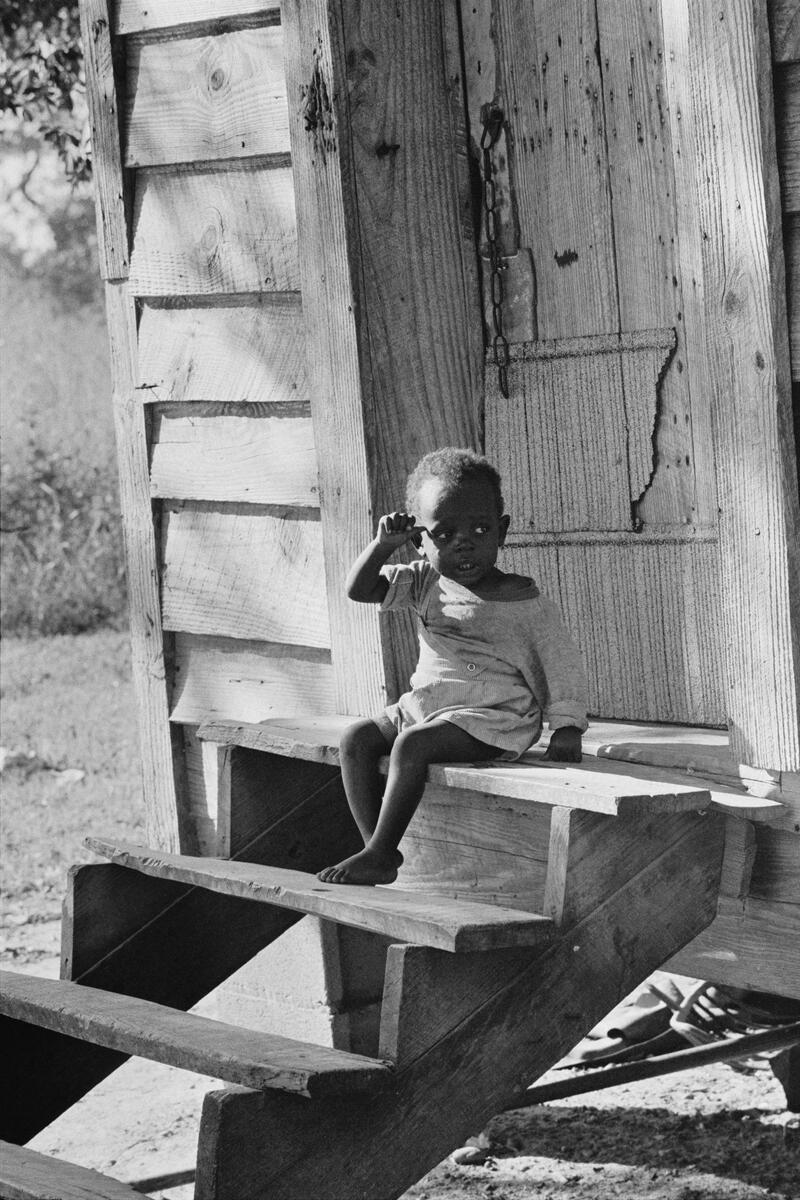

An example of the way Cole’s post-1966 work has been sidelined pertains to his photographs of the US South which powerfully and accurately drew parallels between Jim Crow and apartheid in a way that others could not and had not. Yet, the images were dismissed by colleagues at the time as “having no edge.”

Fortunately, Cole speaks for himself in this documentary and his perspective remains prominent the entire time. Through his images, text, and audio from the expanded archive, as well as the recollections of people closest to him, the story is being told directly. In the film, the photographer is voiced by LaKeith Stanfield, the Oscar-nominated actor known for films like Judas and the Black Messiah, Get Out, and Sorry to Bother You, as well as the show Atlanta. His delivery is as calm and sorrowful as it is resilient and impassioned, bringing emotional nuance and a deep humanity to the performance and the photographic work.

“I wasn’t going to tell this story through talking heads — that would have been a totally different story, like a biography,” said Peck in an interview. “And I don’t do biography, I tell stories. I want you to be able to watch this film twice, get into the story and be caught by it. That means you need characters, you need motivation, conflict, evolution, redemption, all of that. And because I write screenplays, I know how to attain that, both in narrative and documentary form. And so the most important decision here was that he tells the story.”

“He has done theater, and he’s a very mature person,” Peck says about Stanfield. “He’s very grounded and he has a persona. And I love his voice, a very nonlinear voice. There is crackle in it. He’s sensitive and sensible. He told me that he had been photographing the last four years. He bought cameras and he’s really into it. So there was a lot of connection. And he really went through a journey throughout the film.”

Commenting on the film, its director, and the photographer he portrays, Stanfield said, “I have long admired the peerless Raoul Peck’s singular body of work. I’m honored to have the opportunity to collaborate with him on ensuring Ernest Cole’s essential story is heard.”

This isn’t the first time Peck has cast a leading actor to voice the protagonist of a documentary. Peck tapped Samuel L. Jackson for I Am Not Your Negro, his Oscar-nominated 2016 film about the writer and activist James Baldwin. For that project, Peck was granted access to the entire Baldwin archive, centering the film around an unfinished book titled Remember this House about Baldwin’s personal relationships with his deceased friends: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.

"The history of the world is, there is a long hundred years where as a Black person, you didn't have access to write your own story. This is a fact. I cannot change it, but it's still my history. So my job is to go and find those traces. And when I find them, I have to deconstruct them. So I would never make a film that is only about the past. "

- Raoul Peck

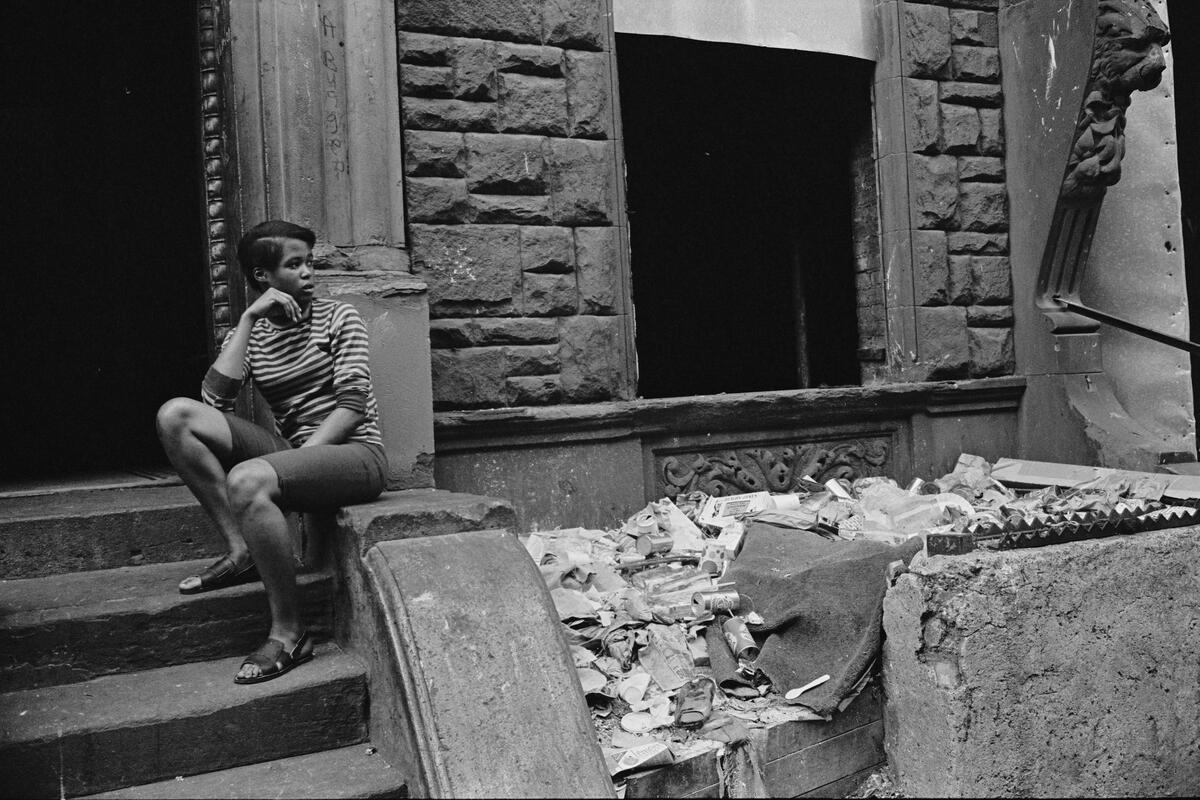

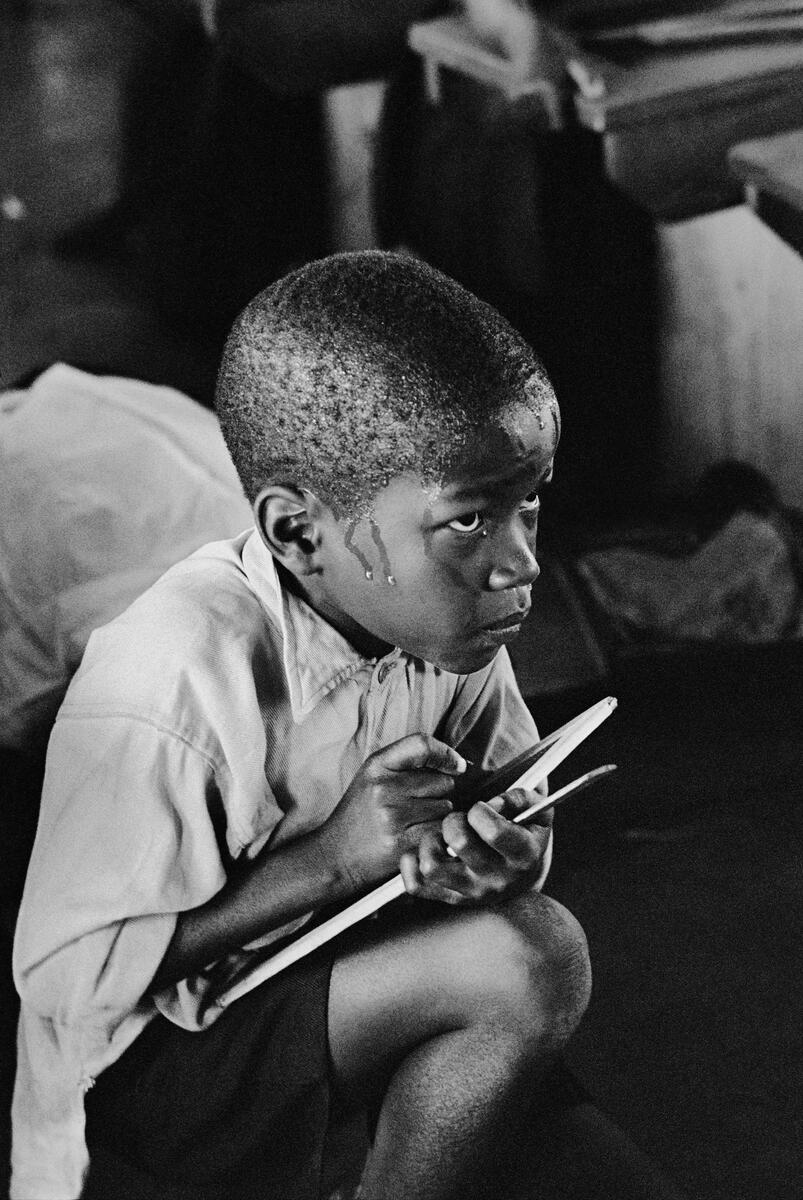

Work began on Ernest Cole: Lost and Found when the late photographer’s family reached out to Peck about the vast collection of negatives found in the bank vault in Sweden. Under-appreciated during his lifetime and largely forgotten until the 2017 discovery, many of the images feature Black Americans in New York and across the southern United States. He captured pervasive discrimination and structural inequality through scenes that frequently mirrored the conditions of South Africa. “Whites only” signs, living and working conditions, as well as the actions and targets of law enforcement sometimes feel indistinguishable between the two countries.

While much of what Cole found in the US hit too close to home, there were significant differences that fascinated him as well, especially early on. For instance, intimacy and self-expression were being shown openly in a way that they couldn’t be at home. Happy interracial and queer couples together in public populated several of his frames, though more widespread public acceptance was still decades away. An image of a kiss at a subway station between two men is one of the more tender in the film and in Cole’s oeuvre. For all of the pain and struggle felt and depicted, both under apartheid and in the US, he did find some moments of joy, curiosity, and community. Though whatever respite or solace he might have found was short-lived, if not entirely overshadowed.

In his preface to The True America, Peck writes, “On the contrary, it seems that most damaging for him, was the discovery that even in the most cosmopolitan city in the world, in a country that prides itself on being the bedrock of democracy and does not shy away from lecturing the rest of the world, there was misery, racism, ignorance, and solitude, regardless of one’s success or fame.”

After spending some time in the US, Cole said, “When I left home I thought I would focus my talents on other aspects of life which I assumed would be more hopeful and some joy to do. However, what I have seen in this country over the past two years has proved me wrong. Recording the truth at whatever cost is one thing but finding one having to live a lifetime of being the chronicler of misery and injustice and callousness is another.”

The film is scheduled for distribution by Magnolia in the US and Condor in France later this year.

The exhibition “Ernest Cole: House of Bondage,” curated by Anne-Marie Beckmann and Andrea Holzherr and adapted for The Photographers’ Gallery by Karen McQuaid, Senior Curator, opens at The Photographers’ Gallery in London on June 14, 2024.

The exhibition “Ernest Cole: A Lens in Exile,” curated by Mark Sealy, opens at Autograph in London on June 13, 2024

The books House of Bondage and The True America are available here.