Ernst Haas’ Early Color Images of New York

In an extract from the book ‘Ernst Haas: Letters & Stories,’ Inge Bondi tells the story behind the photographer's first color assignment in New York in the early 1950s.

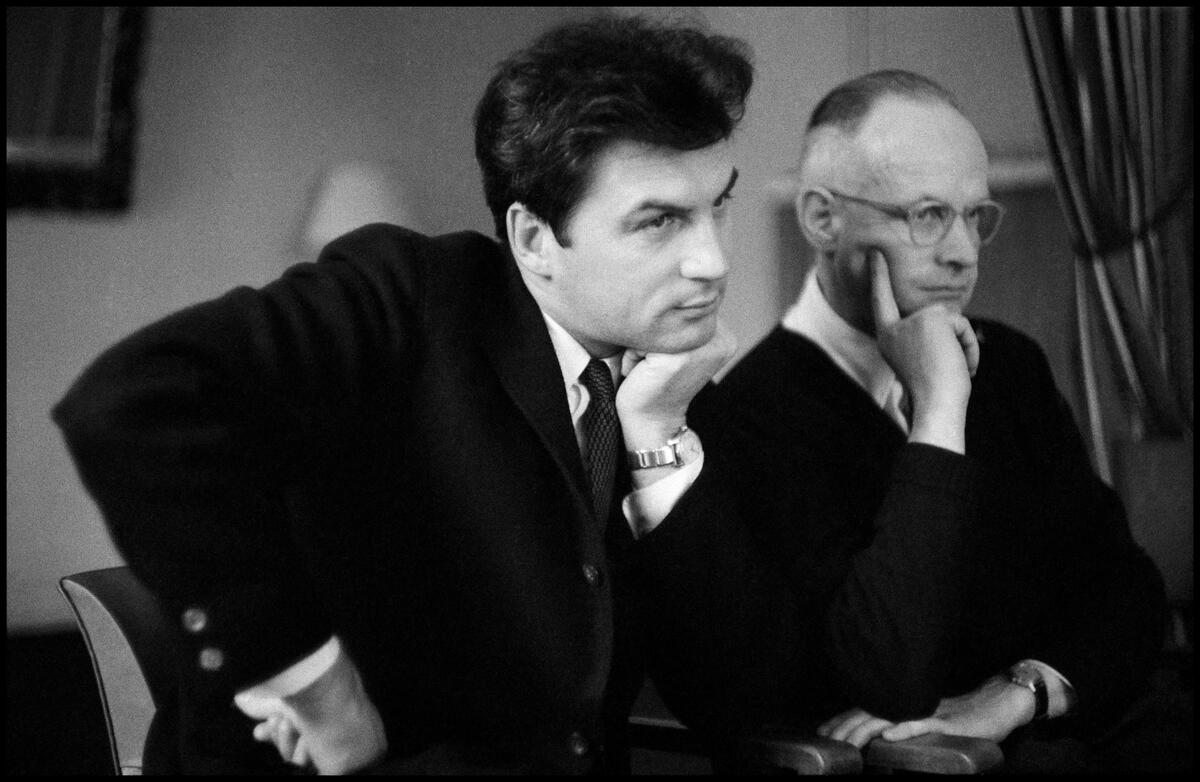

Inge Bondi first met Ernst Haas in May 1951 at the Magnum office in New York. At the time, she was one of the only two Magnum staff members in the office, and quickly befriended the fellow German-speaking Haas, who had just been appointed vice president of the cooperative’s American operations. The two Europeans, Bondi from Germany and Haas from Austria, worked closely together for over 20 years whilst they were both at Magnum, developing an irrefutable bond. When Bondi left to become an author and educator in photography, Haas helped her find her very first writing assignment, titled “Ernst Haas, Creative Force in Contemporary Color,” published in the July 1969 issue of Modern Photography.

Today, the subject of her first writing assignment is now the subject of her latest book, Ernst Haas: Letters & Stories, published in fall 2023 by Damiani. Looking back at his life and practice through a plethora of letters, poems, photographs, and dear memories, Bondi has pieced together the life of the master photographer, from his birth in 1921 right through to his passing in 1986. It is a tribute to both man and photographer — a glimpse into his personality, philosophy, and photographic practice, as well as into the legacy that he has left behind.

To celebrate the publication of the book, below we share an extract from its eighth chapter, ‘Pioneering In Color,’ in which Bondi recounts the story behind Haas’ first color assignment in New York in the early 1950s. When his initial idea of shooting the Grand Canyon in color was rejected by the editors at Life, Haas began to experiment with shooting in color in the city instead. Bondi writes of the success of his initial assignment, and how his unique vision set his photographs apart from any others that had been made of the city.

Chapter 8: Pioneering In Color

After two months of work, Ernst presented his story to Life in a projection of 130 photographs. The magazine published “Magic Images of a City” over 24 pages, in two successive installments. Since it was the baseball season, the cover featured Casey Stengel, the beloved baseball star, but below his picture, in large print, were the words: Color Photos Make Great City Into A New And Magic World. By tying the smiling baseball star to the New York feature, Life seemed to be saying, this is everyone’s city, just as Stengel is everyone’s hero. A full-page advertisement in the New York Times compared Ernst’s story with the work of such popular American writers as O’Henry and Damon Runyon, and songwriters Rodgers and Hart. The text read: “But this week there is a new New York seen through the camera eye of a young Austrian photographer, Ernst Haas. This is a magic city you look at every day, but now imaged in strange and wonderful ways. It is in color in this week’s Life, and next week’s too.”

Life continued with endorsements from the Mayor and other notables.

What had Ernst done to cause such a wondrous fuss? New York had been endlessly photographed and painted. Something new was needed. The landmark skyscrapers with their vertical lines presented a problem, but Ernst came up with an inventive solution. With the buildings so close to each other, constructed with so much glass, Ernst recognized what everyone saw, but no one had noticed: how the light reflected the buildings into each other: a phenomenon then unique to New York. Reflections became his subject, a key part of the story.

There was more. He photographed landmarks as New Yorkers saw them every day, but differently. The lead picture is the Brooklyn Bridge at dusk, from the viewpoint of the thousands of motorists on the East River Drive, with the sun setting at the close of the day. There is no Statue of Liberty, because Ernst saw his story as one for locals, not new immigrants or tourists. Instead of the Empire State Building, he photographed skyscrapers in the evening haze, a backdrop to children swinging in a playground. There are little marks of humor: telescopes with their metal faces seeming to look out for would-be viewers or a squirrel sniffing at a chalk drawing on the pavement. There is a gaudy reflection of traffic in Times Square windows with a stuffed turkey and oncoming cars. There is the famed Hotel Pierre at cocktail hour, a golden building reflected upside-down in a lake in Central Park.

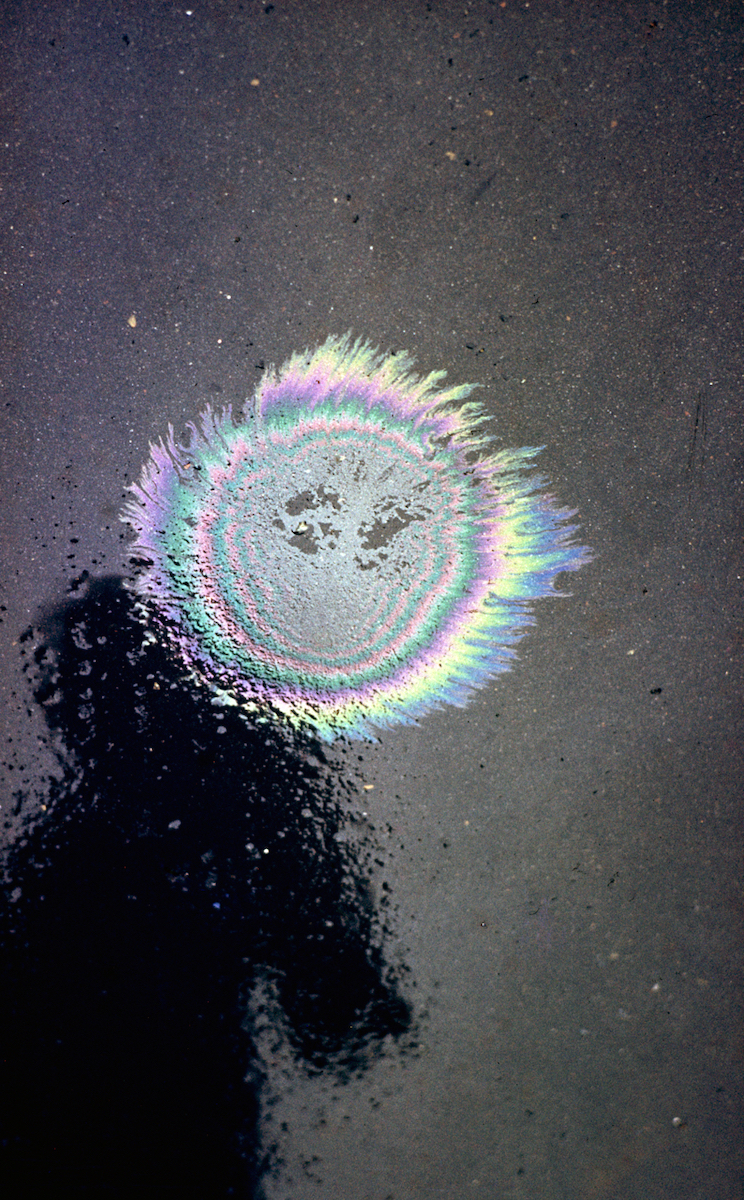

Ernst caught reflections all over the city, at different times of day, with light a crucial factor, introducing subtle hues and silhouettes into a world of primary colors. He captured still lives that spoke of people. Life described his image of an oil spot in the road as showing “a splash of oil in a pavement that creates a halo to glorify the shadow of a pedestrian hurrying by;” against a “sunburst of color, a Broadway sign painter prepared his paints for the work of the day.” He included the city’s mess, in the heap of junked cars seen from neighboring New Jersey, a picture of waste not encountered in Europe. In this vibrant new world, he photographed a silhouette of two chimney pots as a symbol of a couple looking into the sunset. This was his impression of New Yorkers in love. Decades later, Tonus [Haas’ first wife] described him at work on the story:

Capa told me once that it was Ernst’s eyes that made him a good photographer but I believe it was his whole personality, his education, his culture, his philosophy of life, his great knowledge and understanding that made him see people and things in a different way. Nothing was too small to capture for posterity: some happening, modest as it may have seemed at the time, or an image that struck his fantasy, like a dead pigeon, a fallen leaf, and an oil spot.

He was so alert, no shape, color or sudden gesture escaped his attention. He would always look in the right direction at the right time. He could feel something happening behind him and turn at such a speed, capturing the most important moment. He never offended people’s privacy and at times became invisible, so discreet was his approach.

He loved symbols and to interpret them was a great joy, like the New York chimneys against the setting sun. They were to him man and woman in a Smith-like sculpture.

Pictures came out of his very being. Even without a camera he was framing pictures with his fingers. He said himself he was not always conscious of why he took a certain shot, but he always knew afterwards and proved to be right.

That he wanted to do the New York story was obvious from the start, even if he did not know what shape or form it would take. The story was in him.

Find out more about Ernst Haas: Letters & Stories, published by Damiani, here.

Signed copies are now available in the Magnum Online Bookshop.

Text by Inge Bondi

Research and Writing Associate: Rixt A. Bosma

Editor: Helen Rogan

Producer: Susan Meiselas

Assistant Producer: Sumeja Tulic