Florals: Through Magnum Images

Clothes worn in this cheerful print assert the wearer's femininity and symbolize major life stages

In the tenth installment of her series delving into Magnum’s collection of images, exploring its decades of documentation of vernacular style around the world, fashion writer Rosalind Jana here turns her attention to the floral print. Jana has previously reflected on topics including the symbolism and allure of high heels, the evolution of denim, and the luxury and utility of gloves. You can explore the full series here.

In Anne Stevenson’s poem ‘Granny Scarecrow’ memory becomes physical. After a funeral a dead grandmother is reanimated for a final time: “they crucified her old flowered print housedress/ live, on a pole.” Outfitted in florals and “white Sunday gloves,” this flapping figure nods benevolently at her two grandchildren who pass by daily on their way to school. However, time – and specifically winter – is not kind to this new scarecrow: “her ghost thinned./ The dress began to look starved in its field of snowcorn.” As the dress fades and the gloves develop mildew, the girls take another route to avoid it. Over the next ten lines they swiftly grow up, move away, make lives, have “children and grandchildren” and die themselves: “though, with the farm sold, none found a cross to fit their clothes.”

Stevenson tells a compact story in five stanzas. One that addresses loss, legacy and the cyclical nature of life and death with a remarkable ease. It is a poem that recognizes the scarecrow as a figure at once haunting and comic: just human enough to deter birds, flapping in the breeze, but somewhat eerie too. It also conjures the peculiar power of clothes, suggesting their role as intimate mementoes, or perhaps second skins, that hold traces of the owners who once wore them.

Given those preoccupations – the movement of time and season, the inevitable passage from childhood to old age – it’s fitting that Stevenson chose to dress this ghost of a grandma in a flowered print. After all, what could be more grandmotherly than a floral housecoat? Like sensible sandals or the smell of lipstick and face powder, it immediately evokes a world of simple, slightly dowdy dressing. Here, florals suggest soft armchairs and sturdy jute shopping bags. They conjure a whole image of a life from a passing mention of a print.

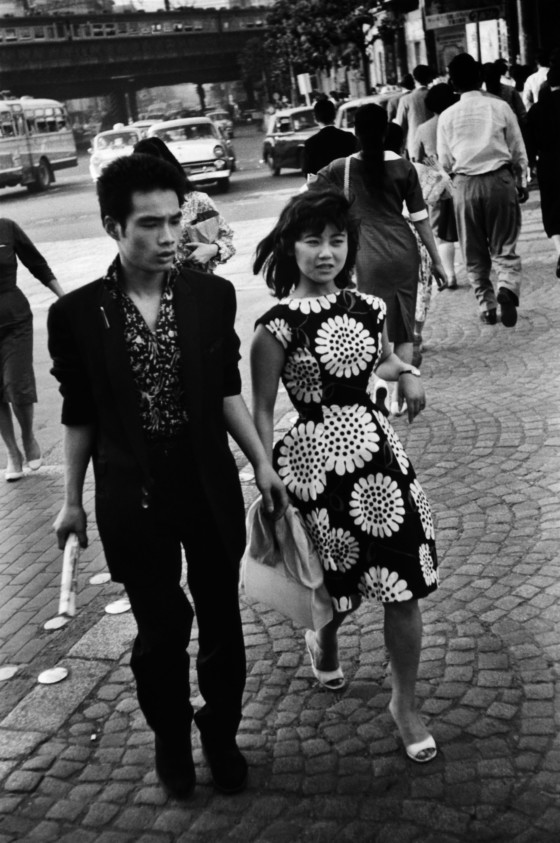

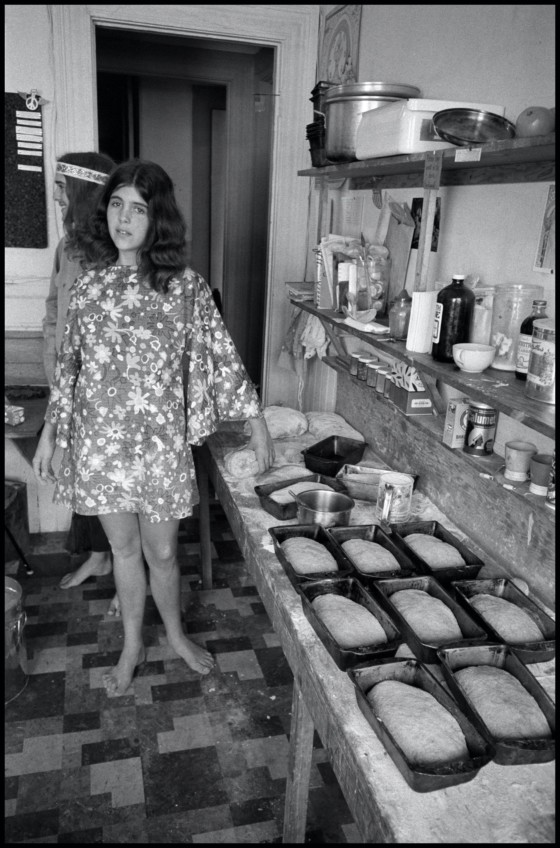

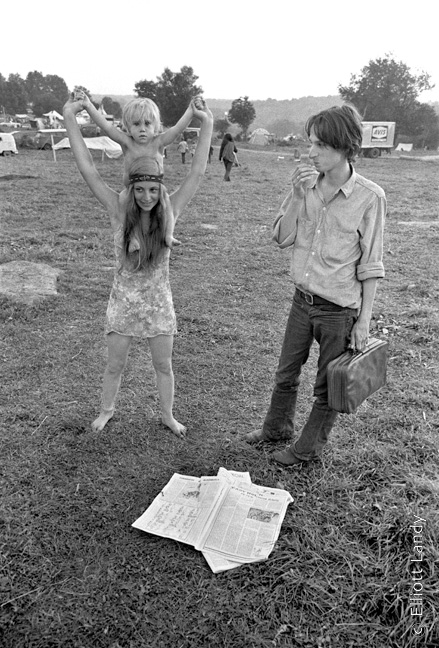

Florals are often evocative. Ubiquitous in their presence and varied in their effect, fabrics covered with flowers occur at many stages in life. Perhaps it is for this reason, as well as their alliance with particular historic periods, that their meaning feels so deeply linked to timing. Worn with white socks, they are read as the epitome of girlish childhood dressing – as found in Elliott Erwitt’s portrait from 1951. Scattered across a flowing frock, demonstrated in Bruce Davidson’s vivid shot for Vogue in 1962 or Elliott Landy’s flower power infused snap from Woodstock in 1969, they suggest the flourishing of youth. Gracing a sophisticated dress, a la Inge Morath’s 1950s beauty contest photos (the provenance of the clothes are unclear but the silhouettes are classic Dior – the designer once saying that he “drew women-flowers” with “fine waists like liana and wide skirts like corolla”), they indicate a desire for polished womanliness.

"Ubiquitous in their presence and varied in their effect, fabrics covered with flowers occur at many stages in life."

-

"Gracing a sophisticated dress ... they indicate a desire for polished womanliness.

"

-

Within Magnum’s archives, florals reoccur frequently on older people too – particularly women of a certain age (and a certain era). Women going shopping. Women eating scones with jam and cream. Women fetching water in tin pails. Women swathed in sunny yellow outside the Taj Mahal. Women cackling as they smoke cigars, decked out in bright blue and orange. Women with handbags dangling from the crook of an elbow. Women sunning themselves on park benches, as with Richard Kalvar’s beautiful photo taken in Washington Square Park in 1968: the subject’s face turned up towards the light, one hand outstretched in a silent motion of pleasure. For these women florals often seem to not only bely an assertion of femininity, but something robust and a little irreverent too. Their clothes are comfortable and cheery. They are not afraid of being loud.

Occasionally in these photos several prints end up clustered in the same frame, like a happily overflowing garden. Cornell Capa’s 1950 photo of two spectators at an archery match reveals one woman’s stylized daisies facing off against another’s sketched bouquet, both wearing elaborate hats trimmed with flowers and lace. In Bruno Barbey’s portrait of a group of villagers in Morocco, vibrant colours dominate the frame: white flowers flecked across red, vast blue and pink blooms billowing on skirts. In Martin Parr’s 1993 portrait of a group on a Hawaii beach, several floral shirts feature. Their shades range from palest, translucent pinks to flamboyant purples and greens worn with clashing yellow socks.

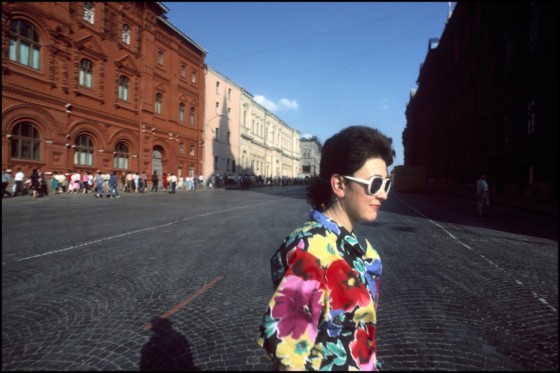

In nearly all instances, florals make us think of growth and life. Ever since humans began garlanding themselves with flowers before borrowing from the outdoors to embroider, weave and eventually print these natural forms onto fabric, we have found ourselves enchanted by their abundant potential. The sheer variety of what we can steal from mother nature helps too. The effect of a pink, sprigged blossom is very different to that of a blowsy cabbage rose or an elegant iris. A prim buttercup print on cotton differs hugely in both intent and effect to scarlet poppies rippling on silk. Some of the most joyful Magnum images featuring florals are also the boldest: women crossing the street in big, zany prints, girls in layers of flouncy netting embroidered with leaves and petals, figures lingering in front of paintings that echo back the shapes and shades of a flowering shirt.

Perhaps florals appeal too because of their seasonality. A winter flower can be very beautiful, but once bare legs and arms are possible their attraction heightens tenfold (one inevitably hears Miranda Priestley muttering “Florals? For spring? Groundbreaking” somewhere in the background.) Each year the arrival of life from dead earth feels like a blessing, or at the very least a reassurance. Time moves forward. Trees shed and regain their leaves. New things bud. Grey is once more replaced with colour.

For this reason there is always a certain nostalgia to this warming of the months. The artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman, who created a magnificent garden on the beachfront of Dungeness as an adult, recalled various moments of pastoral idyll in his memoir Modern Nature. There he wrote that “flowers spring up and entwine themselves like bindweed along the footpaths of my childhood.” Many of us have similarly adorned footpaths, our recollections overgrown with parks, gardens, and wild landscapes.

Floral prints often seem to reflect this understanding of both time and terrain. There is often an implicit comfort to them, invoking visions of bucolic innocence. Elsewhere they offer a sense of renewal and fecundity. But as Anne Stevenson’s poem demonstrates, like all forms of clothing, they are not immune from the cyclic inevitabilities of life either. Flowers grow, die, and return again. Florals acquire different meanings according to the age of the wearer. Sometimes they will outgrow their use, or eventually fade and grow tattered. But more will always spring up in their place: fresh blooms hanging on racks, embroidered on blouses, unfurling across ballgowns, waiting for a new wearer to take them out into the sunlight.