Housecoats, Bathrobes and Dressing Gowns: Through the Magnum Archive

Magnum images depict how house robes have variously signified glamour, intellectualism, seduction and liberated artistry throughout history

In the sixth installment of her series delving into the Magnum archive, exploring its decades of documentation of vernacular style around the world, fashion writer Rosalind Jana here focuses upon dressing gowns. Having previously reflected on the evolution of denim, the cultural highs and lows of leopard print, the revolutionary impact of nylon hose, the act of dressing up, and the luxury and utility of gloves, here Jana considers the cultural connotations of the dressing gown.

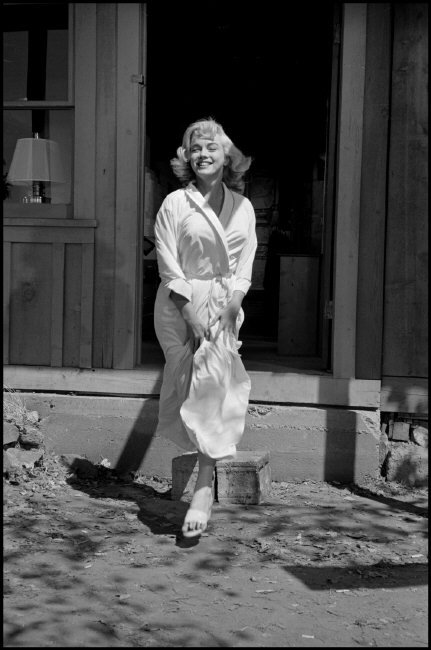

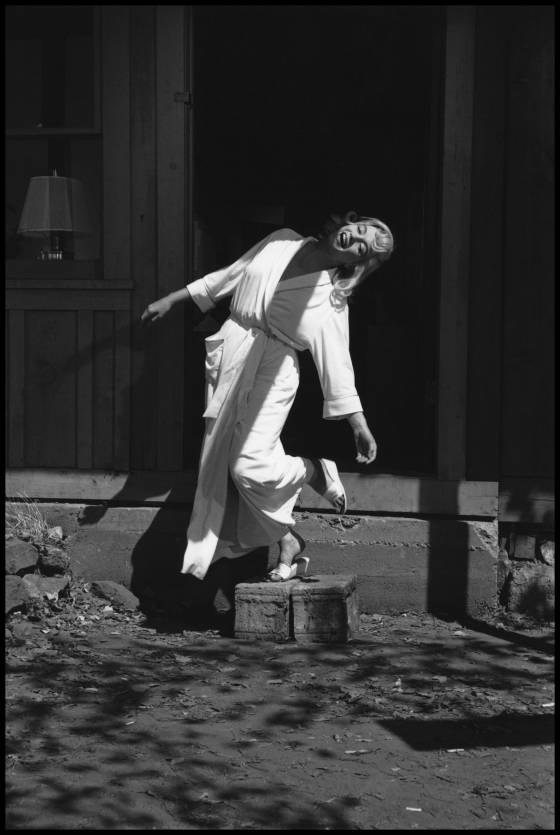

Marilyn Monroe suited many things: black polo-necks, ritzy cocktail gowns, billowing white dresses, pencil skirts, shirts knotted tightly at the waist. She also looked fantastic in a dressing gown. Or rather, a bathrobe – that soft white garment usually made from toweling or, at a push, cotton. The kind calling to mind the discreet luxury of fancy hotels, as well as Hollywood stars awaiting their next take.

Within the Magnum archives Monroe is pictured frequently in a bathrobe, captured by a range of photographers including Inge Morath, Eve Arnold, Dennis Stock, and Bob Henriques, They are images that stand apart from the neatly made-up, beautifully dressed Monroe at awards ceremonies or on film – capturing, instead, the intimacy of an actor at work as she checks over scripts or jokes with co-stars. It’s a useful kind of attire for an actor on set, ideal for hanging around in. Clean and comfortable, it is both highly functional (warm, easy to put on and take off, useful to avoid make-up stains on clothing) and elegantly evocative. On Monroe it takes on a kind of undone glamour – loosely tied as she drifts around, not quite dressed but perfectly respectable too.

"Clean and comfortable, it is both highly functional [...] and elegantly evocative"

-

On Monroe, as well as numerous other performers readying themselves for stage and screen, the bathrobe is part of the job, marking the transition from actor to costumed character. But it has other uses besides dressing celebrities. Also the standard uniform of spa-goers, it offers something more robust than the humble towel when drying off. A nod to cleanliness too. White is a good color when one wants the assurance of something pristine. In Ferdinando Scianna, Sim Chi Yin and Carolyn Drake’s portraits of bathers this pristine quality becomes intriguingly identikit, erasing individual identity as everyone walks around in duplicate robes.

If the bathrobe demarcates a between-space – between clothes, between characters, between water and changing room – then different forms of the dressing gown offer other sorts of informality. Really, it’s less a single item than it is a whole genus of similarly functioning but distinct garments. Historically they’ve been deemed everything from housecoats (more apron-adjacent, useful for domestic duties) to smoking jackets (shorter, often quilted).

"If the bathrobe demarcates a between-space – between clothes, between characters, between water and changing room – then different forms of the dressing gown offer other sorts of informality. "

-

In Japan there’s the yukata: a kind of light cotton kimono which originated as a bathing robe, and is now worn during traditional occasions and on the street in summer months. They are commonly worn whilst bathing at onsen – hot springs; here the yukata are worn by two hotel-goers in Kawaguchiko, pictured by Chris Steele-Perkins . In the 17th Century and 18th Century, there was the banyan: a garment initially worn by wealthy farm-owners in colonial territories in the form of a loose-fitting, T-shaped robe, which gained popularity in the West as a form of leisurewear among affluent intellectuals such as Benjamin Rush. With a name derived from the Gujarati word for a Hindu merchant or trader, a design often drawing on the kimono, and a series of fabric choices including Chinese silk and Indian chintz, it was a garment that epitomized the age’s obsession with a generalized ‘exoticism’ and the fruits of overseas trade. Rush said, “Loose dresses contribute to the easy and vigorous exercise of the faculties of the mind. This remark is so obvious, and so generally known, that we find studious men are always painted in gowns, when they are seated in their libraries.”

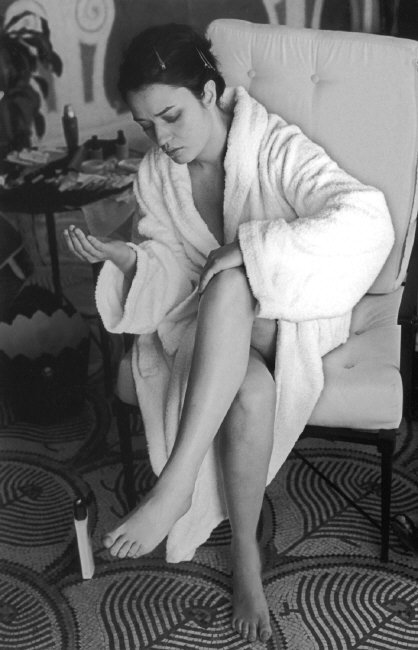

Even what we call a mere dressing gown today covers everything from a soothingly fluffy garment shrugged on over pyjamas to a louche satin or velvet number ideal for loafing around in, looking vaguely poised. The former, best identified as the most comforting type of dressing gown, is one we’re all familiar with. A good dressing gown should be an armour on difficult days and a source of warmth to ward off the chill. Offering the relief of something draped loosely around the body, it can envelop pregnant bellies, clad old men, and provide protection for all who wish to retreat from the outside world. In Elliott Erwitt’s 1953 portrait of a woman lying on a bed, hand to her head and slippers on her feet, we recognize the solace found in folding oneself up in something thick, soft, and unrestrictive.

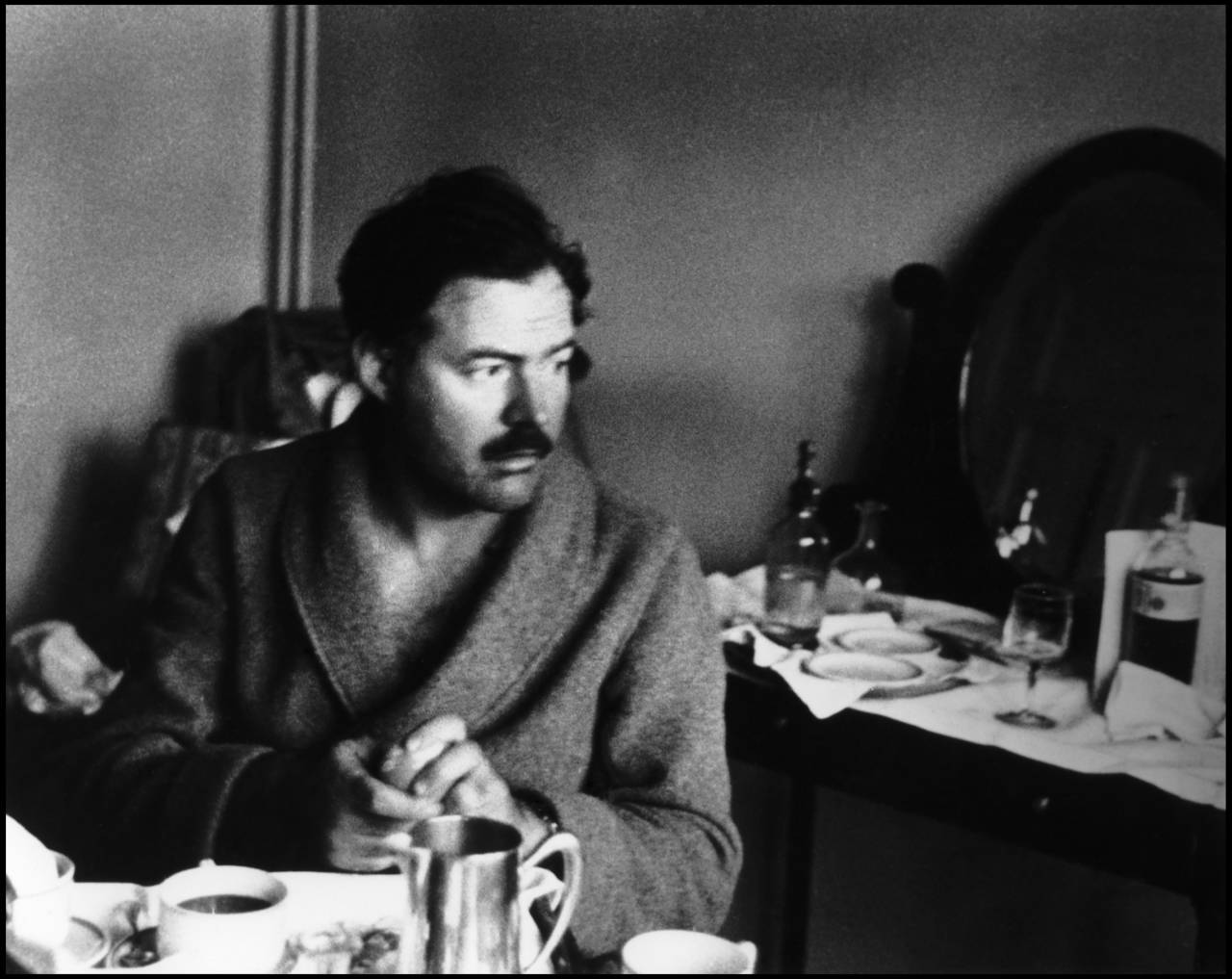

The latter type of dressing gown though suggests something a little more artful – the domain of authors at their typewriters and coffee drunk on sunny balconies.

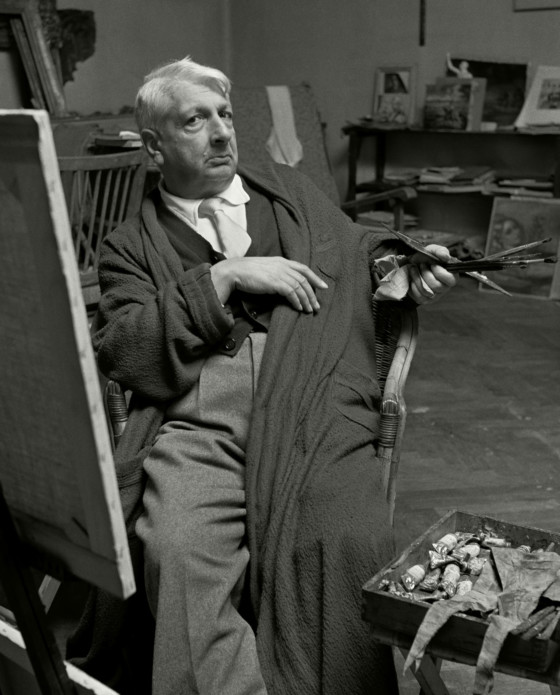

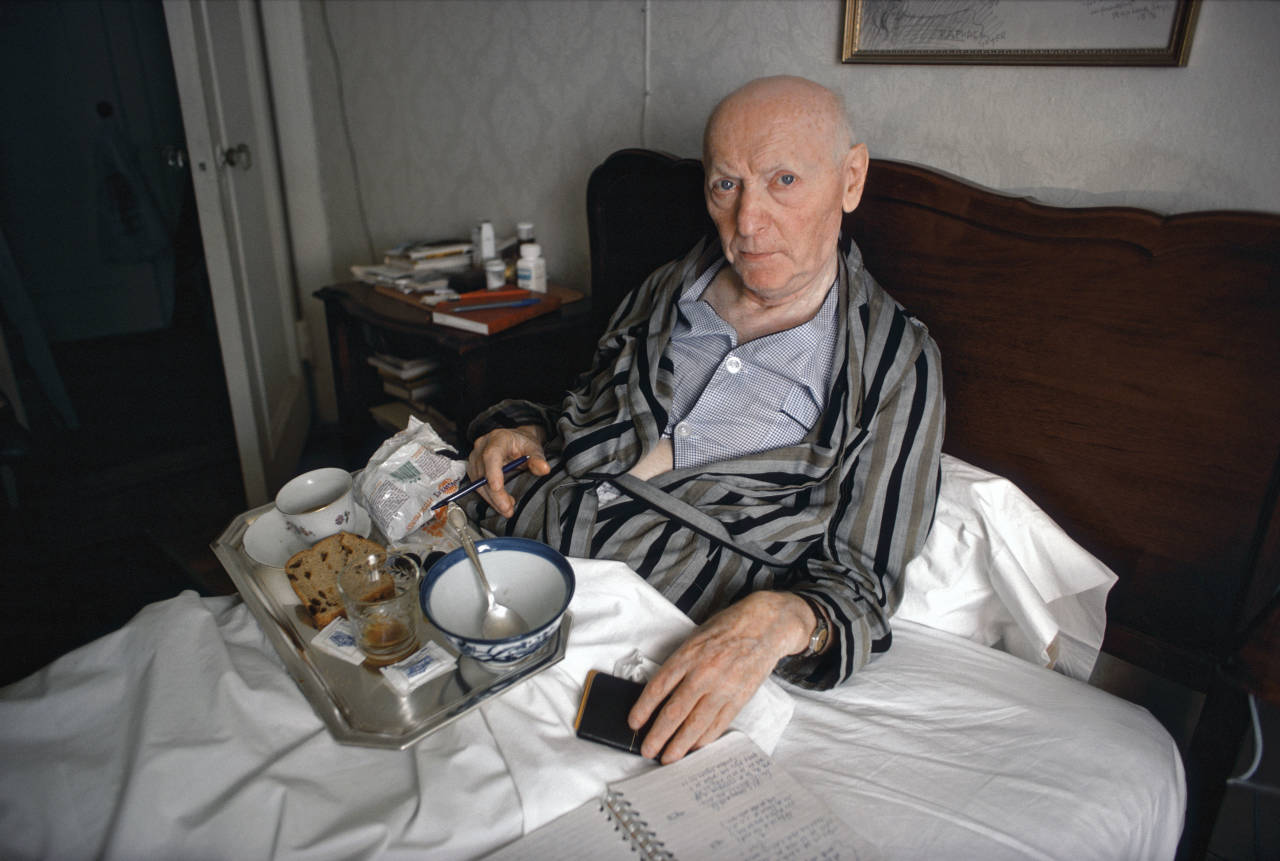

The Magnum archives yield Robert Capa’s portraits of Ernest Hemingway breakfasting in thick wool before heading to the front lines during the Spanish Civil War, as well as Herbert List’s photos of various literary and artistic luminaries including painter Giorgio de Chirico who wears a heavy housecoat in his studio; as does Jean Cocteau in another of List’s images. Then there’s Bruce Davidson’s 1975 portrait of Isaac Bashevis Singer, pictured here in pyjamas and stripes with a glimpse of stomach revealed beneath an open button.

"The latter type of dressing gown though suggests something a little more artful – the domain of authors at their typewriters and coffee drunk on sunny balconies."

-

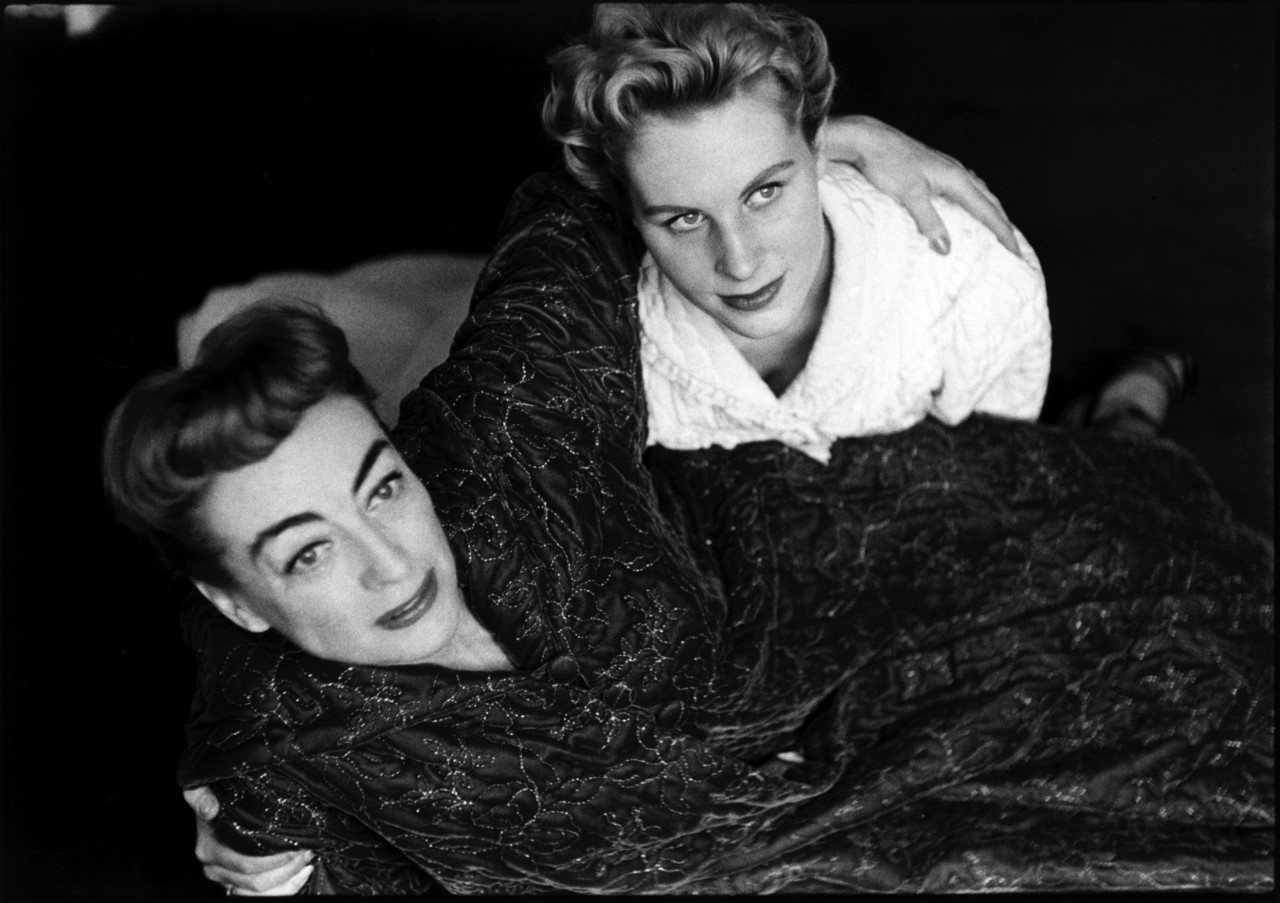

Some of these photos have a staged quality – see also Eve Arnold’s photos of Joan Crawford with her daughter Christina, deliberately informal but still pristinely done up – while others dangle the tantalizing promise of real, unvarnished insight. All are evocative, the viewer brought into close contact with someone still getting ready for the day, or perhaps, the day already in full swing, someone a little too unconventional (or creatively preoccupied) to immediately get dressed.

"This is the dressing gown as an item made to be seen and appreciated, providing yet another, more suggestive form of intimacy as it trades on texture and proximity to skin."

-

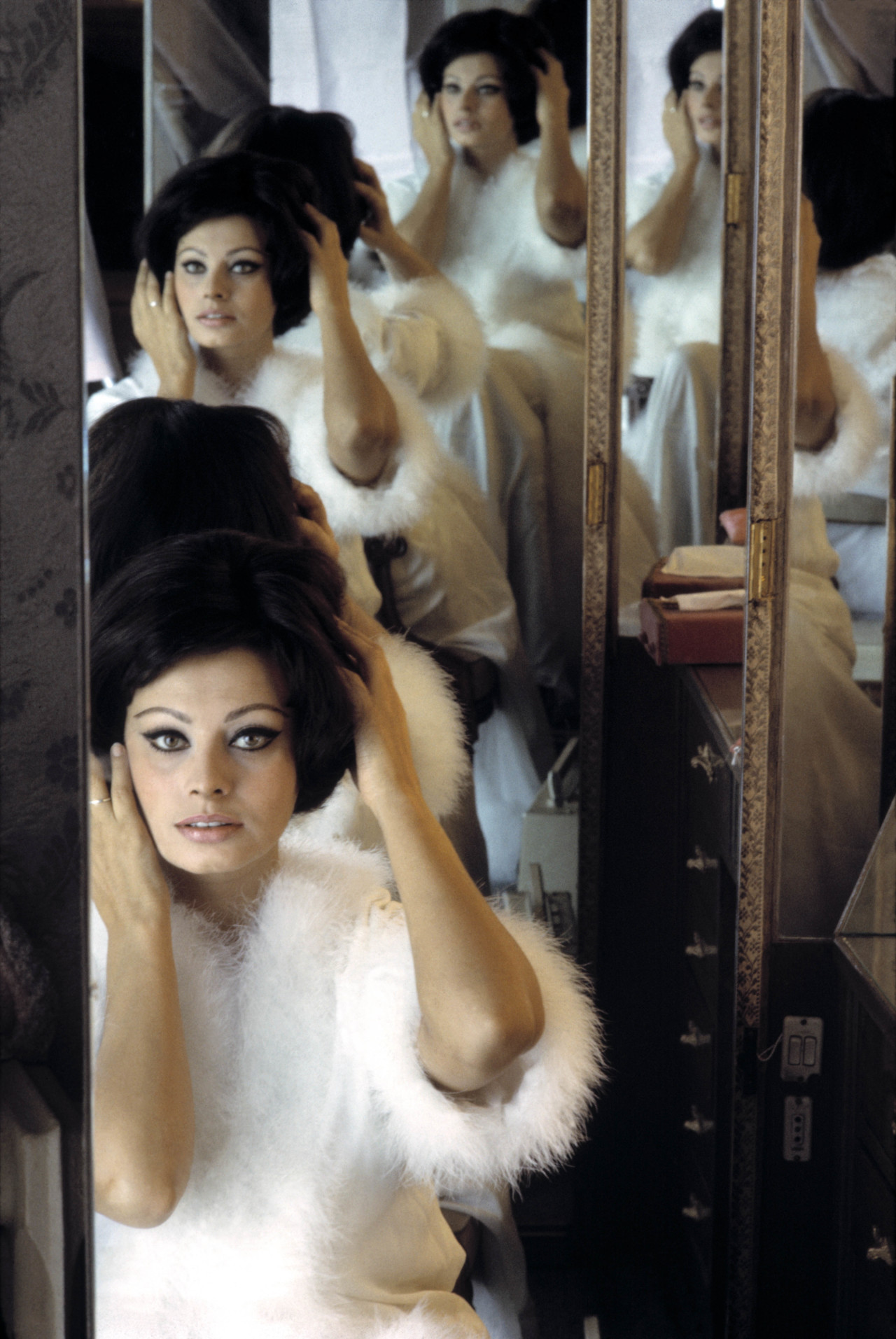

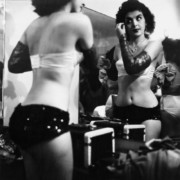

Then there’s the negligee. Usually see-through, the negligee and its cousin forms of flimsy nightwear pushes the dressing gown into the realm of the erotic – revealing as much as it conceals. Even when not translucent, it offers another kind of dressing gown trading in exaggerated glamour. Here we turn to Eve Arnold’s photo of Drusilla Beyfus in lace and puffed sleeves, Burt Glinn capturing an endless mirrored series of Sophia Loren, and Philippe Halsman’s portrait of Barbara Streisand in baby pink. This is the dressing gown as an item made to be seen and appreciated, providing yet another, more suggestive form of intimacy as it trades on texture and proximity to skin.

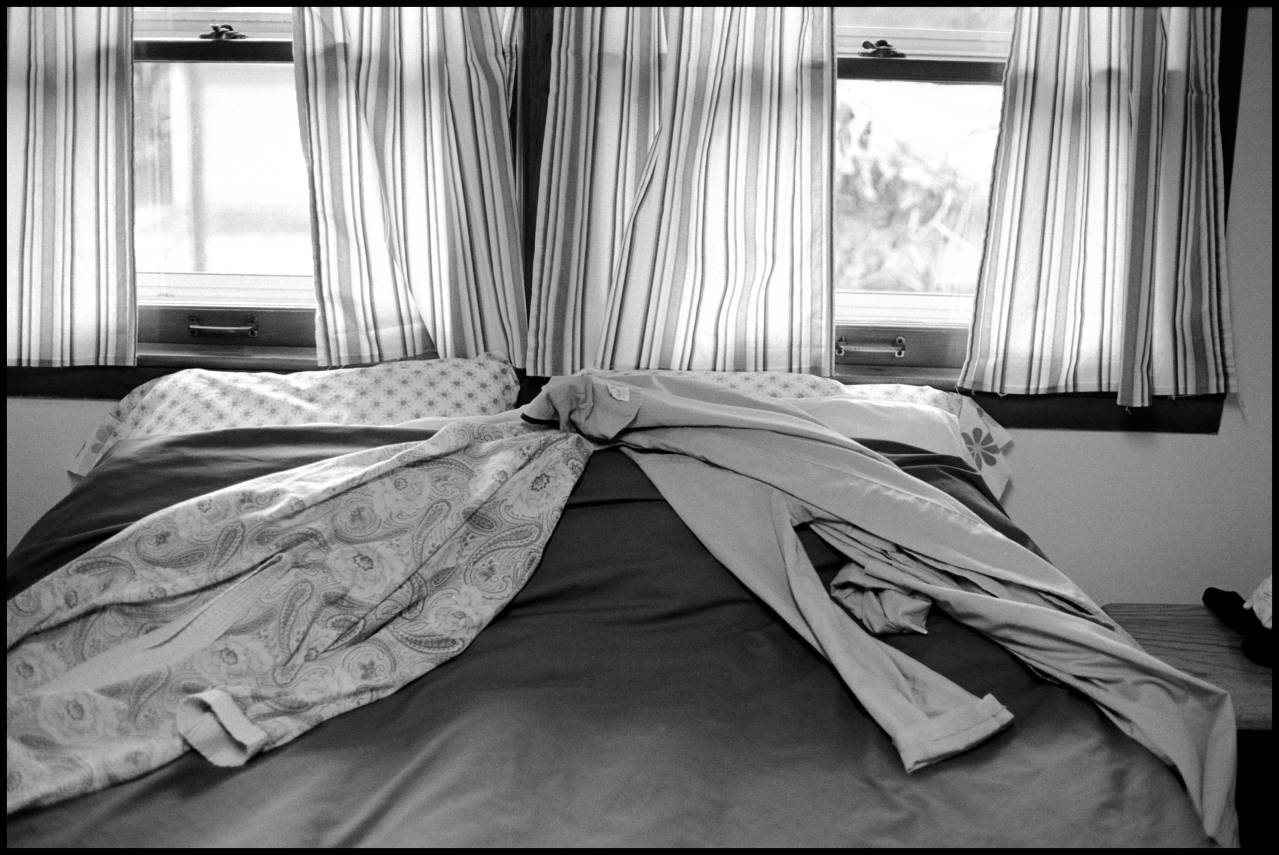

Of course, that’s what makes the dressing gown so interesting. It is nearly always an intimate garment, whether worn curled up in bed, flung over a jumper while writing, or cascading from one’s shoulders in a puff of nylon and marabou. The same can be said of its appearances in literature. In Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca, the titular character’s nightwear forms yet another reminder of a dead woman’s lingering, almost overpowering presence. The imperious housekeeper Mrs Danvers keeps her former mistress’s bedroom intact, cruelly entreating the newly married, young Mrs de Winter to hold up the satin dressing gown and compare herself to its former inhabitant: “she was much taller than you, you can see by the length… It comes down to your ankles.”

"...that’s what makes the dressing gown so interesting. It is nearly always an intimate garment, whether worn curled up in bed, flung over a jumper while writing, or cascading from one’s shoulders in a puff of nylon and marabou."

-

Elsewhere it is less of a memento mori and more a reminder of the body’s refusal to submit. In Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, the central protagonist – a brash, buxom trapeze artist named Fevvers who may or may not have actual wings – retreats to a “grubby dressing-gown, horribly caked with greasepaint round the neck” after her glittering performance. Jack Walser, a skeptical journalist interviewing her backstage, notes that her “notorious and much-debated wings” are “stowed away for the night under the soiled quilting of her baby-blue satin dressing gown.” This is another sort of intimacy – Fevvers sitting in her spoiled satin, playing a different kind of show as she spins elaborate stories far into the night.

The dressing gown, whether pristinely preserved or stained with greasepaint, is intimate precisely because it belongs backstage and in bedrooms. It is worn in the morning, at night, when ill, or somehow removed from the daily patterns of dressed life. It is a garment that comforts and charms, that can signify silk-clad elegance or read as an indicator of slovenliness – not an undone glamour, as with Monroe, so much as being merely undone. It is a garment that holds us close and gets hung up again before sleep. It suggests relaxation, rest, a pause behind the scenes, or the luxury of a slower pace of existence.

Beyond closed doors though, it remains notable. Take Bruno Barbey’s 1968 portrait of a dressing-gown-clad man and woman in Paris’s Latin Quarter. It’s a striking image precisely because they are both so out of place – wandering through the aftermath of a night of student riots and police attacks, their surroundings reduced to rubble. In their nightwear, the pair figure as yet another rupture in usual proceedings. Around the breakfast table they wouldn’t be anything special. But here they form a question mark: slippers too soft for the dust and debris beneath their feet, her quilting and his plaid wool setting them apart from passers-by wearing jackets. As they pause, she looking directly to camera, they embody some of the strangeness of a tumultuous time, indoor intimacies brought out into the open.