The Story of Style: Inge Morath

Fashion editor Justine Picardie delves into the fascinating story behind the iconic images by Inge Morath, defining mid-century fashion across England, France and America

A new book, ‘Inge Morath: On Style‘, edited by writer and curator John P. Jacob, documents the legendary photojournalist, offering deeper insight to her years of celebrated work. This text is taken from the introduction of the book, by British fashion editor, biographer, and journalist, Justine Picardie:

In 1998, Inge Morath was interviewed by the New York Times on the occasion of a retrospective commemorating her seventy-fifth birthday. During the interview Morath told a story about her life in Berlin during the Second World War, when, having refused to join the Hitler Youth, she was drafted to work in an airplane factory alongside Ukrainian prisoners of war. The forced labor brought her into constant danger, as the factory was a frequent target for Allied attacks. “Between the bombings,” said Morath, “someone once gave me a bouquet of lilacs and I held them up over my head and ran through the bombed-out city.”

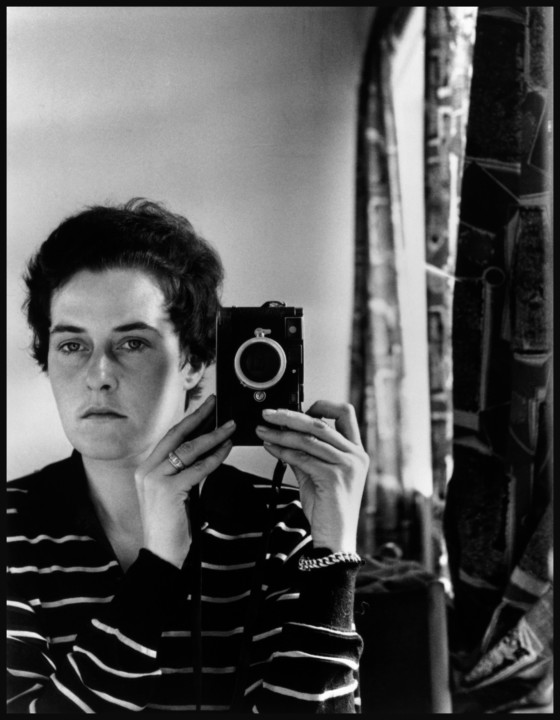

Though this memorable image was created in words rather than pictures, it might also be a clue to understanding the profound depth and subtlety of Morath’s photographs, even when she appears to be exploring the beautiful surfaces of style. For all her wit and light- ness of touch, there is often a sense of darkness beyond the edge of the frame. How could it be otherwise, given what she witnessed during the war?

Born in Austria in 1923, Ingeborg Morath was the child of liberal Protestants, both research scientists. The family was living in Germany at the outbreak of war, and the horror and suffering that Morath witnessed thereafter was to have a profound and enduring effect. In the same interview with the New York Times (conducted less than four years before her death), Morath offered another telling image of her wartime experience: “Everyone was dead or half dead. I walked by dead horses, by women with dead babies in their arms. I can’t photograph war for this reason.”

After the war, Morath’s linguistic expertise led to jobs as a translator and journalist in Munich and Vienna (she studied languages at university, and became fluent in French, English, and Romanian as well as her native German; to these, she later added Italian, Spanish, Russian, and Mandarin). By 1949, she was working with the young Austrian photojournalist Ernst Haas, and their talents were such that they attracted the attention of Robert Capa, the legendary war photographer and co-founder of the Magnum agency (established in 1947), who invited them to join him in Paris. Interviewed by Alex Kershaw for his biography of Capa, Morath recalled that she arrived in Paris on Bastille Day 1949, and went straight to the Magnum office on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. That night, Capa took Morath out to dinner, and suggested that she should acquire some stylish clothes; this she man- aged soon afterwards, when she met the Spanish couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga at a party. “I think he liked me because I was doing this dicey stuff, and he gave me a couple of suits, with pockets everywhere for cameras and film. They were so elegant–I still have one! Anyway…after that, Balenciaga made all my clothes for a long time.”

There are several different ways that one might interpret this story. It could be cited as evidence of sexism (a macho war photographer telling a brave young woman to dress in a more ladylike manner) or of practical necessity (a smart suit would allow Morath to make her way in the world). More likely is that Capa–born Endre Friedmann in Budapest in 1913–was possessed of an innate understanding of style, since his parents had been successful dress- makers. But what is also striking is the degree to which Morath must have charmed the famously shy Balenciaga, for he not only dressed her but subsequently allowed her to photograph him at home in 1959, at his country home, La Reinerie, near Paris. By this point, a decade after her arrival in Paris, she was a distinguished photographer in her own right, and had been recognized as such by Mag- num. (Having first joined the agency as a writer and researcher, assisting its co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson, she became a full member in 1955).

Unlike her mentor Capa–who died in 1954 after stepping on a land mine while on assignment in Vietnam–Morath continued to eschew war photography. But her courage and adventurous spirit was never in doubt; her many foreign assignments included a trip to Iran in the mid-fifties, where she travelled alone for most of the time, dressed in a traditional chador.

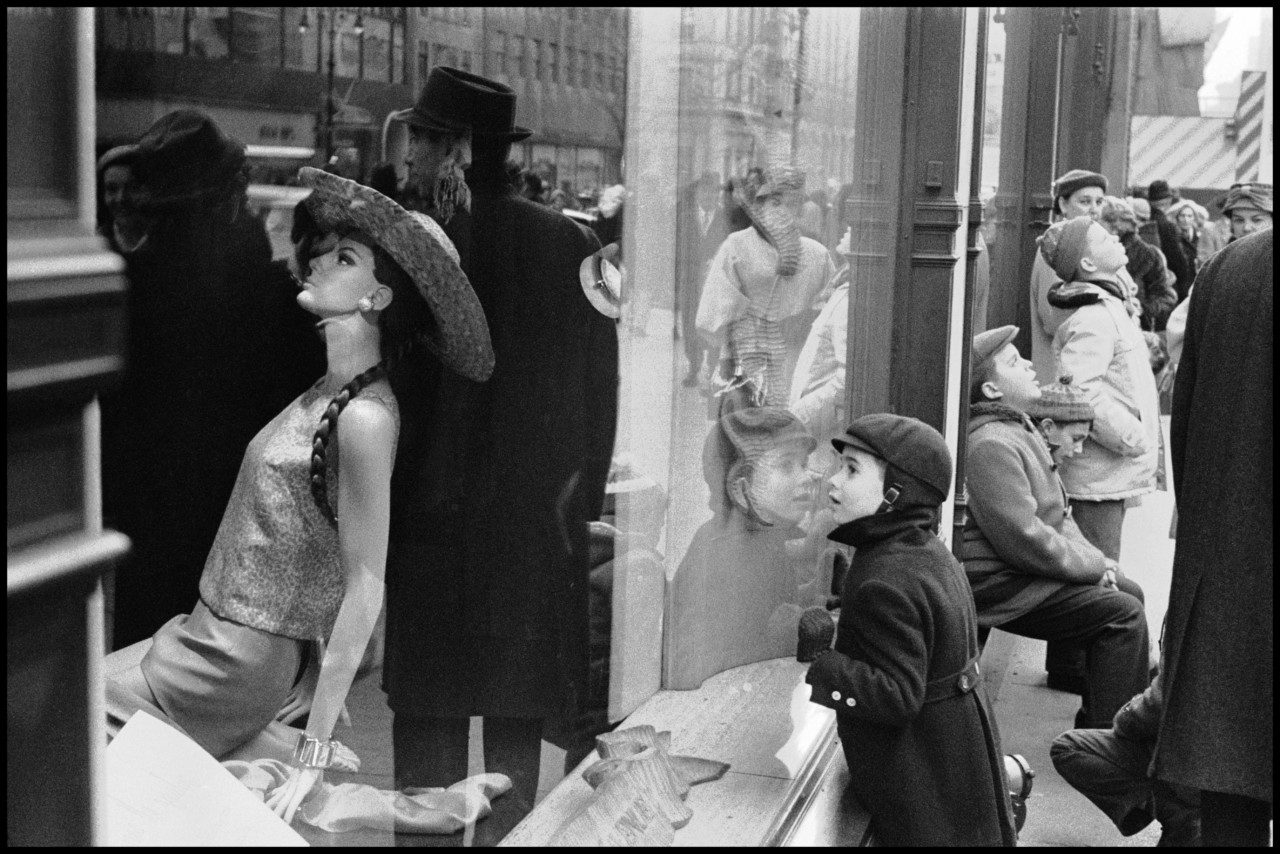

Morath was equally adept at discovering new stories in more familiar places. In 1951, she moved to London, where she started working for Picture Post and was briefly married to one of its journalists, and subsequent editor, Lionel Birch. (She was his sixth wife, and though the marriage lasted only briefly, Birch, undaunted, went on to marry for a seventh time.) Her atmospheric photographs of London in the early fifties are a glimpse into a lost world that was still clinging to the vestiges of tradition, such as the debutantes’ presentation at Court and the customary rituals of the social season. Thus one of Morath’s most famous portraits, that of the redoubtable Mrs. Eveleigh Nash (an Edwardian beauty turned society dowager), dates from this early stage of her career; as do the evocative scenes from Mayfair tailors, dressmakers, cocktail parties, and balls.

Another notable reportage story from Britain chronicled the couturier Christian Dior, who had been invited by the Duchess of Marlborough to stage a fashion show in aid of the Red Cross at Blenheim Palace in 1954. Morath takes us behind the scenes, to the Red Cross nurses in starched white uniforms and the Dior models in black couture dresses and pearls; both sets of women in their working attire, all of them graceful, while the great designer himself sits at a table, looking gently unassuming, as was his wont. (As Dior’s friend Cecil Beaton observed, “His egglike head may sway from side to side, but it will never be turned by success.”)

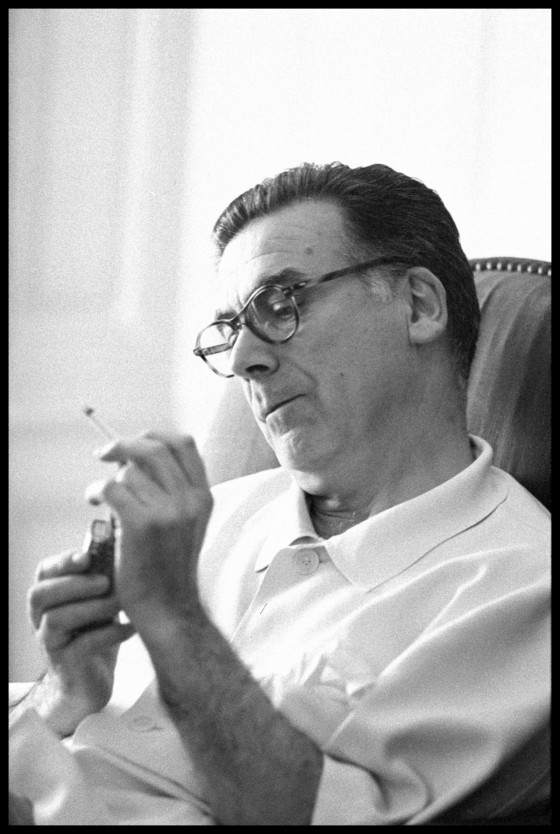

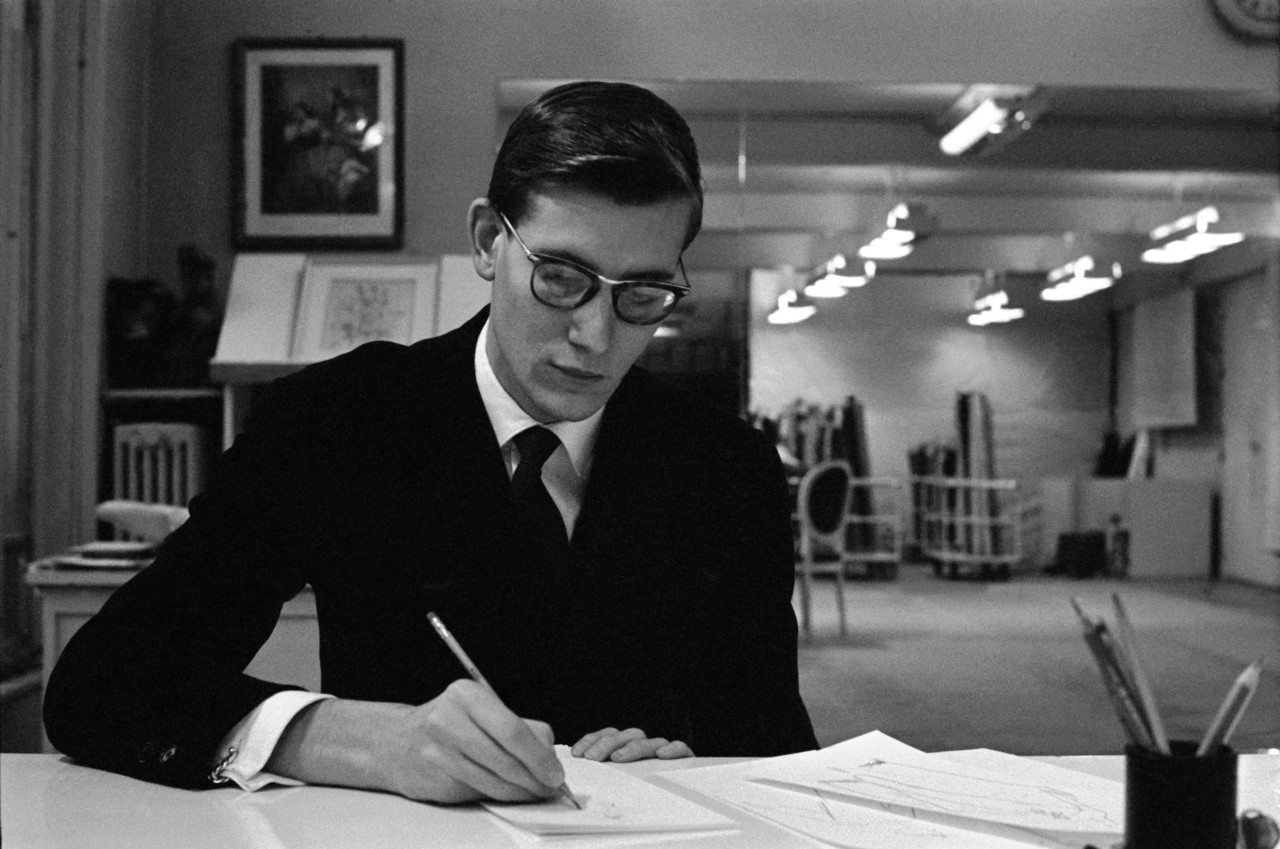

After Dior’s untimely death from a heart attack in 1957, Morath was on hand to document the debut of his brilliant young assistant, Yves Saint Laurent, who was promoted to head designer at the age of twenty-one. Her portraits of Saint Laurent— taken on the day before his first Dior collection, when he looks like a shy, studious schoolboy in his shirt and tie, intent on the task before him—were commissioned by Harper’s Bazaar. My guess is that Morath had first come into contact with the magazine via its influential Paris editor, Marie-Louise Bousquet (a long-standing friend of Coco Chanel and early champion of Dior, described by Beaton as “the brilliant Florence Nightingale of fashion”). Morath photographed Bousquet in 1955, animated as always, with her habitual cigarette in one hand, the other gesticulating to a copy of Harper’s Bazaar. Bousquet’s hands appear again the following year, having her palm read by Balenciaga’s colleague Ramón Esparza, her oblique reflection only just visible in a crystal ball beside them; a reminder, perhaps, of how fashion must constantly look to the future, whilst also reflecting the past. (Which might explain why several of its most famous practitioners have been so superstitious; Dior, for example, would make no important decision without consulting his fortune-teller.)

"A high priestess of photography... with the rare ability to penetrate beyond surfaces and reveal what makes her subject tick."

- John Huston

This was also the period when Morath first started working with the director John Huston; one of her earliest assignments was to photograph the stills for his film Moulin Rouge in London in 1952, which was to be the start of a lifelong friendship. Hence the wonderful sequence of pictures in this book of Huston dancing on Christmas Day at home in Ireland; including one with Morath in which I’m almost certain that she is wearing a Balenciaga dress.

Huston would later describe Morath as “a high priestess of photography,” a woman with “the rare ability to penetrate beyond surfaces and reveal what makes her subject tick.” But her camera is not simply a means to uncover a hidden truth, for these subtle images explore the relationship between polished veneers and what lies beneath; between darkness and light; freedom and confinement; convention and rebellion. (All of which is evident in her 1954 story of the “Beauty and the Beast” fashion contest in Paris, featuring couture-clad models with an array of dogs and other animals, some less com- pliant than others.)

Morath’s friendship with Huston was to play an important part in her personal life, as well as her career. In 1959, she travelled to Mexico to photograph the making of his film The Unforgiven, starring Burt Lancaster, Audrey Hepburn and Audie Murphy, a famously courageous American war hero turned actor. (Morath’s own bravery was called upon when Murphy fell out of a boat on a duck shooting expedition with Huston; after spotting him through her camera lens, dazed and in danger of drowning, she dived into the lake and hauled him ashore with her bra-strap.)

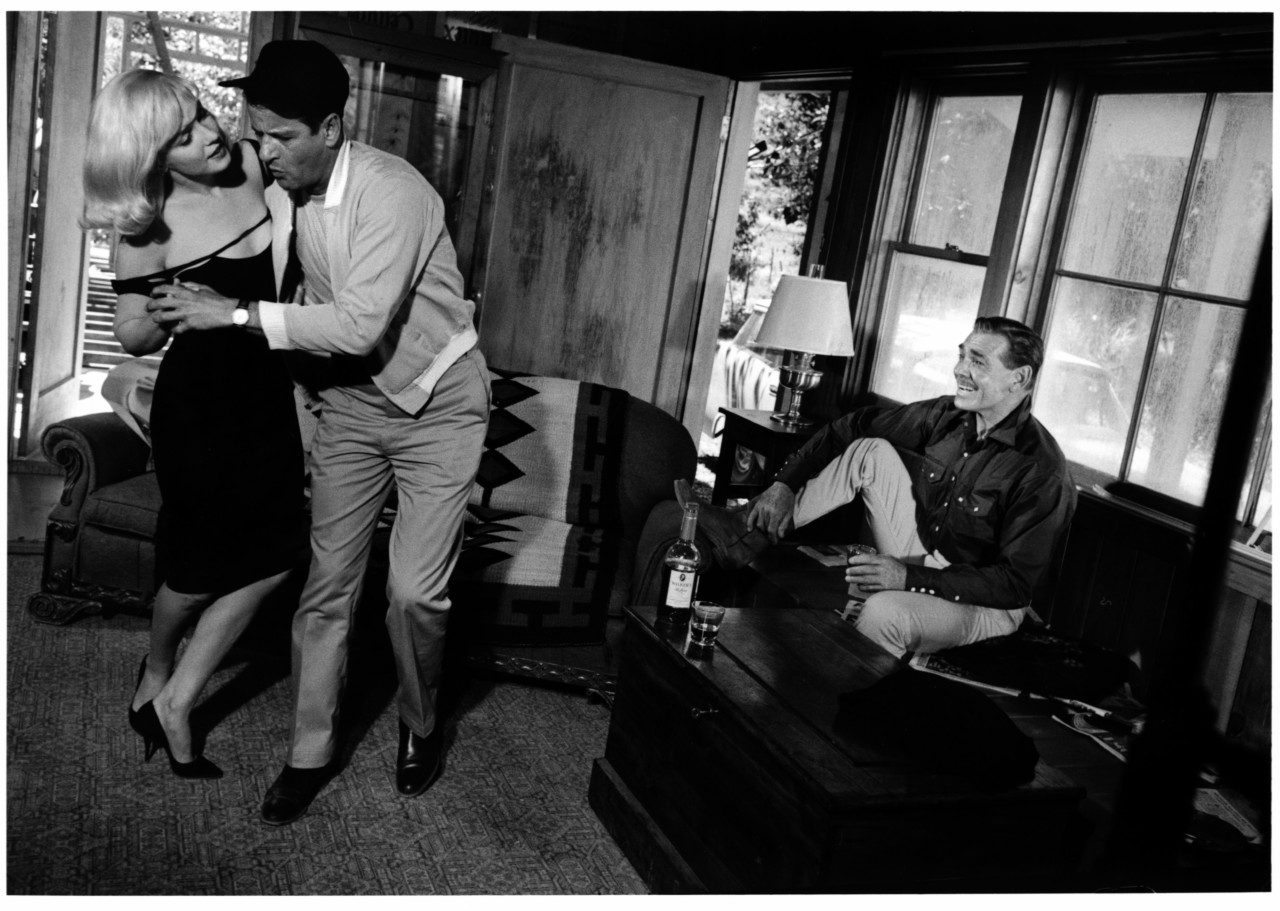

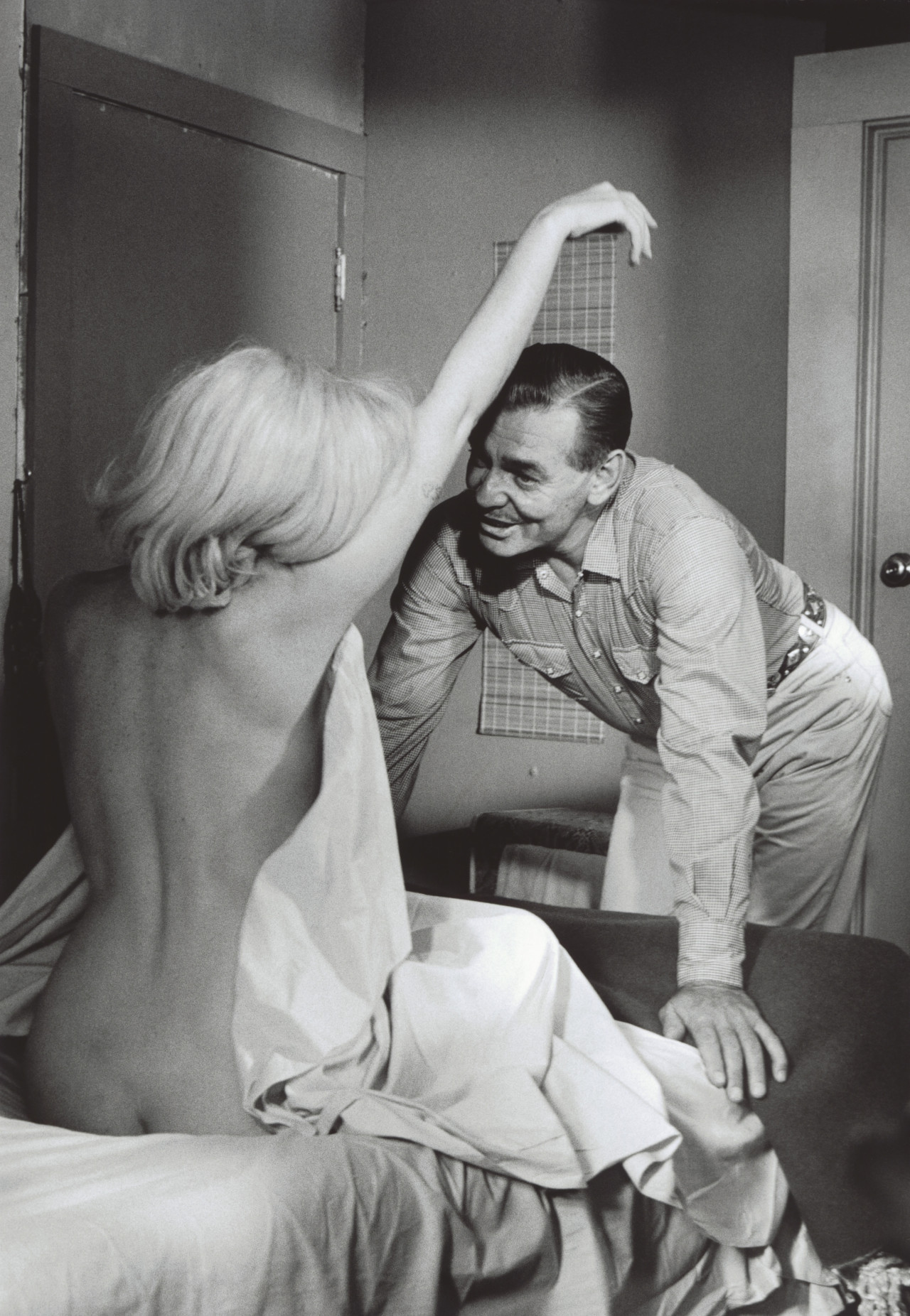

The following year, Morath visited the set of another of Huston’s films, The Misfits, accompanied by her Magnum colleague, Henri Cartier-Bresson. It was here in the Nevada desert that she first met the man who would become her second husband, Arthur Miller. The playwright had written the script for his then wife, Marilyn Monroe, who starred opposite Clark Gable in what was to be the last film for both of them. (Two days after the shooting finished, Gable suffered a heart attack and died less than a fortnight later; Monroe’s death followed in 1962, a year and a half after the release of the film.)

Miller’s marriage to Monroe was already under severe strain, and the shoot was a troubled one; she was dependent on prescription drugs and alcohol, and often late or absent during filming. Eventually she was hospitalized for two weeks during the production; in a later interview, Huston said he was by then “absolutely certain that she was doomed.”

Yet as Miller was to observe in an essay in 2006, Morath’s portraits of Monroe “are especially tender and beautiful.” There is no trace of exploitation or invasive prurience in these pictures; indeed, there is a sense of the photographer keeping a respectful distance. “Inge took comparatively few pictures,” recalled Miller. “When she pointed the camera she felt a certain responsibility for what it was looking at. Her pictures of Marilyn are particularly empathic and touching as she caught Marilyn’s anguish beneath her celebrity, the pain as well as her joy in life.”

When Morath was subsequently asked by the New York Times about the experience of photo- graphing Monroe, she described the actress as “kind of shimmery. But there was also this sadness underneath. A poetry of unhappiness. That was what was so mesmerizing, the twofold thing you got, the unhappiness always underneath the joy and the glamour…that was the poetry.” In the same interview, Morath added one more intriguing fragment to the story. “I once dreamt we both danced together, Marilyn and I. It was beautiful.”

After Monroe and Miller had separated, he met Morath again in New York. They married in February 1962, and their first child, Rebecca, was born in September of that year, followed by their son Daniel in 1967. Morath worked closely with her husband, collaborating on a series of acclaimed books that took them to China and Russia (her talent for languages proving as invaluable as her skill as a photographer). But she also found time to continue her own projects, including the tender portraits of her daughter and friends that are featured in this book, along with equally sensitive pictures of distinguished writers, journalists, performers, and artists.

“She made poetry out of people and their places for over half a century,” said her husband when she died; and that poetry continues to be as perceptive, subtle and beguiling today as it was at the moment of its creation. “Photography is a strange phenomenon,” she herself observed. “You trust your eye, and you cannot help but bare your soul.” Inge Morath’s soul still seems to be at the heart of her incandescent images, while her trust remains miraculously unbroken, even when darkness falls…

Purchase the book Inge Morath: On Style – Justine Picardie

Copyright © 2016 by Justine Picardie, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.