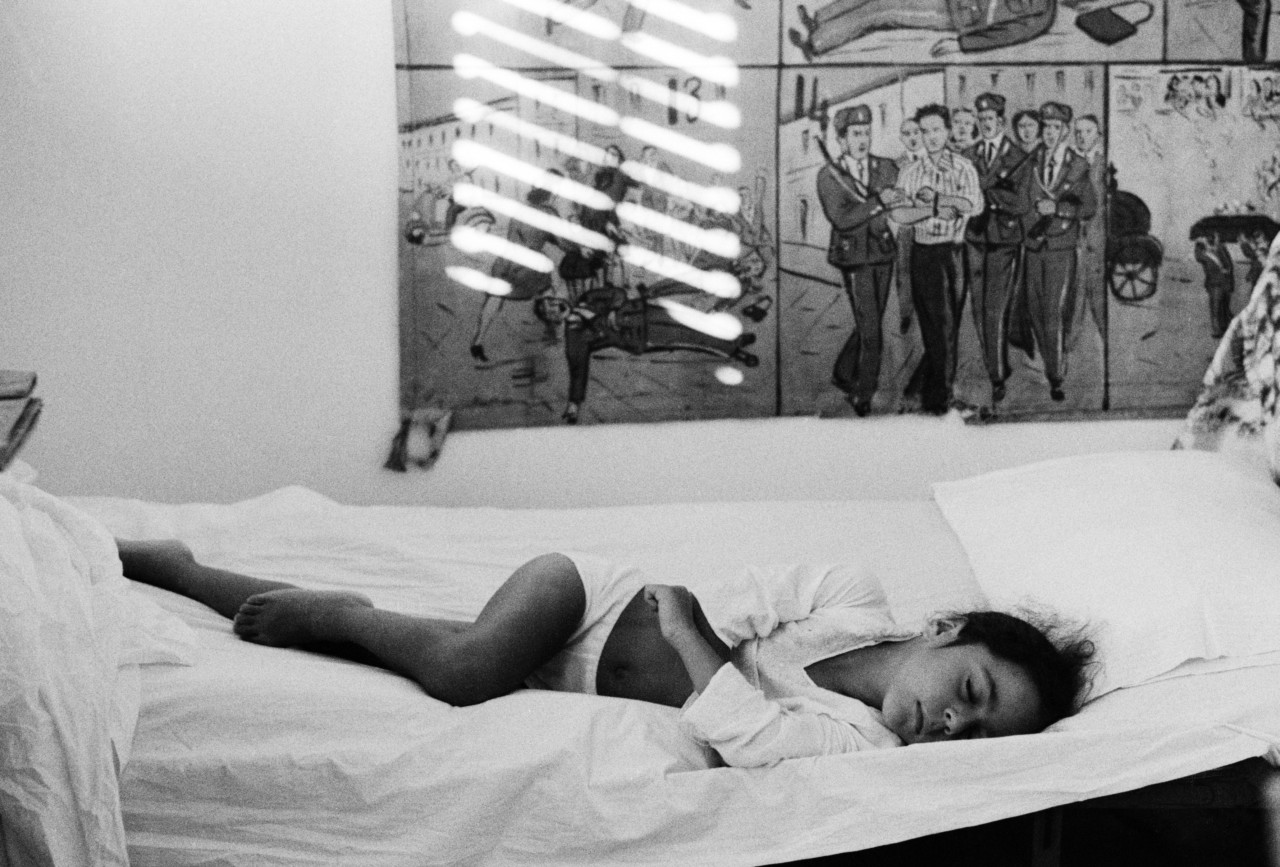

To Sleep, Perchance to Dream

Ferdinando Scianna’s evocative portraits highlight the mysteries of sleep

Sleep is one of the biggest mysteries of life, and so is dreaming. As Ferdinando Scianna writes, “Why sleep, people have asked, and they ask still.” The average person will spend around a third of their life asleep, and within that time frame, six years of it dreaming. Yet the interior world in which dreams play out means that no human can witness the dreams of others. For now, they must put up with intently watching a perfectly still sleeper, shut out, unable to know their dreamscape.

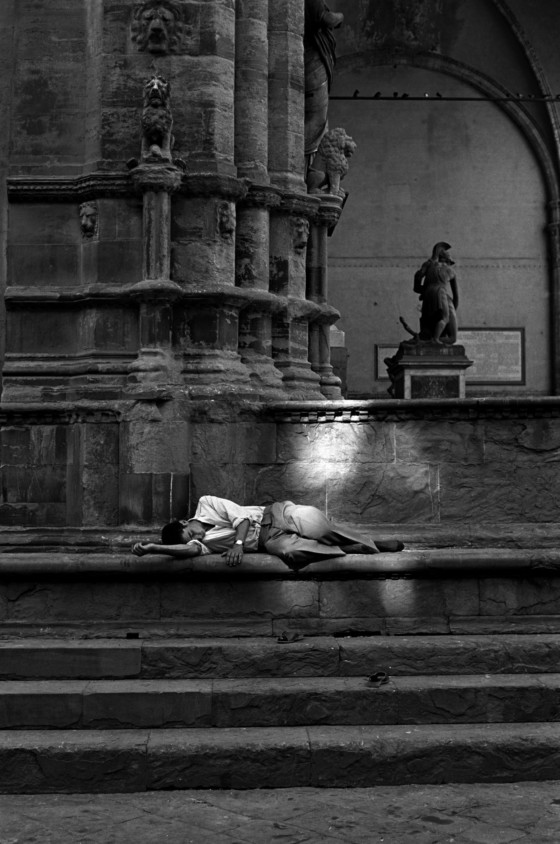

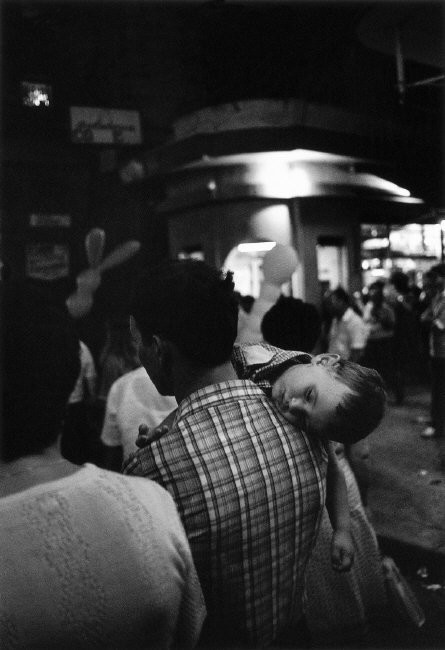

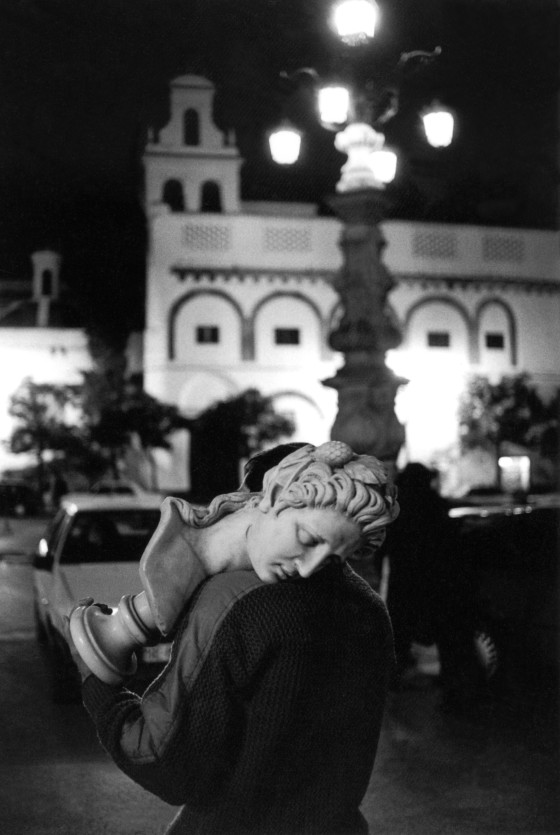

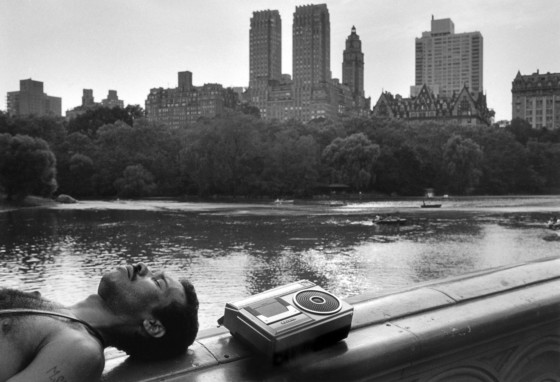

In his book, to sleep, perchance to dream (1997), Ferdinando Scianna reveals he has spent over thirty years undertaking this task, a theme that he only became aware of while sifting through his archive in search of a lost negative. “On this particular occasion I realized just how many of my pictures were of sleeping people; and that I had always been taking such pictures ever since I started photography, wherever the chances of life and of my job had led me,” he writes. His poetic black & white portraits of sleepers— whether found in nests of hay while farming, unforgiving city pavements, or within the comforts of another’s arms — all reflect the photographer’s fascination with the private journeys we take in our dream state.

"Sleep has but taken your form/And the color of your eyes."

- Paul Eluard

“Sleep is not only the time for rest, it is also the door through which one enters, or leaves, the immense ocean of dreams that some believe to be the most intense form of life,” Scianna writes. Dreaming is a universally profound experience, but its personal significance varies. While some interpret dreaming psychodynamically, maintaining they are self-referential and express the dreamer’s inner wishes, fears, and conflicts, others believe that our spirit is lured away to other realities, leaving our earthly body unattended. In sleep, the conscious mind checks out, forming resistance to waking life. As the French poet Paul Eluard wrote about a beloved dozing: “Sleep has but taken your form/And the color of your eyes.”

"I practice a kind of photography of the moment that generates form, and of the form that reveals the moment and perhaps also its meaning."

- Ferdinando Scianna

Viewing a person sleeping is a very different experience to looking at someone who is awake. Firstly, there is no gaze to contend with. In the act of leaving our physical self unguarded, sleep also opens us up to vulnerability. As Scianna describes, “to which we succumb almost secretly, usually in protected places, aware that we are delivering ourselves defenseless to the whim of others.” The photographer is aware of how his approach in photographing sleepers could appear as an intrusion into that person’s privacy. He writes, “It is not by chance that among these photographs there is only one of a little girl asleep in a decent bed, and she is my daughter.”

"Here time in the photographer's life intersects with time in the sleeper's life, the same, yet different."

- Ferdinando Scianna

While the sleepers that populate Scianna’s series are diverse —ranging from hapless sunbathers, a miner, a melon salesman, one performance artist curled in the sun-lit window of a gallery, sleeping children being carried by careful parents, exhausted pilgrims and migrants, the homeless, and even a fatigued ox kipping alongside its owner — all become equalised in sleep. Why they are sleeping is purposefully left unanswered, adding to quiet mystery of the photographs. As Scianna speculates, his subjects sleep “often in strange situations, whether from necessity, or innocence, or fatigue, or perhaps because they have nothing to lose.”

For Scianna, the act of photography and sleeping are inextricably linked: “I practice a kind of photography of the moment that generates form, and of the form that reveals the moment and perhaps also its meaning.” A photograph offers the opportunity to isolate a fleeting moment in the flux of life, but Scianna points out that he is capturing a portion of our lives that are “essentially motionless, but not stopped,” explaining, “Here time in the photographer’s life intersects with time in the sleeper’s life, the same, yet different.”