Herbert List’s Panoptikum

Colin Pantall speaks to Peer-Olaf Richter, Director of the Herbert List Estate, about the strange and surreal "Panoptikum," a photobook that was first conceived in Vienna in 1944, and published 79 years later.

If you have ever wondered how long it takes for a photobook to get published, spare a thought for Herbert List. In 1944, he photographed the strange waxworks in Präuscher’s Panoptikum in Vienna, planning to make his surreal images into a book. It is only now, 79 years after he made the pictures, that the book is being published.

In 1941, the Hamburg-born photographer was in Greece making the images he is best known for; erotically charged pictures of young men on the beach, alongside statues that seem to come alive in the heat of the Mediterranean sun, and images of architecture that take you back 2500 years to the golden age of Greek civilization. They are images tinged with sex, surrealism and a knowing idealization of body and form.

As a gay man with a Jewish grandparent and ties to a socialist youth group, List had left Germany in 1936 for his own safety. But, by 1941, German troops were approaching the Greek border. “The German Embassy told him he had two choices,” says Peer-Olaf Richter, Director of the Herbert List Estate, from his office in Hamburg. “He could stay in Greece and be arrested for treason and desertion, or he could return to Germany immediately. He tried to go to America, which didn’t work out, so he thought that rather than being imprisoned, he’d return to Germany.”

List struggled in wartime Germany. He failed to get accreditation as a photographer, and there was still a need to stay under the radar. However, because of his connections in publishing, he managed to get some assignments, many involving travel abroad, says Richter. “He got travel permits to leave the country, which for him was important because he didn’t want to stay too long in one place for fear of being drafted and sent east.

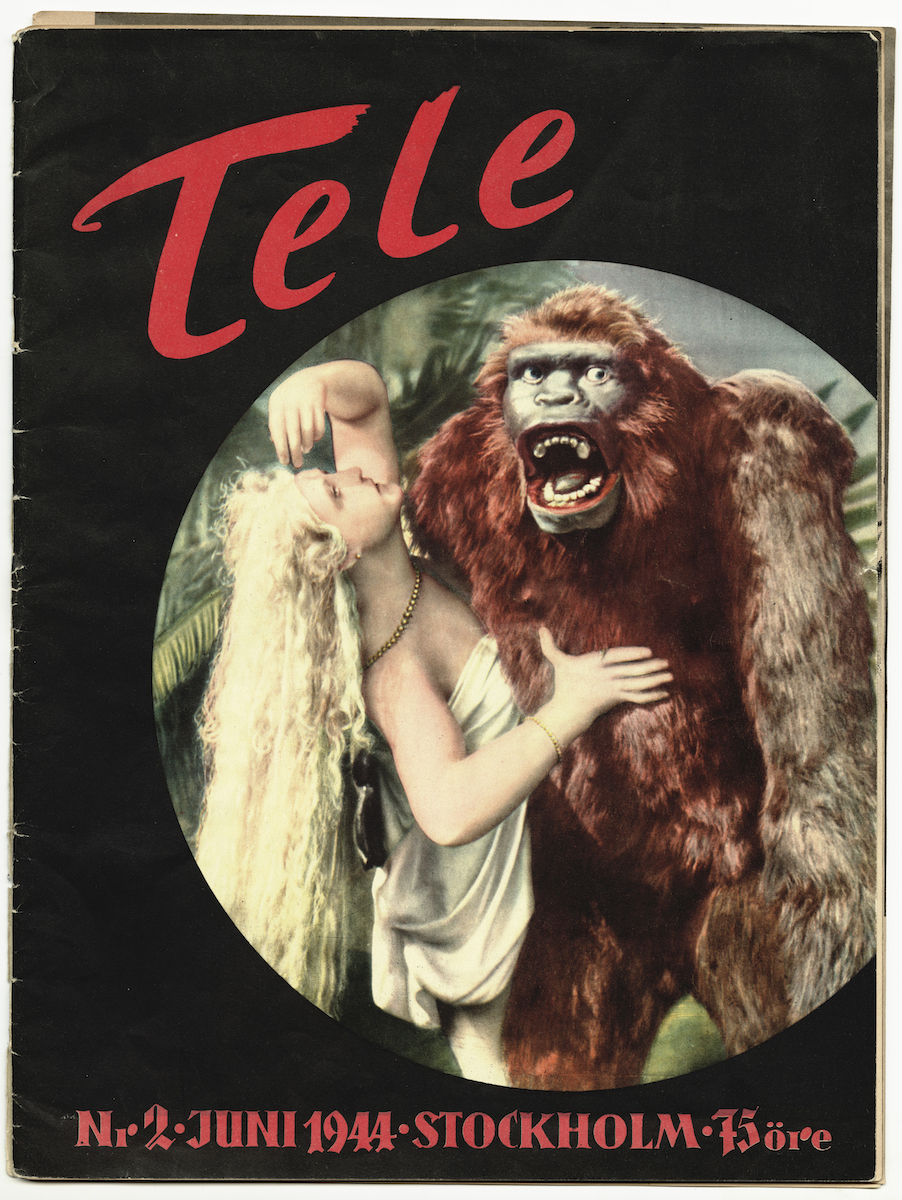

List was in demand for his architectural photographic skills, and instead of being sent to experience the horrors of what was happening in occupied Europe and beyond, he got to photograph churches and other cultural highlights in Macedonia, Greece and in Ukraine. “After that last big trip to Ukraine in the summer of 1943, he was approached by someone who was planning this publication, Tele.” It was a secret project of the foreign ministry; a project that was at odds with Hitler’s idea of total victory or total defeat. List’s collaboration with Tele would secure him a service deferment for the time being.

“They were more pragmatic. They knew that the war on the Eastern front could not be won. They had the idea that at some point there would be negotiations happening, and those negotiations would take place in a neutral country.” Top of the list of those neutral countries was Sweden. The organizers of Tele knew that it was too risky to print their magazine in Germany without Joseph Goebbels and his Ministry of Propaganda getting wind of it. So, Sweden was secured as a publishing base with the editorial headquarters first in Berlin, then in Vienna. Production was supposed to happen in secret in Sweden with printing machines shipped over from Italy.

While Signal, the dominant propaganda magazine of the Third Reich, focussed on delivering the Nazi ideological message, Tele turned to the cultural life of Europe. It was a magazine that would “employ softer tones… to promote sympathy for Germany,” that would show a selective appreciation of history, culture, and art.

It was a magazine that showed Germans in a flattering light, as people who appreciated music, art, and the finer things in life, people who, before the war, you might have sat next to during an orchestral performance, people whose not-so-hidden message was, ‘Perhaps we will one day do the same once all this nonsense is finished.’ The editorial policy of the magazine can be summed up as, ‘Let’s not talk about the war.’ Indeed, a picture from the magazine’s penultimate issue was captioned, ‘Let’s just not talk politics.’

That was how, early in 1944, List came to travel to Vienna to meet up with the editors of Tele (who had moved from Berlin due to ongoing air raids), says Richter. “There, he fell in love with the Panoptikum, and suggested that he wanted to do a photo essay on it.”

The Panoptikum

A waxworks museum in Vienna’s Prater Amusement Park, the Panoptikum was founded by Hermann Präuscher in the 19th century, and showed a variety of waxworks in a lurid mix of fame, horror, sex, murder and anatomical detail in equal measure.

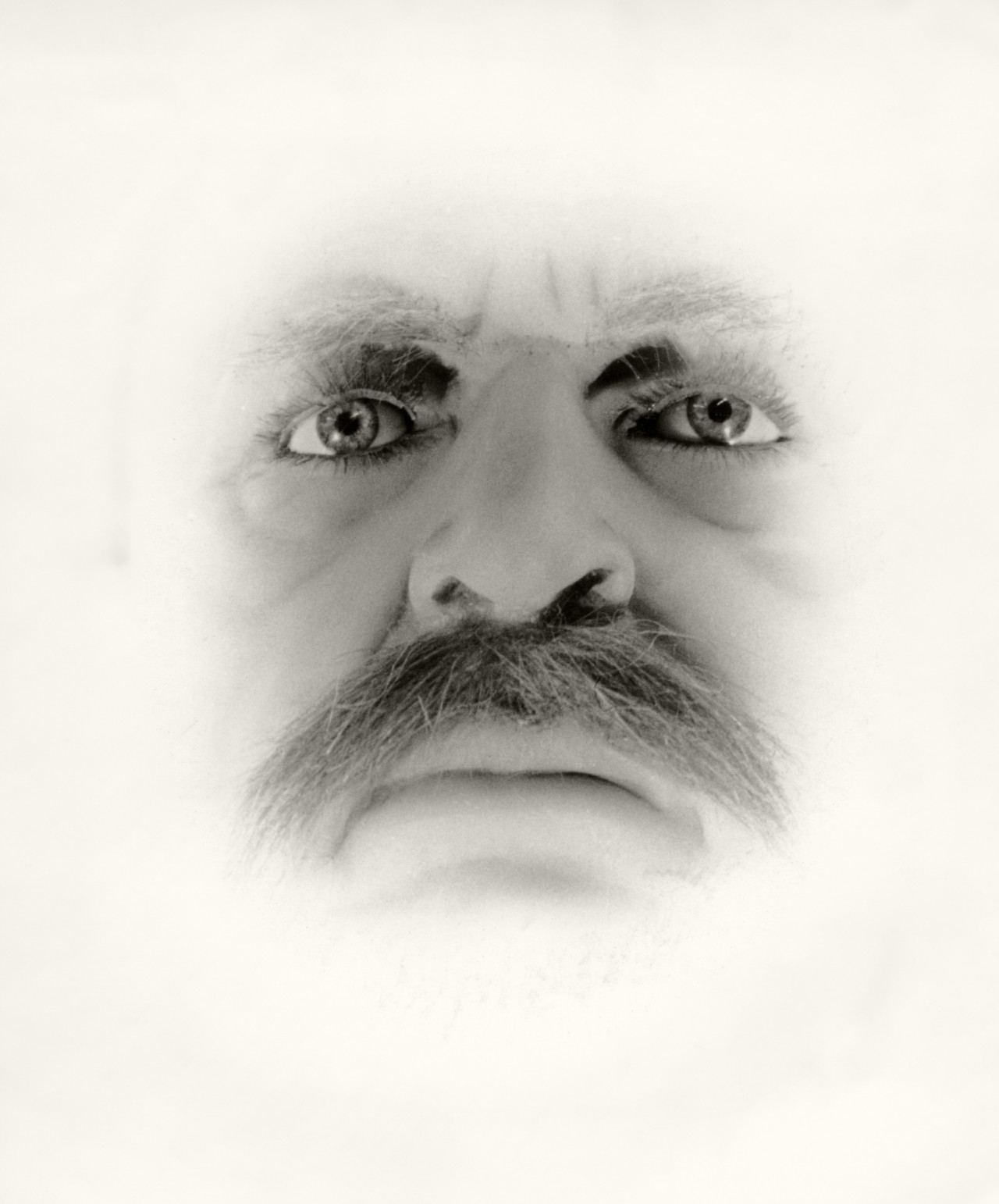

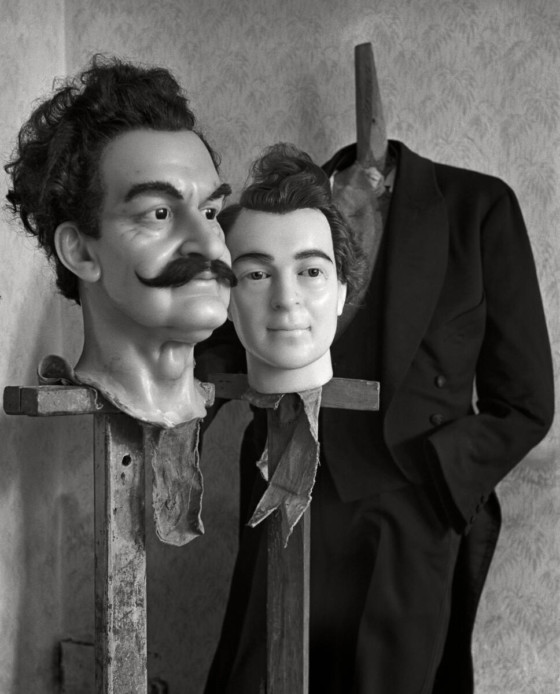

List had photographed waxworks and catacombs earlier in his career. He had a surrealist fascination for the way the dead eyes and glossy skin of the waxworks were offset by their expressive faces and lifelike poses. Like photography itself, these figures had a surface you couldn’t quite get to grips with, and hidden depths which aroused a sense of unease and the uncanny in the viewer. They existed in a half-world between life and artifice, between fantasy and reality.

Faces of mass murderers were placed next to sensationalist stories from around the world, the woman kidnapped by a gorilla being the prime example. And as Nazi influence in Austria deepened, so the exhibits started to be categorized as examples of race theory.

“It’s all a bit obscure and also bizarre because the erotic goes over to the medical,” says Richter. “And then part of the erotic is linked to race theory, where they would place the beautiful Roman woman against the beautiful Nubian woman. It’s very strange.” In List’s book, the beautiful Nubian woman is shown in sequence with the beautiful tattooed American, Slavic, Roman, and (a later addition) a German woman, classical ideas of beauty merging with titillation and the spectacle of the fairground attraction.

Written into the history of the Panoptikum was a visual history that showed how ideas and images changed over time. “List was interested in how different media interact,” says Richter, “how a story related by voyagers turns into a piece of art and then into a waxwork. Widely copied tales about African women being abducted by a gorilla inspired a sculpture by critically acclaimed artist Emmanuel Frémiet. After some sculptural variations, it turned into this waxwork (and later on a film) of a huge male gorilla taking away the blonde European woman to fit some sort of colonial horror fantasy.”

Criminals became heroes

“One of the waxworks (titled, ‘No Return’) shows this group of Austrian explorers in the Arctic. It was a significant moment for Austria as a crumbling empire trying to retain its power in the 19th century. It was not a successful journey (it was plagued by scurvy, tuberculosis, and seasick dogs), but they were able to rescue themselves and it became the sort of heroic tale that was reproduced in different forms of media and ended up being shown in the Panoptikum when List visited. But the figures that were used to show those Austrian heroes were previously shown in the criminal and torture chamber section.”

After the Nazis annexed Austria in 1938, they decided that it wasn’t culturally proper to show cruelty and torture, and so the figures of ‘criminals and dervishes’ were repurposed to become these symbols of Austria’s imperial past.

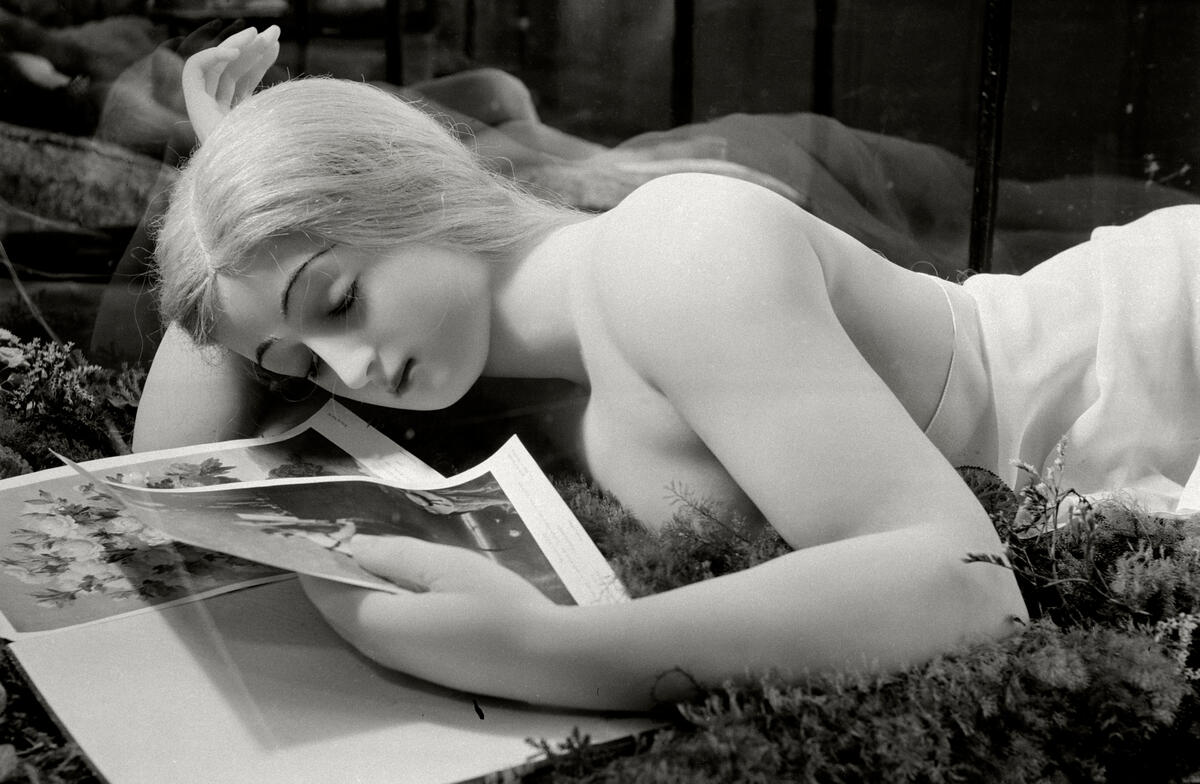

Most intriguing are the medical specimens. These once took pride of place in a special anatomical section of the museum, and the diseases, surgical procedures, and ‘instructive views’ mix shock, horror, and the erotic in a way that mirrors medical photography of the 19th century.

So we see a young man getting a nose transplant, with skin grafted from his upper arm to his nose, the lower arm tied to his head until the new skin takes. There’s strabismus surgery (for crossed eyes), trepanning with a hand drill, and the instructional view of a young woman’s chests, her head tilted to one side, eyes closed, mouth open, as her robe is pulled open to reveal her heart and lungs lying beneath her split sternum.

List’s pictures of the Panoptikum are the best-kept and final record of Präuscher’s collection of waxworks. The building housing the Panoptikum was bombed and destroyed in April 1945, with only a handful of the waxworks surviving.

Some of these images were published, in Tele magazine, to List’s dissatisfaction, but he was desperate to make a book of them. In the postwar years he made detailed notes on the different papers to be used, on typefaces and on design and decided to become a publisher himself.

“He was very detailed in how he wanted the book made,” says Richter. “He wrote texts, he had a friend doing graphic design. Complete layouts were made. We have two complete maquettes with us. And, actually, he went as far as producing printing plates for these images. The odd thing was that we had these sheets of printed paper, which were of different quality, and we could see that he tried to reproduce them himself at a time when you would assume that Germany was a complete shambles.”

But paper was not readily available to everyone in postwar Germany and required allocation on a project-by-project base through the allies governing Germany. There were questions of whether the images would pass American censorship laws (List doubted that Americans would understand the project), so the book was never published.

It was only when museums in Hamburg and Vienna showed interest in the project that the pictures came to be exhibited at Foto Wien Festival this year and published in book form. The book includes the version that List had originally planned back in the 1940s. In addition to that, it includes multiple texts on the Panoptikum, on waxworks, and the fascinating intersection between history, news, art, and photography.

“He prepared everything so well, it gives you the feeling that the Panoptikum must have been of central importance to him,” says Richter. “The project is his way of thinking about the medium of photography and his own artistic output. Especially the representation of the human body and the sculptural body in his work. Looking at his images of antique sculptures and male bodies from Greece there is always the question: what does photography do to the living body and to sculpture, and how does it both create an illusion and non-illusion at the same time? The wax sculpture and its photographic representation is another experiment on the topic with a more pronounced result. It articulates political implications in the representational process characterizing both mediums.”

First-editions of Herbert List’s Panoptikum are now available on the Magnum Shop.