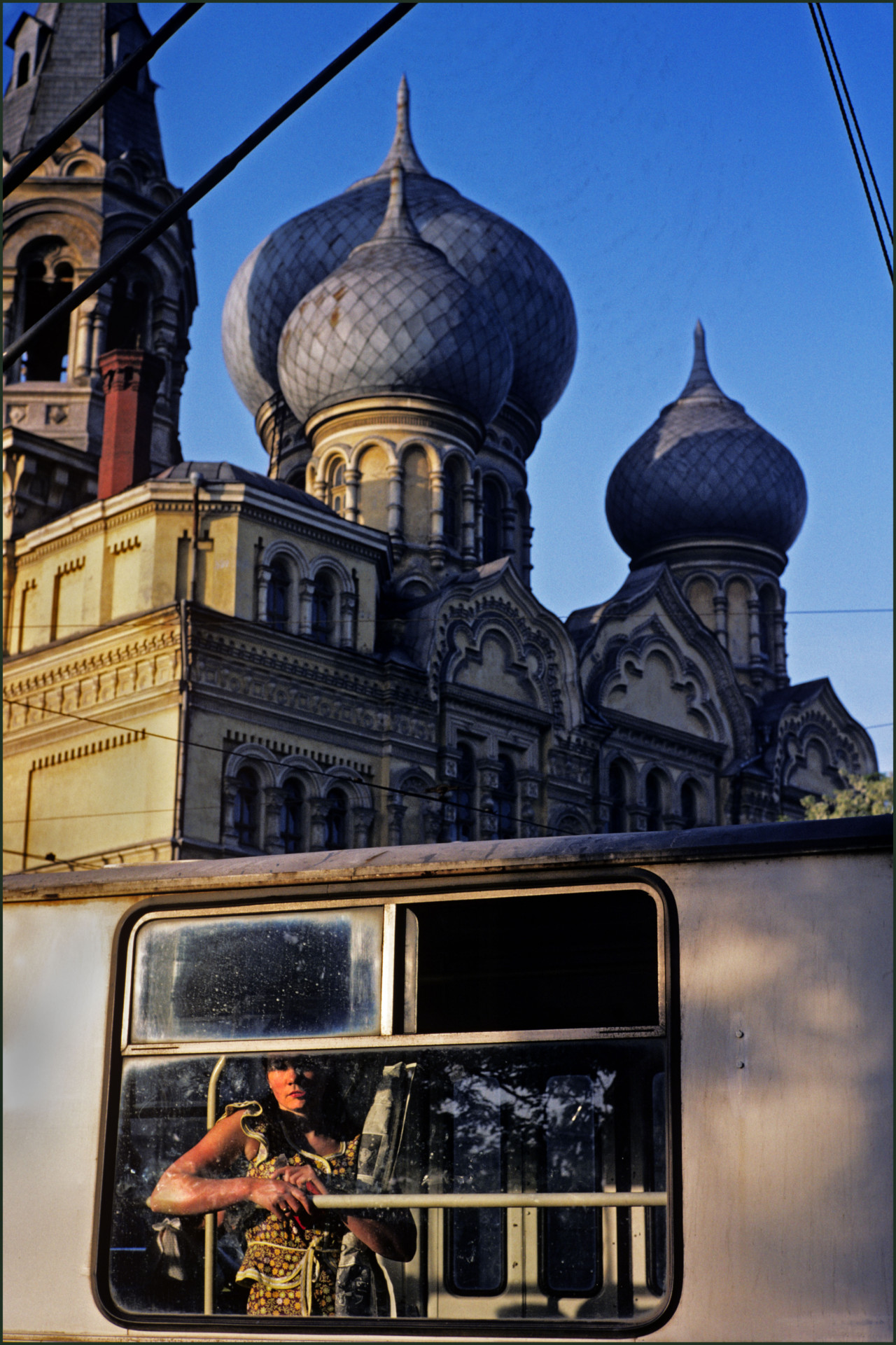

Ian Berry’s 1980s Portrait of the ‘Marseilles’ of Ukraine

A visit to the city of Odessa depicted a glossy vision of the country pre-independence

In 1982, Ian Berry travelled to Odessa in Ukraine to shoot daily life in the Soviet city. The place had informally been referred to as the Marseilles of the north for the culture and leisure activities on offer there — more reminiscent of a city on the Mediterranean than in the USSR. Ukraine’s third most populous city, it is situated on the Black Sea, a major transport hub, seaport and tourist center.

In February 2022, in light of recent aggression from Russia’s military and only days before the full invasion, Berry reflected on his time spent there while the countries were unified, recalling the tensions of photographing within the limitations imposed on him, and the at times surreal scenarios he found himself in.

Ukraine gained its independence in 1991, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Before that, coverage was strictly chaperoned. “Any visit meant foreign photojournalists had to be accompanied by at least an interpreter and a minder, not to help the individual, but to make sure they didn’t go into places deemed sensitive. ‘Sensitive’ covered a vast area; it was easy to stray off course without being aware that one had, because even innocuous, bland-looking buildings could turn out to be ‘sensitive’.”

Odessa’s architecture wasn’t very Russian — it had been influenced by both French and Italian styles. Notably, the neoclassical Potemkin steps were designed by Francesco Boffo, an Italian, and the city’s chief architect during the mid 19th Century. In Odessa in 1905, a workers’ uprising had been supported by the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin. Sergei Eisenstein’s filmic dramatization of these events, ‘The Battleship Potemkin’, included a scene where hundreds of Odessan citizens were slain on the great stone staircase, in one of the most famous scenes in the history of cinema. In actual fact, most were killed in the streets and squares around the city.

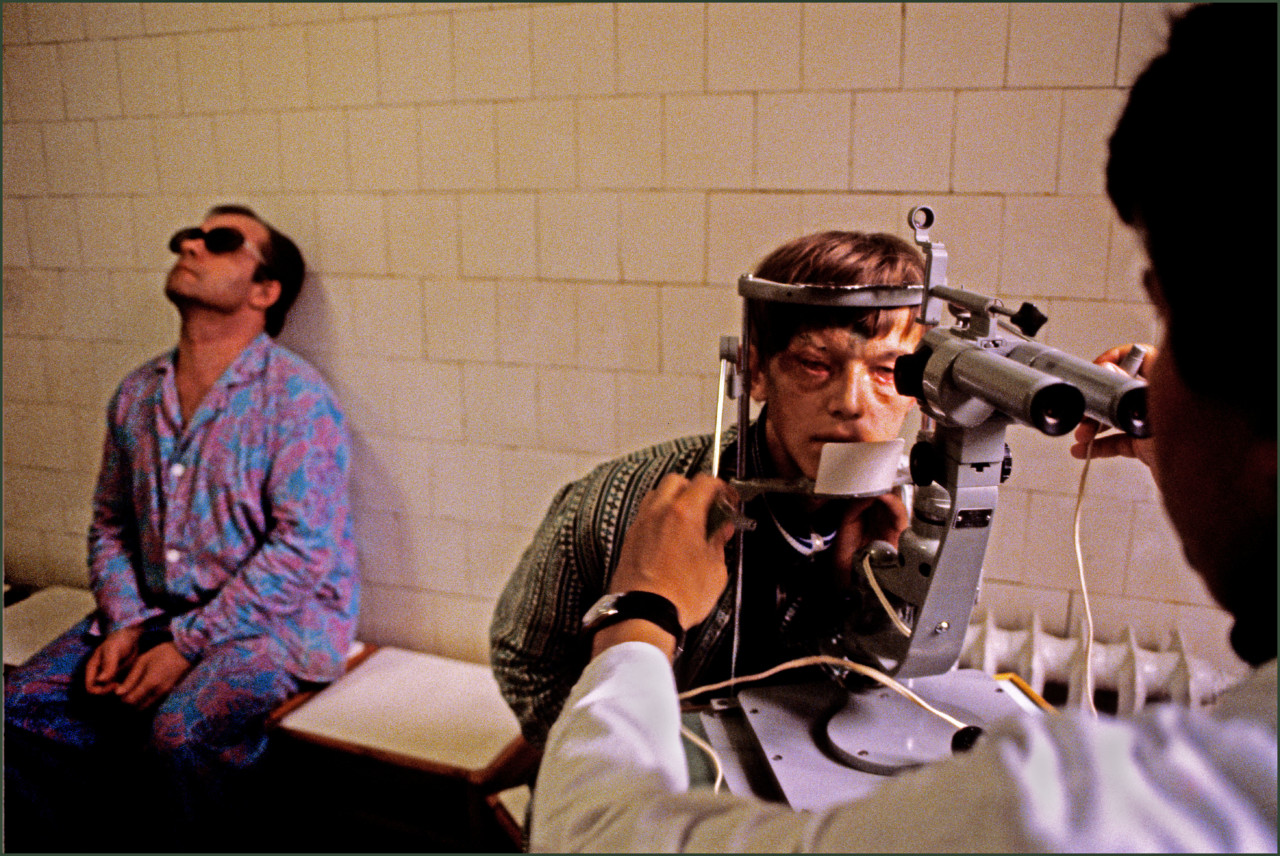

Making the series on assignment for GEO, Berry wanted to capture nightlife and youth in the place that was known for its creativity. “I wanted to photograph a nightclub but was assured there was nothing like that in the city,” Berry says, “However, a couple of days later, my interpreter said they’d found me one. Great!”

“I was taken to a hut, like a scout hut, where everyone was sitting around the walls listening to canned music, a completely static scene,” Berry says, “I took a few pictures, and let my interpreter know that it was sufficient. At once, the music was switched off and I watched everyone pack up and go home.”

“The ‘night life’ had been organised specially for me,” he says.

Berry recalls other, more nerve-inducing encounters with officials. “On this trip, my minder and interpreter knocked off at 5pm on the dot every evening.” Berry decided to venture to the port where he had been taken on tour before, this time unaccompanied. “A new, rather more interesting-looking ship had docked. Quickly I was surrounded by five sailors who escorted me to the port police building. At first they wanted my cameras, refused, then the film, which I again refused, all achieved with smiles and gestures and two mutually non-understood languages.

“When an interpreter arrived,” Berry says, “I’d had time to go to the toilet, take out my films and stuff them in my socks. After further interrogation, a call was made to the Russian Intelligence Services in Moscow, it appeared I was not a threat and was finally allowed back to my hotel – all very civilised.”

The relief didn’t last long — he received his curt dismissal from the country just half an hour later. A knock at the door revealed a rather more senior official who told the photographer that he was to board the 9am flight out of Ukraine the following morning, and that was the end of that particular trip.

"I’d had time to go to the toilet, take out my films and stuff them in my socks. After further interrogation, a call was made to the Russian Intelligence Services in Moscow, it appeared I was not a threat and was finally allowed back to my hotel"

- Ian Berry

What are Berry’s reflections on what has changed in the country, 40 years after made these images? “What is most visible on the streets of Ukraine today is the contrast of grinding poverty pushing residents to try to sell single items or a handful of leftover bits where they can, with the obvious wealth of a few residents, snug in fur coats,” he comments.

“It would seem that having strengthened ties with Belarus, annexed Crimea, threatened resource-rich Kazakhstan and Ukraine as well as eyeing the Baltic States, Putin’s aim is to reinstate the glory days of the USSR,” Berry says, “Apart from the perceived threat of a NATO and EU country on its southern border, it is not surprising that Putin would want to reinstate Russia’s access to a warm water port.”

All of this leaves bittersweet, uncertain feeling regarding Ukraine. “If the rampant corruption could be kerbed,” Berry thinks, “The country’s extensive acres of arable land put to good and proper use, and a better distribution of wealth, Ukraine’s future independent of Russia might be assured.”

Ian writes this at the end: “I was back in Ukraine a few months later, staying in the same hotels, recognised by everyone but nobody cared.”