In the Studio: Yves Klein’s Body Art

Rene Burri's photographs capture the artist and agitator making one of his famed body paintings in his Paris studio

In the Studio is a series dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists within their workspaces. Over more than seven decades Magnum’s member-photographers have captured images of the inner sanctums of many artists, often forging long-standing working or creative partnerships with them in the process. The images made in the studios of artists, in the company of their creatively imposing occupiers, reveal everything from insights on techniques and fabrication processes to illuminating clutter, reassuringly normal mess, and hints at the personal lives of individuals beyond their well-known artistic output.

You can see other stories from the In the Studio series, here.

Yves Klein was like an escape artist, always trying to free himself from the formal constraints of the painter’s canvas. An agitator extraordinaire, he became France’s most notorious creative figure, a position cemented by his premature death at the age of 34. He created many physical works but was also a maverick in the art of illusion, producing what he called ‘Immaterials’. In 1958, for example, he ushered thousands of Parisians into a gallery full of empty space. Ever the provocateur, he called the work, The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility, The Void.

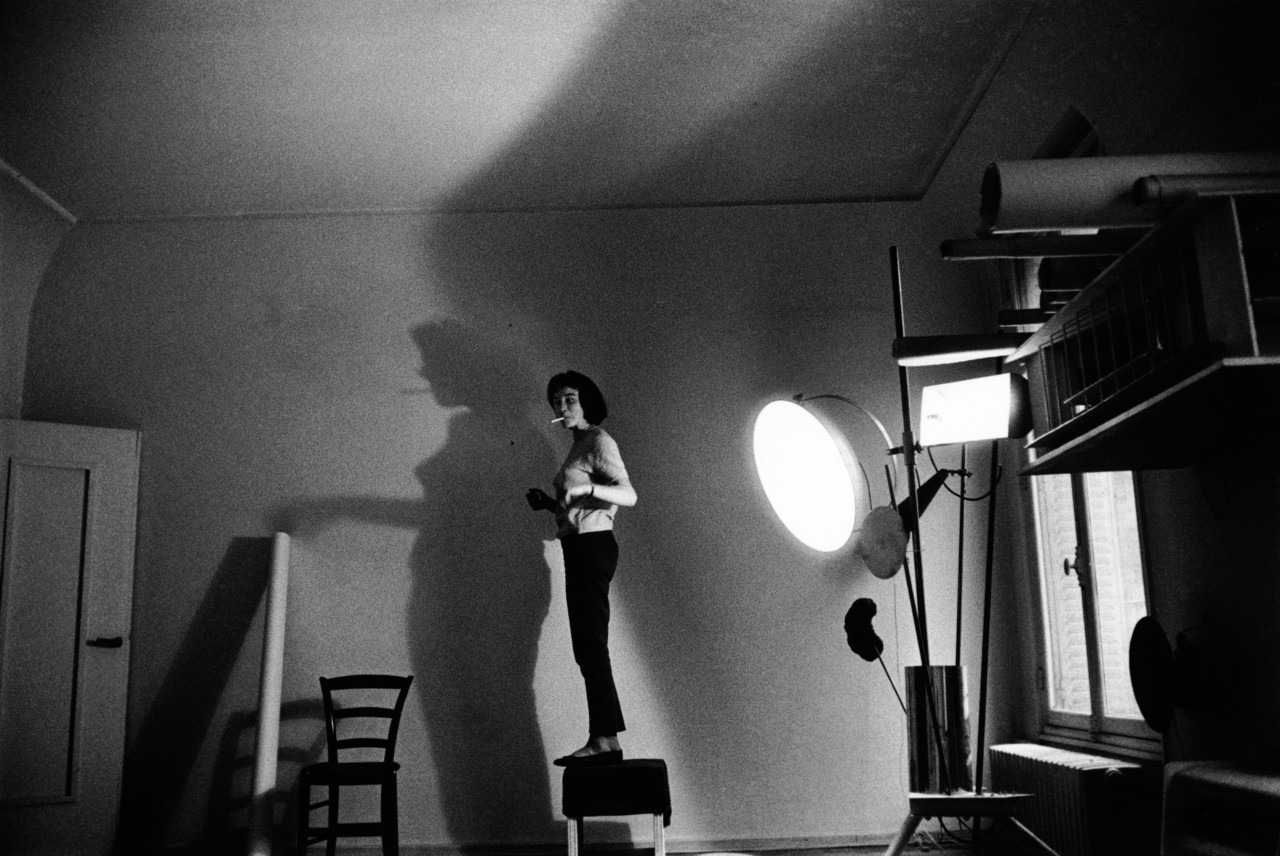

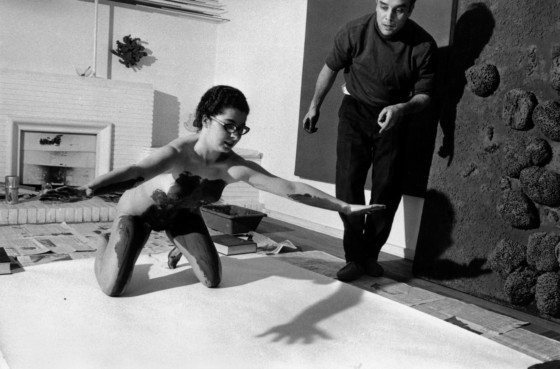

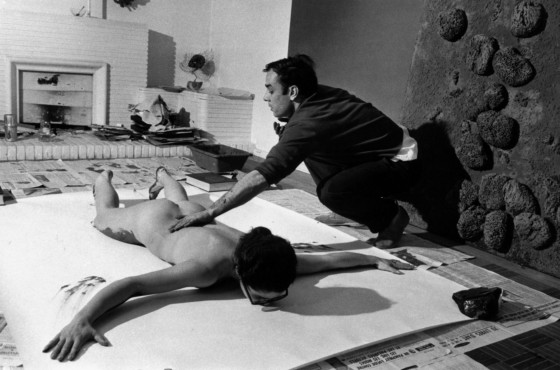

The paintings seen in these photographs, by Rene Burri, were created in Klein’s studio, in Paris’ 14th arrondissement, one afternoon in 1961 – only a year before the artist’s death. They show Klein’s pioneering practice of ‘body art’ – which usually took place in front of a live audience. Klein, dressed in a bow and tie, would direct the women from a distance as they covered themselves in paint and made imprints of their bodies, to the backdrop of a live orchestra.

These ‘happenings’, called Anthropometries, were some of the key events in the history of art and performance, marking a shift from paintings being something that happened on the canvas, to an exposure of the artistic process. Though there has been some criticism that Klein objectified the naked female participants, known as ‘Living Brushes’, the women have said they felt he treated them ‘entirely respectfully’, as collaborators rather than instruments.

The paint color he used, which cannot be seen in Burri’s black and white photos, is International Klein Blue, an electric shade that Klein developed in collaboration with a Parisian paint supplier called Edouard Adam. The pigment used is an ordinary ultramarine but the polymer binder allows the chromatic intensity to be preserved. Klein registered the formula in May 1960 at Institut National de la Propriété Industrielle (INPI) but never patented it. After its invention, the color became his central theme and he embarked on a series of monochromatic works, including the provocative performance pieces.

Though much of his work caused a sensation, Klein’s output was often misunderstood. The same year that Burri captured Klein happily at work in his Paris studio, Klein took leave to New York, taking up residence at the Chelsea Hotel. He had had a particularly disastrous exhibition at which he had not sold a single painting, and in a state of poverty and frustration, he wrote The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto. An excerpt reads as follows:

Having reached today this point in space and knowledge, I propose to gird my loins, then to draw back in retrospection of the diving board of my evolution. In the manner of an Olympic diver, in the most classic technique of the sport, I must prepare for my leap into the future of today by prudently moving backward, without ever losing sight of the edge, today consciously attained – the immaterialization of art.