King, Queen, Knave

The latest photobook by Gregory Halpern sheds new light on 20 years of change and return in his hometown of Buffalo, New York, tracing themes of memory, identity, and game playing

How do we deal with flux? Gregory Halpern’s latest book King, Queen, Knave, published by MACK, wrestles with the nature of cycles, identity, and games in an intimate two-decade exploration of his hometown of Buffalo, New York. Rooted in the personal, but revealing the universal, Halpern’s visual meditation on narrative perception and human experience invites us into a lush world of memory, myth, and materiality.

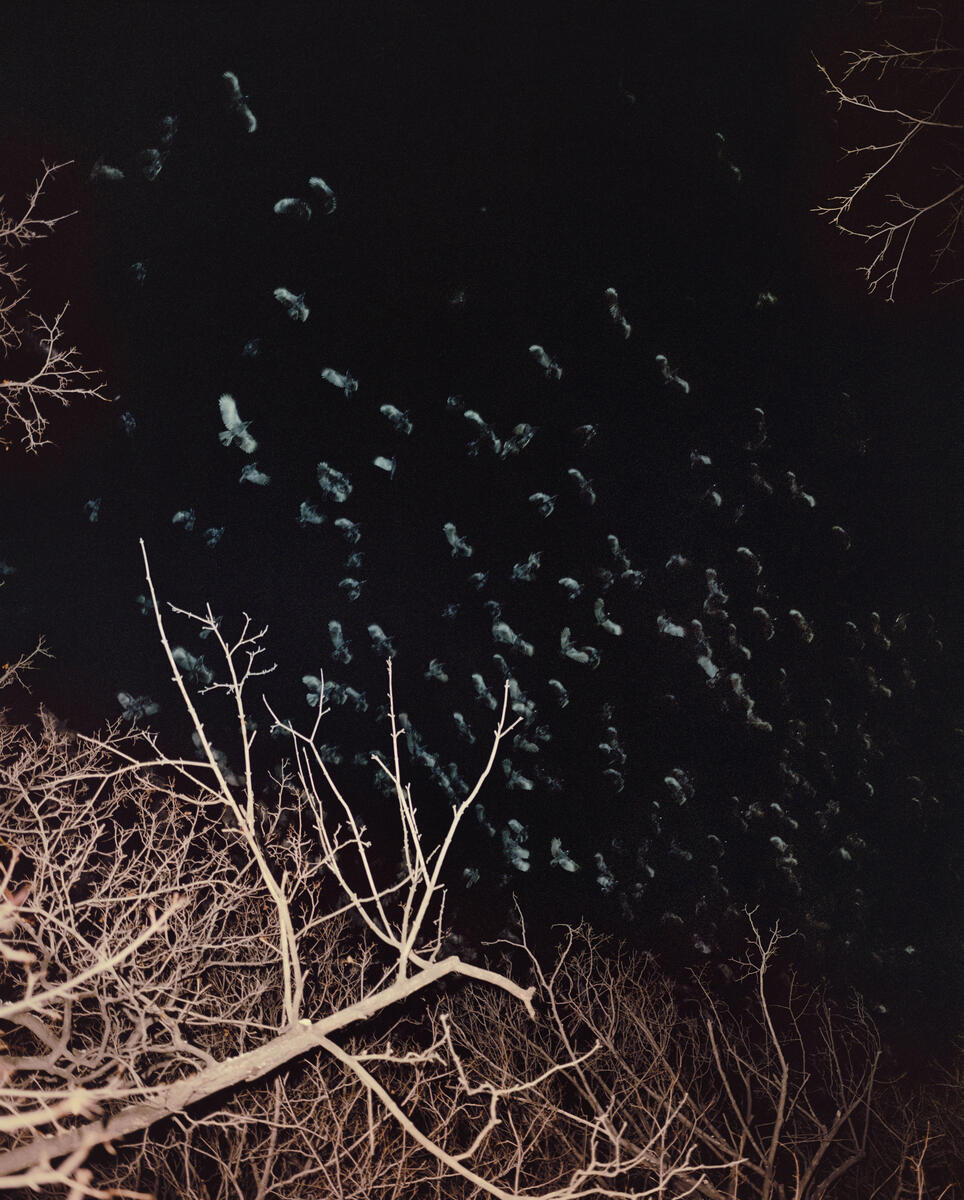

Halpern decided on the cover at the 11th hour — fitting for a project with so many generative delays and reinventions close to deadlines. For him, good covers don’t summarize the work or function as advertisements for what’s inside. Instead, he proposes a gateway, one that’s intriguing without over-explaining. King, Queen, Knave’s cover features an image from within the book, a rare choice for Halpern. Shot 20 years ago, the photo is eye-catching but deliberately ambiguous. Upon closer inspection, its initial cosmic grandeur gives way to something far more banal: the ceiling of an office building. This tension between the extraordinary and the everyday sets the tone for the book, acknowledging his role upfront as an “unreliable narrator,” or perhaps even a knave.

“I like the idea of a cover that exists as a work unto itself, that asks questions that intrigue and maybe frustrate the reader,” Halpern remarked at his recent presentation at Fondation HCB. He hopes the cover compels people “to open the book and then be an active reader, so that I’m not lecturing — I’m guiding.” He likens the relationship between creator and reader as “offering a hand to someone.” They can take your hand and go along with you, and they can drop your hand at any moment by closing the book.” By inviting readers to engage in this way, Halpern ensures that King, Queen, Knave becomes a collaboration between artist and audience.

The book reflects Halpern’s fascination with cycles — seasonal, historical, and metaphorical. Initially called 19 Winters/7 Springs, the project focused on Buffalo’s harsh winters, but evolved to include the vibrancy of spring and summer, balancing opposites like light and dark, hope and despair, and life and death.

Opening on the image of a white deer named April, a recurring figure, the work feels simultaneously mythic and grounded. April roams between Buffalo’s Old First Ward and a neighboring nature preserve, embodying themes of transition and duality. “White animals have been important in mythology and religion,” notes Halpern, drawn to April’s liminality. She appears three times in the book, acting as a subtle refrain.

Unlike previous projects, which are filled with vivid hues, King, Queen, Knave embraces a “muted, dirty kind of white” palette, reflective of Buffalo’s heavy winters. “The book opens with a lack of color, which is what happens after months of no sun,” Halpern explains. Yet he creates a visual rhythm by contrasting bursts of color and warmth with somber elements.

The title, King, Queen, Knave, draws on the history of playing cards, particularly the evolution of “knave” to “jack.” Traditionally, a knave was an untrustworthy person and the lowest-ranking court card. Halpern explains, “People were confused by the ‘K’ and the ‘KN,’ so card designers shifted to using ‘jack,’ which was a more colloquial, common term,” Halpern explains, intrigued by the idea that kings and knaves could be mistaken for one another.

“When you look at a person, all of these forms of being are there inside of us,” Halpern says. This notion extends to photography. A photograph captures the light bouncing off the surface of a person, but can it ever truly represent their essence? Or does it reveal something else entirely? This uncertainty, the question of identity, is at the heart of King, Queen, Knave.

"When you look at a person, all of these forms of being are there inside of us."

-

The book’s title also echoes Vladimir Nabokov’s 1928 novel, a tragicomedy about an Oedipal love triangle — published in English in 1968. Jerzy Skolimowski directed a film adaptation of the same title in 1972. Much of the imagery is tied to Halpern’s childhood in Buffalo and his ongoing relationship with the city. The photographs capture not just the people and places, but the city’s industrial decline and its transformation. For Halpern, Buffalo is as much a character as any of the people he portrays.

In one image, a building burns near the playground where Halpern spent his teenage years. In another, tulips bloom through spring snow outside a nearby house. These transitional moments, where seasons or events seem out of sync, are central to his vision. “I’m always interested in moments of transition,” Halpern says, reflecting on Buffalo’s “confused” seasons and landscapes, where nature and industrial decay coexist.

Buffalo’s industrial history features prominently, particularly at the former Bethlehem Steel site, once the world’s largest steel mill. Now overrun by seagulls and sunflowers, the site serves as a metaphor for cycles of life and death. “We no longer produce metal, except by recycling old or dead metal,” says Halpern.

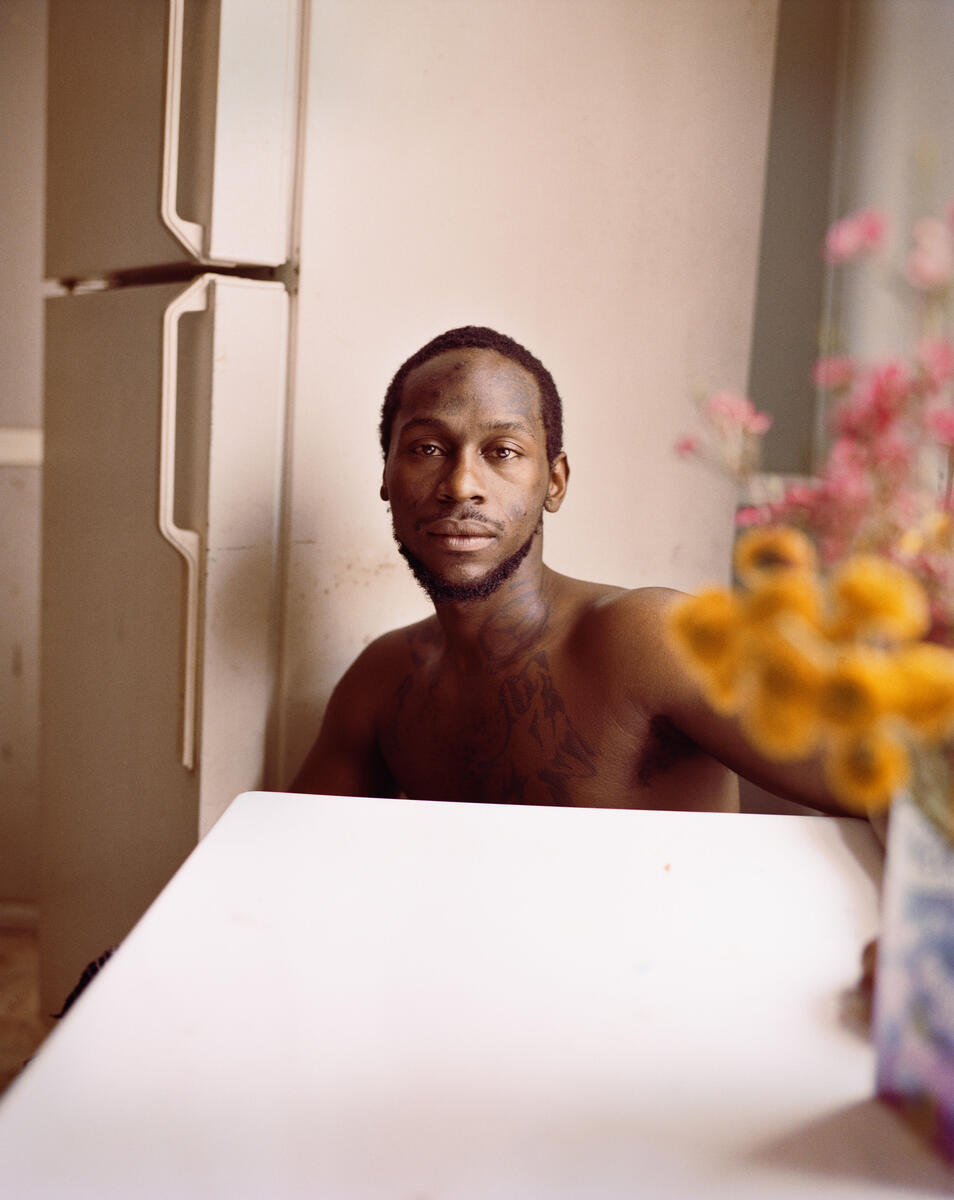

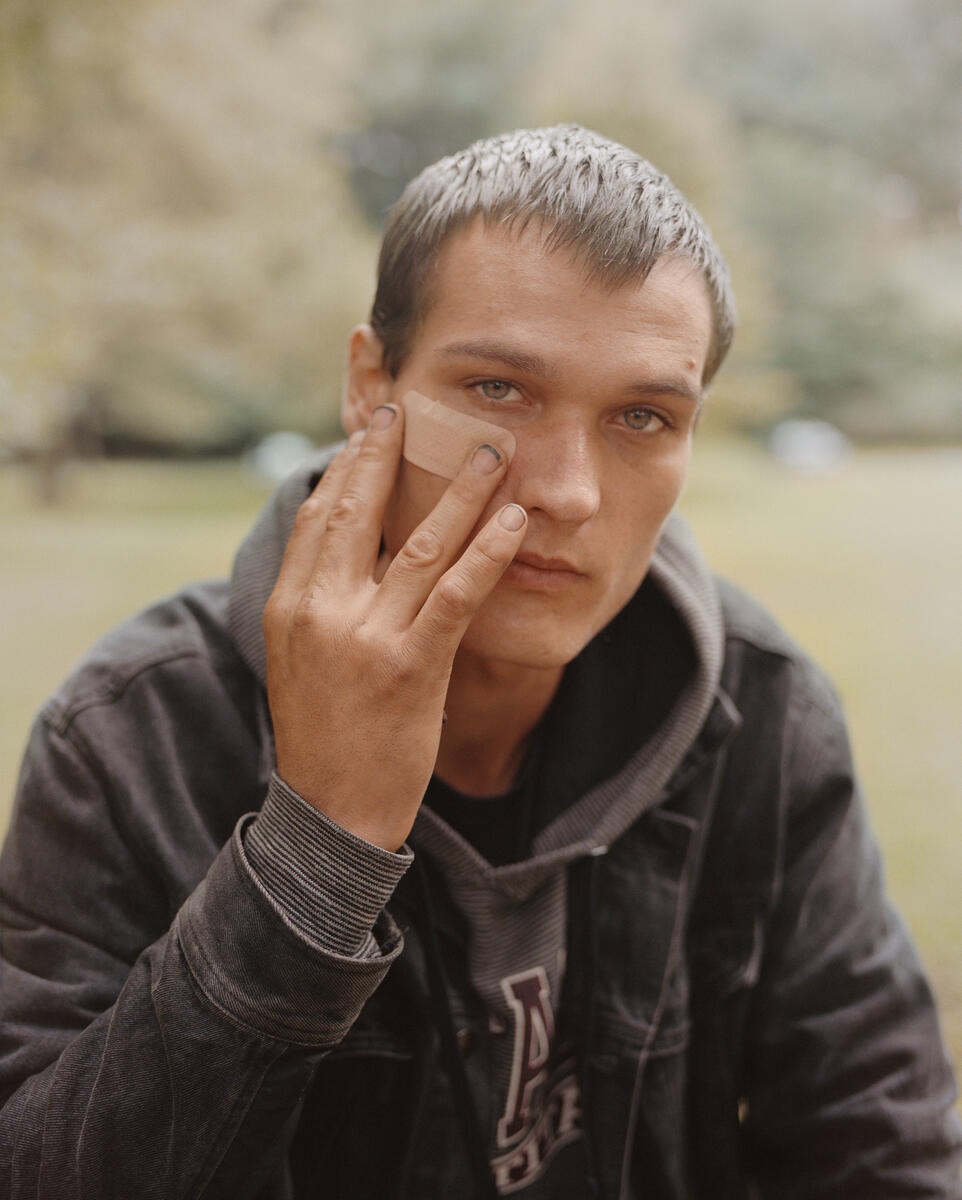

Many portraits in the book are tied to memory. One image features a boy Halpern photographed 20 years ago. Though he hasn’t reconnected with the boy, the photograph has remained a constant presence in his life. Other portraits reflect chance encounters with strangers during Buffalo’s snowstorms, when the city becomes eerily silent. One depicts a man named James, standing in the snow and gazing skyward. To Halpern, this image evokes gratitude and a sense of ascension, leading into the book’s closing image of ravens flying in the sky.

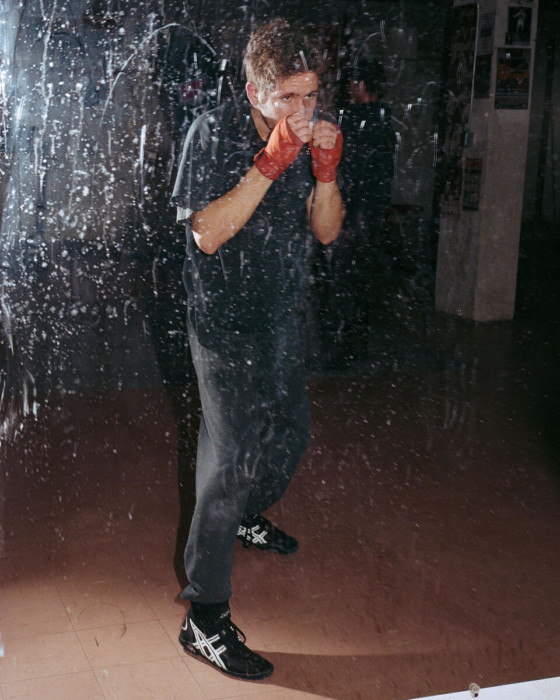

Throughout King, Queen, Knave, games recur, both literally and metaphorically. Halpern seems interested in their inherent power dynamics — the winners and losers, the black-and-white dichotomies, and the clear ends. One striking image shows a boy boxing, his face a mix of aggression and insecurity. Another captures a frozen chessboard. Even the book’s sequence mirrors a game, with carefully arranged moments of tension and release. “I’m thinking a lot about rhythm and pacing,” he explains, describing how “minor” images offer pauses before more grandiose photographs.

"The feeling of not knowing what you’ll find… that’s what makes me keep going."

-

King, Queen, Knave is a journey — through seasons, memory, and emotional landscapes of identity and place. It asks more than it answers, encouraging readers to actively engage with its images and themes. For Halpern, the relationship between maker and reader drives the project. By creating a work that’s both deeply personal and universally resonant, he hopes those who take his hand will feel compelled to explore further.

“The feeling of not knowing what you’ll find… that’s what makes me keep going,” Halpern says. “That feeling often ends in disappointment, because the longer you do it, the more you hope to come back with something — you can’t expect that though. But, there’s that feeling of finding something unexpected or magical, and that’s what I hope for.”

A limited number of signed copies of King, Queen, Knave are available on the Magnum Store.