Lorenzo Meloni: “I try to avoid images that contain easy answers and simplify the conflict”

Lorenzo Meloni shares his new project developed with Cristina de Middel, The Kabuler. Commissioned in partnership between Magnum Photos and Obscura, this collection of 55 images is created as a series of NFTs that are being minted to the blockchain today.

A newly commissioned collection of work in the partnership between Magnum Photos and Obscura is released today.

Lorenzo Meloni‘s The Kabuler has been created as a collection of Non Fungible Tokens (NFTs) that will be minted for collectors today. Here, we share the photos from the project and an extract from an interview between Meloni and Obscura Journal Contributor Danielle Ezzo.

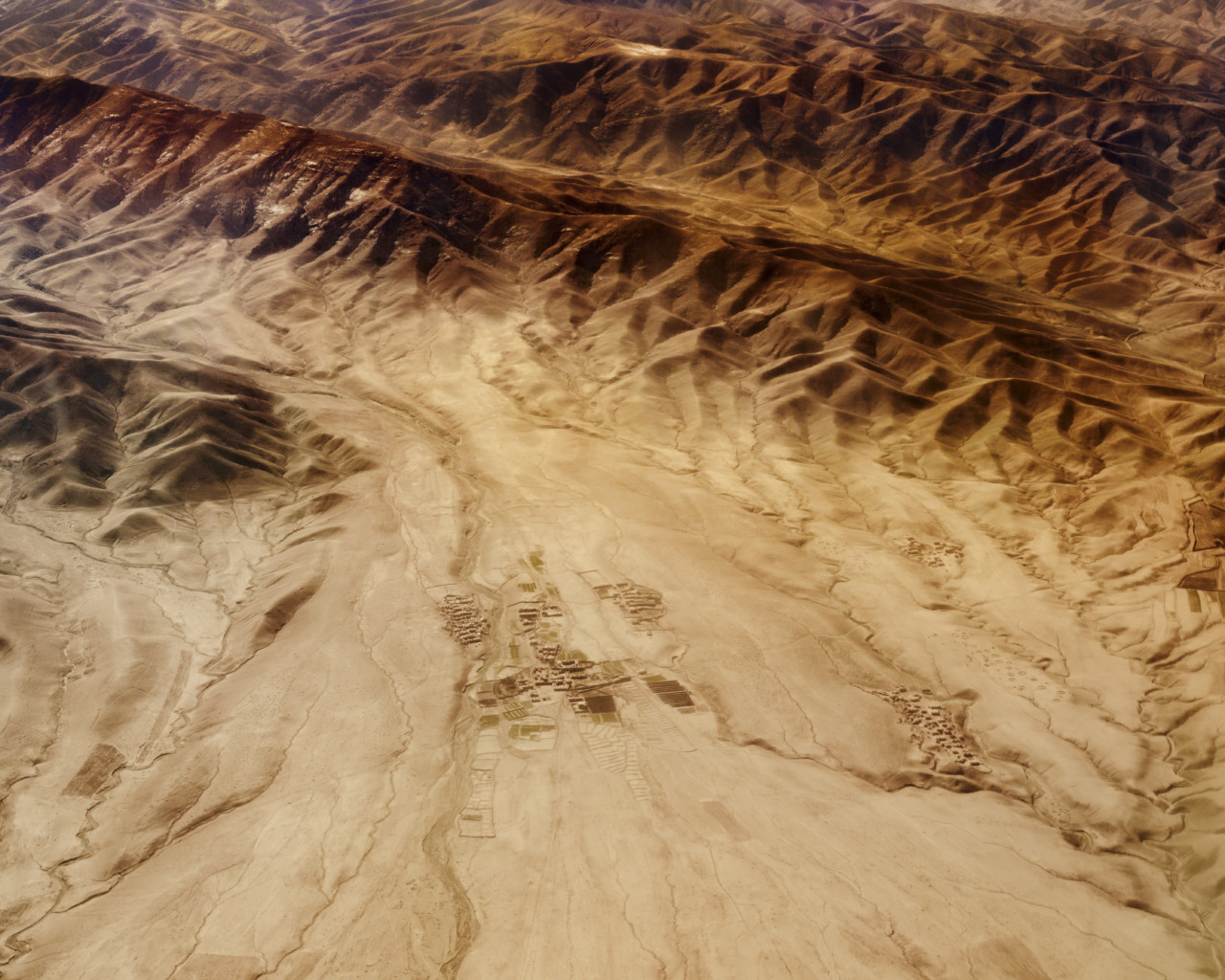

Afghanistan has been, for the last two decades, one of the most documented regions in the world, yet it remains a big mystery for the general audience who finds it hard to grasp the complete picture behind the constant reporting of breaking news.

This collection of 55 NFTs is the first part of The Kabuler project, in which Lorenzo Meloni partners with Cristina de Middel to produce a full panoramic photography of the current situation of the country borrowing the treatment that the media provides to other destinations and topics that are not under constant scrutiny. The project will use the sections of a traditional magazine to propose a complete overview of Afghanistan with an editorial structure, that should prevent the audience from falling again into dramatic expectations.

To learn more about the Magnum Photos and Obscura commissions, and see the list for future releases, please click here.

"When I chose this profession, I did it because I wanted to see the evolution of history in front of my eyes and not for the sake of seeing my pictures on an Instagram account."

- Lorenzo Meloni

Tell us about The Kabuler, your newest commission with Obscura?

During Magnum’s annual meeting, Cristina De Middel and I had a conversation about photography, especially about this sort of division between photography as an art form and photojournalism. Magnum has traditionally grouped these two souls within the same collective.

Reflecting on how art, beauty, journalism, truth and fiction can or cannot coexist together, we asked ourselves how we could unite our two visions and languages so that we could channel them into a single work representing a country we have never visited but about which we have both read a lot. From this conversation, the project Kabuler was born.

For the last two decades, Afghanistan has been one of the most documented regions in the world, yet much of the Western world doesn’t have a clear idea about the nuance of the conflict there. Can you tell us more about what you’ve learned on the frontlines? And why you think Western media misses the point?

The interesting part now is that the war in Afghanistan is actually over. I have been working on the aftermath of the war but in fact this is one of the first stories in twenty years about Afghanistan in a time of peace, even if the peace was not brought by a victory of the coalition of western forces.

Because of this the project is two-fold, you tell a deeper story about a specific place and people, but also point to potential issues in the canon of photojournalism. Would you say that’s accurate?

The problem is not photojournalism per se, but it is wider. The way of communication in general today runs at an impossible rate of assimilation. Everything has to be of immediate impact and everything has to happen in the time of a click or between one scroll and another. At the moment, even images seem to require too much concentration, so we have switched to short clips of just a few seconds to understand terribly complicated subjects.

When I chose this profession, I did it because I wanted to see the evolution of history in front of my eyes and not for the sake of seeing my pictures on an Instagram account. History demands its time and tends to seek to analyse and rationalise the causes and effects of events, rather than an extemporaneous emotional vision of the immediate.

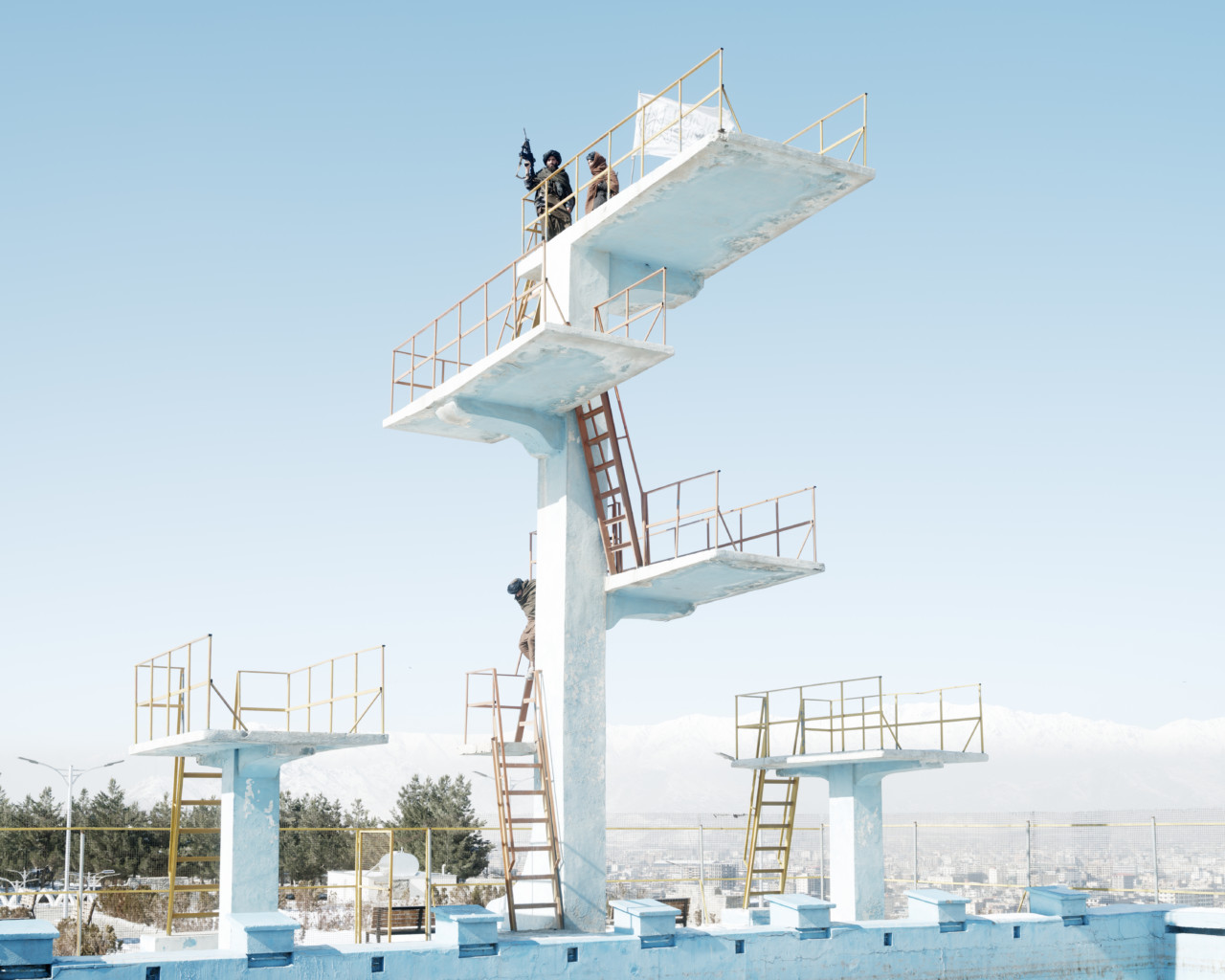

One thing that stands out to me in your images, is the layers of history: There are unoccupied or abandoned buildings that have become repurposed because of conflict. I feel like those images point to what you’re trying to get at with representing the complexity of a culture—a repurposed pool with tall diving boards turned look out tower. There is a history here—multiple histories—there was a before. Can you speak to that multiplicity?

At some point many of the images try to answer a question, or rather try to ask one. Many of the structures you see in the pictures are military structures built by the NATO coalition or during the time of Soviet occupation. To make an evaluation of the millions of dollars spent over the last 40 years between the various occupation military forces in Afghanistan seems almost impossible to me, but we are certainly talking about huge amount of money. And for what purpose? Why?

In the face of all this, can we still think that armies, bombings or any other kind of military intervention can be a resolution to international disputes?

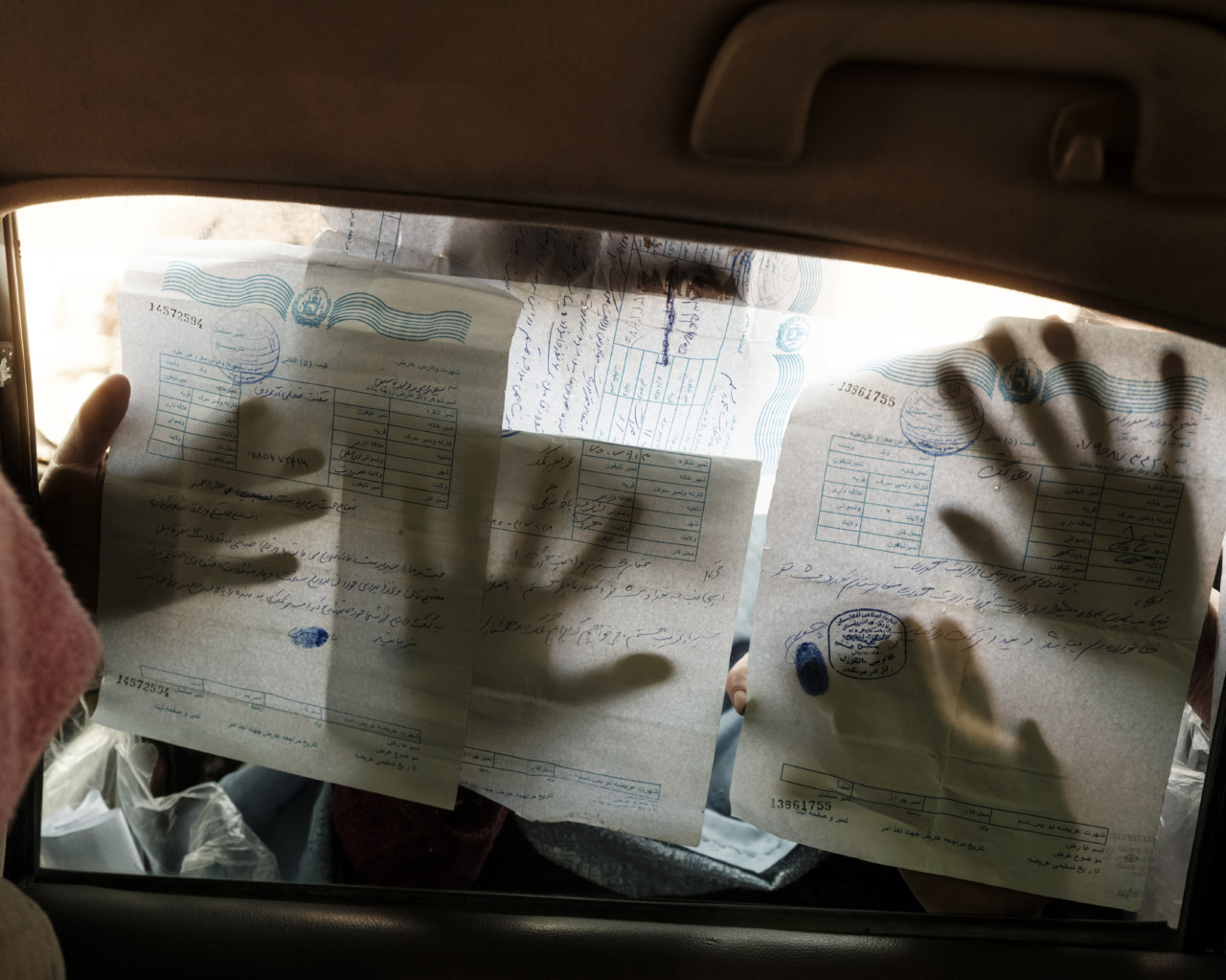

Place is such a large part of how this project unfolds. War and conflict photography anonymizes place and turns it into somewhere, anywhere, that’s not where I live. We often see images that focus primarily on actions being taken on other people too. Other being the operative word—air strikes, buildings decimated, people in pain. An audience may become desensitized to images like that because they are not people or places that they recognize. What is especially compelling about The Kabuler is we do not see that, but instead, we have close of portraits of real people; from which we can see their vulnerability. There are also sublime landscapes, familiar in their beauty. These components fly in the face of “otherness”, they aim to expose an inherent humanity. Tell me about this approach.

The visual representation and imagination we have of conflict is linked to ‘action’. Both cinema and photography, have mostly tried to exalt wars as something that happens ‘quickly’ and in an exciting way. On the other hand, reality is much more complex. When I started to look at all the pictures I had taken during my years working in the war, one of my first thoughts was ‘War is really boring, repetitive’.

During my work on the field, I spent entire days hiding behind walls, months in the same street, reaching ‘targets’ that were nothing more than a pile of rubble. I have photographed the same scenes of suffering a million times, happening the same way.

When shooting or editing my images I try to avoid as much as possible images that contain easy answers and simplify the conflict in the ‘act’ itself but I always look for something that is somehow metaphorical or contains more and even opposed layers. I like the idea to create a kind of before and after imagery of the conflict.

Two questions you posed in your artist statement for this project are: Is it possible to represent war in a different way? And: Does this dangerous work still make sense? Do you feel like you’re any closer to your answers?

I am writing this from a frontline in Ukraine where I am still asking myself the same identical questions. Probably the answers to these questions lies in the importance of continuing to ask yourself these questions constantly.

To view the full collection of Lorenzo Meloni’s Obscura Magnum Commission on the Obscura site, visit: obscura.io/magnum/lorenzo-meloni

To read the full interview, click here.