Ponte City

An intimate social portrait of Johannesburg's iconic Ponte City and its community of residents by Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse

‘Imaginary Cities’ author Darran Anderson on Mikhael Subotzky and British artist Patrick Waterhouse’s collaborative project ‘Ponte City’.

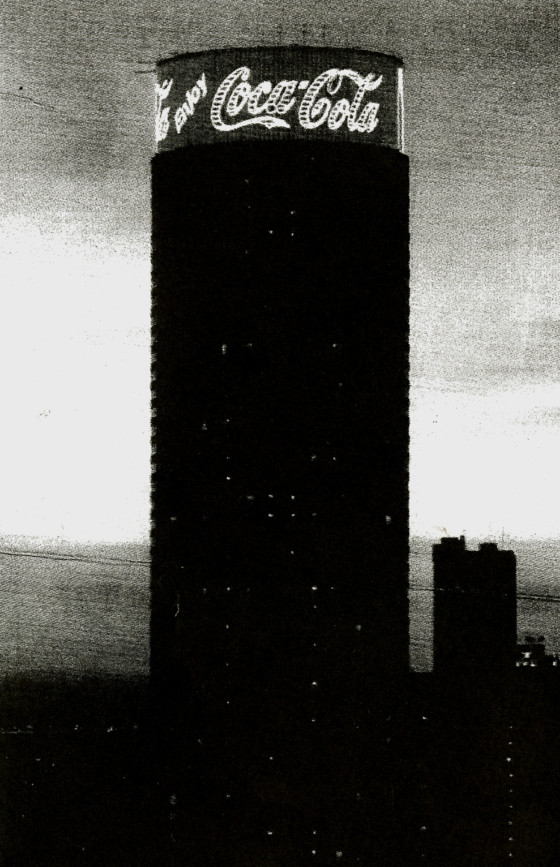

One feature of urban modernity has been that frequently we live our lives in surroundings that defy the human sense of scale. We travel so fast that sights which we might contemplate in detail at walking speed, we can only register fleetingly, or not at all. We regularly come face to face with buildings that are so immense and intricate that the mind has to simplify them as geometry rather than fully acknowledge that they are vertical space where multitudes of actual people work and reside. We build as if we’re gods and then view the results like infants.

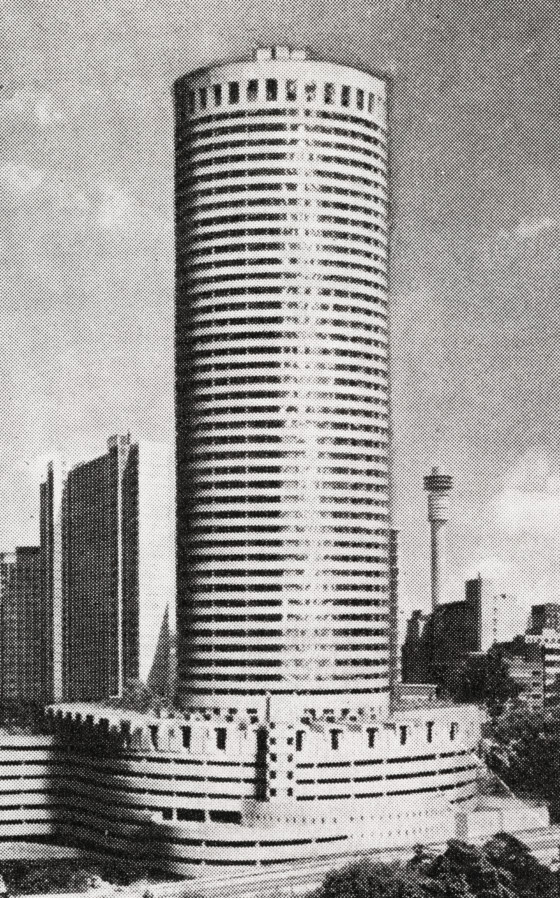

Ponte City, Johannesburg, is one such place. It seems beyond biblical in dimension. In their series of photographs, texts and found documents by the same name, South African photographer Mikhael Subotzky and British artist Patrick Waterhouse present a building that, at certain angles, appears dystopian, even apocalyptic. In one shot, a group of penitential clergy kneel on waste-ground with the building in the background. It is unmistakably contemporary and yet it resembles something between a medieval illuminated manuscript and an Abrahamic vision where prophets chant down the unjust city. We are in the realm of the celestial or the diabolical and yet it is all just concrete and glass.

The initial impression or rather impact, is unmistakably architectural. Subotzky’s photographs of the interior of the cylinder-shaped tower are stunning. They appear like the inside of a vast silo, a power station or, given the wreckage and rising dust in some of the shots, a sarcophagus enclosing a catastrophe in the manner of Chernobyl. The repeating floors and windows extend away into the light as if into infinity, lending the perspective a science fiction sense of impossibility (or the Inferno staring up at Paradiso).

As with the greatest science fiction, there is a paradoxical sense of the scene being simultaneously futuristic and ancient. Such a place must exist only in the realms of fiction; the fever dreams of Piranesi perhaps, Bentham’s all-seeing Panopticon or the infernal industrial environment of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. The brilliance of Subotzky and Waterhouse’s Ponte City series is that they demonstrate that this is only a shell for something more interesting and profound; the lives of the people who live there.

"...the building seems to speak so much to the condition of the city"

- Mikhael Subotzky

The building looms large in the collective psyche of South Africa’s largest city and not just in an architectural sense; “Everybody in Joburg has a Ponte story”Subotzky tells me, “the building seems to speak so much to the condition of the city.” While the facades may seem endlessly repetitious, each window contains a room and inhabitants.

Ponte City escapes the dehumanising overarching perspective of those who view the world from a god’s eye view or as voyeurs from the outside. This intention informs the multi-faceted approach of the project; there are photographs but also a range of documents outlining the designers’ intentions, in renderings and blueprints, and the particular character that each and every resident placed on their surroundings, “Our experience of Ponte was about these multiple stories that floated around the building, sometimes contradicting each other, sometimes reinforcing myths. So the multiple approaches seemed to be the only way of capturing these endless stories and their relationship to each other.”

At the heart of Ponte City is a sequence of elevator photographs taken in the building. They have an atmosphere of intimacy and tension. The characters they capture are revealed in portrait, or at least suggested as we see their domestic spaces, but also, in cases, they shield themselves. In such a confined environment, the slightest nuance of dress, expression, gaze or body language is amplified. There is flamboyance, detachment, hostility and curiosity. It was also a way, for the project’s creators, of moving beyond the aesthetics of the building and into the very soul of it, “We’d go up and down for hours, making ourselves feel sick, and whoever wanted to be photographed, it was a chance to get to know them and get their contacts so we could bring them a copy. It was literally our way in.”

"Ponte City escapes the dehumanising overarching perspective of those who view the world from a god’s eye view or as voyeurs from the outside"

- Darran Anderson

‘Live in Ponte – and never go out’ exclaims one newspaper cutting, capturing both the utopian and dystopian elements to the development in one headline. By contrast, Ponte City shows us that people by their nature quietly subvert the plans others have for them. Subotzky and Waterhouse’s Ponte City shows that people resist the plans of others implicitly, by simply living the lives they choose. The grand whitewashed masterplans, coming from above and faraway, become outdated and redundant. It’s the individual citizens that make the city, in many instances from the ground up. They do this often in spite of, rather than because of higher intentions – particularly the bureaucratic fashions of eviction and regeneration.

The building, however awe or dread-inspiring, is simply a shell for their lives to take place. “In and amongst these two incredibly strong forces (modernism and apartheid ideology)”, Subotzky points out, “you have the multiple lived lives of those who reside and resided in this building. And all of their stories aggregate into both a mythology and specificity of experience that seemed to define and explain not just the building, but the broader city of Johannesburg. Our project was always about these stories. The architecture and the mythology and the ideology were just containers that, while of course interesting in themselves, were a way of containing the project.”

Ultimately, the tower of Ponte City is a multiplicity. We see this in the windows, doors and televisions Subotzky and Waterhouse have captured; none of which have the same view. Even those who were evicted from the building leave not meaningless trash but idiosyncratic relics of their lives. In showing us the world within the façade, the pair have demonstrated photography’s great ability to allow us to see, with clarity and complexity, even when our senses are overwhelmed.