Celebrating 50 Years of the Isle of Wight Festival

David Hurn remembers the naked delight of the festival’s seminal 1969 and 1970 shows

The halcyon days of the Isle of Wight festival—from 1968 to 1970—were a spectacle of bare bums, beehives and big, big crowds, at least according to David Hurn.

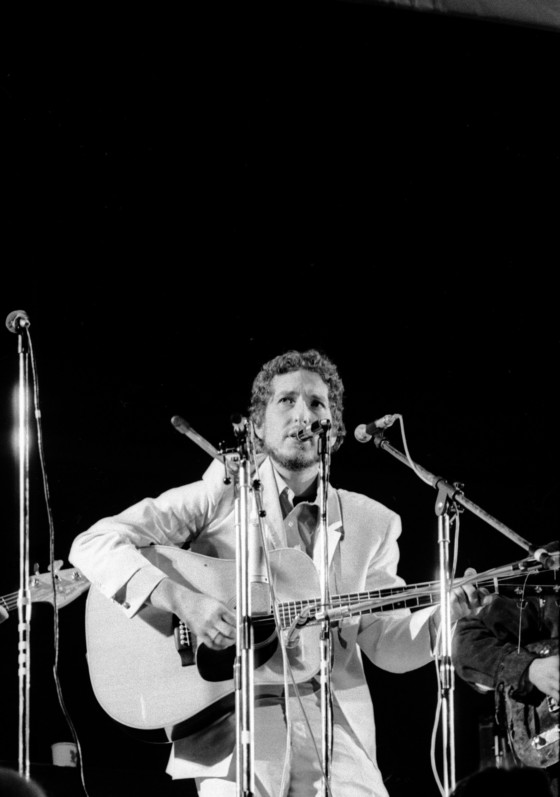

The Magnum photographer documented the iconic festival in 1969 and 1970 and though the line-ups included Bob Dylan, Miles Davis, The Doors and Joni Mitchell, it was the people, rather than the pop stars, who captured his attention.

“The majority of the photographers concentrated on those on the stage and I did it slightly differently because I focused on the enjoyment of the people watching the people on the stage,” says Hurn. “That’s reality as one sees it.”

Hurn documented spectators’ wild dancing and even wilder fashion sense. “It was the flower power era so there was extraordinary sense of exaggerated colour and dress,” he says. Even the everyday acts of washing and eating were elevated from the ordinary. Hurn captured them as communal, DIY affairs, with groups of friends gathered around a rudimentary water tap or makeshift tin-can cooker.

These small scenes offer a glimpse into festival life but it was the colossal crowds—far exceeding what the organisers had planned for—that give the sense of history in the making. In 1969, 150,000 people turned up while in 1970, more than half a million swamped the Island. The promise of this many peaceful people in one place was what first led Hurn to cover the event.

"I went because the rumour was it was going to be large—bigger than anyone had ever seen"

- David Hurn

“I went because the rumour was it was going to be large—bigger than anyone had ever seen,” Hurn says. “And the spectacle of that amount of people interested me.” Locking in the ‘crowd’ pictures was the first thing that Hurn did when he arrived. “There was an enormous temptation all the time to be in the thick of it,” he says. “But I would have made the decision to go and get that picture done because you know it’s a useful picture to have.”

Hurn approached the festival as he would any other ‘en masse’ story; following the same “three-picture” pattern that he used throughout his career. He looked for the ‘crowd picture’ that tells you how many people are there, the ‘character picture’ that shows similar-looking people converging and the ‘interaction picture’ that involves people doing something together. “You would have at the back of your mind those three types of pictures,” he says. “And continually try and photograph them.”

Though in his mid-thirties at the time, Hurn had a reverence and respect for the celebration of youth on display, in all its Technicolor glory. So much so that, when hundreds crowded a beach to get naked and be at one with the crashing waves, he felt the only natural thing would be to join them in the de-robing. “I remember feeling that you were obliged to take your clothes off as well, you felt out of place if you didn’t,” he explains.

Surprisingly, Hurn seems to be the only photographer to have captured this high-spirited display of nudity. “I can only presume that somehow my journalistic instincts were that this was about to happen,” he says. “Because it’s quite a way from where the festival site was.” As such, many curious civilians out for an afternoon stroll were also treated to the full-frontal fun. “That created a kind of contrast which was amusing,” he adds.

"I remember feeling that you were obliged to take your clothes of as well, you felt out of place if you didn't"

- David Hurn

“The whole atmosphere was one of relaxation,” says Hurn. Parents with babies and young children mingled with pop-loving teens. There was no violence, no fighting, people took drugs and had sex openly and the police were tolerantly indifferent. Hurn himself slept with no tent, under the stars. “It seemed to me incredibly human and enjoyable,” he says. “I really do like watching lots of people enjoy themselves. I’m a very ‘up’ person.”

This cheerful, affectionate atmosphere reflects the general mood in Britain at that time, says Hurn, whose iconic images of Beatle-mania or Welsh beach-goers are the most indelible of that era. “During the Sixties, I didn’t take assignments, I just went to things that interested me,” he remembers. “And in hindsight they turned out to be of historic interest.”

Legendary performances—including Bob Dylan, who had emerged from three years of seclusion to play in 1969 and Jimi Hendrix, whose show in 1970 would be his penultimate before his untimely death a month later—go some way in explaining why the festival has gathered near-mythical status. But Hurn, ever the champion of the everyday, believes it was the “strange and wonderful” sight of so many peaceful people enjoying themselves, that really made history.