When Music and Photography Collide

Folk musician and Magnum photographer Larry Towell lifts the lid on his versatile practice

In celebration of World Music Day, Larry Towell reflects on how his music and photography combine to offer a deeper understanding of the people and places he documents

Let’s start with your early musical influences.

I grew up as a country kid and we had a family band. In those days there was a difference between being raised in the country and being raised in town. Town kids were scary to me. There were eight of us brothers and sisters and we all played instruments. I played drums. Nobody took music lessons to speak of. But we played local weddings, dance halls, and occasionally in bars. There was a time in history when parents and their children played the same music and sang the same songs; it wasn’t until rock and roll in the 50’s that young people started to evolve outside of the music genres of their parents. I grew up singing the old country stuff– Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb, Patsy Cline. When I was 14, I quit the family band because it wasn’t cool. That’s when I started going to school in town and mixing with town kids. That was one of the biggest mistakes in my life, being influenced by my peers…. No wonder kids today are on medication and commit suicide due to social networking.

Did you go to college?

I went to art school and studied visual arts. We were poor, and in Canada in the 1960’s and 1970’s there was social assistance for kids from poor families so I went to university pretty much for free. After that, I travelled overseas to do volunteer work in India. That’s when I started to think about world distribution of wealth, rather than visual arts.

“River Song” from the album, The World From My Front Porch

What are your thoughts on the art world now?

I think the art world is just a type of conformity. You go to school. You get an MFA. You have a show. You get a dealer. After India, I built a raft, floated on the Sydenham River, and lived in solitude for a couple of years.

What was that like?

I learned to be alone. I also learned there’s nothing scarier than a blank piece of paper. I eventually met Ann and we got married and I needed some kind of job. I went to a local community college and told them I had an art degree and wanted to teach. They said they didn’t need anybody, but could I do anything else? Those were the days of night school, so I told them I could play guitar (but I wasn’t very good). They gave me a job [teaching guitar] starting in the fall. I went to a friend and asked him what I needed to know to teach adults night school and he said, “Very little”. He taught me some licks and I went from there. I did that for ten years. Mostly I talked and told jokes and sang.

How did you become a photographer from there?

I started travelling to Central America between semesters. Those were the Reagan years. U.S. president Ronald Reagan was attempting to turn the region into a smoldering landscape controlled by marauding death squads. I was writing poetry, recording testimonies, and taking pictures. I sent the pictures to Magnum on a whim. They must have liked the work. I didn’t know what I was getting into.

“The Earth Is Red” from the album, The Mennonites

So Magnum was instrumental in turning your career from this multi-disciplined practice to a focus on photography.

You know what happens in life, especially as a young person. You don’t know who you are. You open one door and it leads to another door. And that door leads to another door. Magnum made me into a professional door opener.

When you talk about poetry, music and photography, storytelling seems to be central . Do you find it easier to express creativity through music or photography, or perhaps they both offer completely different things?

They offer completely different things. To play music, you need to practice; you need to play and sing every day. With music you need the luxury of time and the luxury of solitude. So I need to go home. Near my pond I built a little cabin and that’s where I find solitude. That’s my ‘woodshed’.

Have you ever felt forced to categorize yourself?

Look… I’m a photographer. Most of my work is long term photo projects that manifest as books. But when I release a book I often release a music or poetry CD as well. I’ve also made a couple of short films. I think it was Tom Waits who said that if you have a business card you can’t put “Psychiatrist, Carpenter, Musician” on it, because people will think you can’t do anything right.

“No Man’s Land” from the album, The Dark Years: Chronicles of War

Photography is a visual medium. Music and lyrics aren’t visual, but they definitely offer a visual landscape. Do you think having that visual sense has helped create lyrics?

I don’t think so. It’s pretty different. Photography is illustrative; you’re a witness when you photograph. Whereas, as a lyricist, you’re depending on your imagination. They oppose each other. But I’m not at all a good musician. I’m a storyteller and experience as a photojournalist gives me lots of material.

How many instruments do you play?

I play a few… most of them badly.

But you record and do live performances, right?

I love the recording process. I also love working with great musicians. I have friends who I work with. Performing is another thing altogether. I do that very rarely because I can’t afford to travel with good musicians. I don’t have a market, and it’s a completely different discipline than recording or writing. It takes a lot of practice to sit in front of a crowd. When I do, it’s a multi-media show with images and field recordings in the background.

You once said you look for photographs that suggest what’s going on outside of the frame. Given that your photos and music are often born out of the same subject matter, can the same be said of the latter?

Photography’s greatest strength is its ability to illustrate, to be factual. But the most meaningful photography reminds you of something you’ve seen or experienced before, so it has an emotional attachment and it takes you outside of the frame in some way. It’s not just what you see, but how it makes you feel. It’s like poetry. Carl Sandberg once said something about the opening and closing of a door, making people guess what they saw behind that door.

“Refugee” from the album, Blood in the Soil

How do the CDs that accompany some of your reportage in, say, the Mennonite colonies or in East Jerusalem, bring an extra layer of understanding to the subject matter?

It’s not about understanding. It’s about feeling. I have a whole archive of field recordings, whether it’s with the Mennonites or in Afghanistan. And if I’m recording poetry or lyrics I’ll often use field recordings as a component of the audio track in the same way you might use piano or violin. I actually started recording Mennonites back when the first DAT recorder came out – so on The Mennonites CD you’ll hear recordings I made in the old colonies.

Your album, The Mennonites, is a rich tapestry that includes sound recordings, spoken word, ‘natural’ instruments and more…how do these complex songs offer a gateway to understanding this group of people?

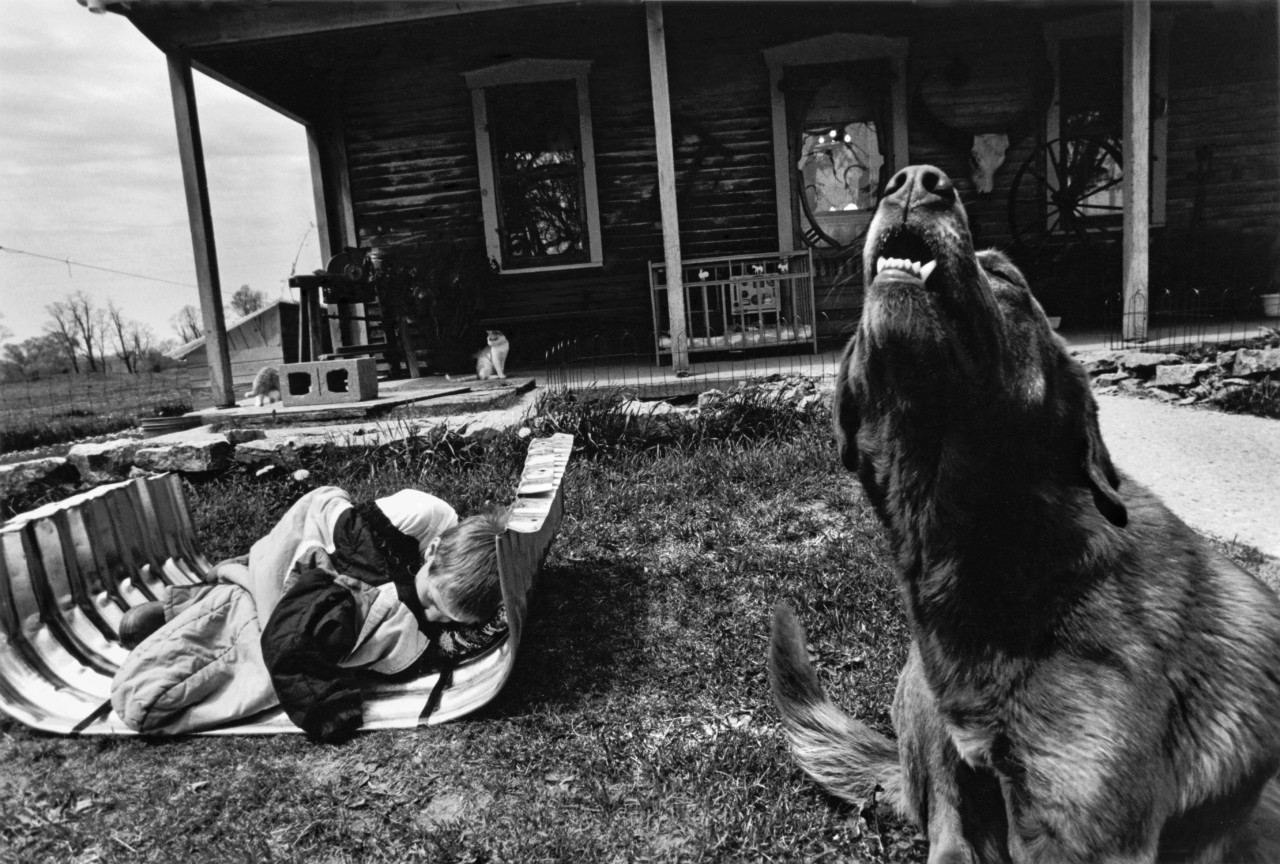

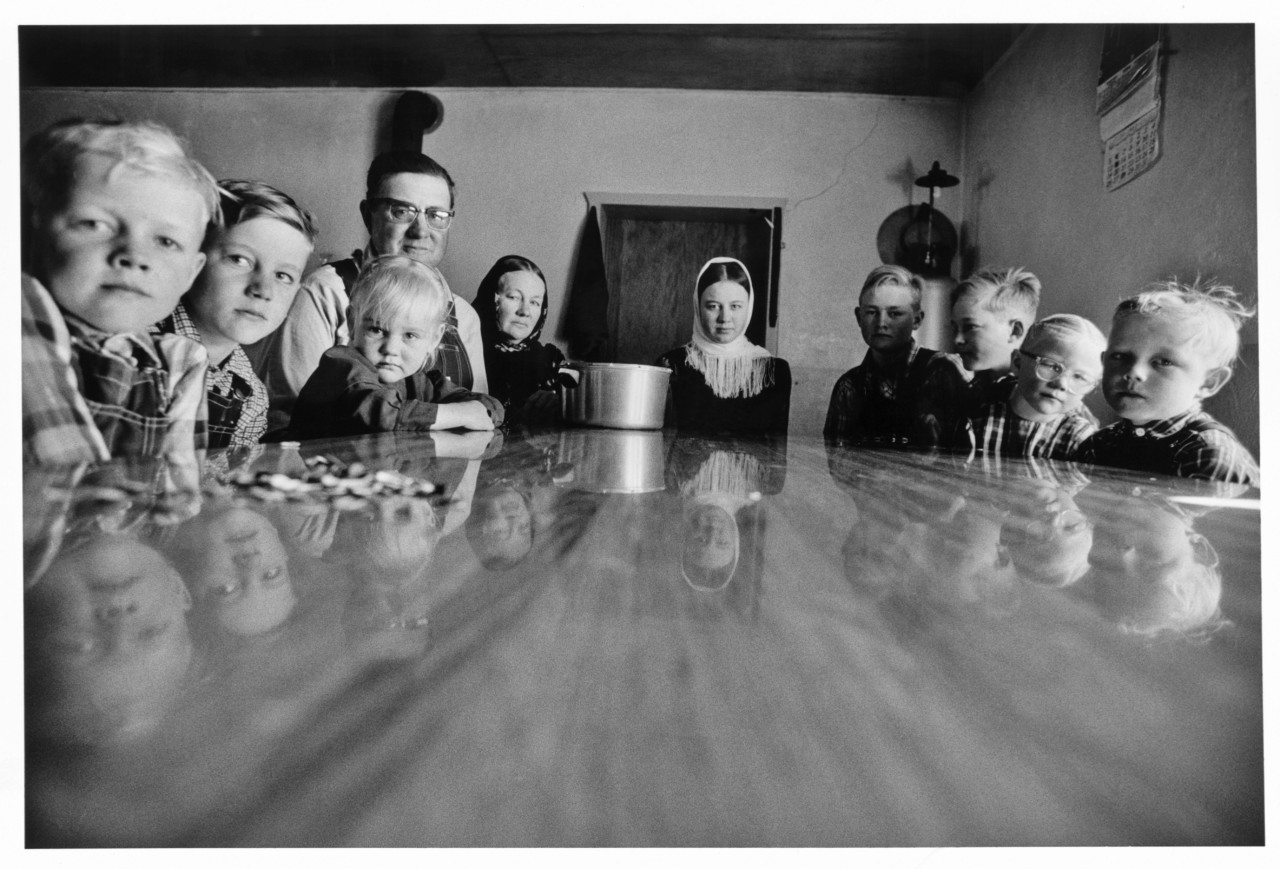

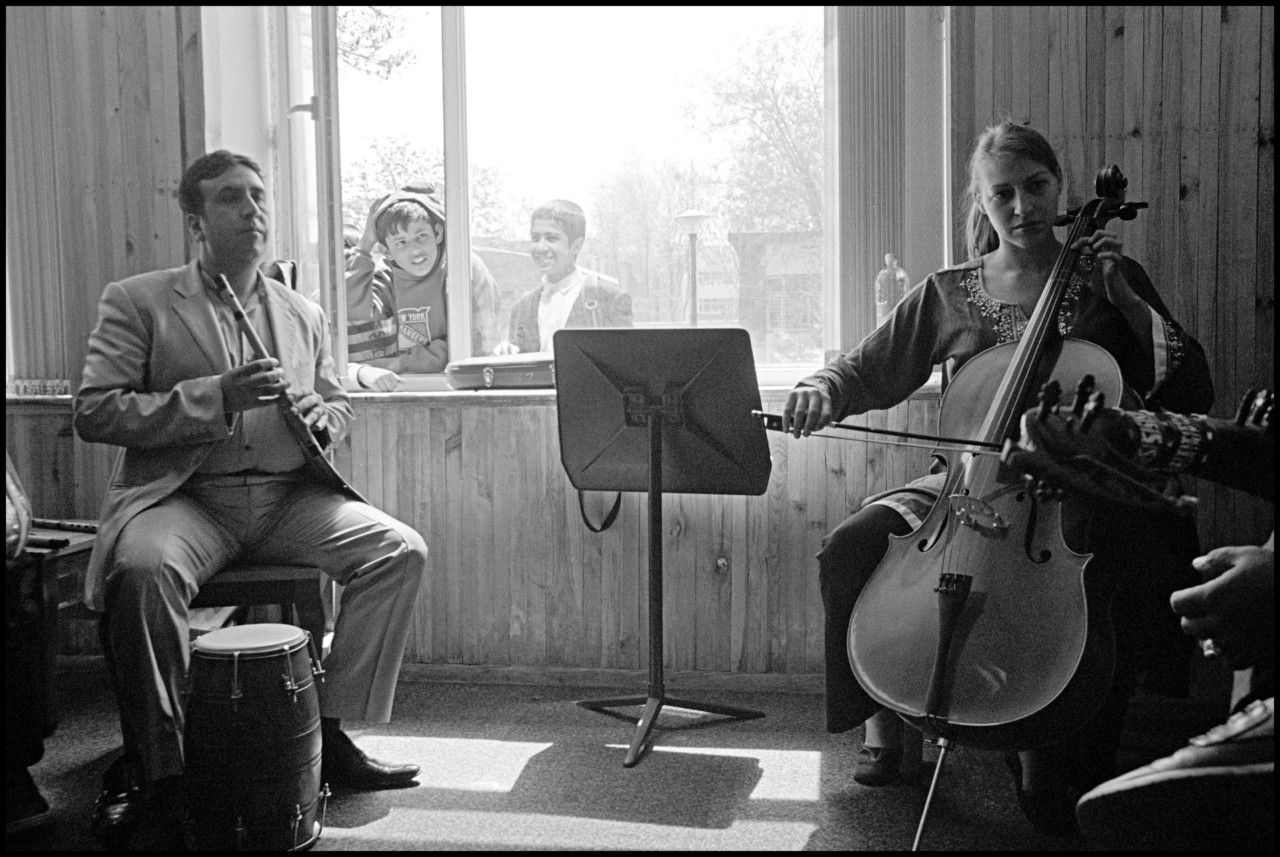

The sound makes you feel present. The Mennonites are a very reclusive group living in isolated colonies. They were forced to migrate to preserve their way of life. I got very attached to many families and followed them for ten years. As well as making photos, I also took notes on the small details of their everyday lives, and those details became relevant when I reflected upon them. I just hadn’t noticed them before I wrote them down. Then I brought a few of those vignettes into the recording studio and worked with Jeff Byrd, a musician friend of mine who plays with The Cowboy Junkies. We decided we wanted both classical music and field recordings to create a soundtrack for the book.

We would listen to the words and try to figure out what sounds they evoked. Sometimes it was the sound of wind or certain instrumentation and then we would experiment with the sounds and words and we’d add a guitar or the bones mixed with the sound of Mennonites singing around a lamp at the kitchen table, or the sound of wind, or dogs barking in the desert. It was an experimental process mixing things together. But it started with words and observations. It’s completely different than photographing. It’s like being blind. You don’t hear what you see. You see what you hear.

“Just Another Massacre” from the album, Blood in the Soil

And does this process differ when you’re working in conflict zones? Could you talk about the poem “No Man’s Land”, for example, and the process behind that?

In 2003, I’d gotten the Cartier-Bresson inaugural award to do a second book on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I’d already been working quite a bit in Gaza.

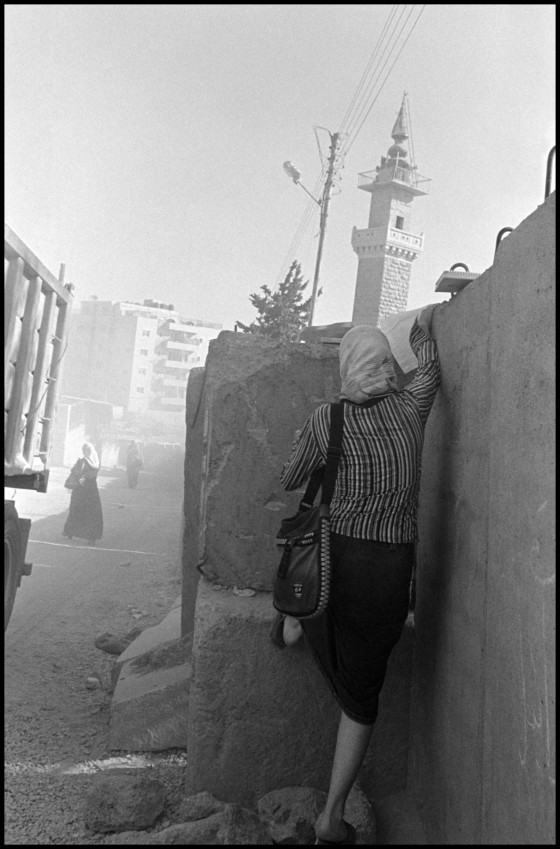

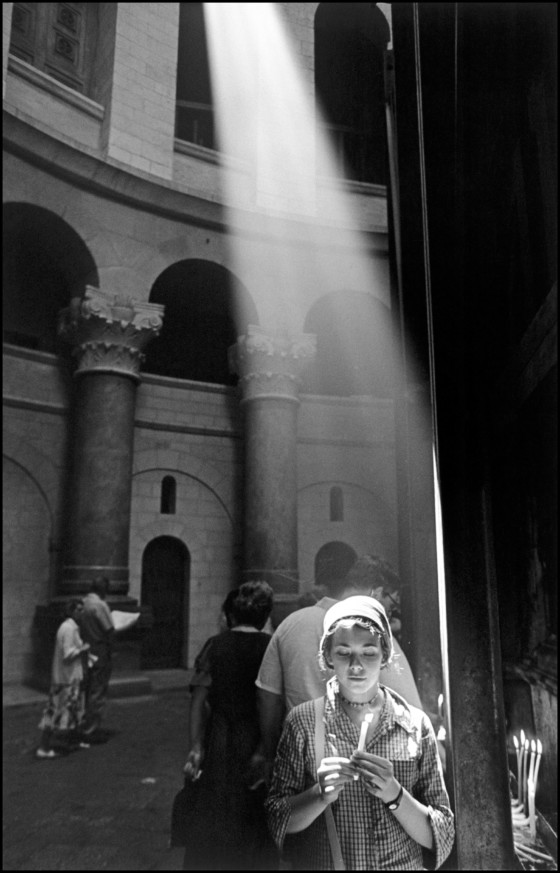

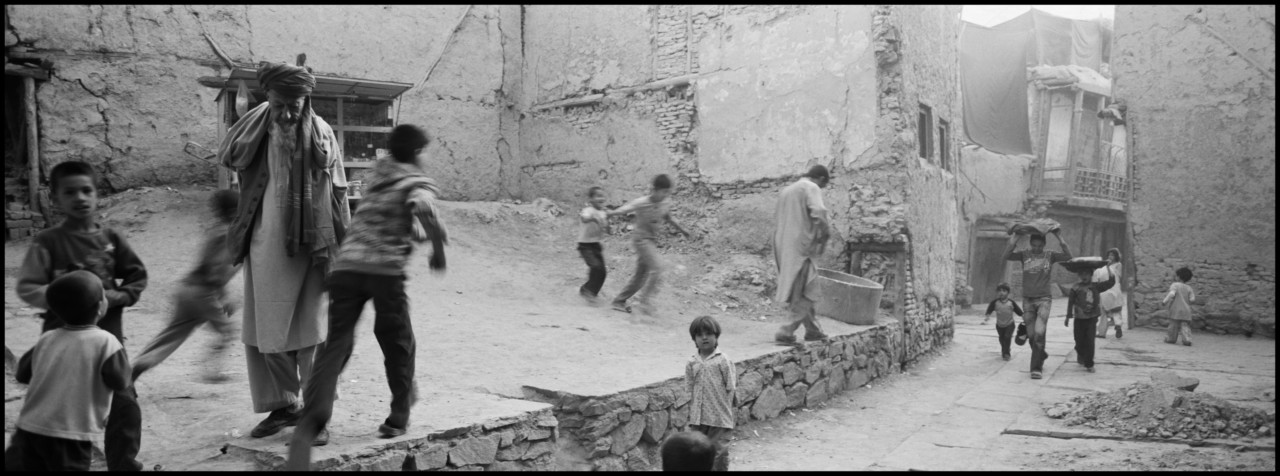

I was in occupied East Jerusalem and it was raining a lot on that trip. I would go out during the day, usually into the West Bank, where there might be a funeral [for someone killed] from the day before, during an Israeli invasion of a village. Sometimes, I would just go to Bethlehem and walk around and photograph. It was casual compared to Gaza. But because it was raining a lot, I would sit in my room and write. I wrote a series of pieces based on experiences of the day. The Palestine CD in The Dark Years compilation was written on one trip. I brought the poems into a recording studio and mixed field recordings with them, bringing musicians in as counterbalance. I worked with Scott Merritt in Guelph, Canada.

So the “No Man’s Land” poem is based on observations walking through the Arab Quarter of East Jerusalem one night. Is it a true story or is it not a true story? It’s a poem, so it brings you there in a non-illustrative way. I hear a cat, I hear footsteps, the echo of the old city. The star. The soldiers. Little observations become metaphors.

It completely comes from the experience of being there though.

Yes, and the reason I was there was because I was interested in conflict resolution. And of course the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the most challenging of all. I went back to continue examining, in particular, the life of Palestinians, who are probably the most humiliated people on earth.

Most of the issues I’ve dealt with have been issues of land and landlessness, whether it’s the Palestinians, Central American peasants, or First Nations communities in North America. We weren’t all made for other people’s empires.

Can you tell me about the song “Refugee”?

Listen to it. It’s a true story.

“The Man I Left Behind (Reprise)” from the album, Blood in the Soil

Do you write war songs?

Pete Seeger wrote war songs. He called them protest songs. “Just Another Massacre” is a protest song. So is “Refugee” and “The Man I Left Behind”.

How did the song “Just Another Massacre” come about?

That started as a couple of poems I wrote a long time ago after visiting a refugee camp in Nicaragua in 1984 of Salvadorans who’d fled the massacres in the 1970’s and 1980s. I created a chord pattern more recently and re-adapted some of those words to the chords.

Do sound and music have a role to play in your First Nations work?

We’ll see. I’m shooting video and recording sound, but we’ll see. I’m less comfortable putting myself in the mind of a First Nation person and telling a story because there is a strong movement for them to tell their own stories, so I’m very sensitive to that. But whenever my perspective enters in, yes, sure.

Do you have any heroes who are artists?

Federico Garcia Lorca, Spanish Civil War playwright, poet and musician once said: “The idea of art for art’s sake is something that would be cruel if it weren’t, fortunately, so ridiculous.” He was abducted and executed by Franco’s generals. He paid the price normally reserved for journalists.