Paolo Pellegrin on Documenting Family

Time spent in isolation in the mountains allowed the photographer to document a both deeply personal and momentous period

Paolo Pellegrin is perhaps best known for his photojournalism documenting war and its effects around the world, from Lebanon, Israel and Palestine, to the genocide in Kosovo, and conflict between Islamic State and Kurdish forces at Mosul. He has also focused on climate change, telling the story of the stark decline of the health of Antartic ice. The photographer here shares his notes on work of a different variety, reflecting on a period of introspection in which he turned his camera away from the immediate impacts of the pandemic and towards his family.

This text – along with a slection of Pellegrin’s images from the project – first appeared in The New York Times Magazine, in May of this year.

A selection of images from this work are available as fine prints on the Magnum Shop, here.

I was in Australia, working on a photographic project on the aftermath of the wildfires, and there was a moment when I realized that this pandemic was not being contained. It was spreading everywhere. My family was back in Switzerland, and I was playing these scenarios through my mind: Borders being closed. What if I get sick? What if I get stuck? What if my wife, Kathryn, gets sick, and I can’t reach her?

So we made a decision that we should all be together. I cut my trip to Australia short and rushed back home, just before they started imposing travel restrictions and closing borders.

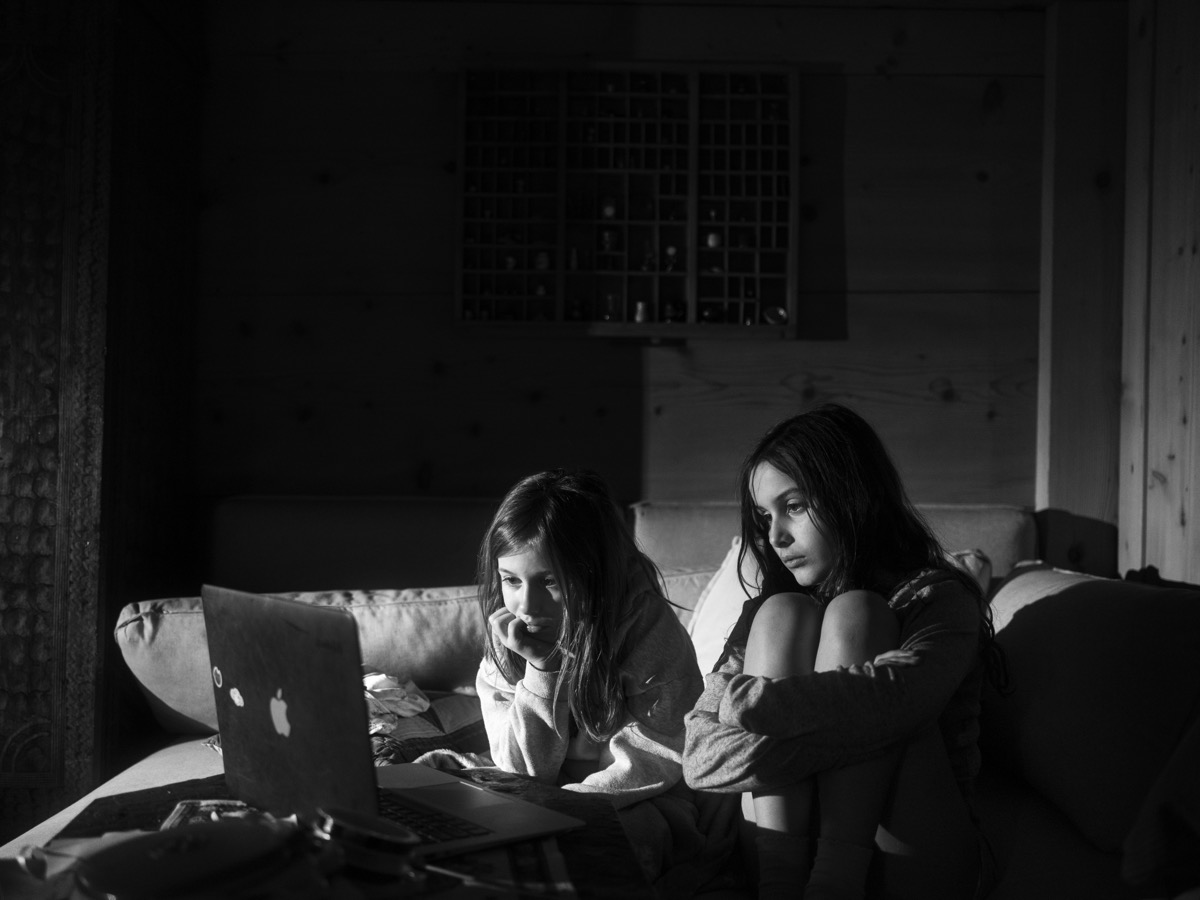

We live in Geneva in a pretty small apartment. The schools were already closed, and my wife and I realized it would be very hard for the girls, Luna and Emma, to quarantine there.

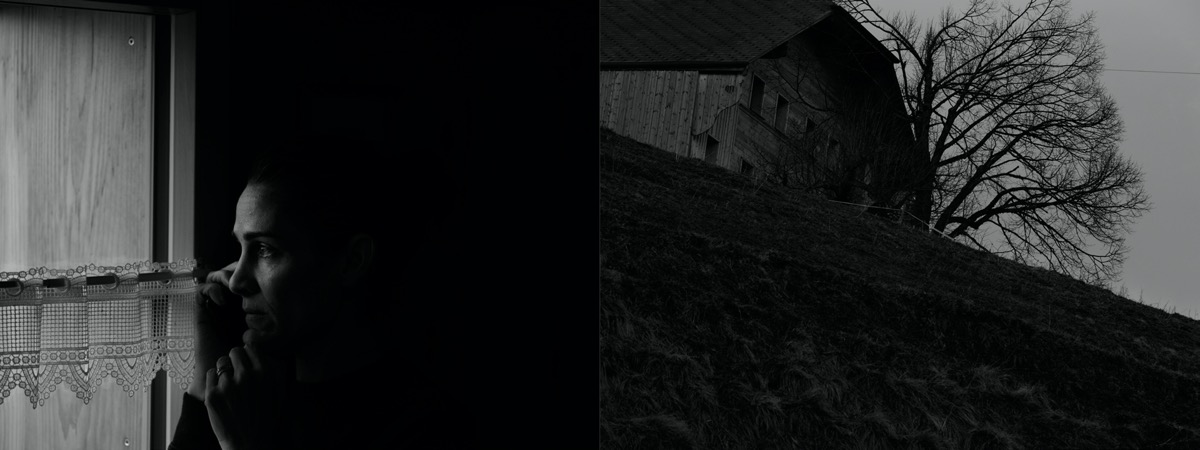

When we left the city for the mountains, I had the thought that we were going into the unknown with no horizon of what was going to happen or when it was going to end. I felt I wanted to document this experience, even just for ourselves, so I made a very deliberate decision to bring my ‘‘real’’ cameras.

We arrived at the farmhouse two days after my birthday, which is on March 11. We’ve been here now for more than two months.

Both my wife and I had a longing to be in nature, especially at a time like this. We’d been to this valley last summer and stayed in this place then. This is the countryside in Switzerland — when you get out of the city, it all looks like this. We’re pretty isolated in our little cabin. We’re very fortunate to all be here together.

I’m Italian, and in the first few weeks of the pandemic, seeing Northern Italy deteriorating very, very quickly, there was a sense of being in completely unexplored territory. That has parallels, surely, with the type of work I have done in the past as a photographer in conflict zones. Early on, it was our decision as a family for me not to travel, not to cover this. This is the first time in decades, maybe in my career, that I’ve decided not to cover an event, especially one of this magnitude.

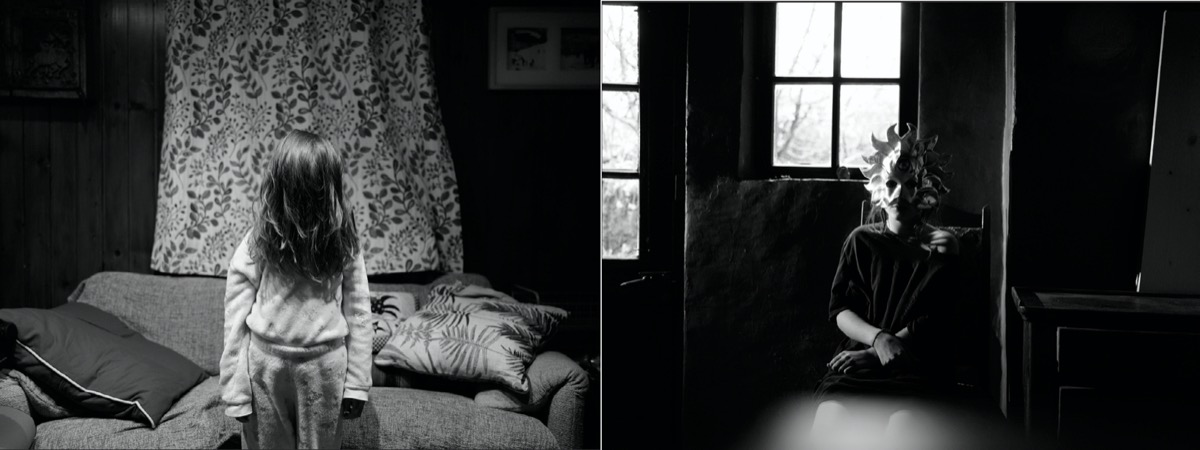

These photos are very different from my usual work. After decades of a certain type of photography, very kinetic and very dynamic, I have found myself looking for moments of silence. I’d never really photographed my family or the girls very seriously before. Yes, I’ve photographed them with an iPhone, as any other parent would. But I had a sense that I wanted to document this moment. This is the longest I’ve ever stayed with my family because I’m always traveling, always leaving, so to have this time together is very special. At the same time, I do not think of the pictures as a diary of a quarantine. Obviously there is that element, but I wanted to touch something that was more timeless and universal. Something about the girls, about the passage of time, about changes. Something that was in the moment but that also transcended it.

This text is shared as originally published on The New York Times, as told to Adam Sternbergh