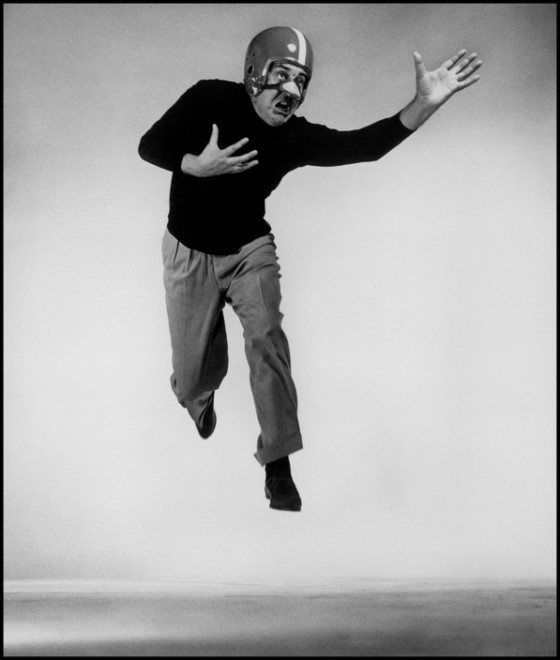

Philippe Halsman: Jump

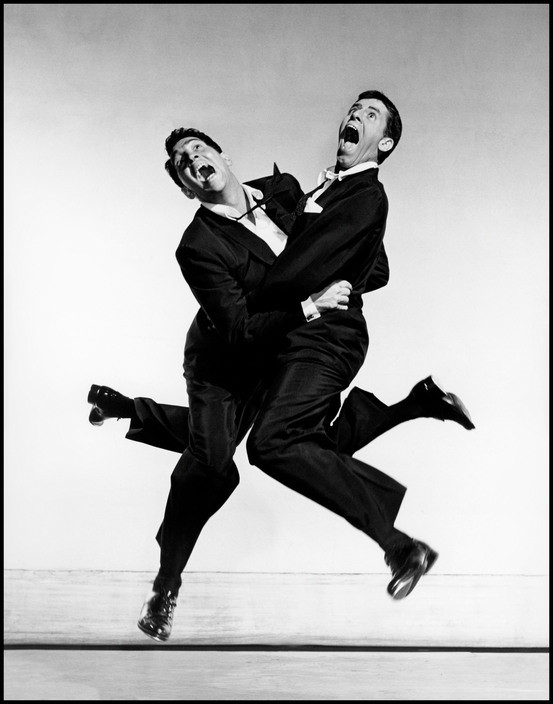

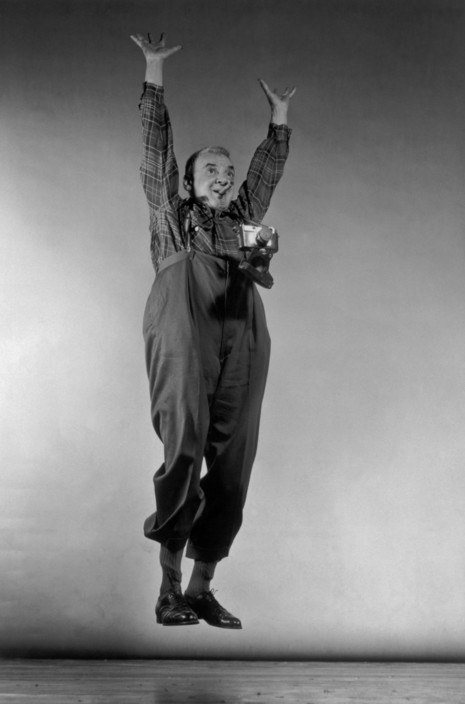

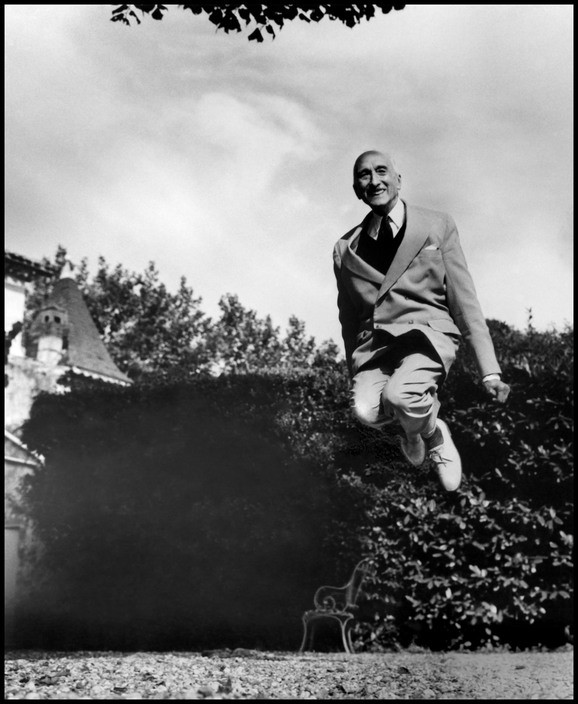

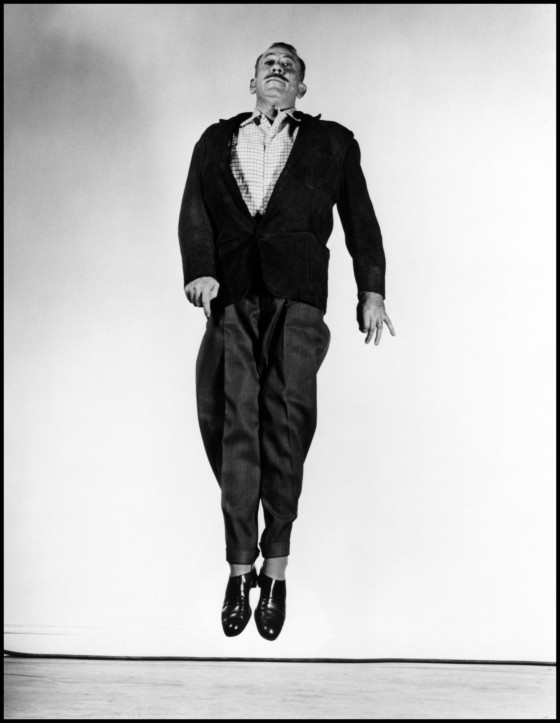

Philippe Halsman’s portraits of his most illustrious sitters jumping offer an insight into the hidden sides of their characters

“In a jump, the subject, in a sudden burst of energy, overcomes gravity. He cannot simultaneously control his expressions, his facial and his limb muscles. The mask falls. The real self becomes visible. One has only to snap it with the camera,” wrote Philippe Halsman. An acclaimed portrait photographer, with 101 Life Magazine covers to his name, over a period of six years Halsman asked all of his most famous and accomplished sitters to jump for his camera. He embraced the posture as an art form, finding that it opened up a whole new mode of portraiture. Through liberating his subjects from the conventions of traditional portrait photography, jumping also provided a way to gain insight into their psyche, and Halsman identified it as a new psychological tool, which he termed Jumpology.

"The mask falls. The real self becomes visible. One has only to snap it with the camera"

- Philippe Halsman

Fascinated by jumping since his childhood, Halsman was both a prolific and skilled jumper until a cracked iliac prevented him from engaging in the activity. His incorporation of jumping into his photographic practice began during a shoot of the Ford family to celebrate the company’s fiftieth birthday. The initial shoot went particularly badly, but, whilst having a drink with the family after, Halsman became overwhelmed by the desire to shoot Mrs. Edsel Ford jumping. The successive photographs saved the assignment and, from then on, Halsman asked every important sitter he photographed to jump.

Where many portrait photographers viewed their sitters’ internal worlds as readable through their faces, Halsman felt the opposite: “when we look at somebody’s face we don’t know what he thinks or feels. We don’t even know what he is like. Everybody wears an armor. Everybody hides behind a mask,” wrote Halsman in the accompanying text to his acclaimed Jump Book. Consisting of 191 black and white photographs of an array of his most famous and accomplished sitters jumping, the book also laid out the intricacies of Halsman’s discovery of this new psychological tool.

For Halsman, jumping was a device that could be employed to penetrate the masks of his sitters and expose their innermost secrets. Where Freudian psychoanalysis had the Interpretation of Dreams, Halsman developed The Interpretation of Jumps, in which he laid out the meaning of each element of this posture. “Often the photograph of a jump does not transmit its symbolic message immediately. A closer scrutiny will show, however, that every element in the jumper’s body – his arms, his legs, the position of the body, the expression of the face – reveals definite character traits,” he wrote. Indeed, for Halsman, every detail of this action possessed a meaningful and telling significance.

" Where Freudian psychoanalysis had the 'Interpretation of Dreams', Halsman developed 'The Interpretation of Jumps'"

-

From Marilyn Monroe, Grace Kelly and Brigette Bardot, to Richard Nixon and Salvador Dali, Halsman photographed an impressive number of illustrious sitters jumping. He interpreted each accordingly, both as indicative of the subject’s psyche and often also as emblematic of wider societal realities. Writing about the bent knees of Monroe, Kelly and Bardot while they jumped, Halsman observed that the childlike playfulness displayed by them exposed the fact that the overtly sexual image prescribed to these women was nothing but a reflection of the public’s own desires.

"Jumping humanity can be divided into two categories: one which tries to jump as high as possible and one which doesn’t care"

- Philippe Halsman

“Jumping humanity can be divided into two categories: one which tries to jump as high as possible and one which doesn’t care. The ones who try hard have ambition, drive and desire to impress others. The ones who don’t care either don’t take the jump seriously or lack ambition,” he wrote. In almost all of his portraits the subjects undoubtedly fall into the former, displaying a captivating array of jumping poses. Pictured leaping at his easel, enveloped by a flume of water and cats soaring through the air, his portrait of Salvador Dali is one of the most magnificent. Taken during the artist’s atomic period, in which he painted everything in suspension, Halsman recounts how it took 26 triple throws of cats, and 26 splashes of water to capture, in the 26th exposure, a still that satisfied the artist’s demands.

See more Classic Magnum stories here.