Reading: The Gratification of Watching Others Absorbed

To read is to exist in two places at once - and to observe others doing so offers a very particular sort of satisfaction

There has always been a certain kind of gratification found in watching other people read. Like many forms of watching that sit somewhere between voyeurism and matter-of-fact observation, it can be hard to define exactly why it’s enjoyable. Perhaps it’s purely a matter of nosiness: the kind of curiosity that’s been hard to satisfy in recent months, the chance to crane one’s neck at someone else’s book on the commute vanishing during lockdown along with other such prosaic pleasures as listening in on the next table’s conversation at a restaurant, or enjoying a bout of idle outfit-watching from a café window.

Maybe it’s a form of imaginative recognition too. Many of us know what it’s like to be wholly absorbed in a book or magazine, the world around us receding to a blur. Often (though not always, there being a hundred different reasons for itchily wishing to slide one’s eyes away from the page), to read is to exist in two places at once. No wonder books are often discussed in terms of transportation. No wonder, too, that in a year of unprecedented time spent indoors so many books have been cited as journey, escape, lesson or panacea. Reading lists – pandemic reading, plague reading, bath reading, joyful reading, adventurous reading, travel-without-leaving-your-sofa reading – have abounded, promising those with time on their hands the chance to exist, for a while, elsewhere.

"Many of us know what it's like to be wholly absorbed in a book or magazine, the world around us receding to a blur. Often (though not always, there being a hundred different reasons for itchily wishing to slide one’s eyes away from the page), to read is to exist in two places at once"

-

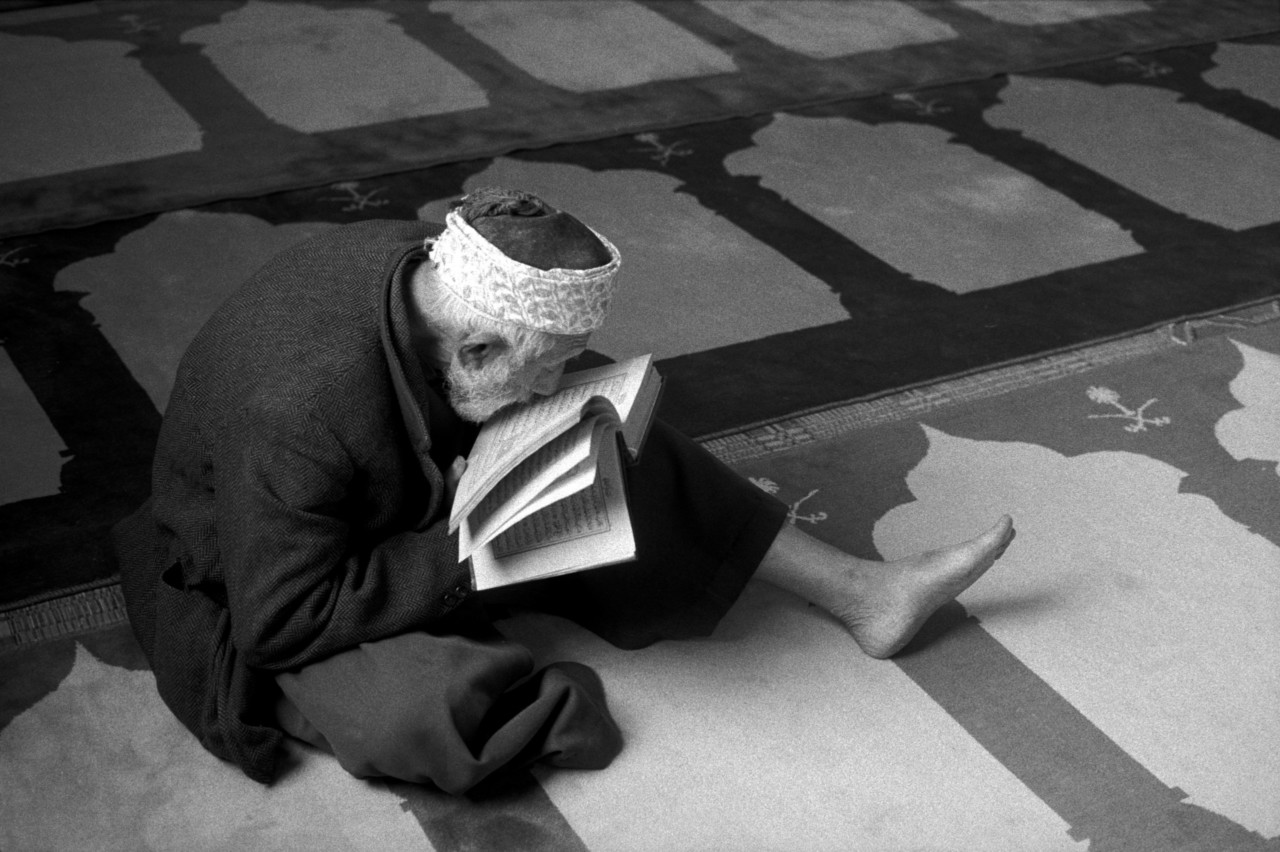

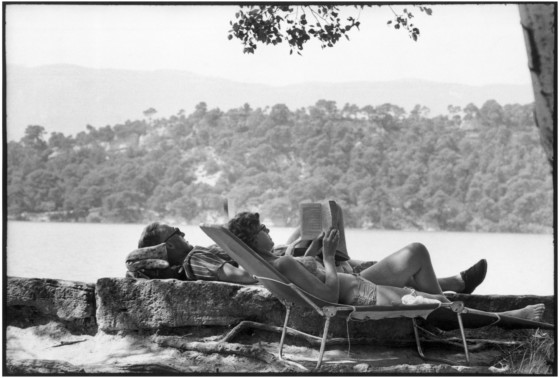

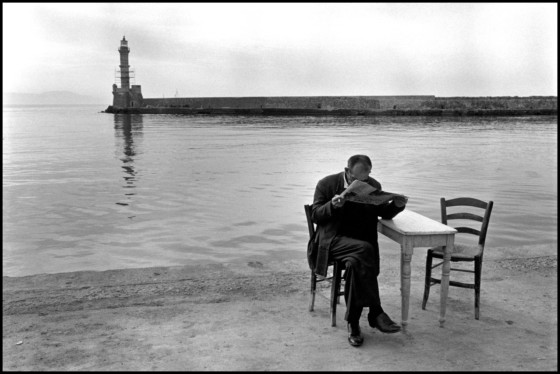

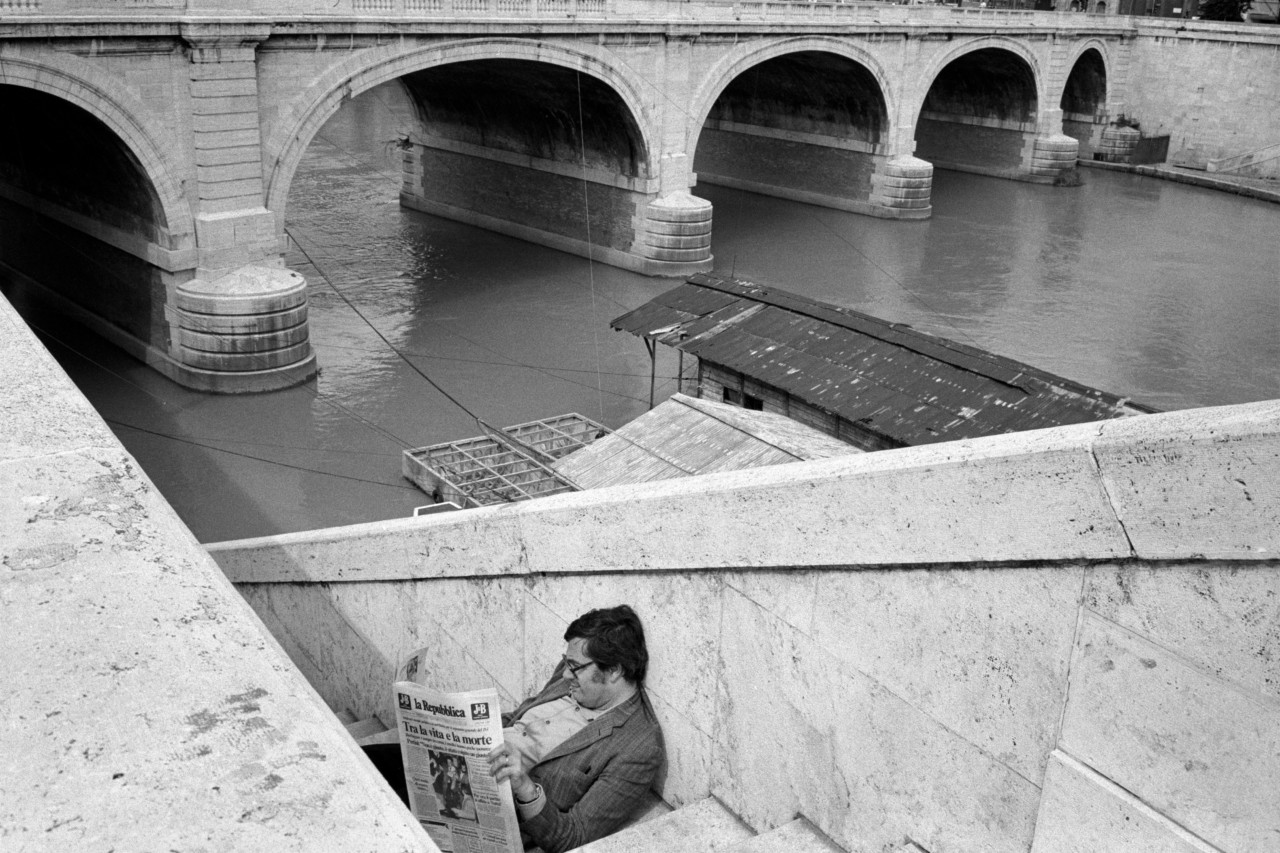

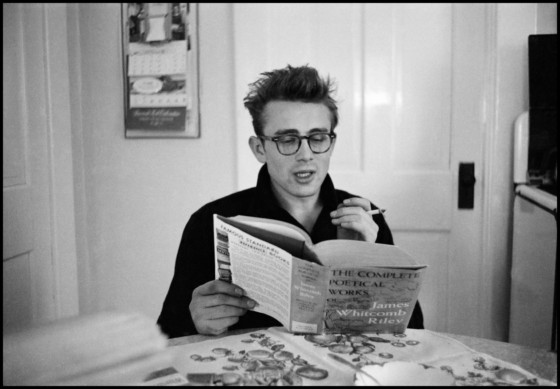

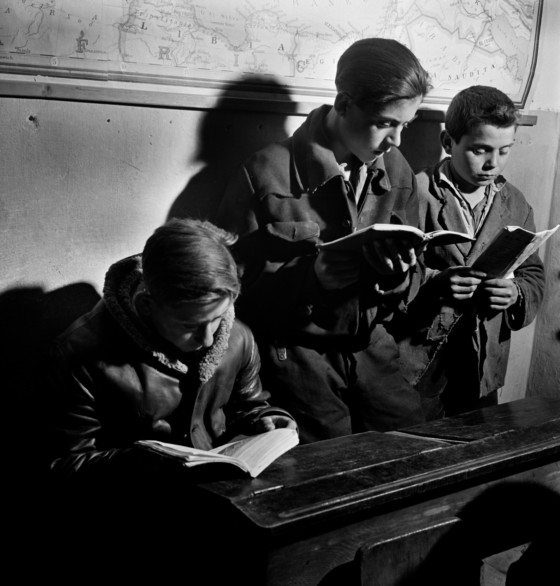

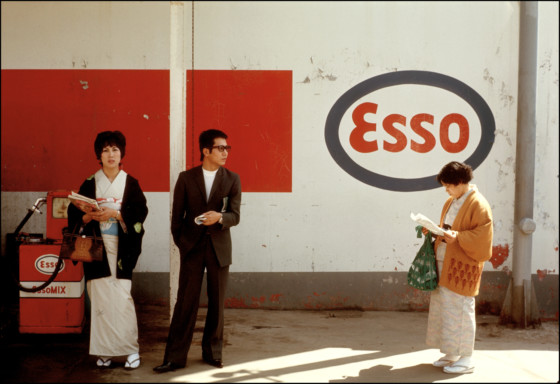

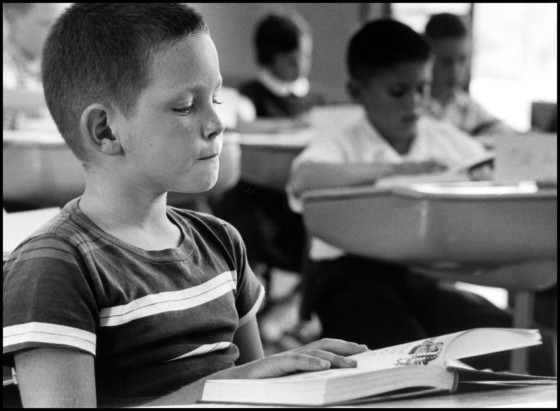

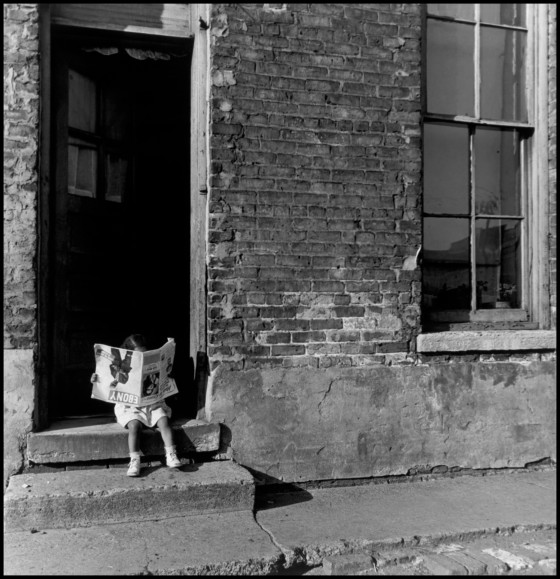

Magnum’s archives are rife with photos of people reading. They sprawl with books, curl up with magazines, and run their fingers over holy texts. Just as it’s enjoyable to watch people read, it’s also pleasingly intriguing to look at photos of people reading. Here many of the same principles and pleasures apply. The voyeurism, if anything, is more pronounced. No matter how long we look at the image, the one(s) reading can’t glance up at the page and inadvertently catch us looking. Curiosity is amped up too. Here is a chance to glean numerous details and clues: to read the photo, if you will, or at least engage in a rewarding act of interpretation as sparse surroundings or a yellow dress billowing on a subway platform tell a brief, silent narrative.

"Each of these photos simultaneously stands alone - a singular story of a singular experience - and sits alongside its fellow images, creating an entire gallery of readers united only by their interest in the pages in front of them"

-

Each of these photos simultaneously stands alone – a singular story of a singular experience – and sits alongside its fellow images, creating an entire gallery of readers united only by their interest in the pages in front of them. Photography, especially of the documentary variety, is curious like that. In alighting on certain themes and moments, it suggests that, ultimately, all the infinite facets and possibilities of human activity can potentially be categorized and sat alongside each other. It’s an idea taken up by Geoff Dyer in The Ongoing Moment, Dyer’s attempts to view photographs through a series of “organizing principle[s] or node[s]” letting the author flit around from benches to hats to buskers. Each photo becomes a thread, connecting it to numerous other motifs, shapes, objects, and moments in time. Sometimes the links are predictable. At others, they are wonderfully unexpected.

"In the case of photographs of people reading, one strongly feels this drive towards indexation. It’s not just a desire to group such images together in the first place, but also to create countless, specific subcategories"

-

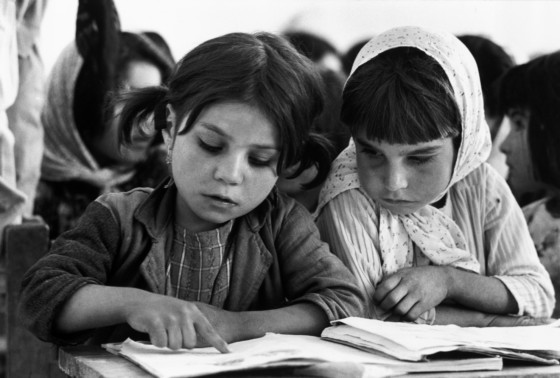

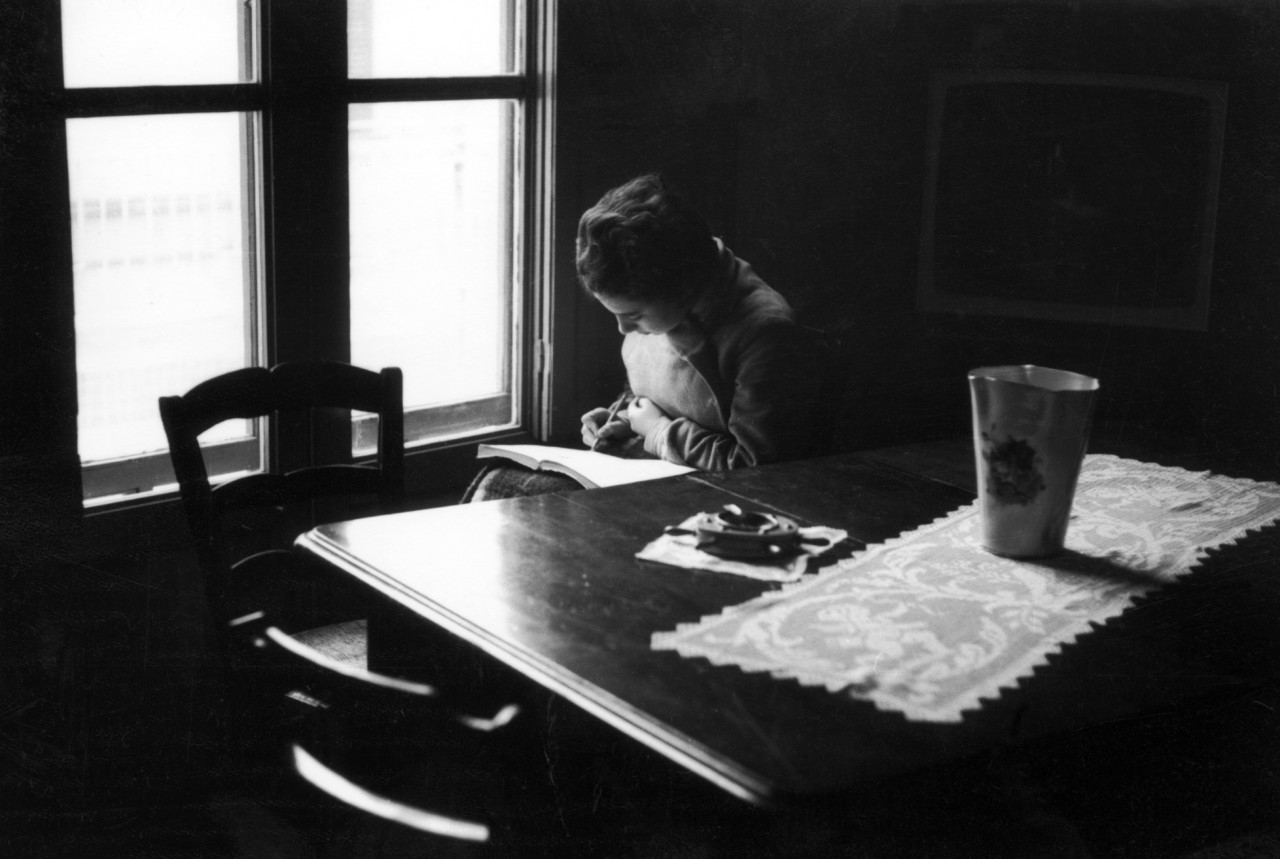

In the case of photographs of people reading, one strongly feels this drive towards indexation. It’s not just a desire to group such images together in the first place, but also to create countless, specific subcategories. For example, if one were to try and break down the main types of reading documented within Magnum’s archives, it might include some of the following. Beach reading, accompanied by garish swimsuits and candy-striped windbreakers. Religious reading, both alone (on beds, in pews, wandering through fields of flowers) and with others. Students working diligently at their desks. Fidgety children being read aloud to. Rapt children lost in their own imaginative worlds. Newspapers perused in cars, outside restaurants, at café tables. Books in transit, read to pass the time on trains and planes. Friends and lovers looking at the same page. Solitary readers catching a moment on a park bench or canal side.

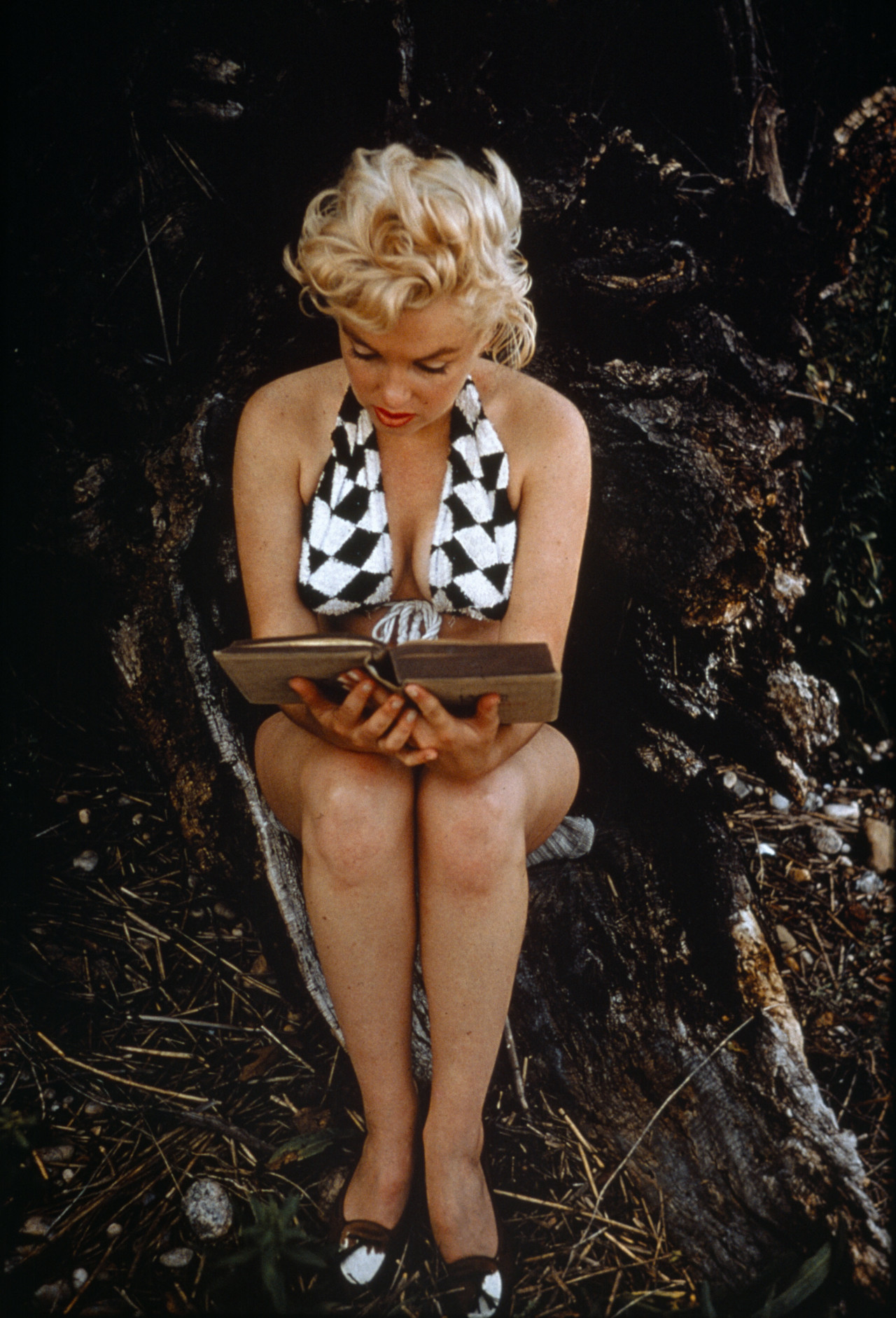

One detail unites them though. Whether bronzed sun-seeker, pilgrim, or schoolgirl, these are all photos in which the subject’s gaze lies elsewhere. All that voyeurism and curiosity is largely possible because the readers’ eyes remain on the page. In being transported, in being both there and not there, the reader presents the perfect distracted opportunity for the camera. That is not to rule out the reader’s awareness of the lens. Some of these photos, such as Eve Arnold’s famous photos of Marilyn Monroe absorbed in Ulysses, figure as intimate portraits in which the reader is undoubtedly aware of being observed. Others figure more like snatched glances, cannily caught as the photographer strolls through the city or beside the seashore.

"These photos too involve that knowledge of unreciprocated observation: the awareness that one is witnessing an activity with some private component that remains inaccessible to outside eyes"

-

Few photographers in Magnum’s archives have spent more time dwelling on people reading than Steve McCurry. Producing a book titled On Reading in 2016, the photographer paid homage to another great photographer of readers: André Kertész. The Hungarian photographer returned again and again to the craned necks and bent knees of those absorbed in books and papers. His photos were crisply monochrome, illustrative, as Blake Morrison wrote in The Guardian, of the quotidian realities of reading: “When paintings and sculptures depict a man or woman with a book, this usually signifies that they are studious, saintly, noble and wise – persons of substance… Kertész’s subjects are often people you wouldn’t expect to see reading. What the camera captures is their thirst for knowledge or hunger to escape their circumstances.” Although we are now far away from the realm of expecting a book to figure in an image solely as a status symbol or object of learnedness, McCurry too offers up a plurality of readers: this experience here caught in vivid colour, whether via a backdrop of flames at a steelworks or through the faded shutters of an open window.

"Through such photos we too can be transported to the scene of the reader, but the experience of reading remains entirely theirs – always unknowable to those who look on"

-

These photos too involve that knowledge of unreciprocated observation: the awareness that one is witnessing an activity with some private component that remains inaccessible to outside eyes. They suggest pause, stillness, absorption. Through such photos we too can be transported to the scene of the reader, but the experience of reading remains entirely theirs – always unknowable to those who look on.