Magnum photographer Abbas, who died in Paris on April 25, 2018, traveled the world documenting religions and revolution. But one week before his death, the man who described himself as a “historian of the present,” spoke to Magnum Photos about his interest in something rather different: the newspaper business.

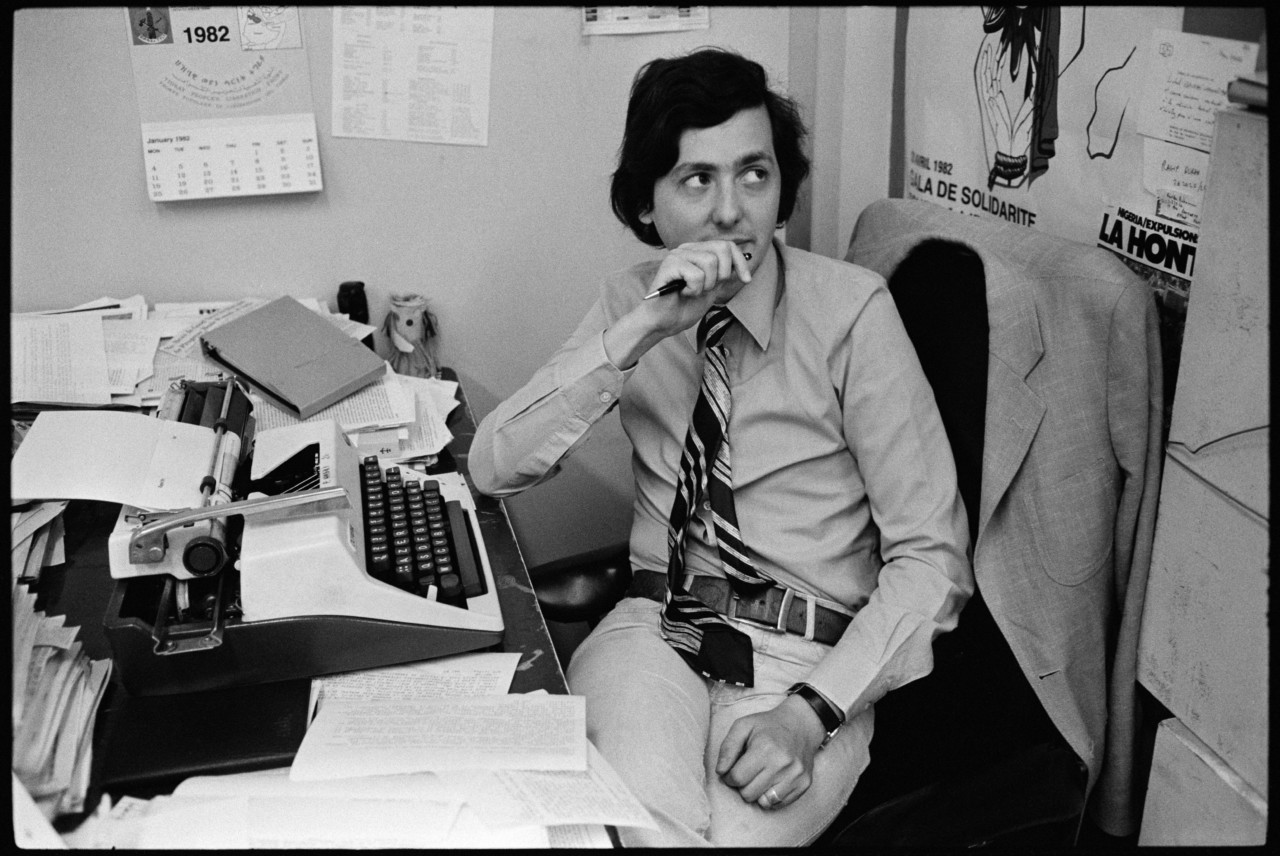

In 1983, Abbas photographed the editorial offices of the left-wing newspaper Libération, founded a decade earlier by French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. He returned after 35 years, this February, to see how the place had transformed. The changes go beyond the shift from typewriter to computer—extending into the political sphere. Libération traditionally served the far-left, with a motto of “People, take the right to speak and keep it.” Since then, Libé, as it is affectionately known among its core readership, has moved closer to the political center and is broadly considered center-left today.

Libération emerged out of the legendary May 1968 student protests and quickly became a leading anti-establishment voice. Founded by Sartre and Serge July in Paris in 1973, the paper was extraordinarily influential in its early years, despite its circulation never exceeding 200,000. Sartre and July, former members of a Maoist group, were dedicated to making Libé a publication that gave a voice to the people. In an interview at the time, Sartre said Libération wouldn’t take a party line. “Parties talk about the masses. What we want is for the masses themselves to talk.”

The newspaper initially refused to take paid advertising and was co-owned by all the staff. All employees received the same salary—minimum wage—and there was little hierarchy; important decisions were voted on. This eventually became unsustainable. In 1981, July, who had taken over as editor from Sartre in 1974, suspended publication and relaunched after a few months. Paid adverts were introduced the following year, but it retained its non-conformist atmosphere.

“In 1983, it was post-hippie—there were lots of people with long hair. It was fun, very relaxed. You felt you were among friends,” Abbas said, speaking over the phone from his home in Paris.

Now, the offices of Libération are more formal. “When I first went into Libération this year, I saw the round conference table and it says a lot. It’s like a ministry, rather than a newspaper. It was very organized,” he said. “It’s still very much open, but it was much more business-like than it used to be.”

"In 1983, it was post-hippie—there were lots of people with long hair. It was fun, very relaxed. You felt you were among friends"

- Abbas

Abbas attributed the change to the natural evolution of companies since then, but also the change in ownership—which has been controversial. In 2005, after a major fall in circulation, businessman Édouard de Rothschild took a 38.6% stake in the paper. The following year, July was forced out and many others resigned.

In recent years, Libération has had some memorable front pages, particularly after the election of President François Hollande and the Charlie Hebdo attack. In 2008, it launched a sub-brand Désintox, dedicated to fact-checking and interrogating claims by politicians. But like so many other media outlets, the move to digital posed a real challenge to Libération and readership plummeted.

The paper has continued to struggle through financial crises. In 2014, the front page of its weekend edition didn’t show an investigation or a feature article, but a full-page denunciation of a plan by the paper’s shareholders to turn the Paris headquarters into a conference venue and cultural center. “Nous sommes un journal” (We are a newspaper), the headline read, followed by a list of everything Libé was not—not a restaurant, not a TV studio, not a startup incubator, and so on. Inside, an editorial informed readers why staff had gone on strike and said the shareholders’ plan would “reduce Libération to a mere brand.” The editor-in-chief Nicolas Demorand resigned.

Today, Laurent Joffrin is the editor of Libération. Abbas said the newsroom is similar today in that the employees are still relatively young, but he pointed out that the photographs show there are more women now than back then, particularly in higher positions.

In one respect though, this year’s visit was the same as in 1983: Abbas was able to go about his work as if he wasn’t there. “They ignored me, which is a good thing. They would answer my queries and be welcoming,” he said. “But they had a job to do—and so did I.”