Bruce Davidson’s East 100th Street: Harlem, 50 Years On

Following the end of Harlem Week—a month-long celebration of the neighborhood’s unique flavour—Davidson’s seminal work on East 100th Street is remembered

Harlem has long been a paradigm of both the suffering and soaring achievements of New York’s underprivileged communities. Though poverty and oppression have gnarled its streets, it was here the Civil Rights Movement took shape and the Renaissance of African American culture exploded; small stories and big ideas that shook and shaped American identity.

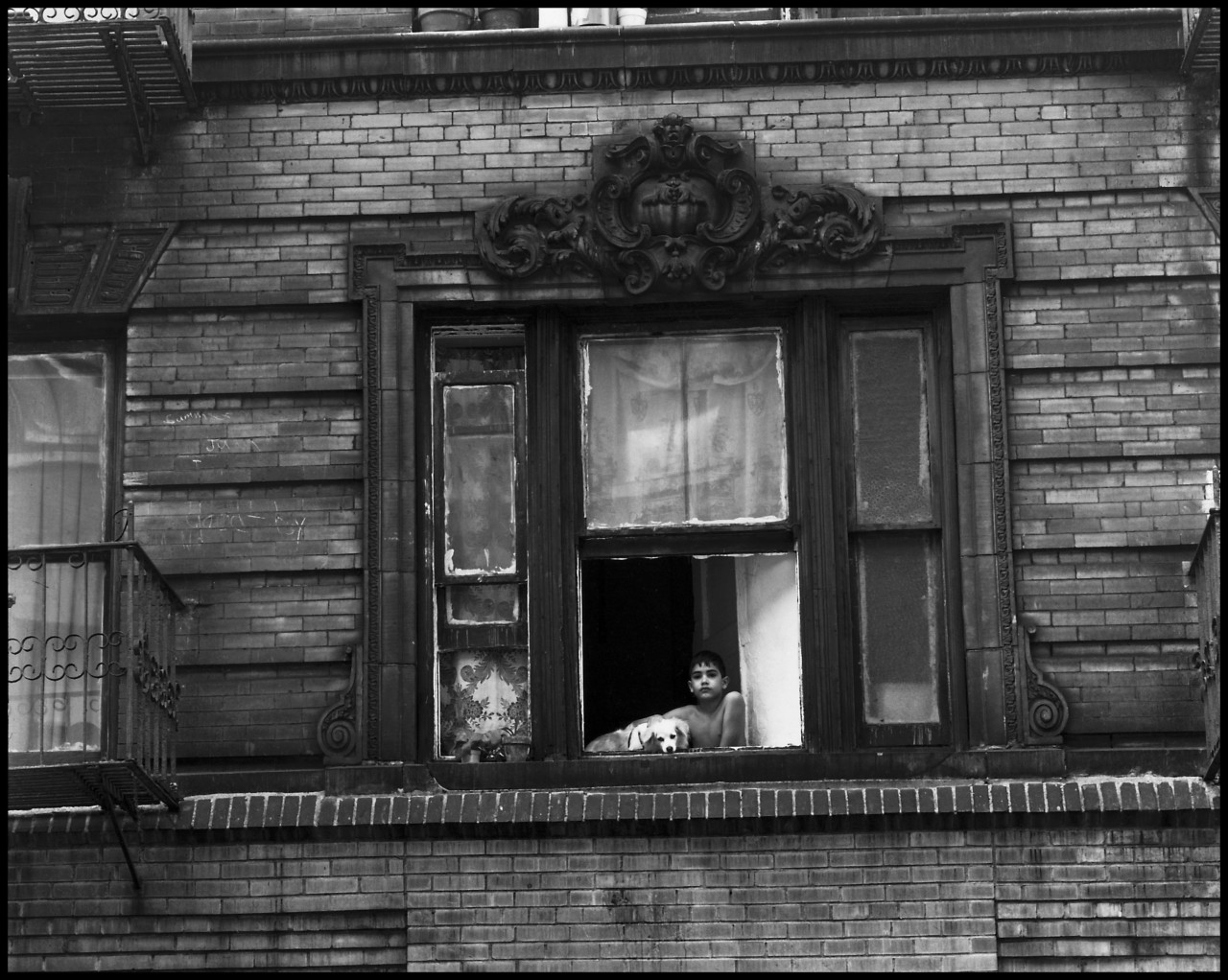

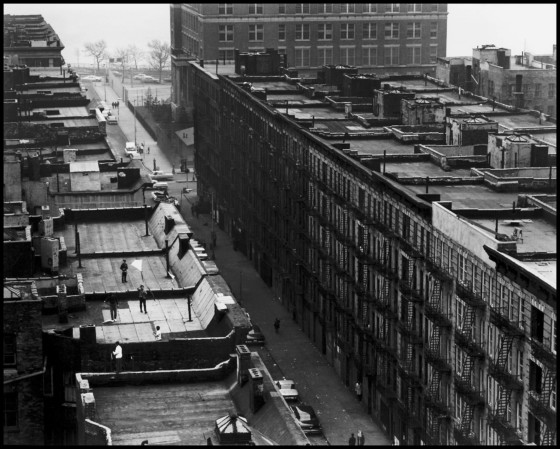

Photographer Bruce Davidson, an Illinois native living in Westchester at the time, first caught a glimpse of that world when riding a commuter train from Hartsdale to New York City in the early 50s. Through his carriage window he saw straight into the rooms of a row of East Harlem dwellings, and caught a glimpse of the lives of their inhabitants. “Even then I wanted to get behind those walls and to encounter the invisible,” he said. “More than a decade would pass before I entered those hidden worlds with my camera.”

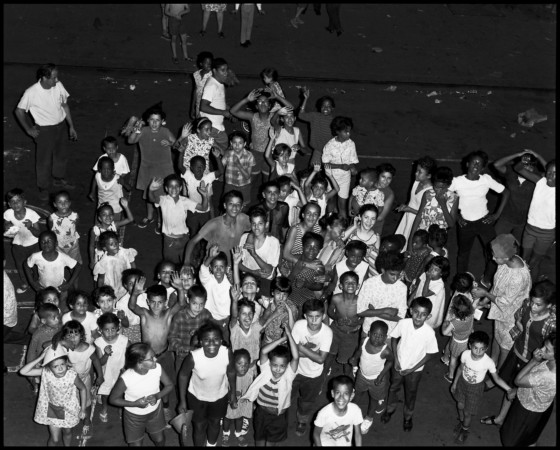

After receiving a grant from the US National Endowment for the Arts, Davidson photographed one Harlem street, East 100th, between 1966 and 1968. His primary intention was to improve the housing situation for its residents, many of whom were living in crumbling tenement buildings. Though initially met with distrust—many photojournalists had come before him to get easy snaps of ‘poverty porn’—Davidson knew he had to stay around a while and earn his dues. He got an ‘in’ through the Metro North Citizen’s Committee, who granted him permission to photograph if he agreed to present his images for review.

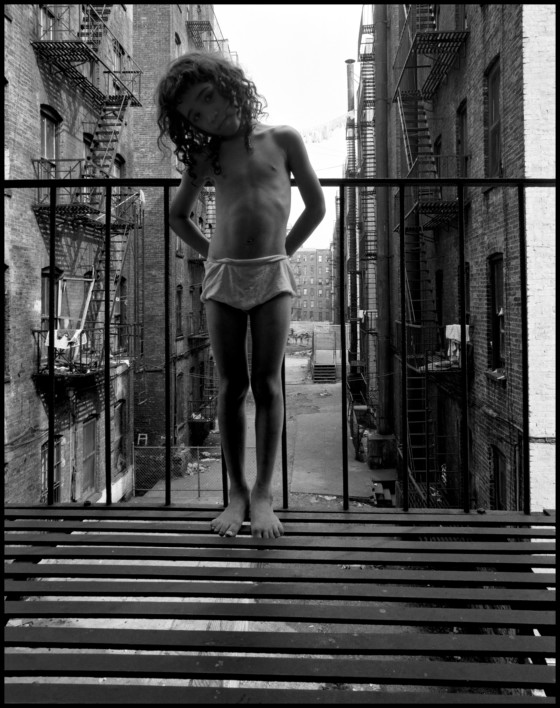

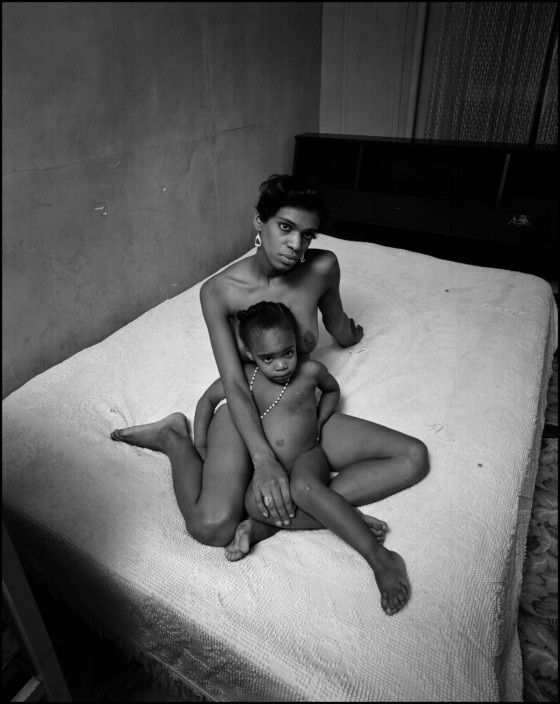

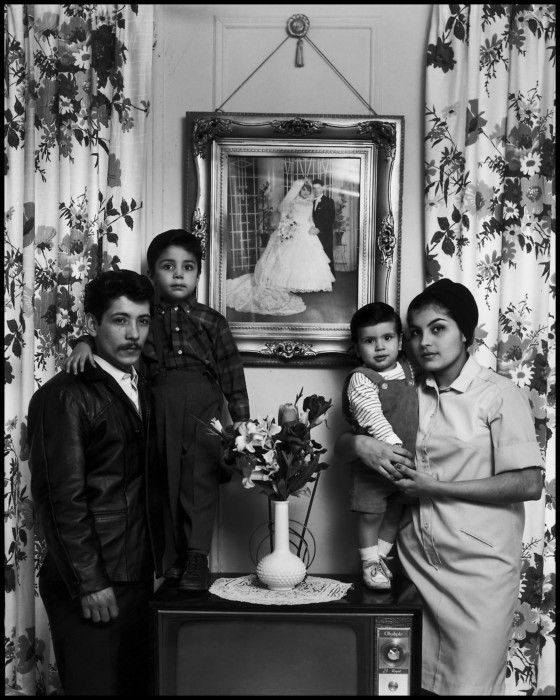

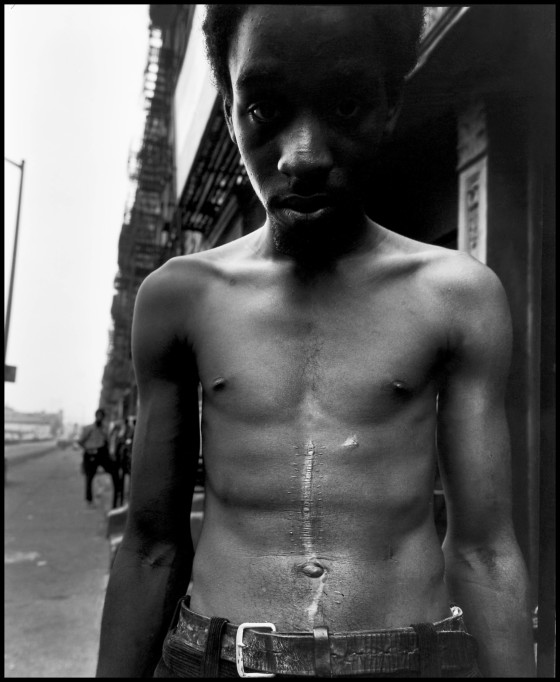

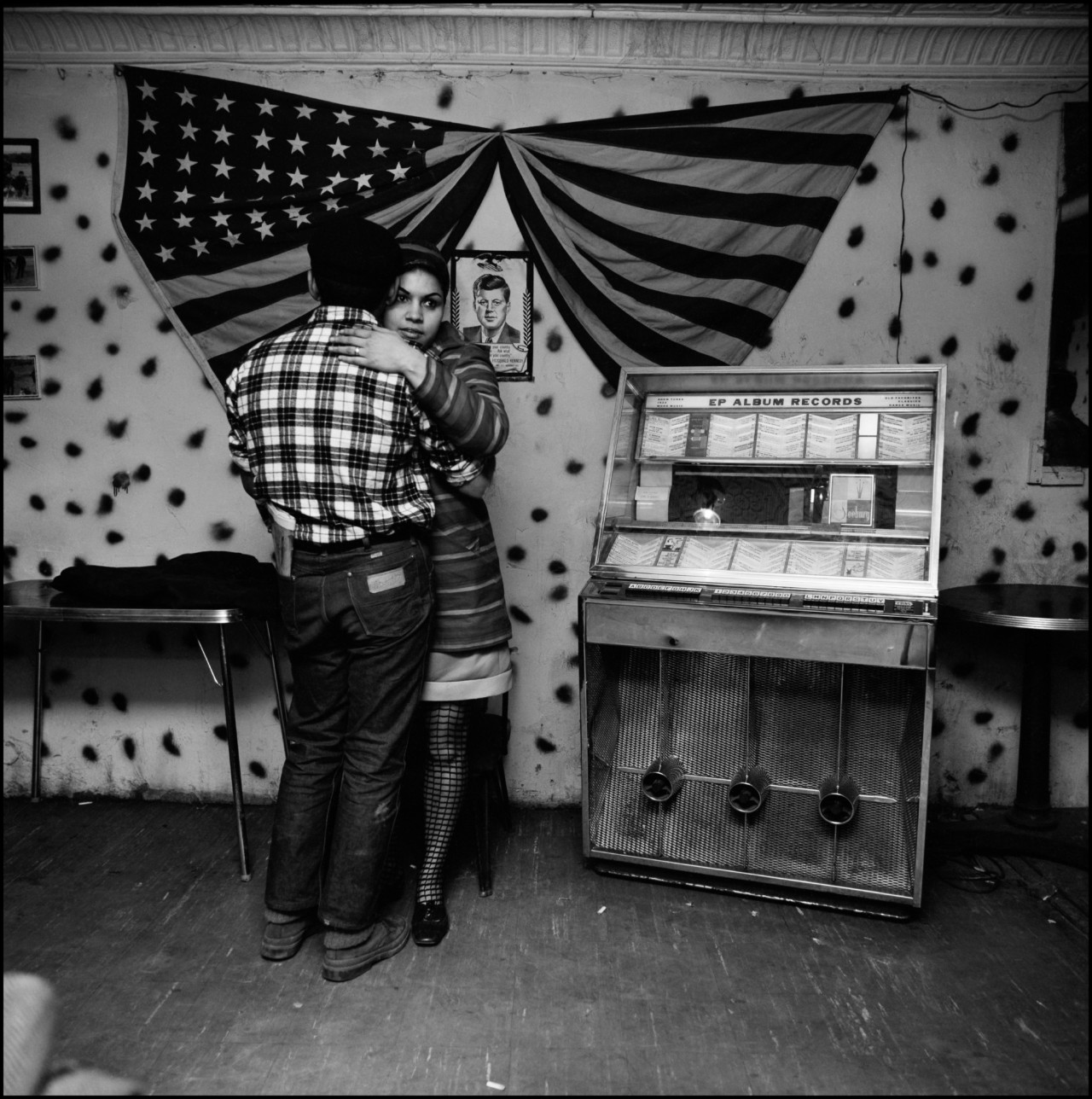

Davidson got closer and stayed longer, refusing a telephoto lens in favour of a formal, collaborative process. “The presence of a large format camera on a tripod, with its bellows and black focusing cloth, gave a sense of dignity to the act of taking pictures,” he said. “I didn’t want to be the unobserved observer. I wanted to be with my subjects face to face.”

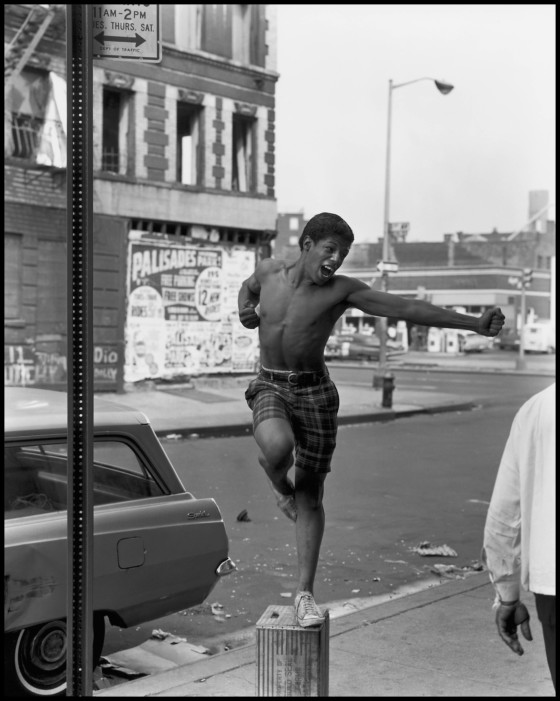

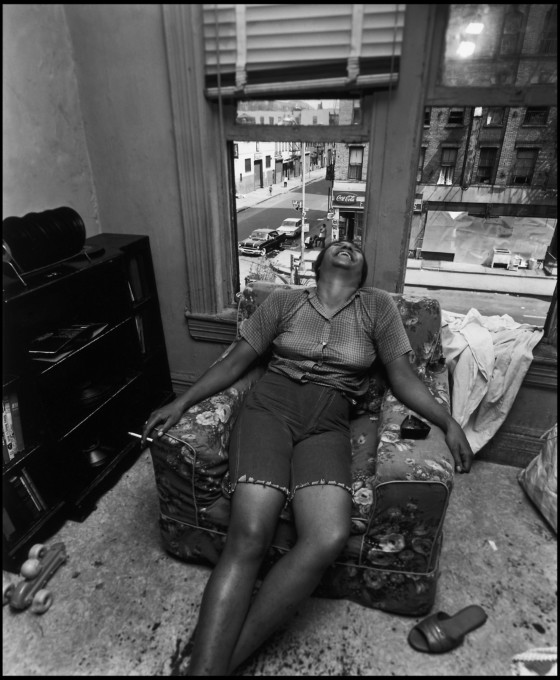

He succeeded. The intimacy and mutual respect between photographer and subject is an essential part of this classic essay and indicative of Davidson’s moral vision. The subjects are almost always looking at the camera; challenging the viewer to hold their gaze and consider their desperate circumstances. Some photographs shout to be heard; a young boy playing alone in an alleyway of rubbish or an elderly woman crouched on the dirty sidewalk. Others are quietly poignant; a row of freshly pressed white shirts hanging in a house half collapsed or three young girls proudly dressed in their Sunday best. Others still are tender, playful, romantic and lucidly human.

"I didn’t want to be the unobserved observer. I wanted to be with my subjects face to face"

- Bruce Davidson

When East 100th Street was published in 1970, it divided opinion among critics, some claiming Davidson made Harlem look ‘too bad’, others saying he didn’t make it look bad enough. But, according to Mildred Feliciano, an activist and Harlem old timer whom Davidson photographed, the pictures rumbled the people that mattered; politicians and bankers who had the power to create positive change. “I took East 100th Street with me to city agencies. I showed them the way we were living and what we needed,” said Feliciano. “Bruce’s pictures carried the message to our government and city agencies of how poor people lived. These photos are not only historical but helped in the rebuilding of our community.”

Fifty years after the last pictures were taken, as the 44th Harlem Week celebrations have drawn to a close, the neighbourhood is experiencing a different kind of revival. While the 1920’s saw a cultural and literary revolution, now it is cultural preservation, gentrification and economic development that are preoccupying the storied streets of Upper Manhattan. As the heartbeat of old Harlem grows quieter, Davidson’s pictures, though specific to a particular street in a particular moment in history, captured a “mood” that is timeless.