The Black Country in Close Up

In 2013, Bruce Gilden was commissioned to make street portraits in the West Midlands. Now, Setanta has turned his photographs into an eye-popping photobook

“I always liked sports, and I always rooted for the underdog,” says Bruce Gilden, speaking to camera in a short film made in 2014, at the end of a residency to make portraits of local people by an arts organization in the West Midlands. “I need people to photograph who’ve been bruised by life.”

It’s been said before, but it’s worth repeating, that Gilden’s work is the modern-day embodiment of Robert Capa’s mantra, “If you pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough”.

A member of Magnum Photos since 1998, he has said himself that, “the older I get, the closer I get”.

"I always rooted for the underdog... I need people to photograph who’ve been bruised by life."

-

Born in Brooklyn a year after the end of World War II, he has always been an acute observer of street life, and it’s here that he cut his teeth as a photographer, coming to international attention in the early 1990s following the publication of his first major book, Facing New York.

Employing his trademark in-your-face approach, “flash in one hand and jumping at people”, he has gone on to publish more than 20 further books, getting uncomfortably close to subjects as diverse as heavily-tattooed Bosozoku gangs in Japan, and the furrowed brows of dapper betting men gathered at racecourses across rural Ireland.

What remains a constant is his fascination with “characters”, and his identification with them. “A lot of people have been bruised by life,” he continues in the Multistory film. “You don’t have to be embarrassed. I mean, I made a lot of mistakes in my life.

“And that’s the trick in photography. You put who you are in the photograph. Most people haven’t lived a life. I almost died on drugs. My father was a gangster…. My mother was an alcoholic, committed suicide. I had a life. My guts are in those pictures. That’s why my pictures are really strong.”

Now those portraits, shot from 2013 to 2014 in West Bromwich, Dudley and Wolverhampton – the so-called ‘Black Country’, a reference to the region’s past as one of the birthplaces of the Industrial Revolution – have been put out as an 180-page book by Setanta.

The book’s design, bound using stainless steel screws and with a cover printed with silver on black paper, is a nod to the factory and warehouse settings of the places where Gilden photographed. (There’s also a special edition that comes with a silkscreen-printed stainless steel cover and a print.)

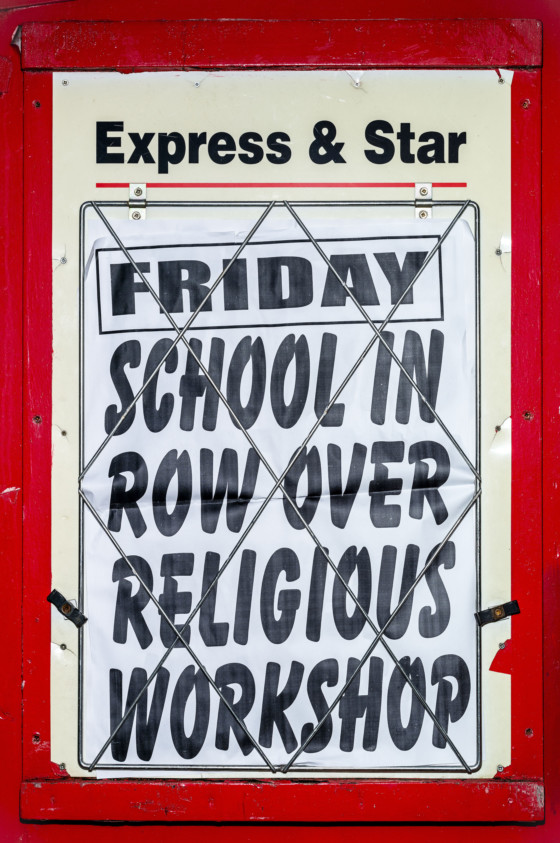

Inside, portraits, factory interiors, and the lurid headlines of the local press are presented in full bleed – the first time they have been seen since a selection was included in the Strange and Familiar exhibition curated by Martin Parr, first shown at The Barbican in 2016, then traveling to Manchester Art Gallery the following year.

Some were also included in Face, published by Dewi Lewis in 2016, which brought together work from many different locations, but which represented a change of course for Gilden, capturing people full face and tightly cropped, a new direction that is, in essence, more “collaborative”.

The West Midlands arts organization commissioned Gilden not long after he’d begun with this new approach, shooting in color, and working in even greater close-up than the street photographs he was famed for. In 2012, while working on a group project with Magnum in Miami, Postcards from America, he was given a Leica S2 to try out and, “Everything just fit: the color, Florida, flash and the subjects. It was a perfect match”. Transferring that to the grey and considerably less glamorous environs of the Black Country was not without risk. But, once again, the native New Yorker found a personal connection.

“I have travelled in about 50 or 60 countries, a lot of them in the Western world, they have all the same shops, the same stores, people look alike,” he explains in the Multistory video, filmed talking to a West Midlands audience. “Here, they maintain their identity… And they’re protective… And they’re very angry.”

“The thing is, I’m an angry person. And I know it. I channeled my anger. I made it a positive not a negative. I’m proud of myself when I look in the mirror. Because I could have turned out very differently, okay? I did a lot of crazy things, and I came a long way. I educated myself. And the problem with people like that is, they’re angry at everybody…. That makes lots of parts of The Midlands quite an interesting place. Because they’re so defensive about who they are and where they come from.”