Chris Killip’s Enduring Connection With the People he Photographed

In the second of her two-part profile of the life and work of Chris Killip, whose images are now represented by Magnum, Diane Smyth focuses on the late photographer’s intimate connection with his subjects.

“You know, Chris photographed my wedding,” says Sue Jaye Johnson, a journalist and filmmaker who was one of Chris Killip’s first students at Harvard University in 1991, and later on a friend. “I just asked him and he said yes. And then the whole experience was so surreal. He used a point-and-shoot, and he shot and shot and shot. And at the end of the day, he gave me a plastic bag filled with 20 rolls of film and said, ‘Here’s your gift.’

“I carried that film around like it was gold. Then, when I finally got it developed, I was like, ‘What? What was he thinking?!’” she laughs. “There was no iconic photo I could print and say, ‘This is our wedding.’ It was people talking, people caught biting into food.

“It really took me 20 years to understand what he was seeing. There’s no filter, there’s no posing, there’s none of that, ‘Let’s prepare for the moment to be photographed.’ There’s the minimum there could be between the photographer and what’s happening. It’s as raw and real as possible, and looking through the images, I feel like I’m there.”

It’s this same raw intimacy that runs through all of Killip’s work, and which helped make him one of the most revered photographers of his generation.

Two years after his death, his life’s work was celebrated with a retrospective book published by Thames & Hudson – available in the Magnum shop – accompanied by an exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery in London that runs until February 19, and then tours to Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Tyneside on April 1 (where it will run until September 3).

At his behest, his images are now represented by Magnum. Later this month. Magnum is staging its first show of this work, at the Magnum Gallery in Paris, titled, Chris Killip: An Anthology, which runs February 24 until May 6.

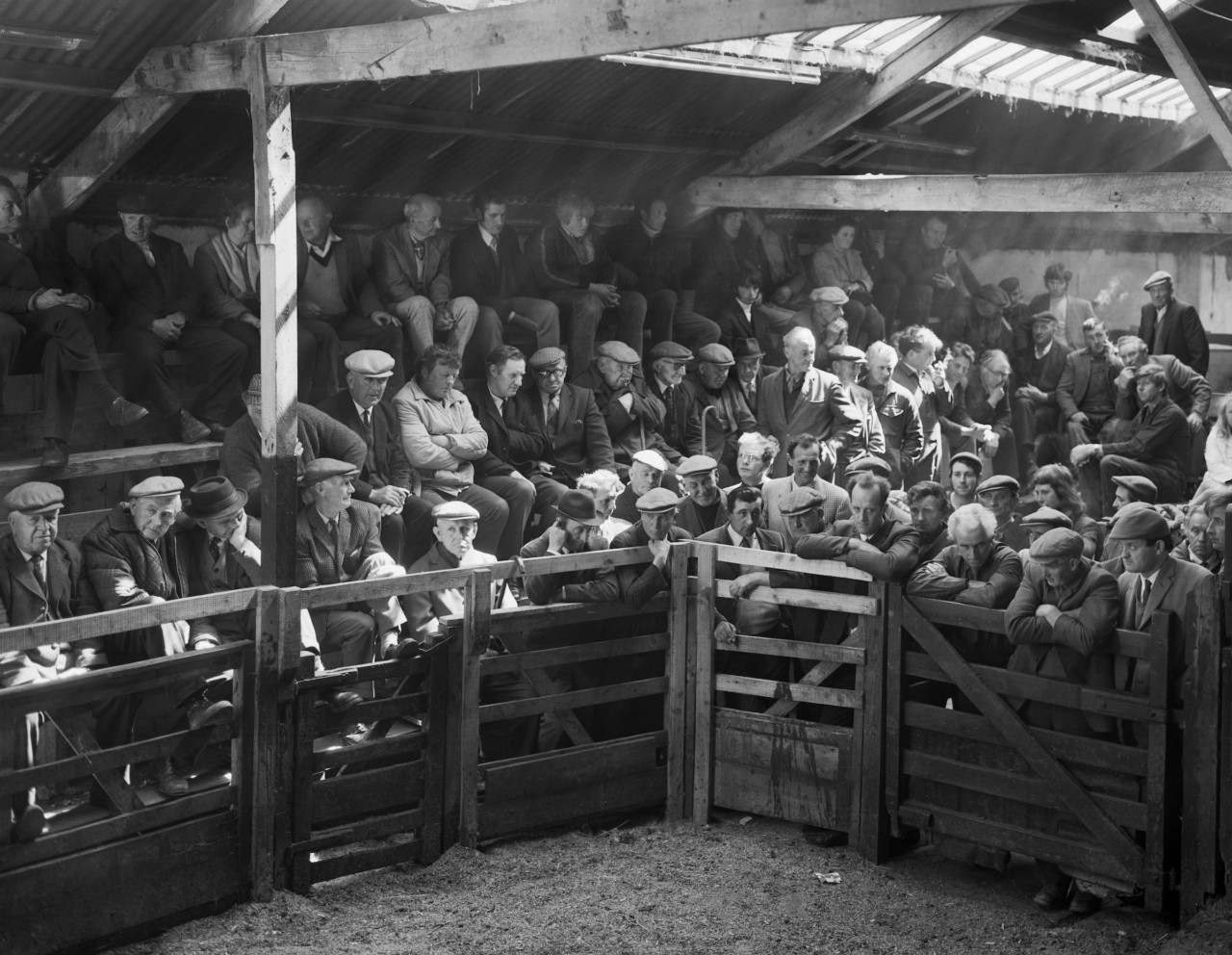

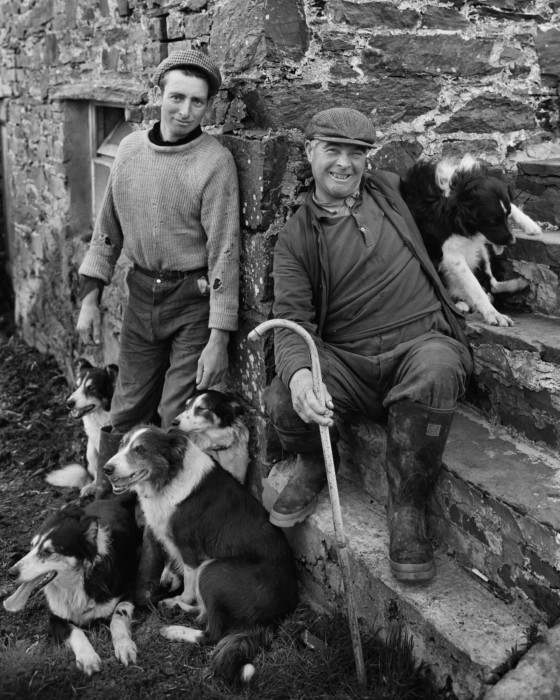

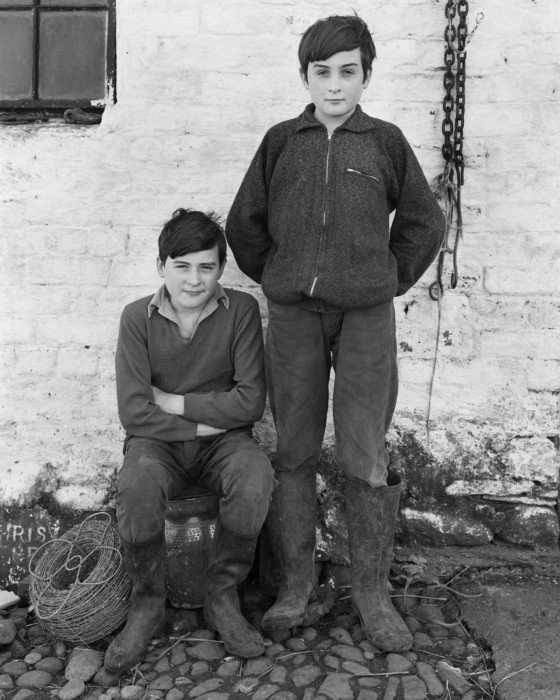

Killip’s first monograph was Isle of Man (published by Zwemmer in 1980, and republished in a much-expanded edition as Isle of Man Revisited by Steidl in 2005), a series of portraits that drew on his intimate knowledge of the island where he himself grew up, photographing its people, and its fast-vanishing traditional life.

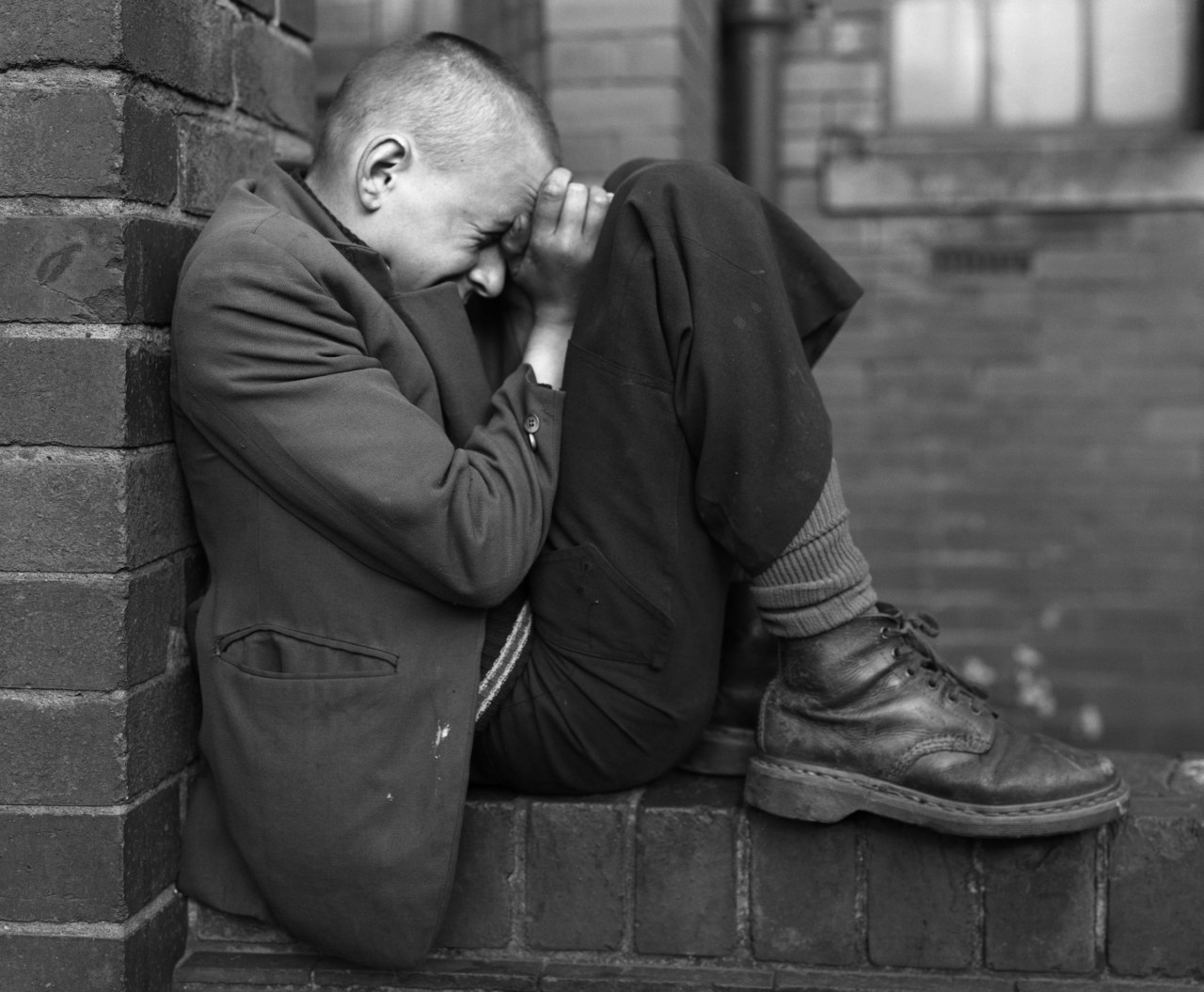

His next was In Flagrante (Secker & Warburg, 1988, reissued as In Flagrante Two by Steidl in 2016), his “subjective book about my time in England” during its “de-industrialisation”, which relied on his close relationships with those he photographed to allow him to photograph clandestine activities such as collecting sea coal.

“In order to photograph people, Chris embedded himself in communities,” says friend and fellow photographer, Sage Sohier, who taught with Killip at Harvard for more than a decade. “It’s clear when you look at his photographs that Chris was accepted and trusted.”

"His ability to get on with people shaped both his work and his life."

-

Killip arrived at Harvard University in 1991, joining the department of Visual and Environmental Studies as a visiting lecturer, becoming a tenured professor three years later and continuing through to his retirement in 2017. He had left school at 16 and never studied photography, but he wasn’t intimidated by Harvard’s reputation, nor overly impressed.

“Chris didn’t value hierarchy, or wealth, or that particular kind of intelligence,” explains Johnson. “The things he valued were just, ‘Are you meeting me in this moment? Are we sharing ourselves with each other?’”

Perhaps Killip acquired his sense of community because he grew up on a small island; perhaps it’s to do with growing up in a pub, run by his parents. Either way, his ability to get on with people shaped both his work and his life. Early on he worked as a beach photographer, a job drawing on the Isle of Man’s appeal as a tourist destination, but also requiring some charm.

Once he had got to Harvard, he made it his home for more than 20 years. But his affability didn’t come at the cost of his own integrity. In fact quite the opposite was true.

“When I graduated, Chris pulled my father aside and gave him a stark warning of how difficult it was to pursue a career in photography,” writes Magnum photographer and ex-student, Greg Halpern in the recent Thames & Hudson book, Chris Killip. “My father smiled and nodded and said he knew. ‘No, Mr Halpern, I’m not sure you understand,’ Chris reiterated, ‘You should know that what Greg is trying to do is going to be extremely hard.’

“At the time, my father was taken aback, but to this day we still talk about how much we appreciated Chris’ candor. As a teacher myself, I know how rare that kind of honesty is.”

Halpern stayed in touch with Killip for over 20 years and, like Johnson and Sohier, became a friend. That wasn’t so unusual. Killip’s long-term printer, Kent Rodzwicz at Tint Space, was another ex-student, and he stayed in touch with colleagues and those he had photographed back in England.

Killip co-founded and curated the Amber Collective’s Side Gallery in Newcastle for two years from 1977, and that’s how Martin Parr got to know him, “very impressed with the fact that all these photographers were getting grants and documenting that particular area of the North East.” The two remained friends for nearly half a century.

“He came here many times and spoke many times,” says Parr, referencing the foundation he set up in his own name, in Bristol. “He was one of my sounding boards. We would tell each other if we’d read a new book or seen new photography that was particularly exciting to know.

“For Rencontres d’Arles [which Parr curated in 2004] I did a show of 15 of his pictures done big. I thought he hadn’t been done big enough, because the quality is so great. It was a terrific revelation for people to see these 15 big prints at the exhibition.”

Parr describes In Flagrante as “probably the best postwar documentary photography book”, and it’s Killip’s relationship with the people he photographed that stands out.

“The rage in his work is one of the things I love about it,” says Halpern. “But, for me, it’s the way that rage mixes with a powerful sense of love and a deep sensitivity that makes the work so powerful.

“His images are impeccable… but the whole point is that you’re in a relationship [when you look at them], you’re in a community,” says Johnson. “It comes across with the repetition of the same people again and again, and it’s so obvious in his work that he’s not shooting from the hip.”

He was not trying to blend in to ‘disappear’ from view and shoot candid, she says. “He wasn’t becoming invisible, he was really engaging with the people he photographed and showing how important it can be to have a witness. It’s a way of honouring someone, to show up like that.”

This aspect of Killip’s work was important to him, and he often spoke of his images in terms of alternative histories – of recording those to whom history was done to, who had been disregarded and dispossessed. His work showed individuals against the backdrop of wider cultural and economic shifts: the Isle of Man’s move away from agriculture and fishing towards tax haven status, for example; the North-East’s change from heavy industry towards a still ill-defined future.

And this approach underscored what Killip did with his work after he’d shot it; his careful editing or his choices about how to show it.

Killip made sure In Flagrante was published by a literary imprint, Secker & Warburg, not a photography specialist, for example. In later years he revisited his earlier series and made new books, working with Steidl to publish Pirelli Work (2006), Seacoal (2011), Arbeit/Work (2012), and The Station (2020), as well as Isle of Man Revisited and In Flagrante Two.

"His book-sequencing was a huge influence on me, as well as his rigor with editing."

-

“He spent hours touching up my prints for me!” laughs Johnson. “I was just a student but there was this sense that this is what you do – that this is the work and you honour the experience and the subject by really stewarding the image.”

“His book-sequencing was a huge influence on me, as well as his rigor with editing – the moments he selected, in terms of body language, or the micro-expression on a face,” says Halpern. “The way he cared about the people he photographed was hard to miss. In that realm I think he set the bar, and I still find myself humbled by the way he cared for the people he photographed, even if the photographs weren’t always ‘nice’ or complimentary – two realities that are not necessarily at odds.

“He was very particular about who he allowed to exhibit or publish his work’ he was reluctant to hand it over to just anyone. Later in life, I noticed he became much more open to the idea of disseminating the work in various ways, including zines.”

"It was like the images were children; they were taken care of and in the right places."

-

The zines in question are a set of four tabloid-sized, unbound newspapers Killip co-published with graphic design studio Pony in 2018. They include The Station, made from a set of photographs shot at a co-operative punk venue in Gateshead in 1985, and Skinningrove, shot in the preceding four years in a small fishing village on the North Yorkshire coast.

The zine format appealed to Killip on a few of levels. Firstly, it made the work accessible and affordable. Secondly, zies were an integral part of punk culture. Thirdly and perhaps most importantly, he was able to give out free copies in Skinnigrove, getting opeople there involved in the distribution – people he still knew after so long.

“Chris was great at staying in touch with people,” says Sohier. “Some of his students would return years later and ask for his feedback on current projects, or just talk to him about their lives. He was very non-judgmental, and made people feel like he was on their side. He would get as excited about others’ success – books, shows, marriages – as about his own.

“He also returned to the communities he photographed to give prints and books to those he had photographed. It meant a lot to him to have that ongoing personal connection to people.”

Killip’s care over his images continued right up to and beyond his death in 2020. Having been diagnosed with cancer, he had time to put his affairs in order, and that included ensuring his work was safe.

He sent 20 images to the gallerist Augusta Edwards shortly before he died, for example, so that his photography could be exhibited alongside Graham Smith’s in 2022, the first time since their celebrated 1985 show, Another Country, at the Serpentine Gallery in London.

Tracy Marshall Grant used a picture edit he had already worked out when she co-edited the book, Chris Killip, published by Thames & Hudson last October. Killip also shepherded the retrospective of his work on show at The Photographers’ Gallery, London (co-curated by Marshall Grant, alongside her partner, Ken Grant, both long term friends of Killip).

“I got to see him in August 2020 and he had printed everything he wanted printed, he had the books going out, he had the show coming up, he knew where the estate would be held,” says Johnson, referring in part to the decision to have Magnum represent his archive. “It was like the images were children; they were taken care of and in the right places, being held in ways that will honor them and keep them available. It seemed to me such a form of love that at the end it was so important that everything was taken care of.”