Chris Steele-Perkins: Brixton 1973-1975

The British photographer created an unplanned portrait of everyday life in the multi-ethnic neighborhood that he made his home in the mid 70s

Chris Steele-Perkins was only two years old when his family moved from Burma to England in 1947. Growing up in Burnham-on-Sea, he recalls being the only biracial person in the seaside town, creating a profound sensitivity to the “other” in a racially-homogenous area of the country. “I’m not saying I had a terrible time but I was aware of being different and not being English, which at that time meant white Anglo-Saxon Protestant,” Steele-Perkins says.

After graduating from the University of Newcastle- upon-Tyne with a degree in Psychology in 1970, Steele-Perkins began working as a freelance photographer and quickly realized he would need to move to London to make the kinds of stories he wanted. Recognizing a kinship with outsiders, Steele-Perkins was drawn to document British subcultures and urban poverty at the start of his career. Recognizing the camera’s ability to discern and distill the universal humanity of his subjects, Steele-Perkins also understood photography could be used to expose the systems of power designed to oppress the most vulnerable.

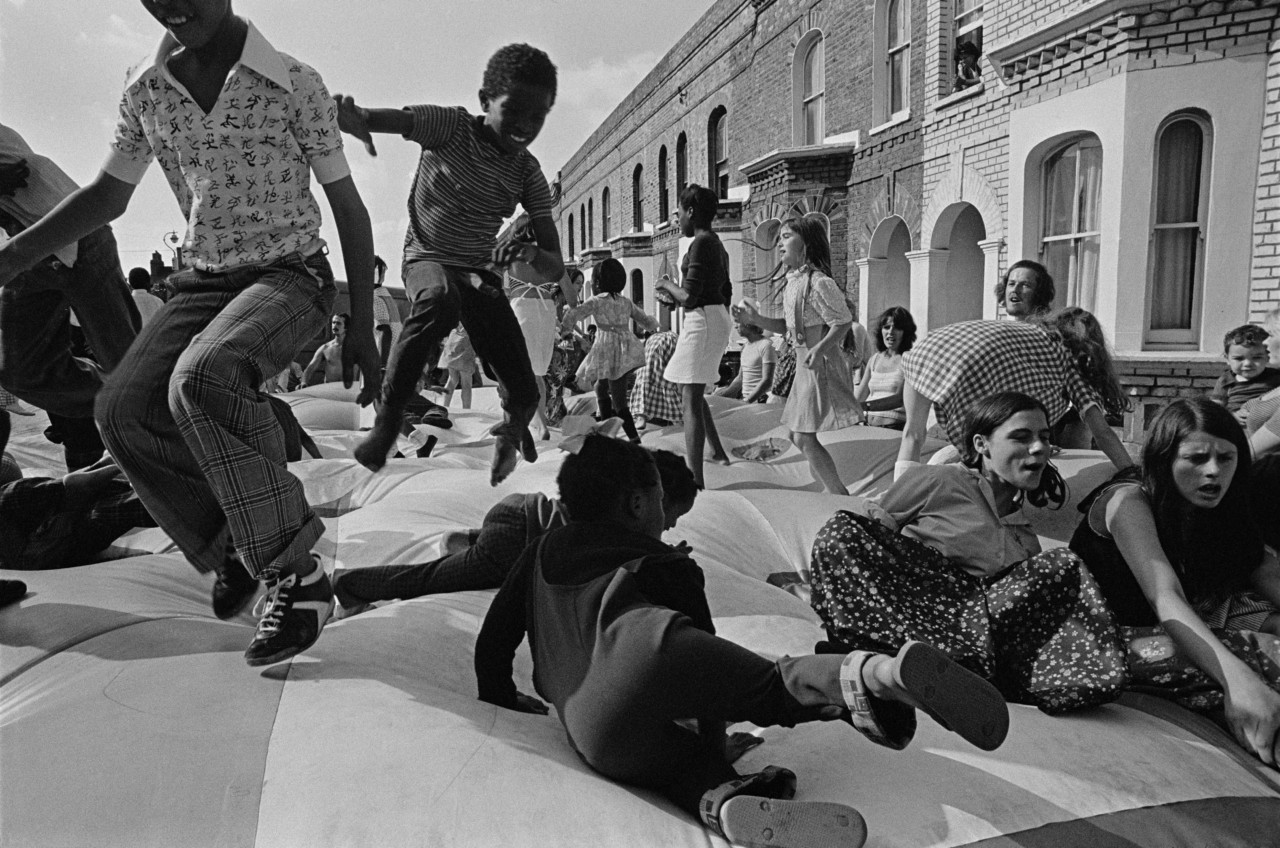

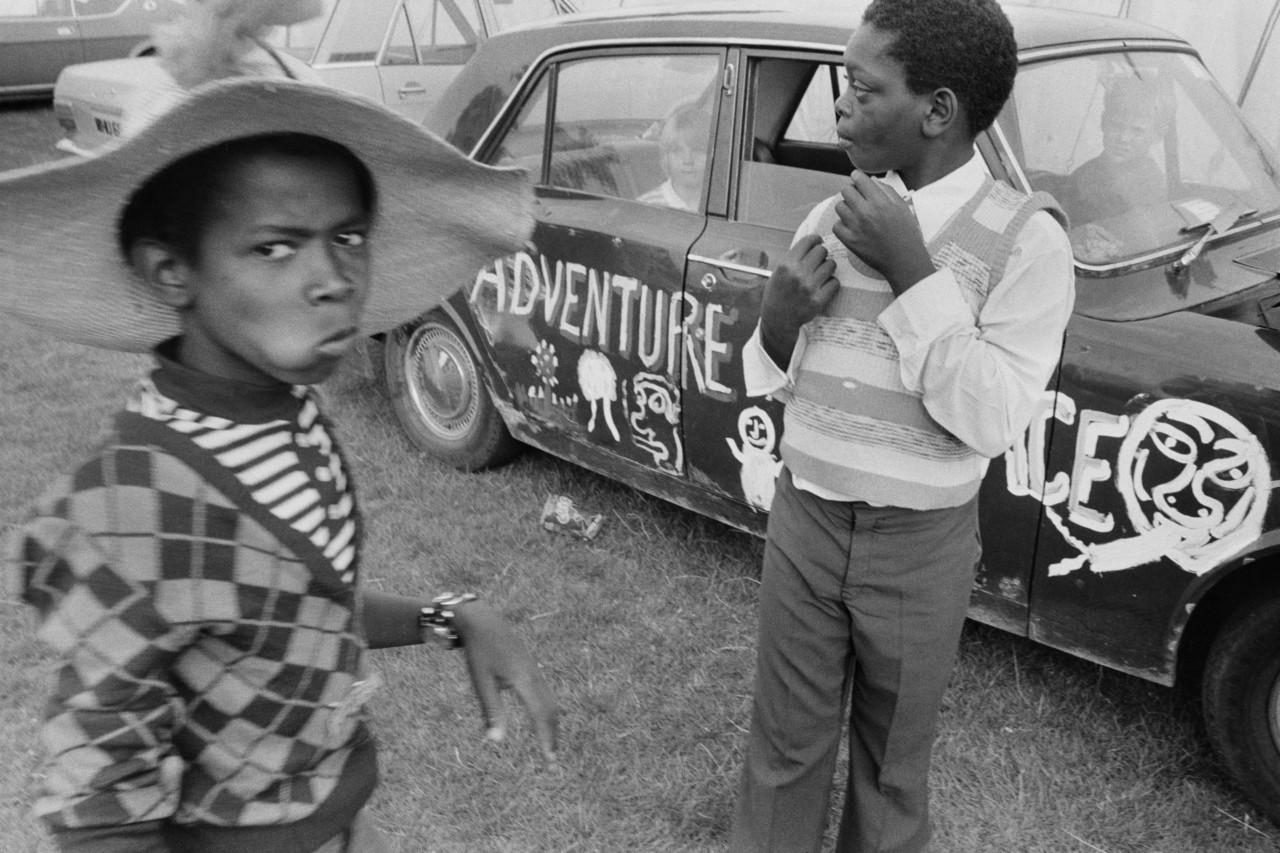

“Coming from rural Somerset, the kind of mixtures of people in Brixton was completely of a different order,” Steele-Perkins says. “I never set out to photograph the community there; I did so by accident. I told myself that Brixton was going to be home and home wasn’t where I did photography – I went out. But things creep up on you and you start doing this and that. Gradually I realized I had made a little community document.” Though he chose to move to Brixton for pragmatic reasons, it proved to be the perfect fit as the diverse community of Afro-Carribbean, Indian, Asian, Irish, and working class Britons appealed to the photographer’s newfound idea of home.

Steele-Perkins began organizing the photographs for the inaugural exhibition at Photofusion Photography Centre, a local Brixton gallery, which opened a new space this past May. A selection of his photographs were then collected in Chris Steele-Perkins — Brixton 1973-1975 (Café Royal Books).

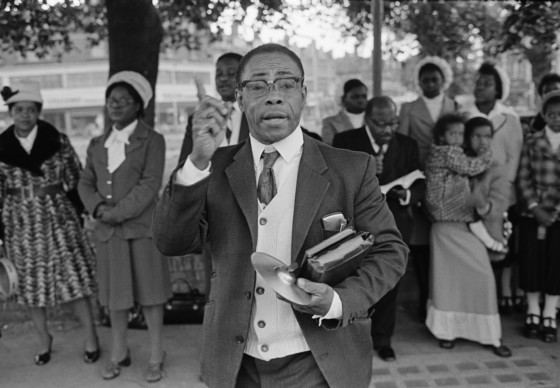

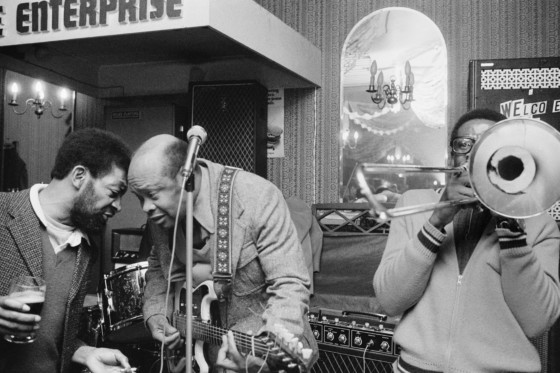

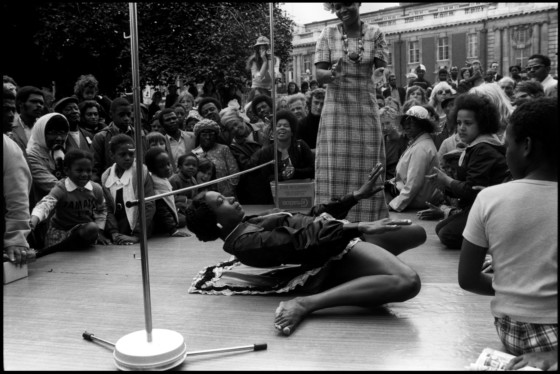

Music, dance, and community thread their way throughout Steele-Perkins’ work, whether it is hymns sung in church or live bands in local pubs. “The pubs were really melting pots,” Steele-Perkins says. “You had the young, the old, the black, the white, the women, the men — and Chubby Mullins and His All-Stars, who were just fantastic. [Mullins] worked for British Rail in the daytime and at night, the band would play weekends in Brixton.”

"Things creep up on you and you start doing this and that. Gradually I realized I had made a little community document."

- Chris Steele-Perkins

Unlike his celebrated Wolverhampton series documenting the black community of the West Midlands on the 10th anniversary of Enoch Powell’s infamous 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech — which stirred fears in the population towards immigration from the Commonwealth — Steele-Perkins had no political aim for his Brixton photographs. Yet his commitment to seeing people as they are has resulted in a powerful portrait of Brixton in the 1970s.

The reality of life for many Afro-Caribbeans in London was systemic racism as well as bigotry on an everyday level. From discriminatory housing, employment, and education policies, to police brutality; black Britons were also denied entry to churches, stores, restaurants, and pubs. Whilst no formalized policies enforced the segregation of black people from public life, such discrimination was commonly and openly practiced on an informal basis. The Windrush arrivals ended in 1972 when active measures were taken to restrict Afro-Caribbean immigration, barring entry to those who did not hold work permits or have parents or grandparents born in the UK.

By that time, conditions were growing increasingly bleak as widespread unemployment hit Afro-Caribbean communities particularly hard — whilst overall unemployment in Brixton was 13%, for minorities in the area it stood at 25.4%, according to the UK government’s Scarman Report of 1981. Tensions were exacerbated by police violence: Steele-Perkins arrived in Brixton at a pivotal time in the community’s history, in the years leading up to the 1981 Brixton Uprising. This was an event in which a reported 5,000 people took part in riots in the area; by this point, Margaret Thatcher’s anti-immigrant policies and cuts in public spending had been affecting urban working-class communities for several years.

During the 1970s, the far-right National Front party tried to heighten racial tensions and stoke the flames of discord. “The National Front was making it difficult for immigrants of color, whether it was Asian, African or West Indian,” Steele-Perkins says of the party whose demonstration in Lewisham he documented in 1977. “They were turning up and giving out their newspapers in Brixton. They did it in the East End around Brick Lane and they had a stronger presence there. I think the Black people in Brixton had a more robust response to the National Front and essentially kicked them out.”

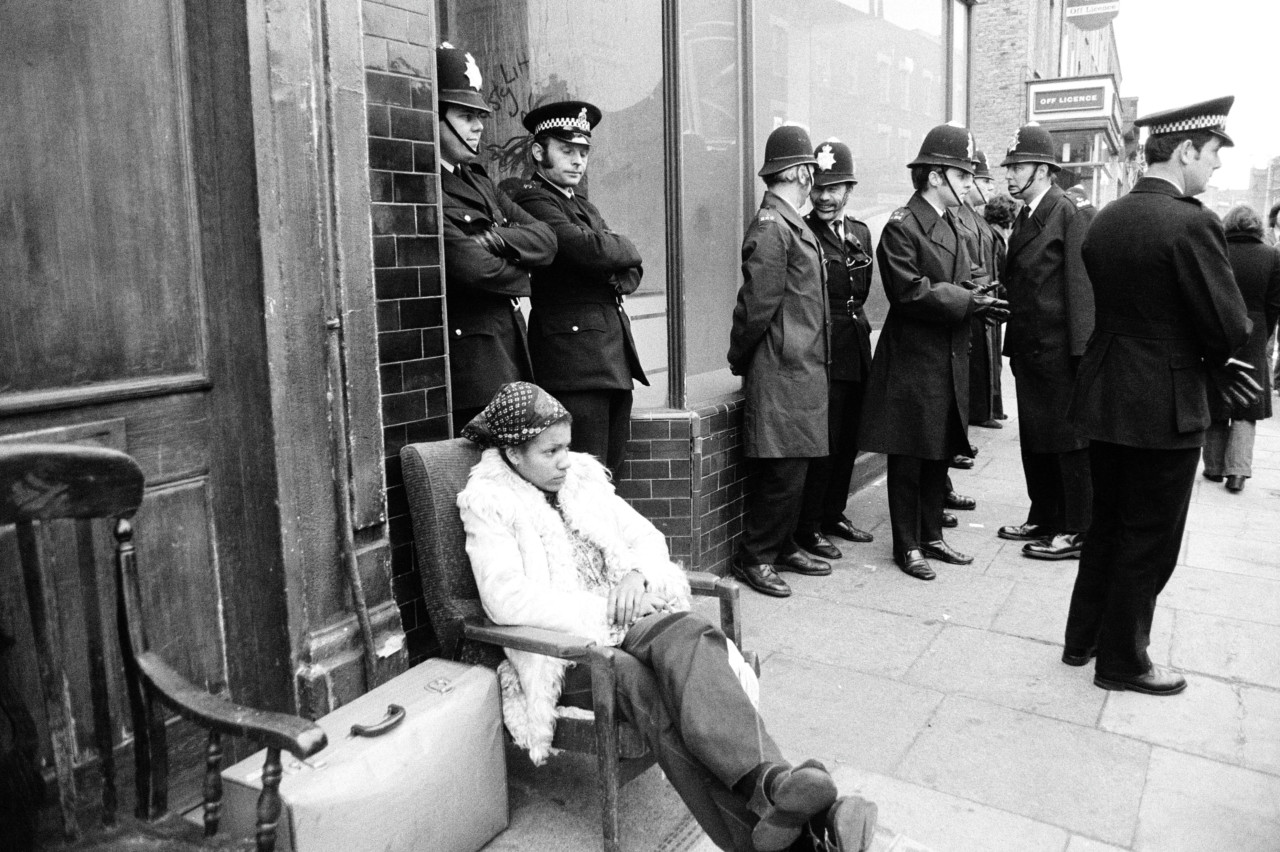

Brixton residents had less power over the police. “There was a time the police were going around in vans, pulling young black men off the street, giving them a kicking in the back of the van, and then dumping them out again. The police deny this and have always done so but it’s absolutely true.” Accounts of such directed brutality at the hands of the police remain anecdotal, but heavyhanded approaches to policing, supported by sus law — legislation that allowed police officers to stop and search ‘suspect’ individuals on suspicion of crime — were deemed disproportionately employed against black people (as also detailed in the Scarman Report).

These actions planted the seeds of distrust that sparked the 1981 uprising, which began when crowds believed Michael Bailey, a young Brixton resident, died as a result of police brutality. Though Steele-Perkins had left Brixton by then, his earlier photographs of police in the area reveal in their presence an exagerated show of force.

In one of his best-known photographs from this series, Steele-Perkins captures attendees at a reggae festival in Brockwell Park. “There was a sense that the police were going to turn up in numbers to break it up, which didn’t happen, but the tension was there,” Steele-Perkins says. “The predominant media coverage of migrant communities, black in particular, was as hotbeds of crime and violence,” says the photographer, though in reality much of this violence came from police, as those images of the Battle of Lewisham show. “But it’s not all violence; there are a lot of pictures of people having fun. That’s how I like to go about reportage in general, to try to look at all sides of the coin rather than just the dark side.”

Indeed, a single, sunny image of the Children of Jesus, a religious group of racially diverse hippie types, presciently speaks of an approach that Steele-Perkins has employed throughout his career. “I was using the group portrait format as far back as then and it’s something I have continued to use as a reportage technique,” Steele-Perkins says.

"That’s how I like to go about reportage in general, to try to look at all sides of the coin rather than just the dark side"

- Chris Steele-Perkins

It’s a theme he would explore at length in The New Londoners, a recent series of portraits of 165 families collectively hailing from 187 countries. Made in response to the refugee crisis and the issues of immigration that have stoked the flames of xenophobia throughout the West but particularly in conjunction with Brexit, the work celebrates all who call the UK home. “It is one of the key issues of our time. I feel very much that I am a part of this because I am an immigrant,” Steele-Perkins says.

“I was searching for a way to deal with immigration that wasn’t sensationalist. I wanted to photograph immigrant families in London who were from every country in the world living in their homes so that it was more rooted in the community and in this country. These were the people who were ignored because they weren’t rioting or causing trouble. When people talk about migrants being a drain on the community, I take that personally.”

As Steele-Perkins’ group photographs in both his Brixton and New Londoners work remind us, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It’s a philosophical approach that extends beyond the family into the community itself, where strangers become neighbors working for the betterment of all. It’s a mindset needed more than ever before.