Approximate Joy: How Christopher Anderson’s imagined future shaped a vision of the present

The photographer’s study of the melancholy faces of young émigrés pursuing their dreams in one of the world’s largest cities

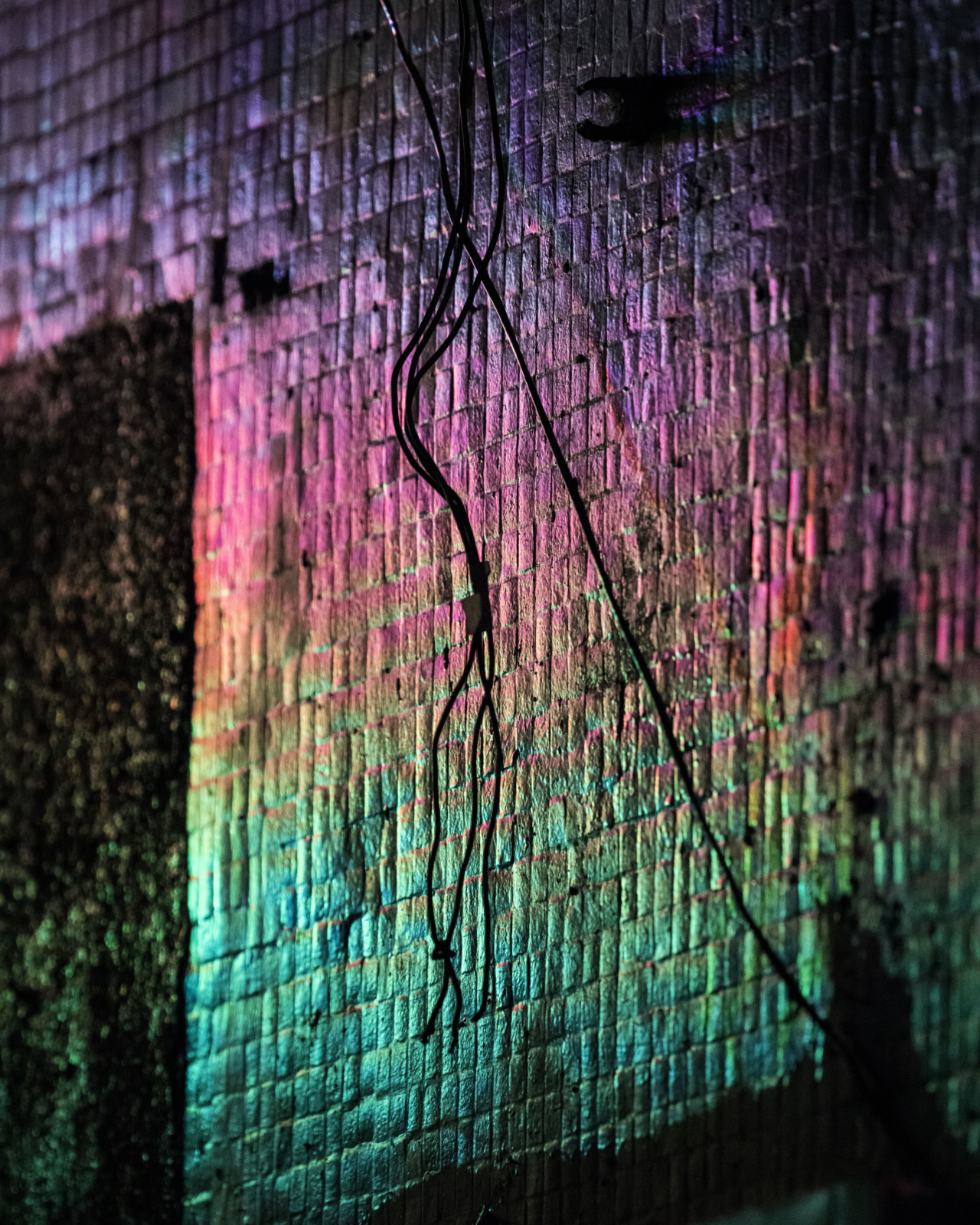

The below image is included in the new Magnum Editions Posters collection, featuring contemporary works from 23 Magnum photographers. These posters are now available, in limited editions of 100 unsigned, and 50 signed priced at $100 and $150 respectively. Each poster is individually numbered with a unique Magnum Editions label that is supplied separately. You can explore the whole collection here.

“Growing up in America in the 1970s and 80s, cinema presented us with three versions of what the future might look like,” says Magnum photographer Christopher Anderson. “There was the pristine future of Star Wars, there was the post-apocalyptic Mad Max version, and then there was this maybe more disconcerting dystopian future of Blade Runner. Arriving in Shenzhen, I remembered being told this is what the future would look like, and in fact, it does indeed look like they said it would.”

What is striking is the color palette that dominates Anderson’s new book, Approximate Joy, made with work he started in China’s fifth largest city, Shenzhen before going on to work in other cities China. “I think part of my mind was referencing, in a visual sense, the original Blade Runner, and the idea of how the city of the future could be anywhere: could be New York, could be Hong Kong, could be Shenzhen, could be London, where culture has melded together and the West has become East and the East has become West.”

"Who is this person? What do they dream about?"

- Christopher Anderson

To reinforce the sense of “anonymous megalopolis”, Anderson removes all context of place, focusing closely on the faces of the young populace, busying themselves about the city working towards their dreams. The presence of the city is not seen, but suggested by the illuminating glow of artificial light and tech screens.

“When I travel now, everything looks the same, there are patterns that emerge, patterns of predictability,” says Anderson. “When you go to an “exotic” place across the world, everything just looks the same: young people are wearing Chanel, listening to rap music, staring into iPhones. From a photographic perspective, to me, what people do becomes less and less interesting. Visually, cities look like airport duty free. This is why I wanted to eliminate the context and sense of place, and just look at people. The viewer is allowed the indiscreet pleasure of staring at another human and perhaps pondering questions like, ‘who is this person? What do they dream about?’”

The study is infused with the idea of a new, homogenized, global consumerism that plugs into the project’s title–Approximate Joy: “The idea of a consumerist society where human connection happens on a screen. The past is useless. It has been paved over and something new has been built on top of it that approximates happiness, but doesn’t quite replicate it. Approximate Joy: almost better than the real thing.”

This could be anywhere, but it’s also a vision of the future, with an emergent China at the forefront of tech and consumerism. Anderson seems to suggest that this is what the future will look like globally. The future is now. Shenzhen itself, a former fishing village-cum-metropolis, is one of the few places young Chinese are able to migrate to from the provinces. It is literally where the youth go to build their dream lives.

“If you look at the faces in the book, Shenzhen is a young city, young people are coming from all over to fulfil their dreams – it’s the tech city, the city of the future. They have all the modern things that we’re told we should want…the iPhones, the Chanel, the new Nikes…but there’s a certain melancholy in the faces. Perhaps I am just projecting the isolation that I personally experience when I am there. But I think it is a universal idea that hopes and dreams are infused with anxiety and frustration…maybe even fear.”

"The frustration of the youth coming to this place, seeking their dreams and ending up on the nightshift"

- Christopher Anderson

The only text that accompanies the photographs in the book is a poem by Xu Lizhi, who was a young contributor to Shenzhen’s tech industry, working in the infamous Foxconn factory. “His poetry dealt with the bleakness of existence at the coalface of the factory floor, and the frustration of the youth coming to this place, seeking their dreams and ending up on the nightshift,” explains Anderson, who is insistent that this isn’t a political book. “I didn’t set out to make a book about China, I think I made a book that comments on the idea of consumerist society and something that speaks to a more universal theme – the nature of happiness and consumerism. It just so happened that I photographed it in China.”