Daleside: Static Dreams

Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s new book with collaborator Cyprien Clément-Delmas portrays a primarily white, working-class South African neighborhood over five years and tells a story of race, class, and healing—on a personal and universal scale

Lindokuhle Sobekwa and his collaborator Cyprien Clément-Delmas have released a collaborative book project documenting the stories of the residents of Daleside, a post-industrial town on the outskirts of Johannesburg, South Africa, which they have made over five years.

Anne Nwakalor is Founding Editor of No! Wahala Magazine, a photography publication in print which champions authentic visual stories told by African creatives. Here she speaks to the pair about probing the divisions prevalent in the country, the unique aspects of working collaboratively on a photographic project, and how they got to know a small community over a period of years.

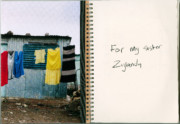

Daleside: Static Dreams, a book by South African Magnum photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa and French filmmaker and photographer, Cyprien Clément-Delmas, reflects on how life is for the residents of a working-class town on the sidelines of South Africa, which serves as a wider metaphor for the deeply rooted racial divide that persists within the country. This collaborative project, which was initially borne out of Sobekwa’s curiosity to return to the place where his mother worked as a domestic worker, resulted in the uncovering of a side of white South Africa that the world hardly sees at all.

Works from Daleside are on view at the Magnum Gallery in London until April 6 as part of Sobekwa’s first UK solo exhibition. Find out more here.

A small town located in South Africa’s Gauteng Province, Daleside was historically home to a population of white Afrikaner mineworkers and artisans who gained their wealth from the success of the adjacent, state-owned dolomite mine in the 1960s and ‘70s. Following apartheid, processes of privatization and globalization disrupted an economy that had been insulating white communities. Residents who could afford to pack up and leave, left, while those that could not afford to leave stayed behind in the increasingly desolate town.

Clement-Délmas, one of the first people who introduced Sobekwa to photography and who continues to serve as a companion and friend on his creative journey, joined him for this project, which resulted in a five-year period of going back and forth to Daleside, photographing the community and forming relationships with some of the families that were featured in their book.

Speaking to Sobekwa and Clément-Delmas about their work and experiences whilst shooting helped to add further depth and understanding of the significance of the project. The book is filled with images that somehow transcend time itself, their stillness both fascinating and disturbing, alluding to the limbo and somewhat static state that the residents of Daleside have found themselves in. The conversation with the two photographers revealed the understandings they gained while photographing the Daleside community over five years. The following interviews have been edited for brevity and clarity.

"I was curious to see what was inside."

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

Sobekwa: “I’ve always wanted to go to that place, I was curious to see what was inside. I realized that going back to Daleside was completely different from what I saw as a child and what I experienced there.”

Clément-Delmas: “For me, the project was also initiated by curiosity. Curiosity for those Europeans who left during the 17th and 18th century to settle in this place. I felt we were related but also very different. I felt similarities but also strangeness.”

For Sobekwa, Daleside was more than a spontaneous body of work, it was a place he had unresolved issues with, a place that took so much from him, leaving the photographer with enormous curiosities and unanswered questions.

Looking at Sobekwa’s images, one notices a gaze that many subjects of his images direct towards the lens. It is a glare that alludes to the underlying racial issues that remain in South Africa — the remnants of segregation. The sometimes fierce stares of some subjects create a distance between the photographer and the photographed. They uncover Sobekwa’s conflicting relationship with Daleside.

Sobekwa: “First of all, South Africa is a very divided country, it is divided by race and by class. The division is visible here. I really felt those hints of racism in Daleside, and obviously it did affect me: being seen in a negative way. I remember when we entered Daleside, many people thought I was either Cyprien’s assistant, a worker, or a criminal. I constantly had to prove them wrong and show them what I was there for, which in my case was my curiosity.

Daleside took a lot from me, my mother was always there helping their children. Our mothers came home tired and never gave us the same attention that we witnessed them giving to the white kids. The discrimination was there, and I felt it, and I tried to put it into photographs. I am not that good at expressing myself with words so I try to do so through images.”

Clément-Delmas: “I spoke with Lindokuhle about being insiders and outsiders. The fact that I am white meant that I was instantly seen as an insider and it was easier for them to relate to me — but in fact, I was the outsider coming from over 10,000 kilometers away. Lindo, who was coming from about 10 kilometers away, was actually the insider, but was not seen as such. It shows how people are segregated and demonstrates that there is still a lot of work to do.”

Clément-Delmas’ use of the warm glow caused by golden hour, creates an angelic — almost supernatural — feeling. His approach to photographing the community also gives the viewer a sense of the stillness in Daleside: the use of a medium-format camera contributes to this. The almost-statue-like state of his subjects not only translates to a sensation of time standing still, but also conveys another thematic concern of the project: one of religion and spirituality.

Clément-Delmas: “What really struck me in the beginning, were the little churches. There was one led by a repentant ex-white-supremacist, a priest who allowed everyone to come to his church. I really think that religion was a crucial part of the community. We gained access to a lot of families through the church because the priest introduced us to the whole community. When you enter the town, there is a small sign written saying, ‘Daleside is blessed with the blood of Jesus Christ’.”

The intimacy that is evident through the photographs in this book resulted from the level of access that Sobekwa and Clément-Delmas were able to get, a privilege which took a lot of time and effort to secure. After persevering through knocking on doors, facing numerous rejections, and not giving up over the five-year period, they were able to achieve the level of trust amongst the community that they did, and produce the special quality of work that they have.

Sobekwa: “The first year of photographing was not that great because people didn’t trust us taking photos of them. We responded to this by becoming consistent in our efforts to talk to and photograph them. Throughout this, Cyprien and I supported each other by feeding off one another’s energy. At the same time, we came up with different strategies to gain the trust of the community. We hung around a shopping center asking people if we could photograph them in their homes. We also visited a small church. There were moments I would go alone and it was quite difficult because I was no longer ‘with the white guy’. I was a black guy walking in a white neighborhood and had to carry the camera around my neck as my justification for being there. I also had my press card from when I first joined Magnum too. It was a good experience just being there: I learnt a lot and I hope people from Daleside learnt as well, from my presence.”

Cléement-Delmas: “It took a few years to gain the trust of those we photographed. I think the last three sessions were when we really felt like we were a part of the community. Daleside is quite small, so we were always seeing the same families every year. We would come with prints from the last session and those who were in them really loved it and would invite us to come and take more photos. But it takes time to get to know everybody and gain their trust. When we walked on the streets, people would stop us and say, ‘You took pictures of my uncle, come, come!’ We took pictures of the same people for four years, which is a process. Some of the people you see in the book— I have around 30 pictures of them that I have made through the years. It is really interesting doing a long-term project in a small community, because you really get to know them.”

The investment of time emanates here, narrating much deeper stories: of playfulness, of the spirit of the young adults who feature, stories of violence, pain, and loss. Sobekwa and Clément-Delmas share a few anecdotes of conflict that they witnessed first-hand.

Sobekwa: “When I returned to Daleside as a photographer, I realized that it was a community where I created a certain picture in my mind. There is a photograph that I took of two brothers fighting, which reminded me of things that also happen in my township —Thokoza, which has been affected by issues such as drugs and violence. I grew up in such an environment. That fight happened during a party for one of the brothers’ children and it was quite brutal. The two of them almost killed each other that day! But after the fight, one of the brothers left and then the other one came up to me and asked, ‘Did you get that shot?’”

Clément-Delmas: “We had a strong relationship with some families and really liked them. There was one family in particular that got separated during this project. Welfare took the kids away because the parents were on drugs and were accused of being violent. I remember Lindokuhle and I spoke a lot with the parents in regards to what they were going through. Both parents suffered abuse when they were younger, grew up on drugs, tried to build a family, then got back on drugs. Being in Daleside, we shared some degree of their emotions. We also witnessed violence, which is something that stays with you. You are a part of it, so you feel everything.”

This visual display of the disenfrachisement of a community as a result of poverty reflects the catastrophic consequences that the lack of investment and attention from the government has caused. The rare depiction of white people in an impoverished state has been considered a ‘taboo subject’: Clément-Delmas notes that the existence of white poverty has been a difficult pill to swallow for certain South Africans. Despite the difficulties and blockages faced due to race and class, there are sparks of hope at the end of the destructive cycle. This is seen through Clément-Delmas’ image of a white child and black child sitting together on their bicycles. This symbolic image suggests something of the possibility of unison irregardless of race and class, together in the mere appreciation of one’s humanity.

Clément-Delmas: “People recognized us in the street because we were a white and a black guy walking together and we were very proud of that. It is also a lesson to the community — communities in South Africa and other regions where whites and blacks don’t mix at all. We were the exception because we were friends.”

Sobekwa and Clément-Delmas’ five-year photo project transcended a simple photo book: it was a documentation of history, a photographic record of a white enclave where dreams were stuck in limbo, but also, a projection of what could be. Photography is so much more than a freezing of a moment in time: it is a tool to create social change by bringing to light issues that have been overlooked or ignored outright.

By bringing these wounds out into the open, a healing process can start to take place, a healing process for Sobekwa, a healing process for the families featured in the book, and a healing process that the viewers themselves have now been invited to be a part of.

Several copies of Daleside are now available to purchase from the Magnum Shop.