David Hurn: An Ode to Wales

How the lure and love of his home country shaped five decades of work, and resulted in a tribute gift to the institution that started it all

When David Hurn was five or six years of age, his mother took him to the National Museum of Wales. That experience of seeing the paintings and the sculptures had what the veteran Magnum photographer describes as “an extraordinary effect” on him. He particularly remembers his mother explaining how the museum came to have such artefacts through donation. “I loved the word donation,” he says, “I apparently used to use the word all the time in sentences, so one could say that my ambition from being about six has been to donate something to the museum.”

Almost eight decades later, that is precisely what Hurn has done. His personal collection of photographs, built through swapping and started long before photography was considered a valuable or collectable item, has been gifted by him to that very museum. “I started to collect photographs at a time when it was like collecting bus tickets,” explains Hurn, who has witnessed his hobby develop into a collection of not just incredible monetary value. Indeed, it features some of the world’s most well-known photographers, and is of huge cultural significance.

"I’m not a propagandist about it, I’m not trying to put forward a particular view of Wales"

- David Hurn

“Photos didn’t have a value other than you thought they were beautiful objects. So if you happened to collect bus tickets, you’d think they were wonderful things. I happened to collect photographs. In a way, what is bizarre is that those photographs, over a period of time, particularly when the galleries started, and people wanted to make money out of those photographs and turn them into art objects, became a very valuable collection…. it never entered my head to sell them, I just wanted to give them somewhere, and the obvious place to give them was my home city, Cardiff.”

Gifted to the museum under the condition that a permanent gallery to house it be built, the collection comprises original prints from the likes of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Josef Koudelka – photographers who have “influenced and enriched my life enormously” says Hurn.

“When I think of the people in this collection, boy oh boy have they allowed me to have a wonderful life being a photographer. It will be there for young people to aspire to, to have heroes to look at it and say ‘I want to be like that’.”

David Hurn, who was born in Redhill of Welsh decent, went to nursery school in Wales, but, for various reasons to do with his father being in the army, went to live in England from being around 6 years old. He didn’t come back to live in Wales until 1970, returning with the initial idea of staying for a year, but never leaving. He has lived there ever since. “I realized very quickly it was far less expensive than in London, and I could function in Wales, and work, and I bought a cottage there.”

However, the series of events that set in motion his move to Wales had begun much earlier. One of the major catalysts was Hurn’s coverage of the Aberfan disaster, a mining catastrophe that saw a coal tip slide down a hill on to a school, killing 116 children and 28 adults. Hurn, along with fellow Magnum photographer Ian Berry, was quickly on the scene photographing as local people worked through the night to dig out their children. It was a harrowing scene for any photojournalist, but for Hurn, it hit particularly close to home.

"I realized that I hadn’t really been back to Wales since I was about 6 years of age, so that’s what put the germ of the idea of going back to Wales in my head"

- David Hurn

“Of course it was particularly important to me because it was my country,” he says. “And the obscenity of photographing miners having to dig their children out of slurry hit home very much. I realized that I hadn’t really been back to Wales since I was about 6 years of age, so that’s what put the germ of the idea of going back to Wales in my head. I didn’t actually go back for another 4 years, but from the time of Aberfan, which was so powerfully ingrained in my mind, it was in my mind to go back to Wales.”

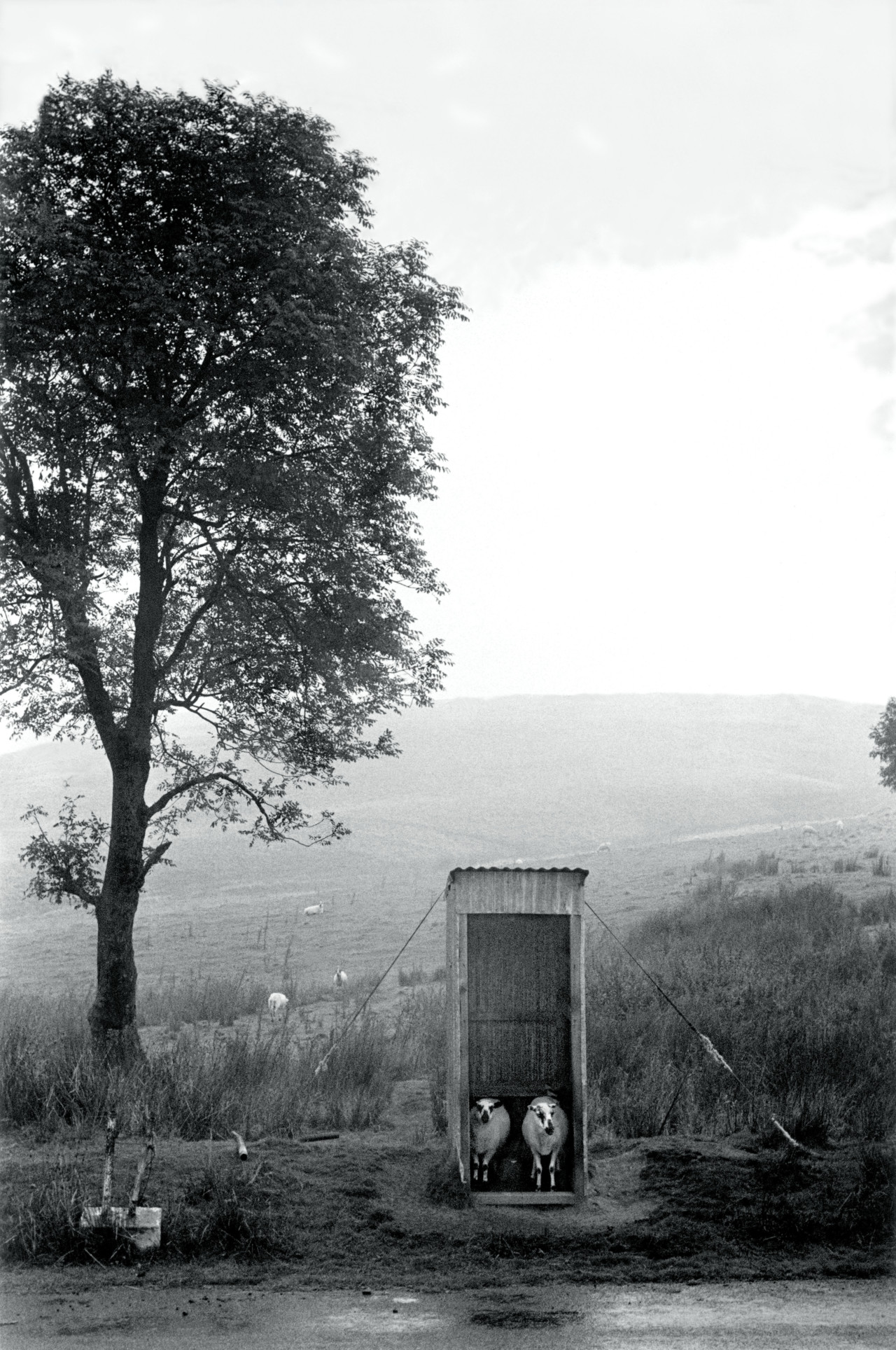

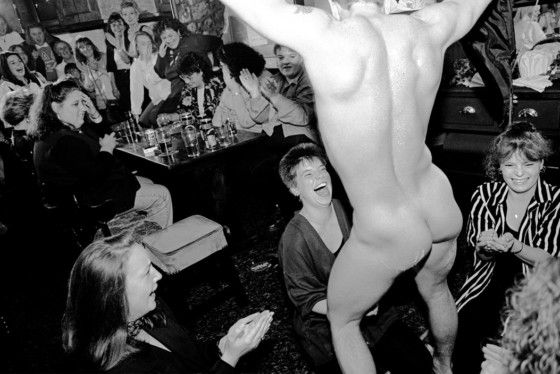

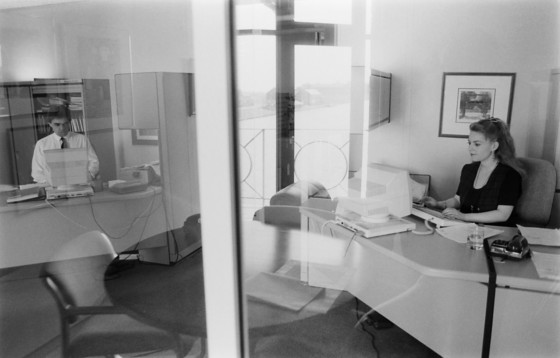

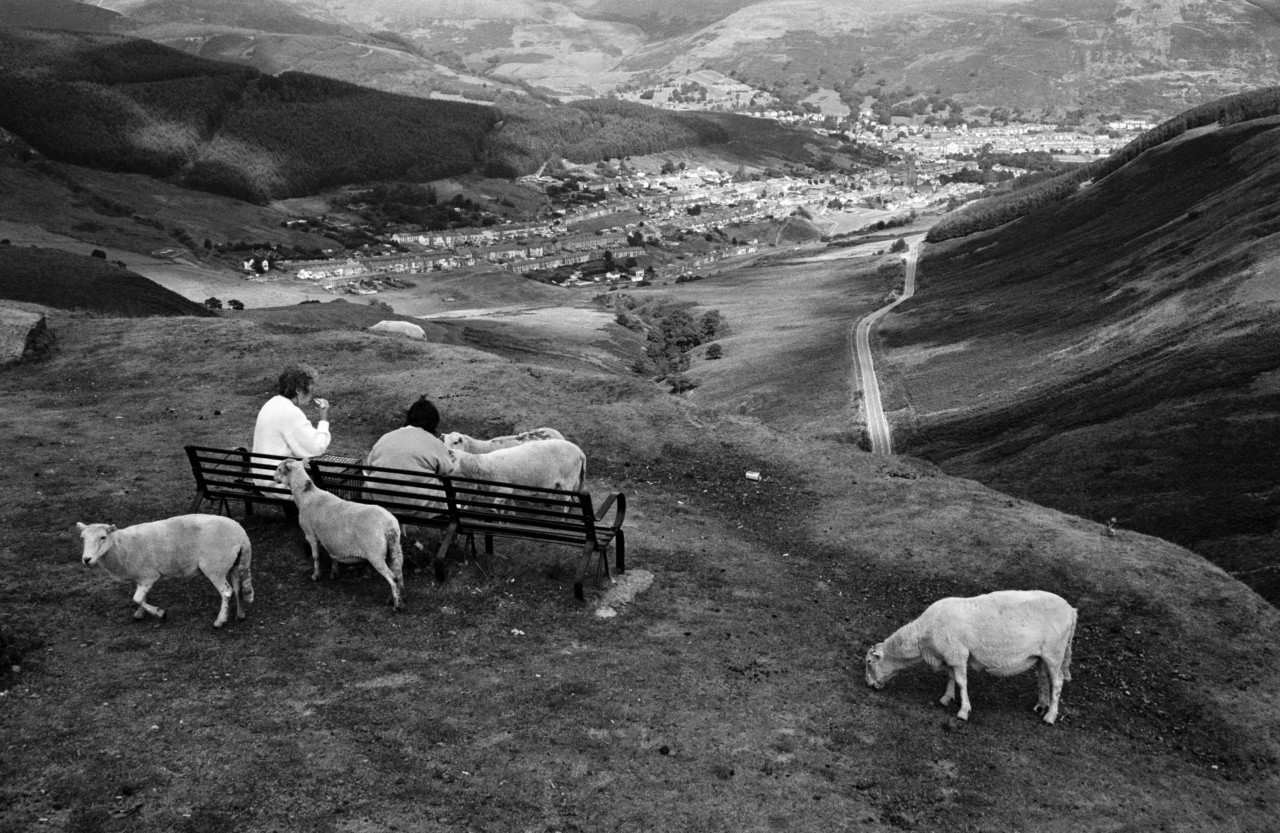

When Hurn did return back, he set about photographing the country. An old school documentary photographer, Hurn describes his approach as lacking an agenda – “I just go and involve myself in what’s happening and try to discover for myself what I think is significant about that particular place. I try to be open-minded about it. I’m not a propagandist about it, I’m not trying to put forward a particular view of Wales.”

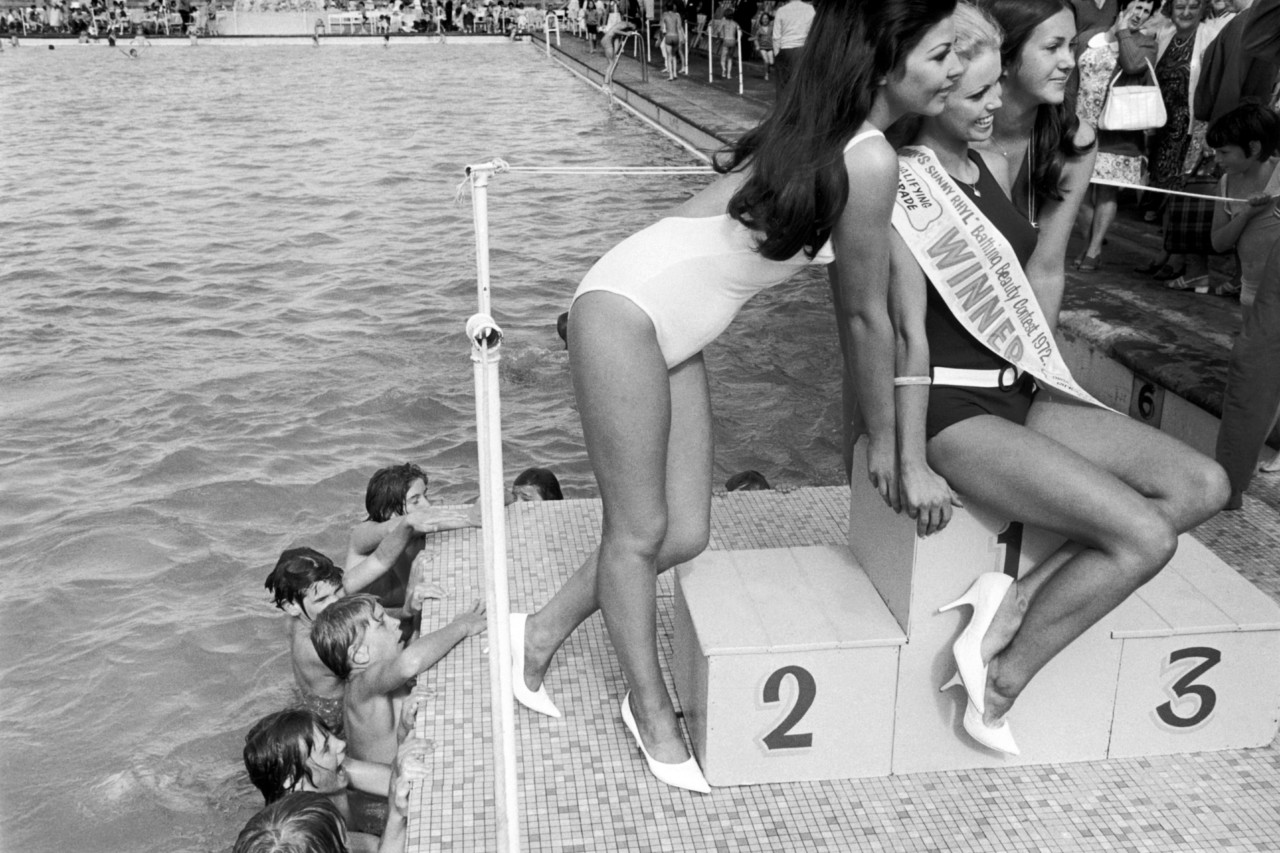

Through photographing the country, Hurn hoped he might be able to define something of Welsh identity. “The way I would do it was to wander around Wales and photograph the things that I thought were interesting or significant and maybe if I put those together like a jigsaw puzzle it would end up with something that would say ‘This is my Welsh culture’,” explains Hurn. “And of course that’s what I’ve been doing ever since. I’m still struggling to find what I mean.”

Over a period of six decades, Hurn charted the inevitable changes that take place anywhere over a 50-year period, beginning where some of the biggest changes, such as shifts in the industrial economy and landscape. This work has been brought together in a box set of six photo zines by Café Royal books. It comprises Wales, 1970s, Wales 1980s, Wales 1990s, Wales 2000s, Wales 2010s, and Wales Steel & Coal.