Dennis Stock’s Hawaii

As the Hawaiian islands mark 60 years since becoming a US state, we look back on Dennis Stock’s photos as we reflect on its rich landscape and cultural history

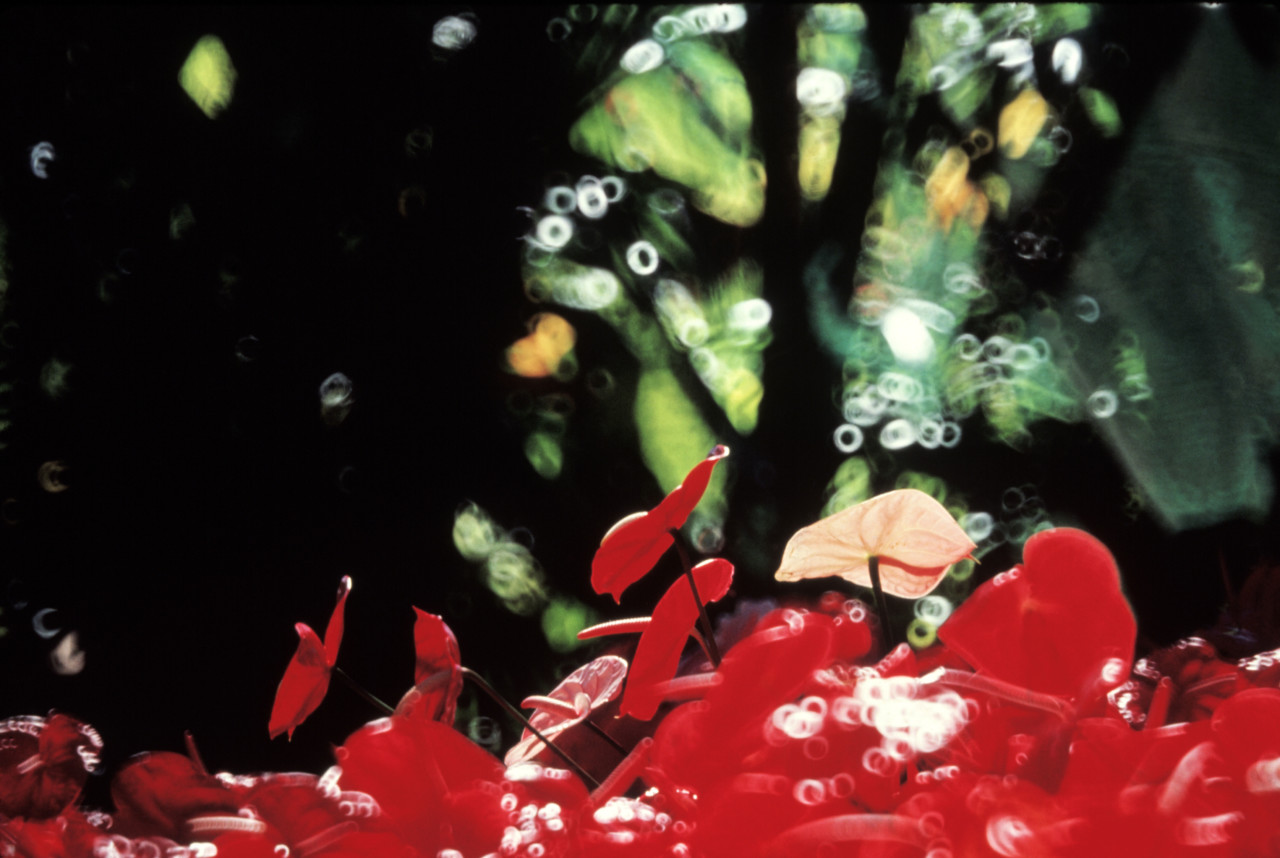

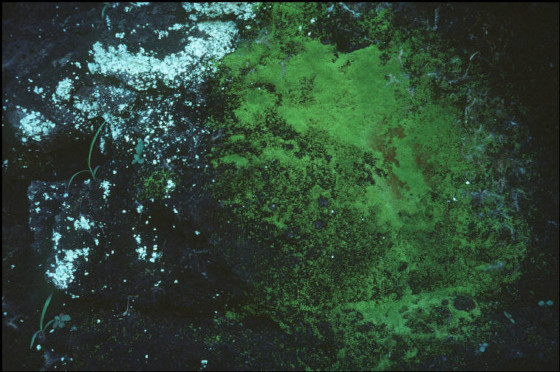

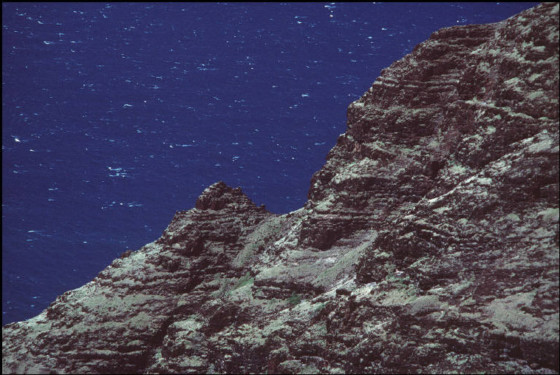

Since the first of the main Hawaiian Islands bubbled up from volcanic plumes and solidified above the sea’s surface some five million years ago, Hawaii has been one of Earth’s newest theaters hosting the dramas of life. Populated by storm-blown birds, current-riding terrestrial flora and ocean wildlife, as well as adventurous humans, everything—and everyone—has had to fight for their piece of this far-flung tropical Eden.

Hawaii’s remote exoticism has long drawn outsiders. Some 1,400 years after voyaging Polynesians became the first Hawaiians, missionaries arrived and began spreading new ideas while systematically subverting native culture, putting their own roots into the land. They discouraged Ōlelo Hawaiʻi, the native Hawaiian language, in favor of English, as well as traditional practices like hula (dance), oli (chant), and even pastimes like surfing.

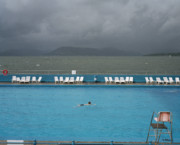

From an estimated population of some 300,000 at the time Captain Cook’s arrival until the industrial sugar era of the 1840s, war and disease had whittled down the native Hawaiian population to a quarter of its size. Then, an influx of sugar plantation workers that far outnumbered Hawaiians arrived from around the globe—China, the Philippines, Korea, Japan, Portugal—adding their own languages and traditions to the mix of local identity. By the time commercial air travel opened Hawaii to the visiting masses around the time the islands became the 50th U.S. state in 1959, hundreds of thousands of vacationing visitors washed onto its shores. In the short time between then and 1980, when Dennis Stock visited offering a glimpse of the Islands as they were, the number of wide-eyed annual visitors boomed to nearly four million.

A disconnect between the sanitized vacation-land concept of Hawaii sold to tourists—tiki-themed umbrella drinks, and hotels blaring California surf music—and the reality of the Hawaiian experience, grew as the volume of outsiders dwarfed native Hawaiian populations. In this, Hawaii experienced a Catch 22: As waves of tourists brought jobs and industry to the islands, it came at the expense of the natural beauty and traditional culture that visitors sought. Luxury hotels paved paradise and plants that were imported to diversify landscaping outcompeted native flora–many plants associated with Hawaii, aren’t actually Hawaiian at all.

More people put a strain on the island’s infrastructure; expansion not only encroached on the remaining wild landscapes, but also on the physical remnants of native Hawaiian history. An inflated tourism economy made it harder for native Hawaiians (and other lower income minorities) to live in their homeland. And, with a native population that had all but erased their historical culture, new exotic traditions replaced the old. Even today, the dance that most outsiders think of as hula and associate with Hawaii—with grass skirts and gyrating hips—is actually from Tahiti. Real Hawaiian hula didn’t experience a true revival until the 1960s.

When visiting writer Jack London saw a small group of Hawaii residents surfing in the waters off Oahu in 1905, he helped to spread word of the dying sport with the publication of his article “The Sport of Kings” in The Atlantic. The sport grew—in large part because of local ambassador/advocates like Duke Kahanamoku—and its said that when London returned to Waikiki ten years later, the local surfing club’s ranks had swelled to 1,500. Morphed and changed by California surfers, modern surfing—with its short boards and big wave jet-ski entries—is a highly evolved version of the ancient pastime.

It wasn’t until the early 1980s, around the time that Stock visited, that discussion of reintroducing Ōlelo Hawaiʻi in public schools began. At that time, the University of Hawaii developed a four-year language degree program; it was the first time that Hawaiian was the foundation of any form of government-funded education since 1895.

Cultures, including Hawaii’s, are rarely stagnant. In the last few decades, a new wave of “authentic” and “experiential” travel has prioritized finding “the real Hawaii.” This has translated to hotels staffing native Hawaiian cultural ambassadors, an increased interest in hula and Hawaiian language by residents and outsiders (Hawaiian was added as an official language to Google translate in 2016), and a broader awareness of the Hawaiian experience. Ever dynamic and evolving, Hawaiian culture is not stuck in its past, but instead looks to the past to inform the future. Perhaps going forward, the renewed interest in Hawaiian culture—particularly in tenant of aloha—will continue to shape and inform the construct that is Hawaii.

Meghan Miner Murray is a Hawaii-based science and travel writer.

Explore Holidaying culture through the lenses of Magnum photographers, here.