Ernest Cole’s Rediscovered Archive

With the arrival of thousands of his rediscovered negatives in the Magnum archive, we look at Ernest Cole's groundbreaking book on South Africa under apartheid, the mysteries of his life and the impact of his work

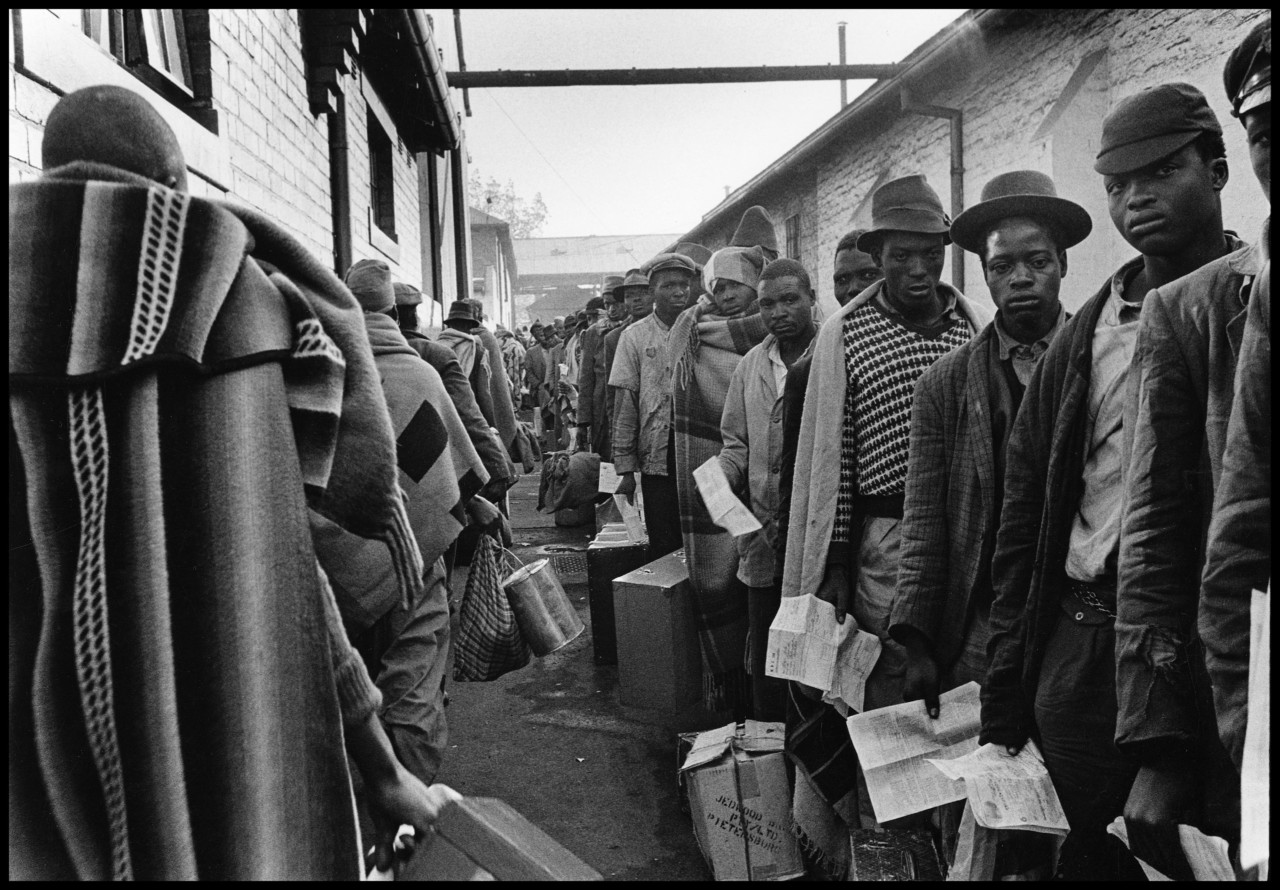

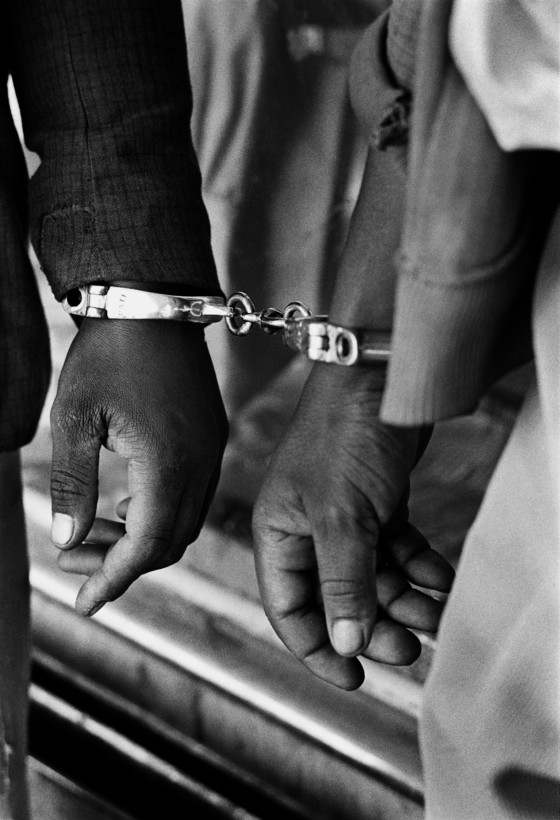

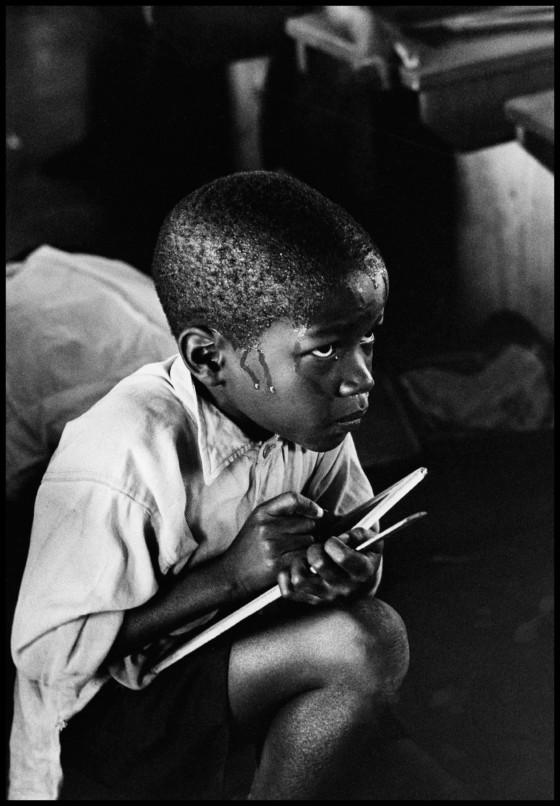

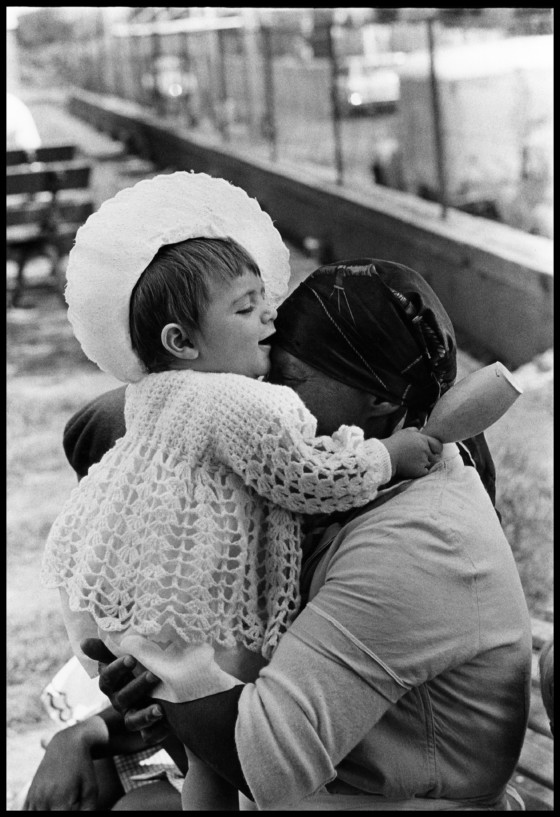

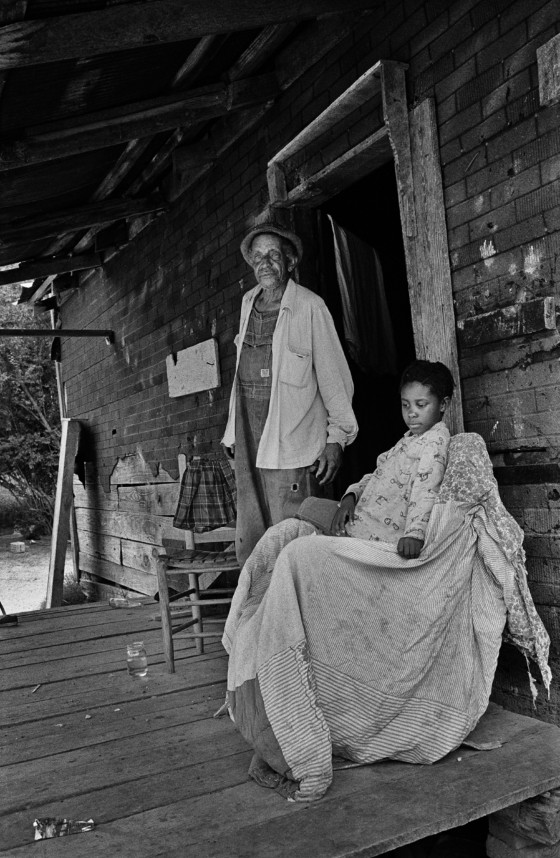

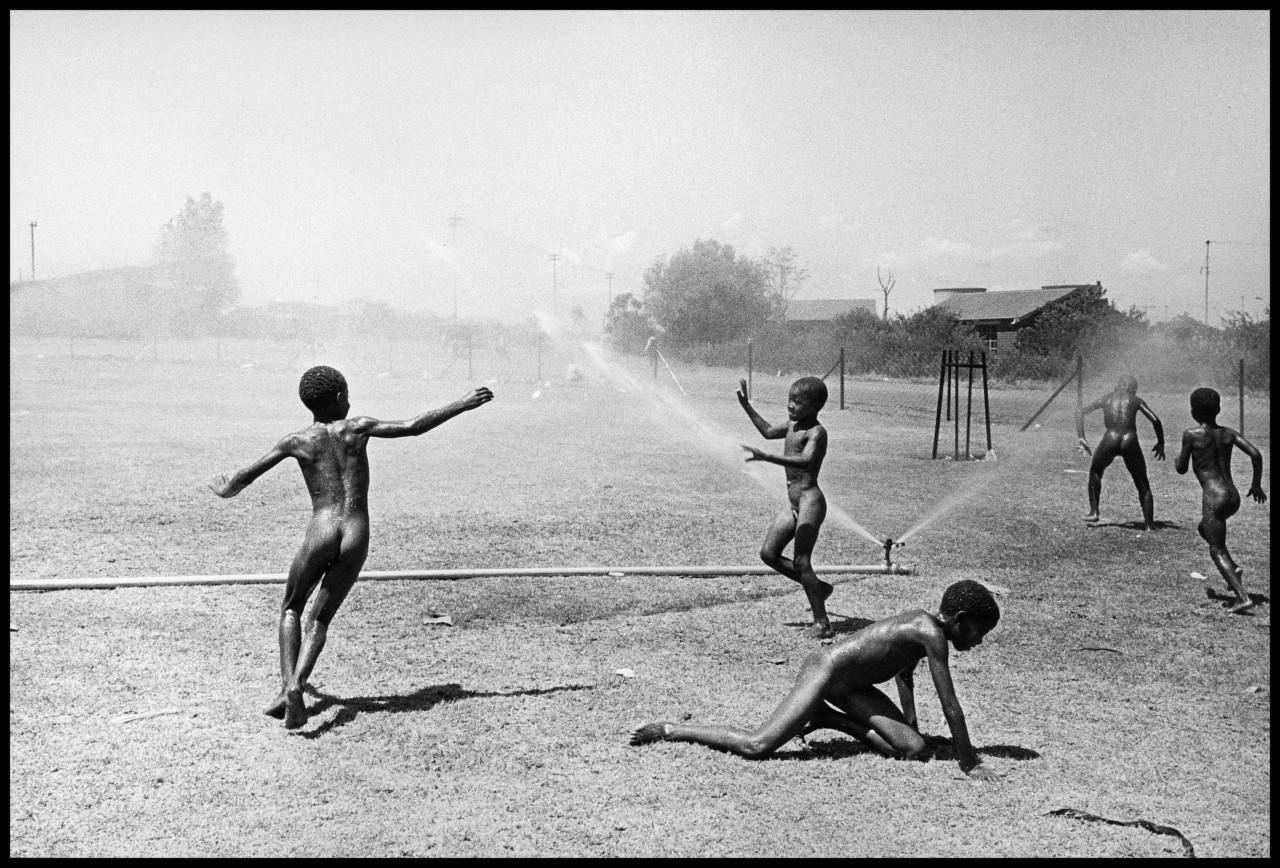

Ernest Cole was born in a township in South Africa’s Transvaal in 1940. His groundbreaking book, House of Bondage (recently republished by Aperture, and available in the Magnum shop), brought the daily realities, humiliations, and horrors of apartheid to the outside world for the first time, announcing Cole as potentially one of the great documentary photographers of his time. Unfortunately, he was to die in New York in 1990, destitute, having not worked in photography since the early 70s.

It was readily assumed that the vast majority of Cole’s negatives had been lost – it was acknowledged that some never left South Africa when he did, but there was also no trace of his subsequent work in the USA or Europe. Then, out of the blue, Cole’s nephew Leslie Matlaisane, was contacted in South Africa by a Swedish bank asking him if he would like to retrieve around 60,000 negatives from three safety deposit boxes. There was no information on who had placed the negatives there or paid for their storage, but the bank was now requesting they be removed. Matlaisane obliged in 2017, before bringing the work to Magnum in 2018. (There is a side-story concerning how the negatives ended up in a Swedish bank, but comment on that can’t be made until the investigation is complete.)

Within these 60,000 negatives is unseen work from South Africa that predates Cole’s exile, as well as work made in the USA until his retirement from photography. From these negatives and Ernest’s own notes we hope to solve some of the mysteries surrounding his life and his alienation from photography, and to gain a better appreciation of the incredible power of his work.

Here, Hamish Crooks, Magnum’s former Global Licensing Director, discusses what we know of Cole’s life and the importance of his work’s inclusion in the Magnum archive.

My first recollection of Ernest Cole’s photographs was in the late 1970s, coinciding with the growing global resistance to the apartheid regime in South Africa and my interest in the African National Congress. My father had a collection of photography books and I came across one by black South African photographer Peter Magubane. His series of news-focused pictures opened my eyes to the brutal regime, stoking my youthful anger. But my father pushed another book in front of me, one called House of Bondage, saying, “If you think that book was powerful, then try this one.”

While Magubane’s book reads like a series of events challenging South African inequality, House of Bondage had greater depth and read like one man’s testimony about life within the crazy world of apartheid. This was different to other journalists and photographers in that 99% of their work concentrates on the “other” – meaning the people and lifestyle being depicted is not the journalist or photographer’s own. House of Bondage is Cole’s life – he didn’t jet in and cover it, he lived it.

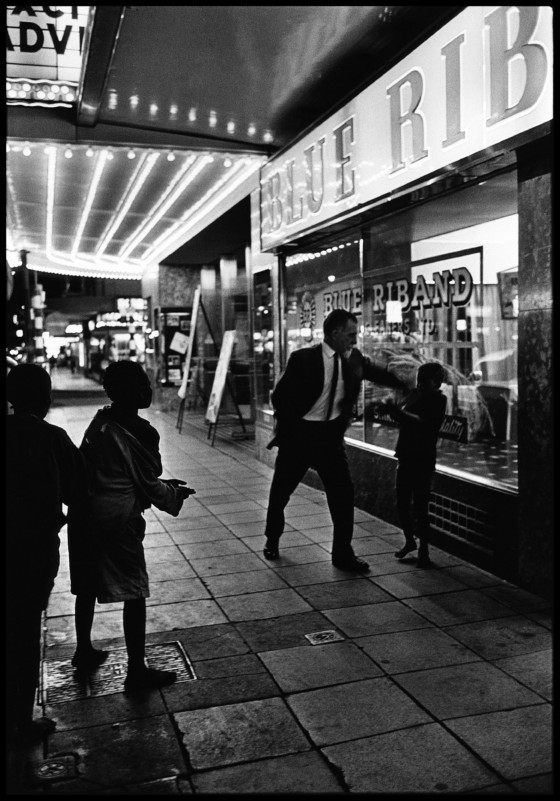

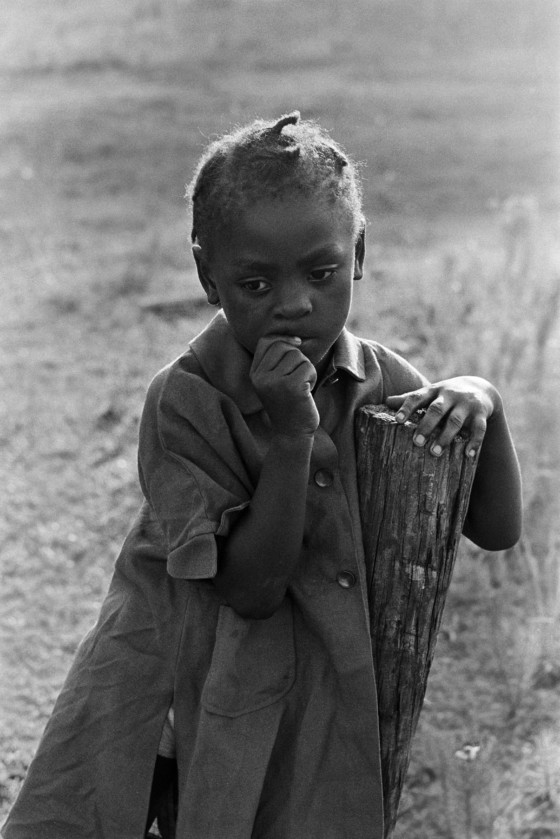

The images that struck me most were a series of pictures of a black child, of no more than eight years old, begging from a white man in a town center. As the series progresses, the man thinks nothing of refusing the child money, nor slapping him hard across the face in the same casual manner as one may flick a fly from food. I wanted to hunt that man down and, in the words of Marcellus Wallace in Pulp Fiction, “get all medieval on his ass”.

Cole’s photography career really started at DRUM Magazine – a seminal South African publication aimed at the black majority and focusing, when possible, on apartheid issues. DRUM’s staff were continually arrested for transgressing various apartheid or censorship laws. Cole was the first black freelance photographer in South Africa in a time when apartheid laws meant black people could only be employed as “labor”.

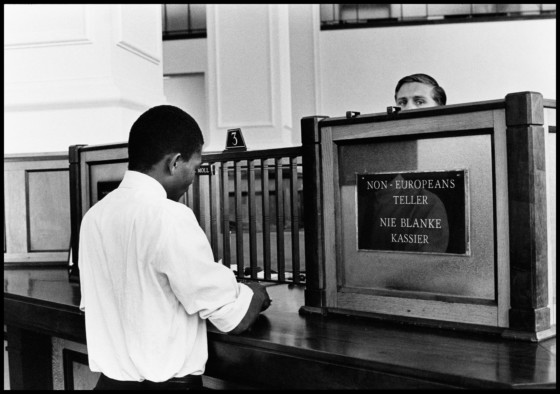

The Population Registration Act of 1950 divided all South African citizens into one of four groups: black, white, colored or Indian. These notional classifications dictated your life chances under apartheid, so for Cole to gain access to the stories that highlight the horrors of apartheid, he had to become colored, which he managed through outsmarting the authorities. He could now go into areas black people couldn’t. The stark brutality of the apartheid regime was laid bare in this racial classification process. Black people would lighten their skin to become officially colored or straighten their hair, as one test featured a pencil being placed in your hair – if it fell out, you were colored as your hair was less “afro”.

"Apartheid effectively outlawed being black, or colored, and educated. "

-

Cole used his time at DRUM, and the access it afforded him, to dive deeper into the stories he was assigned. He left DRUM in 1960, and freelanced for South African newspapers and the Associated Press.

What was interesting about Cole, or Kole to give him his born surname (his family adopted the more Anglicised version), is that he was always thinking of making a book. While he was doing smaller projects, or assignments, he considered how they fitted into a wider body of work. Magnum photographers such as Gilles Peress, Abbas and many others work in the same way – the photo book is the only way to truly get your message across, more effectively than one would in a page-limited story run in a magazine.

In a type-written biography, reproduced in the book Ernest Cole Photographer, Cole talks about The Europeans by Henri Cartier-Bresson – this is the book he most wanted his book to replicate. That’s interesting because Cartier-Bresson is very much about form over the content, whereas Cole is more about content over form. That’s not to say there isn’t beautiful form in his pictures – like most Magnum photographers he made beautiful photos – but the subject was key to him.

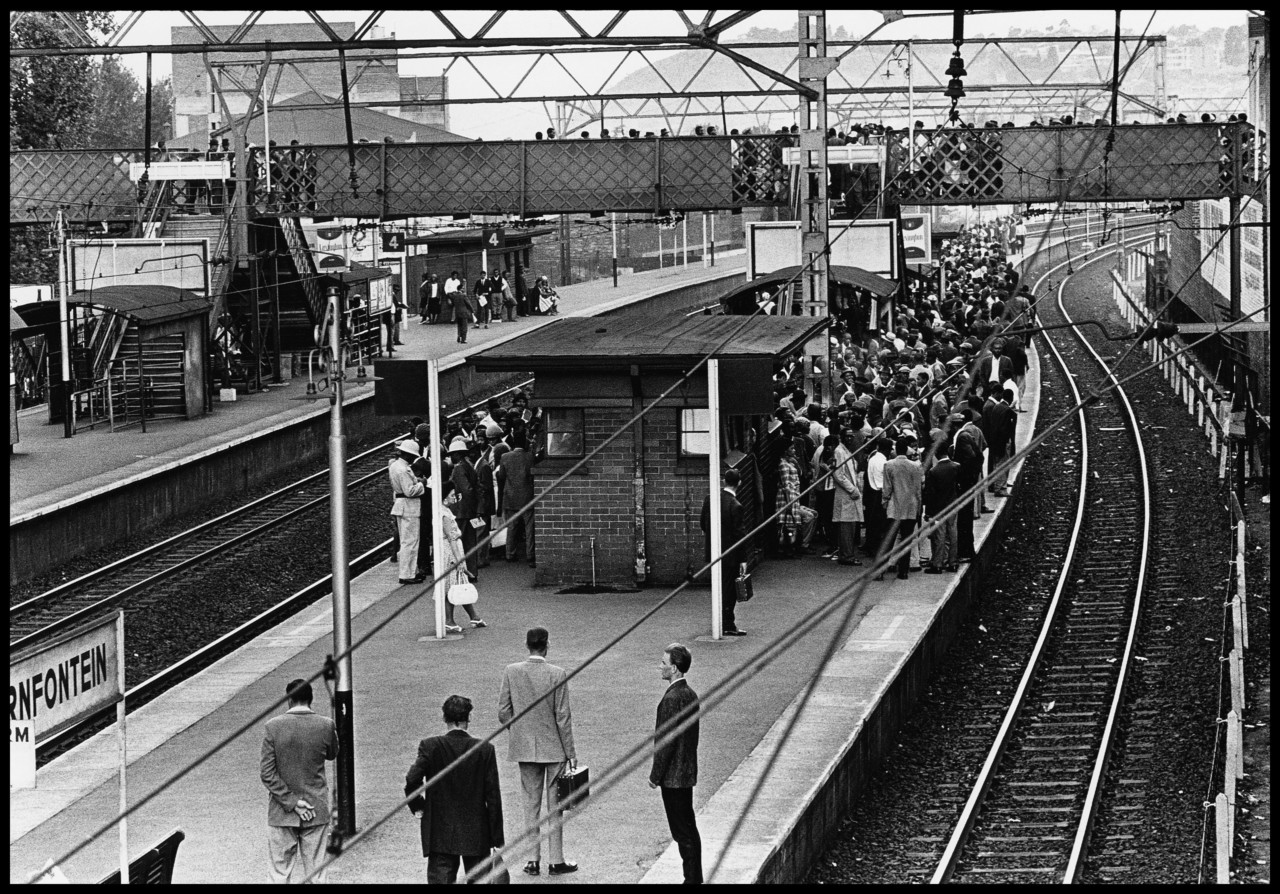

Cole existed, it seems, in this very middle-class, black South African world of the 1950s, a sort of intelligentsia based around a suburb of Johannesburg called Sophiatown. Similar to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, Sophiatown in the 1950s was the thriving cultural and intellectual center for black people – a one-time only creative collision of rural people arriving in the city. Unsurprisingly, Sophiatown was crushed by the coming of apartheid as racial segregation policies made existing injustices into law.

Apartheid effectively outlawed being black, or colored, and educated. It meant you could be evicted from your home and shipped around the country to “Homelands” you had probably never even visited. Cole’s family home was destroyed. They went from owning a house to having to pay rent, which fundamentally changed their circumstances, and made them poor – suddenly they were starving. He was part of a whole group of journalists, writers, musicians who experienced this. Nelson Mandela was of that generation too, one of many educated black people who suddenly had their lives turned upside-down. Many went into exile, others sank into the slough of despondency.

"It is a prowling and growling indictment from beginning to end"

-

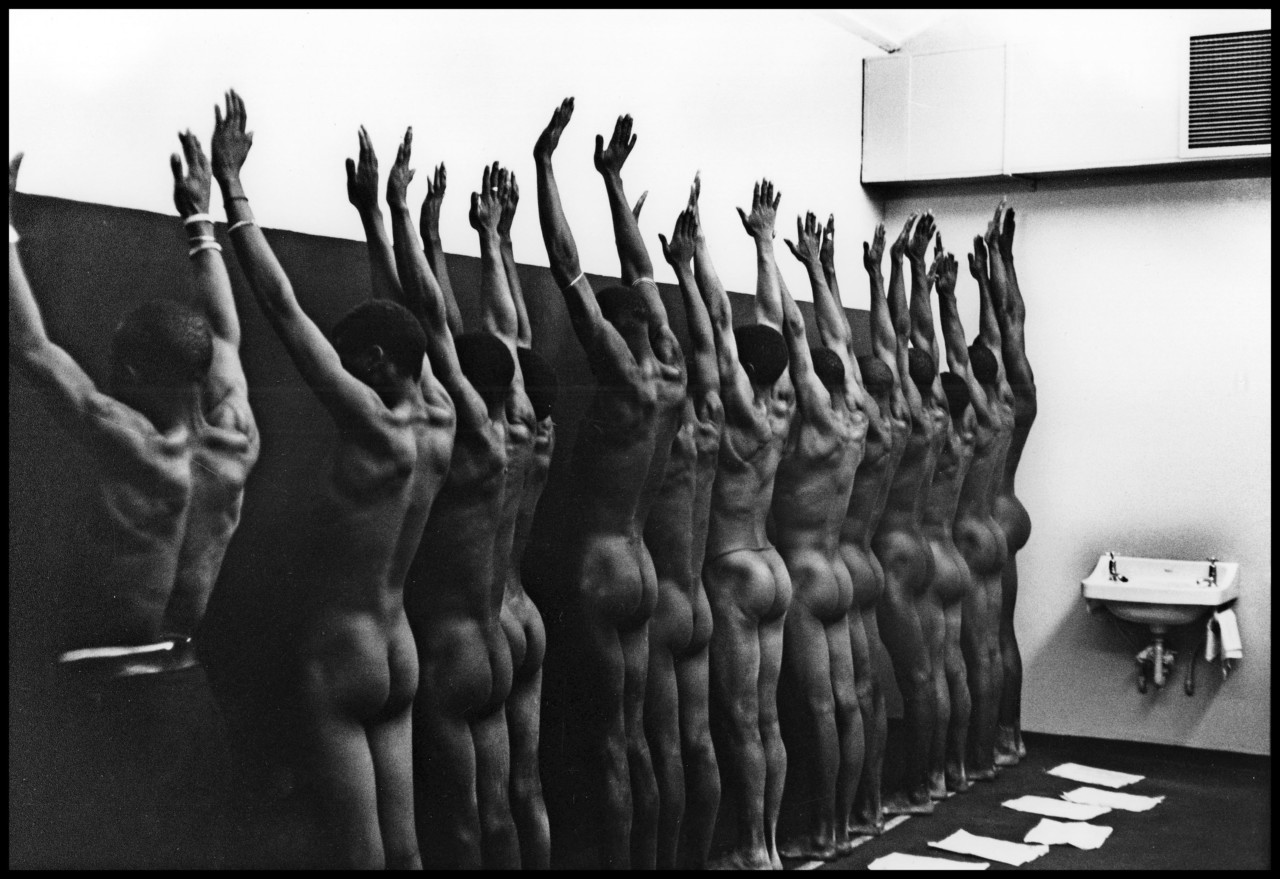

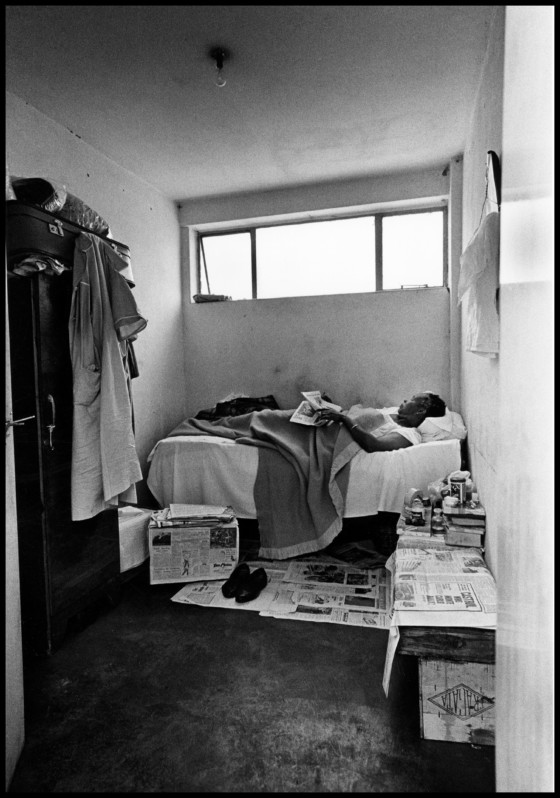

By 1966 it was becoming increasingly hard for Cole to work in South Africa. He took a lot of risks with some of the photos he shot, many of which could have resulted in life imprisonment – especially those taken in prisons or mines featuring people undergoing inhumane medical checks and other humiliations. Those photos were taken thanks to access gained by subterfuge.

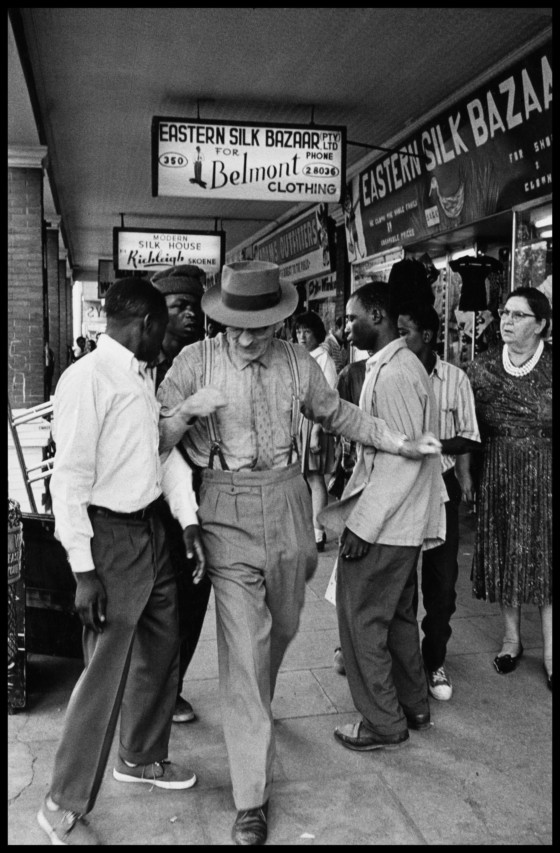

Apparently he learned from photographers such as Ian Berry, how to shoot fast from the hip, so that before he could even be spotted the camera would be gone and the photo captured. I suspect he also made the most of his colored status in terms of getting the access he did. South Africa was a very “essentialist” place, and at the time white people couldn’t fathom that he might share the same opinion as ‘blacks’, or that it would be odd to let a colored person witness their mistreatment.

He had been arrested a number of times by the mid-60s, notably during a story he was shooting involving the mugging by black South Africans of a white man – some say this was the catalyst for him leaving. The gang were arrested, and the police knew Cole had photos of the muggers and knew their names, but he refused to inform on them. On top of that, Cole had photographed an off-duty white policeman socializing with black women, which antagonized the police. He was stuck.

He was by this time concerned about spies and had suspicions about other ‘journalists’ working around him. There was supposedly a Yugoslavian journalist working in the same office, who he was told in confidence was actually a South African policeman. Another key factor, I think, in his leaving was that he really wanted to make the book, which he couldn’t have ever published in South Africa. He knew that. In 1966 he got out, getting a passport by saying he was going to Lourdes on a pilgrimage – being a devout Catholic, and colored, it worked. He left, taking with him the negatives that would become House of Bondage. He had taken the initiative to send some of his negs abroad to friends, such as Joe Lelyveld.

Cole knew about Magnum, as is clear from his writing which mentions Magnum photographers and their books, and he likely saw kindred spirits in the depth of their work. On arrival in Paris he sought out Magnum photographers and he met Marc Riboud, who didn’t have time to see him, but recommended he went to London where he met with John Hillelson, the UK agent for Magnum in the days before there was a London office.

Hillelson saw the House of Bondage work and was amazed, immediately calling Magnum’s Paris and New York offices, telling them they had to try and get publishers for the book. The Sunday Times bought it right away and published it. LIFE took the work on in America, along with other magazines around the world.

House of Bondage was published in New York in 1967, and a year later in London. It was banned in South Africa where people might have thought of Cole as the guy who took popular magazine photos, if they thought anything of him at all… knowledge of his work was minimal. He was far better-known in Europe and among South African exiles.

House of Bondage was the first way for a lot of people to actually understand what was going on in South Africa. While the anti-apartheid movement was getting into full swing at the time, most people had in general been turning a blind eye to what was happening in the country. There was very little visual information coming out of South Africa, and the book changed that. House of Bondage and the subsequent serializations in the new color supplements and magazines around the world brought apartheid into the public visual consciousness.

It seems he was never totally happy with the book, which is something we have to piece together now from what evidence we can find in his notes and letters. I suspect he wanted to show more of the real, day-to-day experience of living in South Africa. But the book that was published is very much about black South Africa’s relationship with white South Africa – it’s about apartheid, and is a prowling and growling indictment from beginning to end. It is totally politicized, but I think he wanted more than that, I think he was thinking of a book with more narrative and context. That’s what I feel he wanted, but the world didn’t want that. Every image in the book is an accusation.

"House of Bondage brought apartheid into the public visual consciousness"

-

Cole was, from a young age, very much like a classic Magnum photographer: he had a clearly defined view of how his work should be judged, and the prism it should be seen through. To me, he seems most similar to someone like Eugene Smith in that respect. Cole would berate people if they said he was the ‘best black photographer’ in the world – he didn’t want that, he wanted to be the best photographer, full stop. That caused some ructions at the time with white photographers thinking he was an uppity black man, and black photographers thinking he was belittling them by not settling for their level of success. He was in a tricky situation professionally.

With the book finally published the Ford Foundation gave Cole an assignment – they wanted him to do a long project, up to three years in length. Essentially the brief was, ‘do House of Bondage in the southern United States’. I can’t imagine what that was like for him. It’s one thing to move people out of their comfort zone, to try and get photographers to gain experience, but sending a 23-year-old black South African who’s not been in America long to the Jim Crow South to do a project titled something like ‘The Negro in the Country’?

Many great photographers are effectively asked to reproduce their best and most passionate work again, but focused on a different aspect or location, and this is where Cole may have struggled. All of his professional life, Cole had lived, breathed and worked on the struggle against apartheid – a system and life he knew intricately. Applying this depth and passion to another subject, however similar it may seem, is not easy and many have failed. This is often why I see a professionalism with Magnum, and other in-depth documentary photographers, in the ability to apply depth to stories they may not have the same level of passion for. Reading some of Ernest’s notes so far, he did not see the Civil Rights struggle as his own, which was maybe a mitigating factor in his later demise as a photographer.

The second part of the Ford assignment was about ‘the Urban Negro’. There’s thousands of shots of New York in the recently found negatives which may be part of the Ford commissions. There was a real lack of understanding of what he could do. House of Bondage was ten years work, expecting him to be able to do something like that, from an outsider’s perspective, without understanding the narrative? It was never going to work.

And it didn’t. From the small amount of editing we’ve performed with the New York pictures, my first impressions are of a guy who’s enjoying being in a new city, discovering new people with new attitudes, even if his notes betray sarcasm toward some of the experience. He was clearly interested in aspects of New York life that were taboo in apartheid-era South Africa. There are plenty of pictures of racially mixed couples, anti-government protests and plenty of pictures of the burgeoning porn industry – it feels like the era portrayed in the recent TV series, “The Deuce”.

Trying to piece together Cole’s life becomes a lesson in garnering fact from fiction based on anecdotal testimony. Other photographers who met Cole around this time say he started hanging out with ‘a bad crowd’, but I take that with a pinch of salt. What’s a bad crowd? He was probably mainly hanging out with African Americans and Africans living in America, what else would he have done? He was unlikely, having lived under apartheid, to stroll up to white people in order to make friends.

There was some skepticism among other photographers about his work, too. They were suspicious about the discrepancy between the quality of his South Africa work and the material he was making in America. He fell out of favor, and probably realized it. Also, the professional media world in New York is not the most forgiving place for newcomers or upstarts. For a shy man to be associated with the greats of documentary photography, being given seemingly dream assignments and having to carry them off, may have added pressure on the homesick Cole. He may have enjoyed NY life, but he always wanted to go home eventually.

We understand that he applied for a South African passport at one point, and was denied. From that point on he knew that he would probably never go home again. He was stateless and from 1969 started travelling to Sweden, where he worked with the Tiofoto collective, often. Cole had been strict-living when young, he didn’t drink in South Africa, which was pretty unusual among journalists there, black or white. But he started drinking in America.

Starting in 1972 Cole drifted away from photography. His life at that point becomes a mystery to us, but clearly he stopped working, and no longer controlled his archive. Then came the homelessness. That part of his life – well, we just don’t know much about it. It’s a matter of trying to piece together that story. What happened between his being in Sweden in the late 60s and his death in hospital from cancer in New York in 1990? We know he lived with an exiled South African doctor during his final months, but there are no more details at present.

For a man that, to me, documented the human condition in this powerful testament called House of Bondage, to then seemingly disappear is a tragic loss to photography. When people ask, “How has documentary photography changed the world?”, my cynical self turns to a quote from Chuck D of Public Enemy when he was asked if his music could change the world. “The only way my music will change the world is if I take my vinyl collection into the White House and smash a few people round the head with it”. In the same way photography will not change the status quo, but there are occasionally books – like Vietnam Inc by Philip Jones Griffiths and Cole’s House of Bondage – that do alter your perception of a subject.

"To then seemingly disappear is a tragic loss to photography"

-

When you think of the size of the Magnum archive, this addition is of course, in terms of quantity, tiny. But what’s really interesting is that within the Magnum archive there’s not much that we have in which – if we are really honest – the photographer is directly involved in what is photographed. Often, we have been photographing ‘the other’. That’s who we have often been, the middle-class photographer who comes in and looks at someone else’s life. And of course it may have been done with empathy, but Cole didn’t need empathy, it was his reality.

This makes the Cole archive very important from a photographic point of view, and from a Magnum perspective. It’s important in terms of who we are, and who we should be. It is about looking at the history of documentary photography and furthering it. It’s rare to have work like this where the photographer is not removed at all from the subject. This work is the photographer’s life.

In the next few months while we edit the archive, we hope to redress Cole’s lack of recognition for his role in the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, possibly to produce the House of Bondage that Cole actually wanted to make, to piece together the stories shot in the USA and lastly, to fulfil the dream of Leslie, Cole’s nephew, and the family, by having Cole finally get the credit he deserves for highlighting the injustices of apartheid.