Eve Arnold: The Unretouched Woman

We look over Eve Arnold’s body of work documenting women around the world, accompanied by her reflections on her path to becoming a photographer

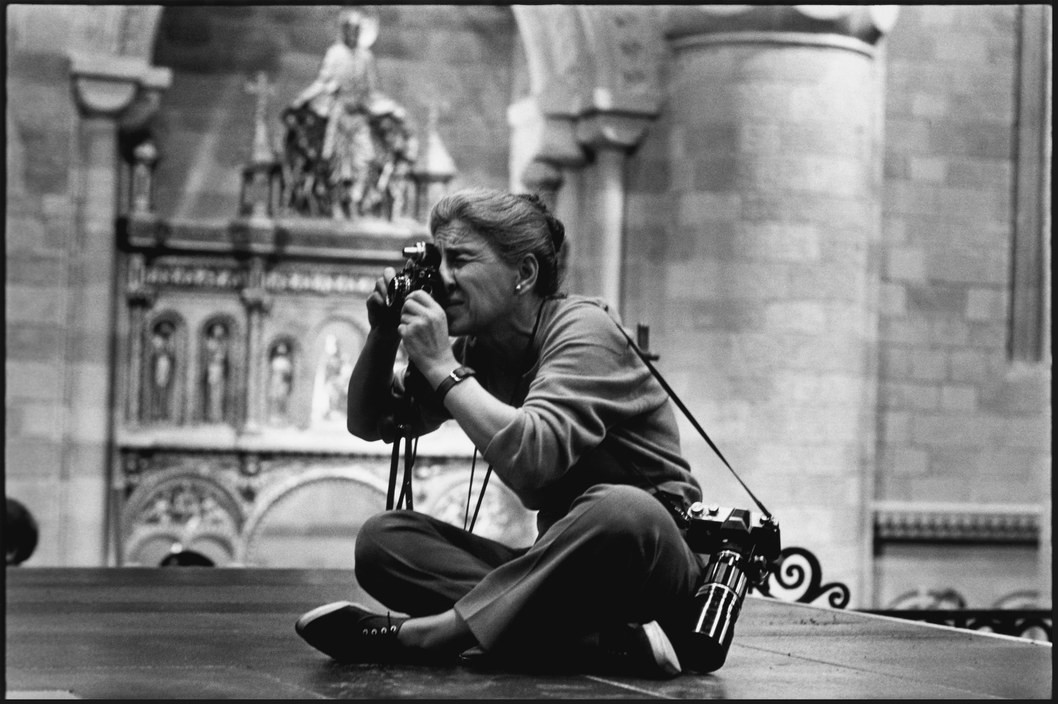

Eve Arnold, born in 1912, was the first woman photographer to become associated with Magnum Photos, in 1951. She became a full member of the collective in 1957. Born in Pennsylvania, the child of Russian-Jewish immigrants, Arnold initially entered photography through working in production at, and subsequently managing, a Kodak processing factory in New Jersey.

Her monograph, The Unretouched Woman was published in 1974, and brought together images from a quarter of a century of Arnold’s career. The book aimed to take an expansive look at the experience of being a woman, through a woman’s lens. The work was divided into several chapters, with photographic stories grouped together under themes – by region: on the USA, on South Africa; by topic: on the veiled woman, on monasticism; and included photo-essays on celebrities that Arnold had photographed using her uniquely intimate style: Marilyn Monroe and Joan Crawford.

Significantly, The Unretouched Woman was Arnold’s first book, published when she was 64. Despite Arnold’s many accomplishments which are evident in the book — working on assignments around the world and photographing stately individuals like Queen Elizabeth — her reflections reveal an initial reluctance to recognize herself as more than an amateur— “I lied and said I was a photographer” — telling both of her modesty and the difficulties of self-validation as an artist.

The book raises vital questions around the barriers that lay between women and their actualization as artists, photojournalists and professionals, both in the 20th Century and now. Here, we present an extract from Arnold’s text in which she provides valuable insight on her early life, her atypical entry into photojournalism, joining Magnum, how her work was perceived, and experiences of working on assignment.

This is a book about how it feels to be a woman, seen through the eyes and the camera of one woman—images unretouched, for the most part unposed, and unembellished.

Twenty-five years ago, when I became a photojournalist, I was looked on as someone apart—a “career lady,” a “woman photographer.” My colleagues were not spoken of in inverted commas; they were not “career men” or “men photographers”. I was not happy about it, but realized as have women before me that it was a fundamental part of female survival to play the assigned role. I could not fight against those attitudes. I needed to know more about other women to try to understand what made me acquiesce in this situation.

"I was looked on as someone apart—a "career lady," a "woman photographer." My colleagues were not spoken of in inverted commas; they were not “career men" or "men photographers”."

-

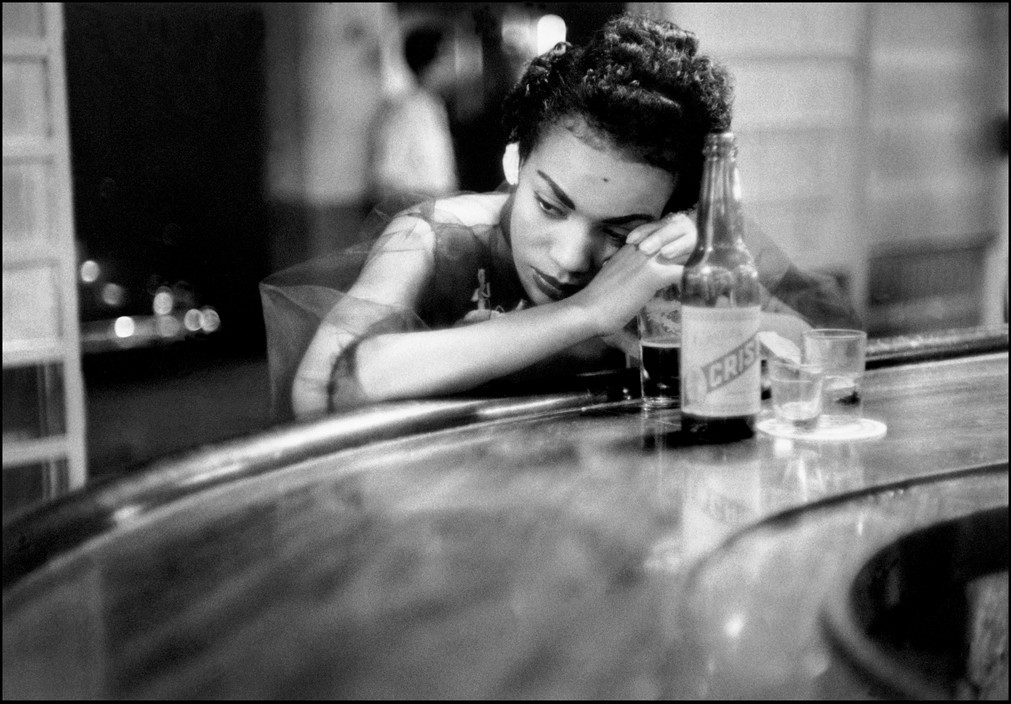

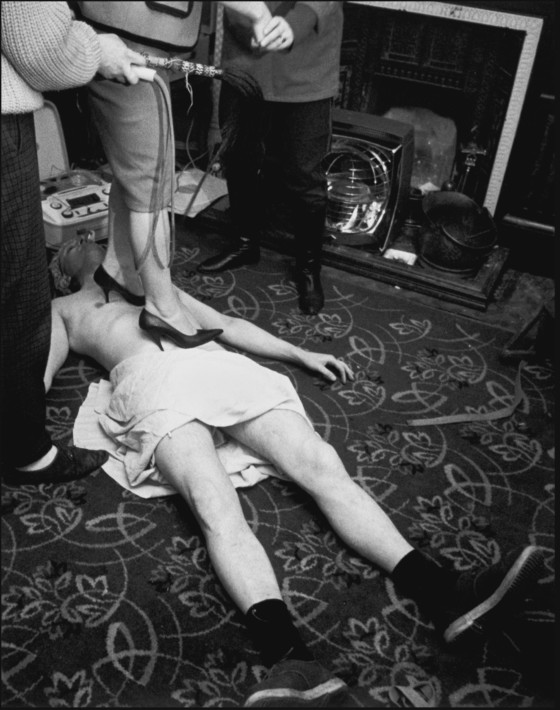

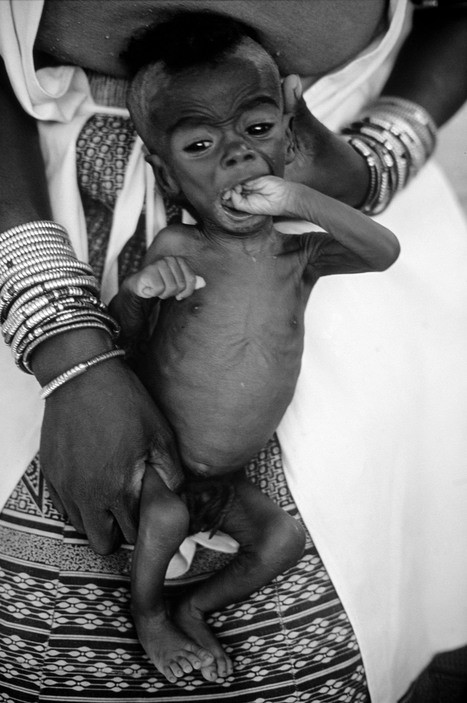

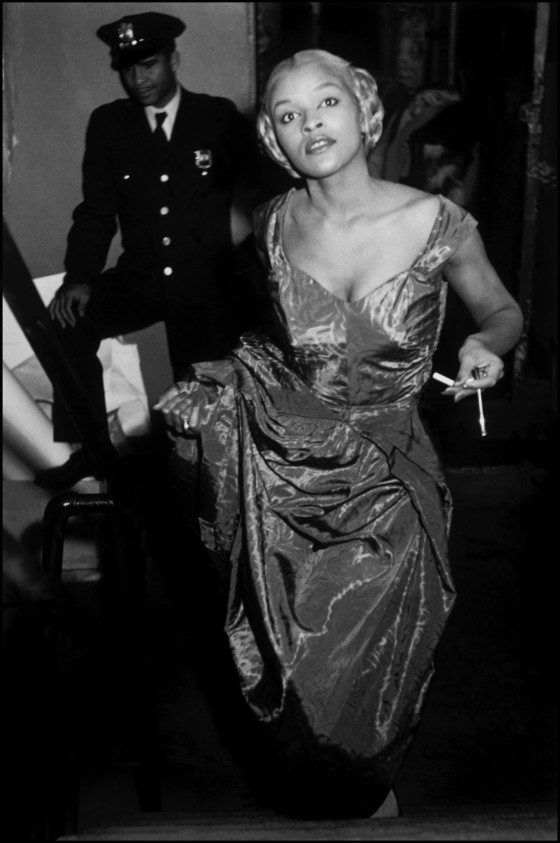

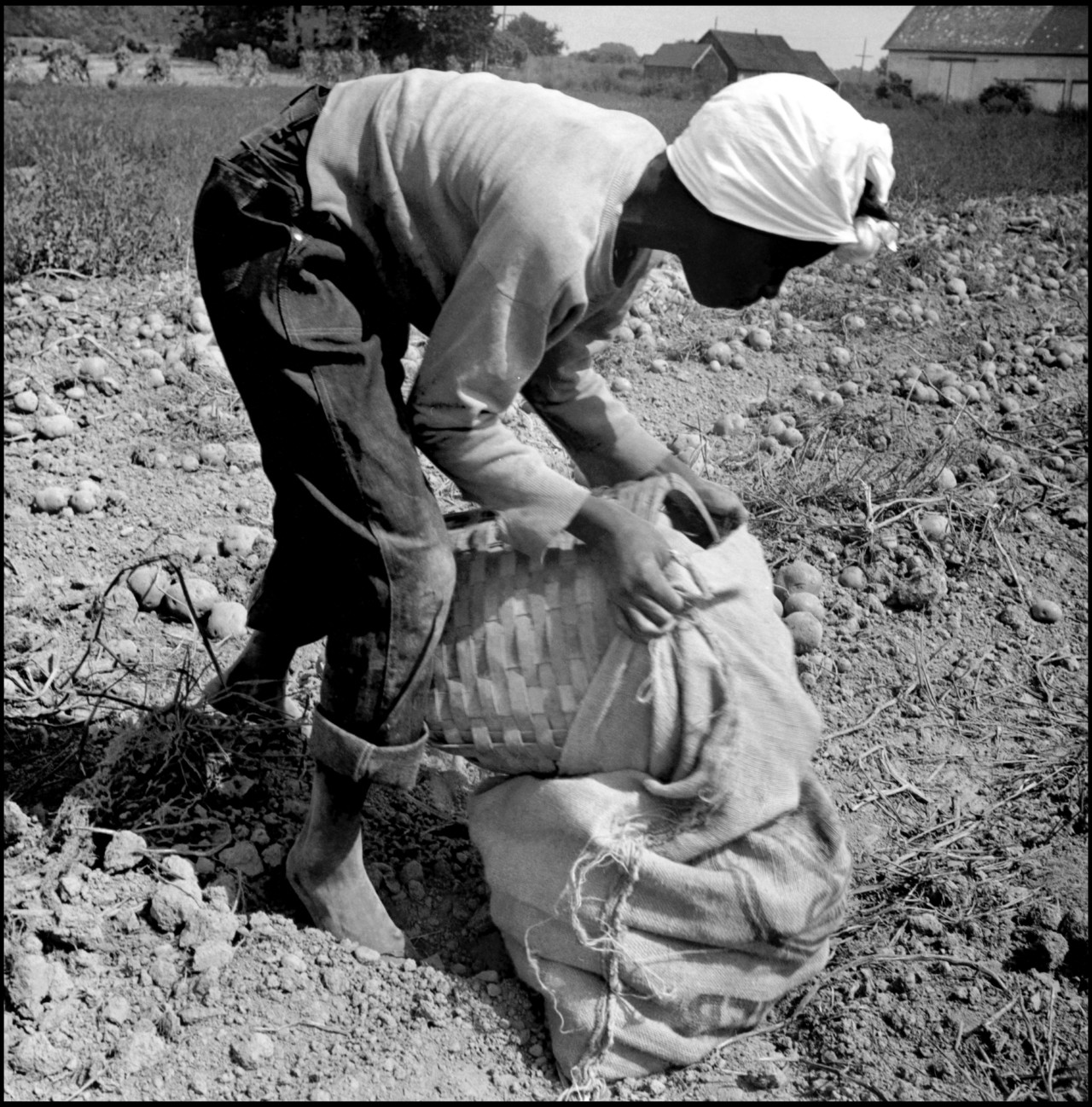

It was then that I started my project, photographing and talking to women. I became both observer and participant. I photographed girl children and women; the rich and the poor; the migratory potato picker on Long Island and the Queen of England; the nomad bride in the Hindu Kush waiting for a husband she had never seen, and the Hollywood Queen Bee whose life was devoted to a regimen of beauty care. There were the Zulu woman whose child was dying of hunger and women mourning their dead in Hoboken, New Jersey. I filmed in harems in Abu Dhabi, in bars in Cuba, and in the Vatican in Rome. There was birth in London and betrothal in the Caucasus, divorce in Moscow and protest marches of black women in Virginia. There were the known and the unknown—and always those marvelous faces.

I am not a radical feminist, because I don’t believe that siege mentality works. But I know something of the problems and the inequities of being a woman, and over the years the women I photographed talked to me about themselves and their lives. Each had her own story to tell- uniquely female but also uniquely human.

Themes recur again and again in my work. I have been poor and I wanted to document poverty; I had lost a child and I was obsessed with birth; I was interested in politics and I wanted to know how it affected our lives; I am a woman and I wanted to know about women.

I realize now that through my work these past twenty-five years I have been searching for myself, my time, and the world I live in.

I am an American. My parents came to the United States to escape persecution. Although they were both too intelligent, my father too sophisticated, to believe the mythology that in America the streets would be paved with gold, still they were not prepared for the daily struggle they had to endure. What made their lives and possible was the dream their children would have all the comfort and ease that they had never had.

I was always skeptical of future pie-in- the-sky, but I remember as a child sitting on the grass with my sisters and brothers (there were nine of us) through the soft summer evenings and listening to my father talk. He and my mother would reminisce about Russia and sing the revolutionary songs of their youth. He was a socialist and he talked about a world in which people would no longer have to wear out their lives to earn their bread. He always ended with the same sad words: not in my lifetime but perhaps in the lifetime of my children.”

My father was an educated man; my mother had had just enough training to write a laundry list, and to read the romances in the Daily Forward. My father wanted more than this for me. We had endless discussions. He suggested subjects, and books for me to read. When I was sixteen he read the Song of Songs with me in the original Hebrew.

Each day I had a different idea of what I would become: a writer, a dancer, a doctor. I decided I would study medicine and went to night school. Then a friend gave me a camera. Together we photographed the usual amateur delights— drunken bums sleeping in the Bowery, sun glinting off rope, texture of paint peeling off walls—and our Bible was the Kodak manual. I left school and went to New York. When people asked me what I did, I lied and said I was a photographer. The lies paid off. I got a job in a photo-finishing plant which employed 1500 people. It was at the end of the war and employees were hard to come by. Although I was very young, in six months I was production manager; at the end of the year I was plant manager and set up a second plant in Chicago.

I learned a great deal about photographic quality control, and continued taking pictures—the same “happy snaps”.

I had married during the war, and when my husband returned from the army, I left my job and stayed home to have a child.

Just as I had gone on with the myth that I was a photographer while I had actually been a high-priced and successful executive in the photo-finishing plant, I kept it alive when I became a housewife. My husband was irked by my misrepresentation of myself and kept urging me to go on with my photography. Two weeks after the baby was born, I picked up my camera and started photographing on the streets. But I had no direction and not a clue as to what to look for. We decided that I should take a course at the New School for Social Research given by Alexei Brodevitch. I did not know that it was filled with professionals who wanted to get assignments from the master, who was the Harper’s Bazaar art director, and with amateurs who hoped that some of the glory would rub off on them. The first evening, Brodevitch said in his broken English with its Russian accent: “Is Socratic method—will all learn from each other and from work have done for this class. Did anyone bring any photographs that we can look at?”

In a misguided moment, I had put together a bundle of my best camera club pictures. I realized the moment I entered the class that I was no match for the other people there. I was determined not to show them my pictures, but a friend who was sitting next to me grabbed the envelope (he had seen me putting the pictures together when he came to pick me up for class), and waved them at the teacher. I hadn’t the presence of mind to handle the situation. Brodevitch opened the envelope and held up picture after picture for inspection and criticism. The group was brutal. I felt flayed alive, but what came through to me was important. I learned more that night about the meaning of a photograph than I have learned from anyone since. It was my true start.

[…]

I started groping around for a way to work. I needed an agency that believed in what I was trying to do and that would handle my pictures. I was lucky. The international picture cooperative, Magnum, had started in Paris and was about to open a New York office. I went to see them. Being a woman helped. I was to be their token American woman stringer. I was in prestigious company indeed. The group had been founded by Cartier-Bresson, David Seymour, George Rodger, and Bob Capa. It was based on a simple idea. The copyright belonged to the photographer, not to the assigning publisher, as had been standard practice. This made an enormous difference. The group had some control over who used their work, how it was used, and what was said with it.

When Bob Capa saw my photographs for the first time he said that for him —metaphorically, of course—my work fell between Marlene Dietrich’s legs and the bitter lives of migrant potato pickers. I wonder if he knew how close to the mark he was about me.

I want to deal with the “migrants” part first. As a second-generation American, daughter of Russian immigrants, growing up during the Depression, the reality I knew well was poverty and deprivation. So I could identify easily with laborers who followed the potato crop north along the Eastern seaboard, settling in each new area as the harvest was ready for them.

Now, about Marlene’s legs—metaphorically, of course. I also grew up with Hollywood movies. Although I was a reluctant host to their imagery, I could not deny their impact on me and on other women. They affected the way we saw ourselves and the way men saw us. The traditional still photograph was an idealized portrait. The subject was posed in the most flattering position, and the features were lit—eyes, lips, teeth, cheekbones, breasts, and in Dietrich’s case, legs—like so many commodities. Wrinkles and blemishes were removed by the retoucher. Everything that life had deposited was penciled out.

When I photographed Marlene recording the songs she had sung to the soldiers during World War II—“Lilli Marlene,” “Miss Otis Regrets,” etc.—I wanted the working woman, the unretouched woman.

The presence of the photographer changes the atmosphere the moment the subject becomes aware of the camera. It is, however, possible to minimize the intrusion. I thought that by working in an area I knew, with people I knew, I might learn how.

I started a study of the Davis family of Brookhaven township, Long Island, where I lived. They were descendants of early settlers and American prototypes: a postmistress, a justice of the peace, a lady who sold penny candy, a teacher who taught in a one-room schoolhouse, and a farmer who employed black migratory labor. They attended the Unitarian Church and were members of the Daughters and Sons of the American Revolution.

"The presence of the photographer changes the atmosphere the moment the subject becomes aware of the camera."

-

This was a personal project from which I learned, and what I learned I was able to apply to my assignments; so that I could take Mamie Eisenhower to an amusement park in Denver and photograph her looking at herself in a distorting mirror, or photograph an Italian immigrant family in Hoboken, New Jersey, and be asked by them, at the death of the husband and father, to accompany them to the undertaker to view the body. What I learned was not technique, but that if the photographer cares about the people before the lens and is compassionate, much is given. It is the photographer, not the camera, that is the instrument.