Partying in Post-Soviet Moscow

Anastasiia Fedorova speaks to Gueorgui Pinkhassov about documenting nightlife and youth culture in the Russian capital in the early 1990s

The 1990s is a highly mythologised decade in Russian culture. When we speak of the ‘90s, we speak of transition from the collapsed Soviet order to global capitalism, but also of a cultural movement of unforgettable force. The explosion of home-grown art, pop music, rave culture and fashion in a whirlpool of political disorder still reverberates through contemporary Russian culture and imagery, and has shaped many generations to come. Photographs taken by Gueorgui Pinkhassov in the1990s are a unique insight into the decade, and document the pleasures, risks and identity quest of the young nation.

“I joined Magnum when the Soviet Union was on the brink of collapse, at the end of June 1988”, Pinkhassov remembers. “In the beginning of August 1988 I ended up in Prague with a French journalist from Libération, documenting the 20th anniversary of Prague Spring. My second assessment was an earthquake in Armenian towns Leninakan and Spitak, which came as a shock. It looked more terrifying than a war: during air strikes only certain buildings end up destroyed, but there everything was in ruins.

After I shot for a French magazine Actuel in Moscow, and then for The New York Times, for a piece titled “Young Russia’s Defiant Decadence” written by Andrew Solomon. These photos I took for The New York Times are the beginning and the backbone of my perestroika archives”.

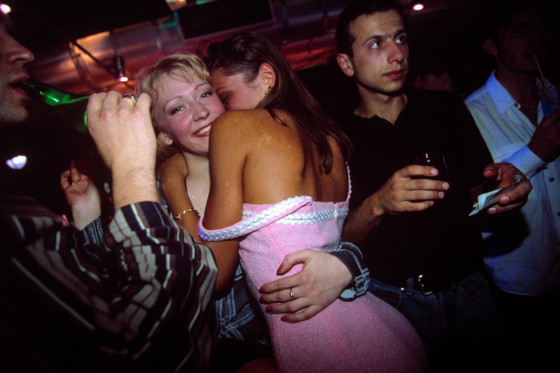

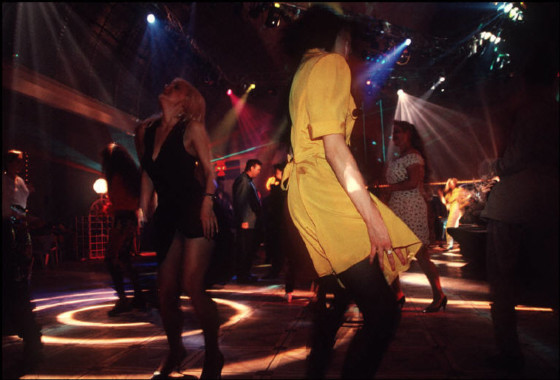

In the beginning of the 90s, Moscow saw the rise of nightlife, pop music, brand new alternative magazines OM and Ptyuch (which quickly became style bibles) and the art underground spilling into the free media space — all in the framework of the unregulated free market. In this new Moscow, indulgence had become a tool of exploration, a journey into an unpredictable and intoxicating future.

“As the New York Times correspondent, I met all kind of fascinating characters and subcultures, and felt the new powerful wave of youthful energy, vitality and passion which amplified social changes. I could compare it with the Russian avant-garde of Malevich, Mayakovsky and Eisenstein, which went hand in hand with the revolution in the beginning of the 20th century”, Pinkhassov says.

“It was like a tsunami. The previous generation was not able to protect their values of national unity and traditional social order — the tsunami was rising, flooding and overthrowing the unsteady and corrupt political power. To me, this was not unlike Europe in the 1960s, a conflict of generations, youth overthrowing their corrupt parents, yearning to come to power and proclaim new justice”.

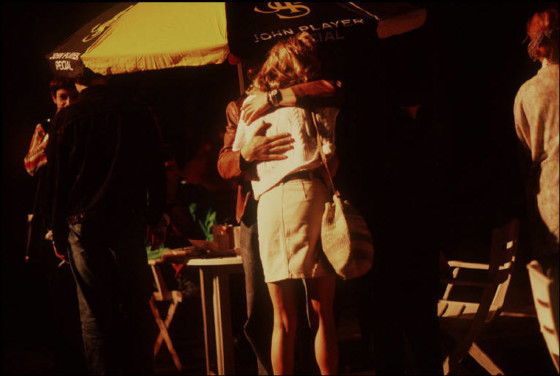

Gueorgui Pinkhassov was born in Moscow in 1952. Having worked as a photographer since the late 1970s, he moved to Paris in 1985. Belonging to both worlds on either sides of the vanished Iron Curtain, Pinkhassov produced a particularly poignant visual study of Moscow in 1993. Camera in hand, he followed the path of unknown pleasures to discos, casinos, hotels and gay clubs. Bathed in red, green and blue light, or in the midst of smoke and lasers on the dance floor, Pinkhassov’s subjects appear self-absorbed and static, stolen from the brief nature of the moment.

"I met all kind of fascinating characters and subcultures, and felt the new powerful wave of youthful energy, vitality and passion which amplified social change"

- Gueorgui Pinkhassov

Pinkhassov is widely known for his outstanding work with light, which can transform the most mundane scenes into nothing short of classic tableaux. His shots of a gay couple embracing at the disco or of a crowd watching fireworks in Red Square are indeed much more than just documentation — but an insight into global history and the nature of the Russian mind.

The photographer’s deep connection with art and film has always been a major influence in his photographic work. “With the deepest respect to all my colleagues at Magnum, I still have the most interest in its founders, particularly the personality of Henri Cartier-Bresson. I feel close to him because he, just like me, started as an artist, and wasn’t planning to be a reporter. The circumstances, and the passion to witness the world around him brought him to this role”, he says.

“I first heard the name of Cartier-Bresson from Andrei Tarkovsky. In the beginning of my artistic journey Tarkovsky liked my photographic work, but when we met in person he referred me to the example of Henri Cartier-Bresson, who I wasn’t aware of the time. ‘Time changes fast, Tarkovski said, it won’t always be like now, photograph while you have a chance’. I couldn’t ignore this advice from someone I considered my guru, although at the time I didn’t want to film reportage or look into private lives of other people. He was right, the world changed quickly. Who could have thought that the Soviet Union would disappear, and all the communications would change so quickly. When we look at these photographs today, we see this life as something exotic”.

Composing his portrait of the decade, Pinkhassov photographed creative pioneers who emerged in the 1980s underground, and each found a different path in the new world of the ‘90s. Artist Garrick Vinogradov is photographed at his studio; while Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe appears in a few shots from the lavish Metropol Hotel dressed as his frequent alias Marilyn Monroe; and musician Boris Grebenshikov poses against the wall in the bright sunlight with his daughter.

At the same time, Pinkhassov’s photographic quest was not limited to the nightlife and bohème. He captured the streets, squats, train stations, offices, and even the monetary stock exchange to reflect the greater complexity of the times. 1993 saw the White House burning during the constitutional crisis, food shortage in stores, critical level of unemployment and an overarching economic crisis. And although the viewer is aware of the underlying darkness, Pinkhassov’s images still have an air of nostalgia. Both the bright colours of foreign advertising and a striving for glamour would become a permanent fixture in Russian culture in the decades to come — but through Pinkhassov’s lens we still see newness, clarity and wonder.

Anastasiia Fedorova is a writer, curator, cultural critic based in London.