The Contradictions of Modern Japan

150 years on from the Meiji Restoration, we reflect on Magnum photographer Hiroji Kubota’s four-year survey of his home country

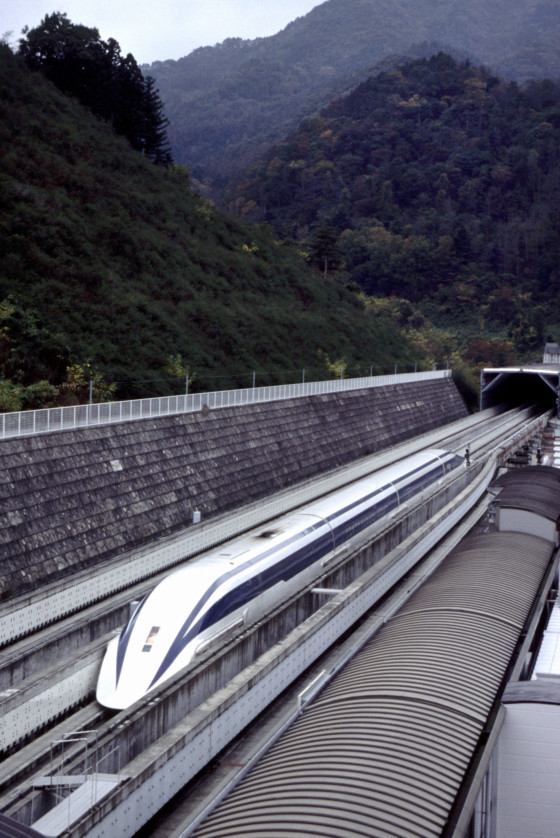

Modern Japan is at once seen as a pioneer of technological advancement and a steward of deeply held traditions. It is home to the fastest train in the world but also the oldest surviving sport; Sumo wrestling. One hundred and fifty years on from the beginning of the Meiji Restoration, which heralded the start of the country’s shift from being an isolationist, feudal society—purposely closed off from most the world—to an integrated, global one, the country continues its march towards a complex, contradictory future.

In 1999, Tokyo-born photographer Hiroji Kubota set about documenting the magnificent diversity of his country. He spent four years travelling its many islands, photographing ancient temples and Honda assembly plants, elderly women relaxing in Tazawako hot springs and children celebrating Shichi-Go-San festival with their very first kimono. Kubota photographed from the perspective of a Japanese-native but also one who had travelled the world.

“Thinking about how to do justice to Japan, I had decided to visit every one of its forty-seven prefectures at least twice, and to stay in the capital of each at least once. Many I visited far more times,” said Kubota. “I also opted to capture the seasonal changes in Japan, the weight of its history, the diversity of its handicrafts and arts, and the many facets of Japan’s modern economy.”

Kubota grew up as the second son of a successful fish merchant and lived through Japan’s disruptive war years; “They were cruel, hard times,” he said. But while the nation experienced intense misery, Kubota, only a small boy at the time, found lightness within the dark. With a young child’s innocence, he was exposed to parts of Japan that would influence his later desire to photograph them. He and his family travelled from Tokyo to the less dangerous Onjyuku in Chiba Prefecture, where he became “bewitched by the sea and the waves, and the sky”. Then, in Komoro in Nagano Prefecture, he was captivated by the mountains and forests. “In a way, for a small boy, it was an adventure,” he adds.

"Why did I wait until 1999, when I turned sixty, to turn my camera on my own country? I don’t really know"

- Hiroji Kubota

But in 1965 Kubota left Japan for New York. “For the next 35 years I spent most of my life thinking about Japan but travelling and taking photos overseas,” he said. “Why did I wait until 1999, when I turned sixty, to turn my camera on my own country, the country that sparked my interest in photography in the first place? I don’t really know.” Kubota knew he wanted to photograph Japan as far back as 1970 but spent the next three decades “consciously, subconsciously, and I guess, spiritually” preparing himself for this considerable task.

Kubota did most of his travelling in a four-wheel drive Toyota Corolla station wagon, taking advantage of the country’s extensive network of car ferries and occasionally the Shinkansen bullet trains. Japan’s infrastructure is perhaps the most tangible development since pre-Meiji times. During the mid 1800s, not only did the country have no trains, but roads were so crooked and bumpy that neither horses nor carriages could pass along most of them. There was often no alternative to travelling by foot or being carried in a palanquin. But now, as Kubota noted during his travels, “Japan’s railroads are the most advanced in the world.”

The railroads may run through the countryside but they form gateways to Japan’s most modern manifestation; the metropolis. The density of their architecture is captured in Kubota’s images taken in Kyoto, Tokyo, Nara and Osaka, which, he says were central to understanding Japan today: “the weight of its history and its possible direction in the future”. In Osaka, a futuristic looking eight-story shopping mall reveals Japan’s love of retail, while the aerial photos of Tokyo show the sheer scale of the country’s most populated city. Modern cultural activities are revealed in the high-tech pachinko parlours which, at the time, had an annual revenue of more than 10 trillion yen. “I would guess there’s not a city, town or village in Japan that doesn’t have one,” said Kubota.

Technology is the cornerstone of modern Japan and Kubota spent time photographing the work of companies such as Canon and Fujifilm, who are among the leading forces in their market. He visited Canon’s Tochigi factory and noted the extreme precision required to manufacture the “super-high performance” lenses. While the Tokaido Shinkansen—or bullet trains—which run at 320 KM an hour, are photographed in their sleek, futuristic splendour.

But as well as documenting Japan’s obvious modernity, Kubota was fascinated by the country’s rich culture, many aspects of which have remained unchanged for hundreds of years. In this way, he engaged with archetypes rather than stereotypes; familiar tropes of the Japanese aesthetic such as the painstaking precision of traditional artisans. As an insider, he refused the superficial, instead appreciating the experience and craftsmanship that produces such art.

“Gold and traditional lacquerware, bamboo tea ceremony whisks, pongee fabrics, shakuhachi flutes and ceramics: no words can do justice to their beauty, and to the meticulousness of the men and women who created them,” said Kubota.

But it was the profession most rooted in his personal history that ultimately held the most magic. “I guess it’s because I’m the son of a fishmonger, but I’ve always been more interested in fishing and fish markets than in perhaps any other facet of life in Japan,” he said. “I was always humbled by the dignity with which the fishermen dealt with their arduous working conditions.”

Though Kubota has photographed more than 40 countries, he says he enjoyed photographing in Japan more than anywhere else. “Almost everyone I met was very decent, hardworking, and grateful for their blessings. I’m not a nationalistic person, but after that experience, I can say: I’m proud of being Japanese,” he said. “I’m happy I was born in Japan. It’s an amazing country.”

Kubota’s diligent study of his homeland is revealing of both the country and the photographer. When he was a young adult, his grandmother told him: “Hiroji, time really flies fast!” Indeed, the country that first ignited his imagination as a boy has changed exponentially since. His journey across Japan convinced him his grandmother was right: “Time is short, and we should live life to the fullest.”