It’s Expensive to Be Poor

Hannah Price explores life and neglect in affordable housing for a family in Philadelphia. Interview by Danielle Ezzo.

It’s Expensive to Be Poor, a new series by photographer Hannah Price, reveals an intimate look into the lives of Lisa and her two children in Philadelphia, where Price is currently based.

The final edit of 55 images is the latest collaboration between Magnum Photos and Obscura. The full collection is now available to purchase as NFTs and can be viewed here.

In the edited extract below, Danielle Ezzo, a contributor to Obscura Journal, interviews Price on the systemic and economic issues that many face, the responsibility of using your platform for change, and how the power of text and image can work together to deepen narrative context in a visually-saturated culture.

Danielle Ezzo: Could you give us an overview of the project, explaining how and when you met Lisa?

Hannah Price: Right around the time that Obscura asked for a proposal, I don’t know where I was, I can’t remember how many months ago, but I just remember thinking about how expensive it was to be poor, in general, so I wrote this brief, concise proposal. Once it was accepted, I started searching on social media for a subject or subjects who were potentially affected by bills, or who were caught in a deep hole by not being able to afford their situation. I ended up finding lovely Lisa on this social page called No Gun Zone. She was frustrated in her living situation and her only choice was to get out of it on her own, by herself, without the help of outside resources.

"I wanted the freedom to take a deep, intimate dive into someone's story. I want to get readers closer to that experience emotionally and feel how difficult life is for underprivileged people. "

-

DE: It’s Expensive To Be Poor seems to be in direct conversation with your previous projects. I’m thinking of Semaphore specifically. Can you expand on this idea of signaling? What do you see as your role as a photographer in contributing to these representations of race, class, and identity?

HP: Maybe the signaling, in this case, is the text. Because I feel like that is the part where I share the intimacy of her story. What does it actually feel like to be poor? If you’re looking at those images, would you assume her to be poor? We see so much footage – as people and in a visual world – we kind of live on the surface of all these images. I try to also access what’s not visible and create points of entry for people to relate to.

What I’m trying to create specifically is access for Lisa. I’m trying to give back, the part that I want in sharing stories is the benefit of giving back. I set Lisa up with a crypto account and I was able to directly give her money from the profits of the NFTs. Being able to do that feels like a certain kind of influence.

DE: We’re inundated with images, so it’s just very easy for most people to be overwhelmed and not understand the gravity of what those images are trying to communicate. There’s something about being able to embed a story and elicit a deeper response from it.

HP: It was really cool working on this and just learning about NFTs in general. I also got to pay my research assistant this way too. She was like, “Oh, my God, now I can fund my projects.” I was able to pass it on, and then it was passed on again.

This is the first time I’m doing this and I want to facilitate change. Sometimes there’s only so much that we all can do. The change, for me, was the ETH that I gave her, but at the same time, as a single mother of two, the funds I gave her only helped her for a month. So I hope that the pictures and the text together on the blockchain will facilitate more long-term change.

DE: Can you speak to the line between exposure and subjugation, specifically when you’re photographing someone who’s in a vulnerable state?

HP: In the beginning, I’m upfront. I tell them who I am and give them resources and links to also read for themselves, of who I am. Then I give my subjects permission to stop me or tell me whenever they’re uncomfortable.

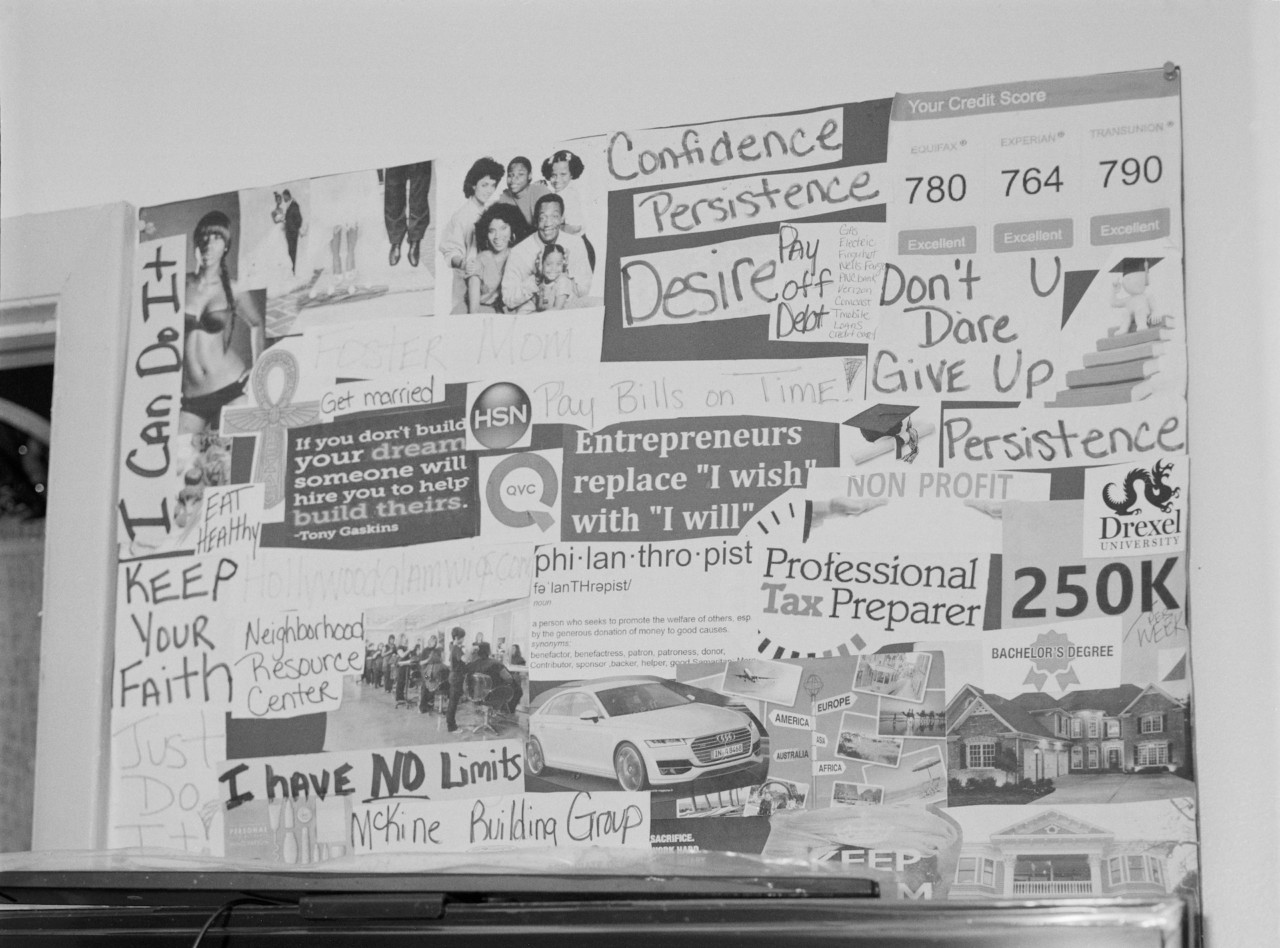

DE: Image #33 in the series looks like a vision board. Can you talk about that one?

HP: Yes, that was one of the first days. She was so frustrated about her environment that she needed that vision board above her bed. Then, she had another one with her boys as well. It’s what she wakes up to every day.

DE: You’ve said that you developed a friendship with Lisa in the process of photographing her, and the deep connection that you fostered has inevitably informed the way you photographed her. Can you walk me through how the friendship influenced your approach to making these images?

HP: I’m very consistent in the beginning: I try not to start photographing right away until I get full permission. Sometimes I don’t take the photo because I haven’t established that permission and comfortability yet. I want them to forget the camera is there in a way, but at the same time, know that they can tell me to stop.

With Lisa, our friendship just ended up being like any other real friendship. We would talk every now and then and check in with each other over text. Then, we’d make plans to photograph and then I’d come over, but then, you know, life is in the way, and as adults, things happen. There are times when she needed to express herself. Then there were other times when I did. So instead of making a photograph, we were kind of friends first. Recently, she invited me over for Easter, and even though I’m done photographing, we continue to hang out. I guess my approach is influenced by the intuitiveness of my process and how I go about getting those images during intimate moments.