“I can’t let go of the desire to believe in a society where things really will get better”

Jim Goldberg on his seminal work documenting the "Rich and Poor" of San Francisco

The representation of poverty is at once political and personal, revealing as much about society as it does about the person who documents it. But what is universal, is that the stories are never just about poverty; they are about powerlessness, prejudice, stigma, suppression and a myriad of other complex structures of suffering. As part of a new theme, we will feature Magnum photographers who have reported on those struggling every day to survive and will explore the difficulties of representing a much-ignored reality.

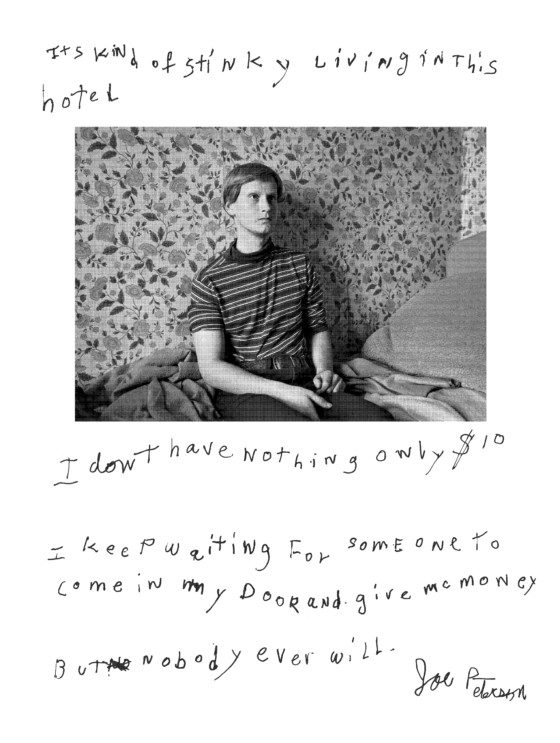

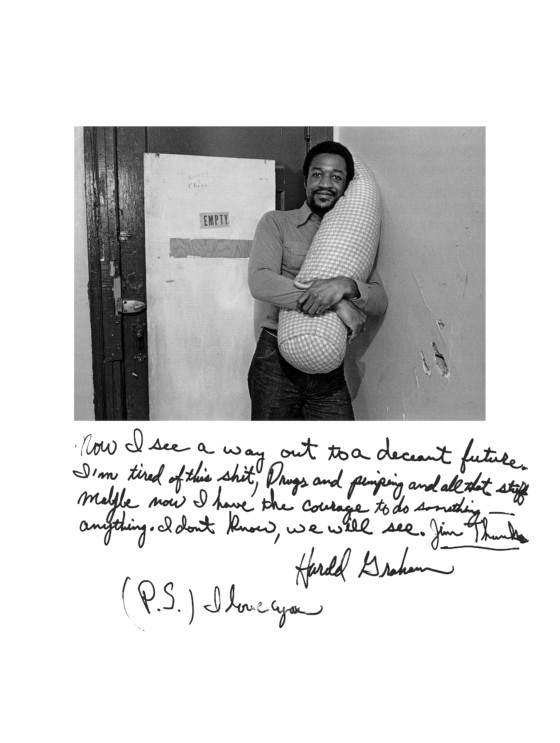

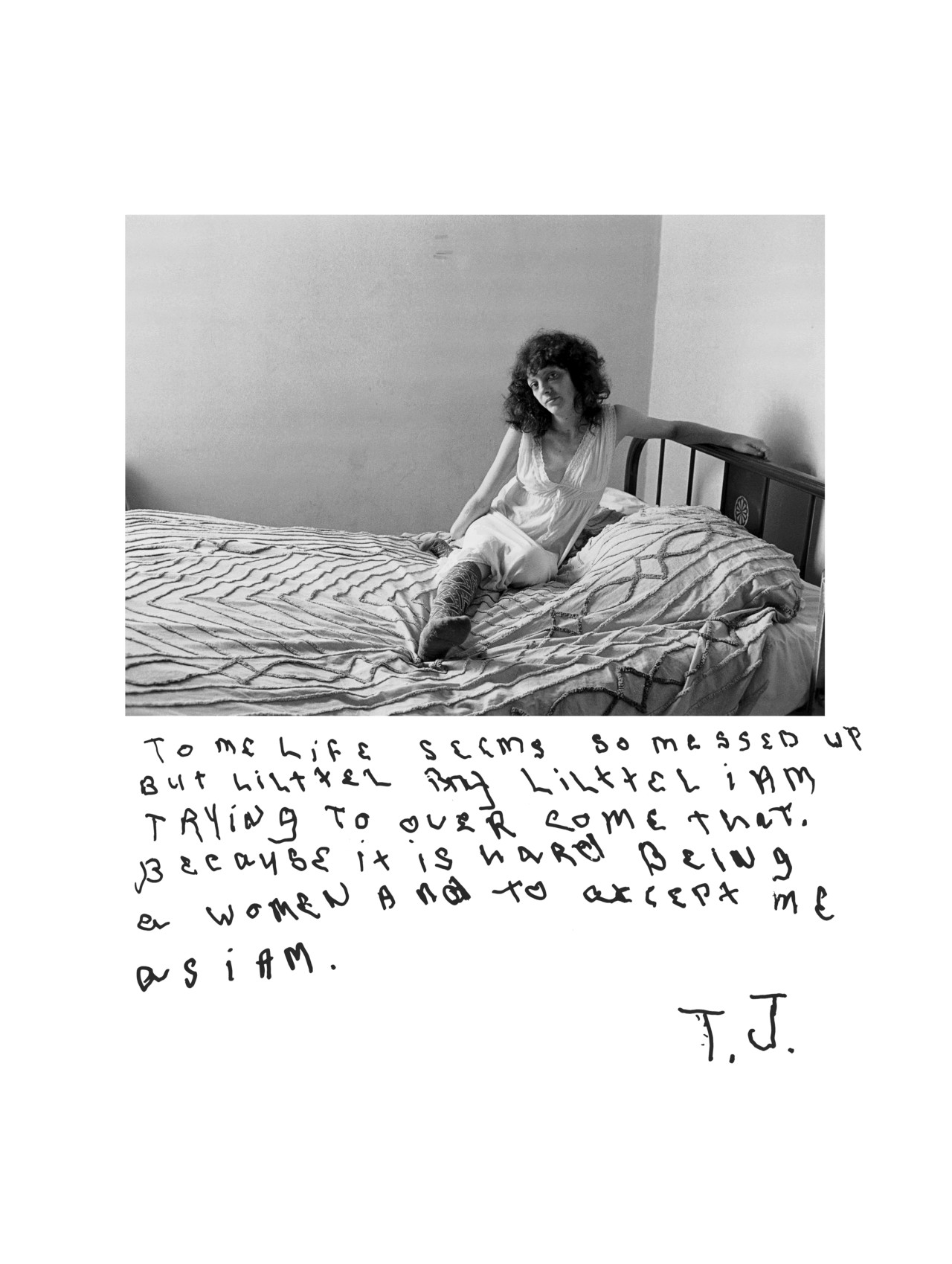

“It’s kind of stinky living in this hotel. I don’t have nothing only $10. I keep waiting for someone to come in my door and give me money but nobody ever will.” So wrote one young man named Joe, living in a single occupancy hotel in San Francisco in 1984. The open letter to no-one in particular is scrawled over a photographic portrait, which reveals the author to be a fair-haired, pensive boy, dressed in a striped T-shirt with a lost look of despondency on his face.

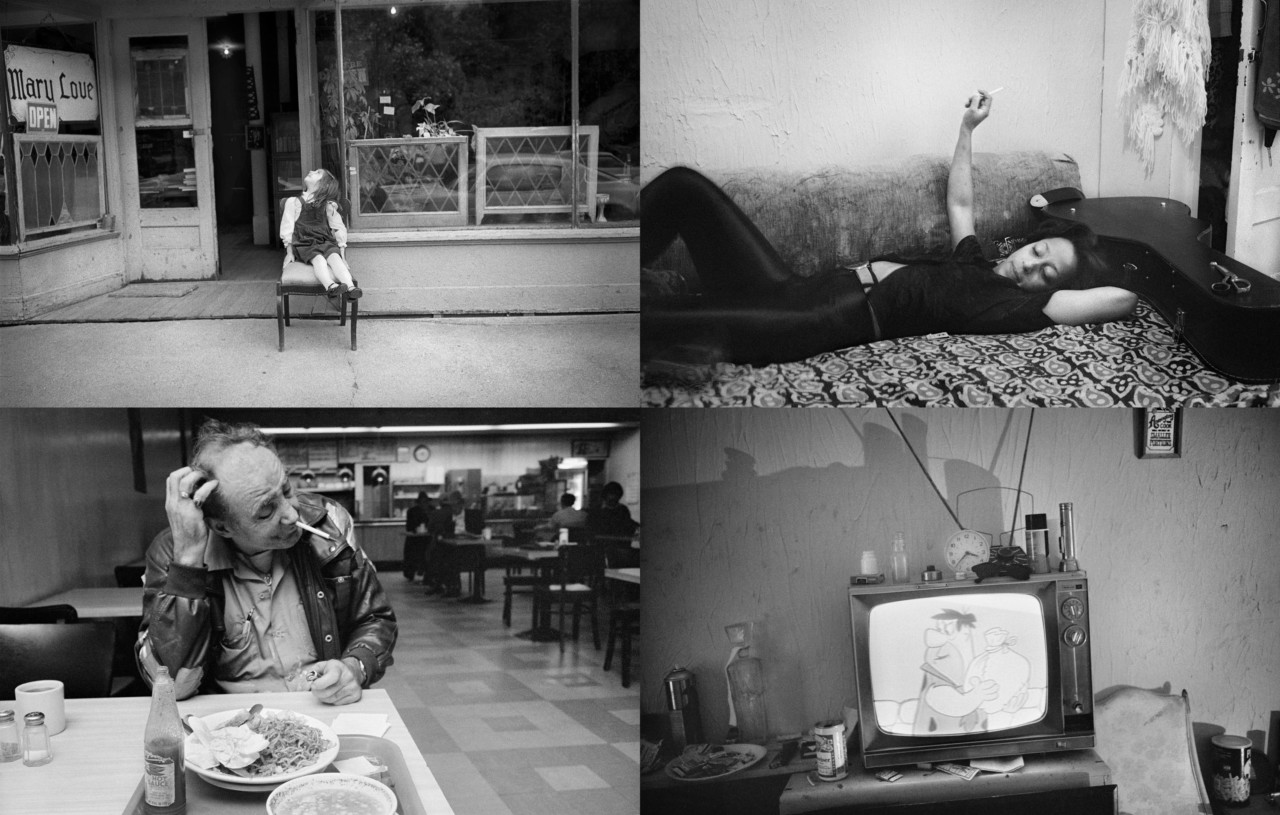

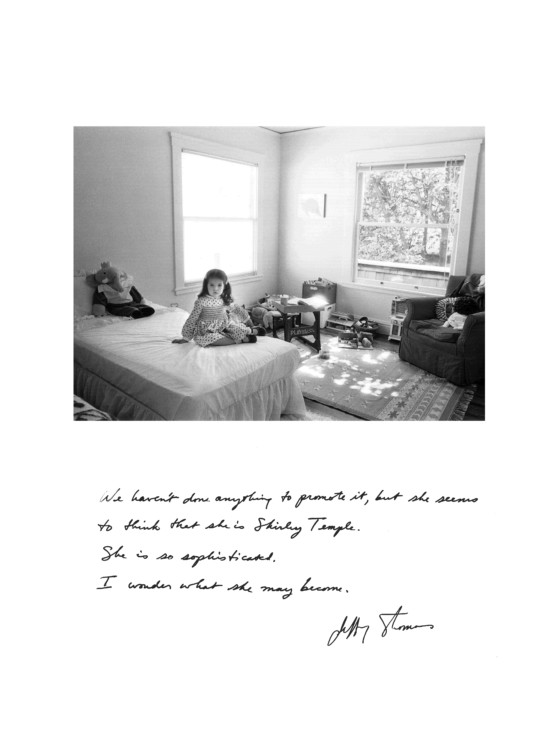

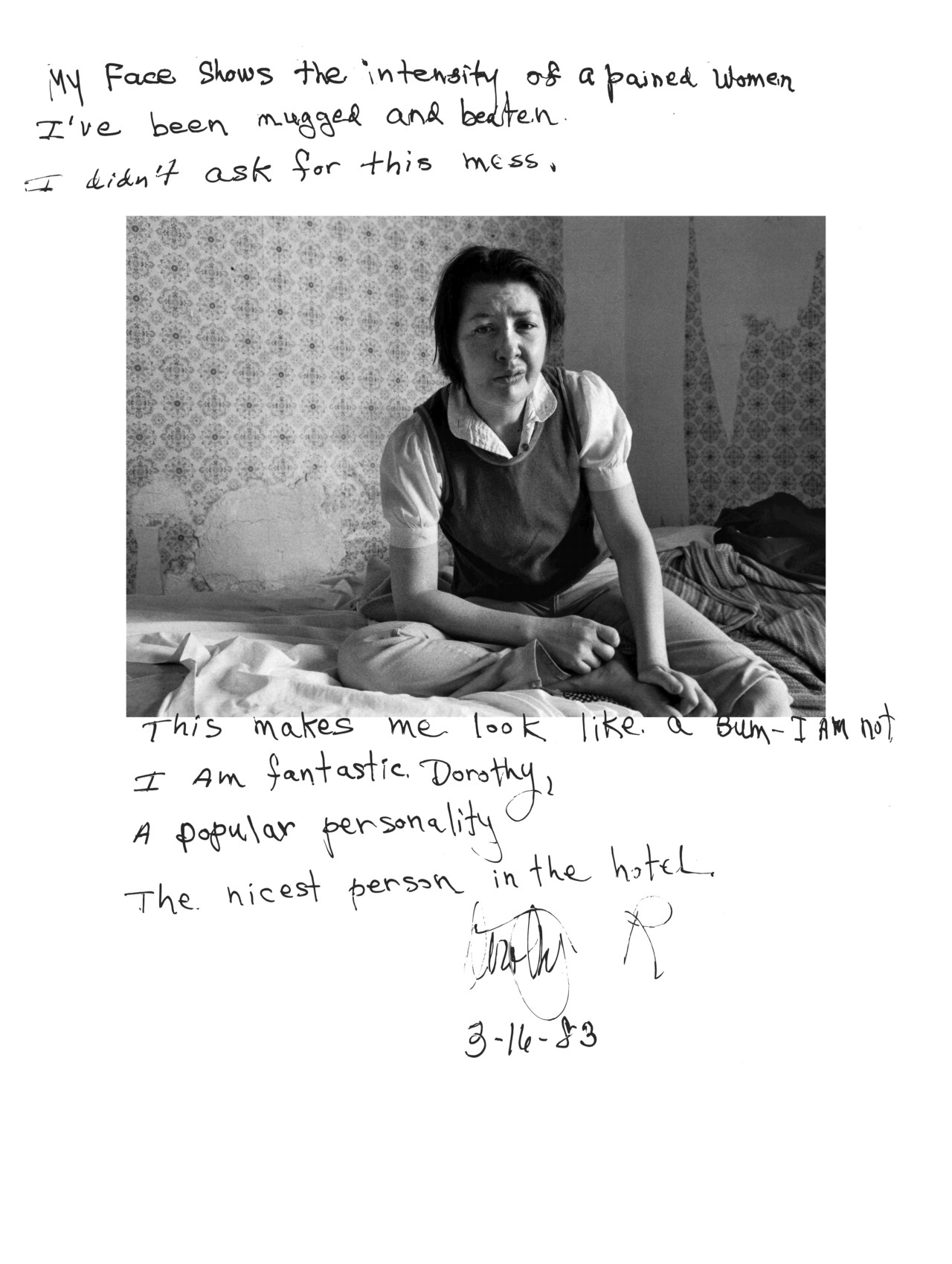

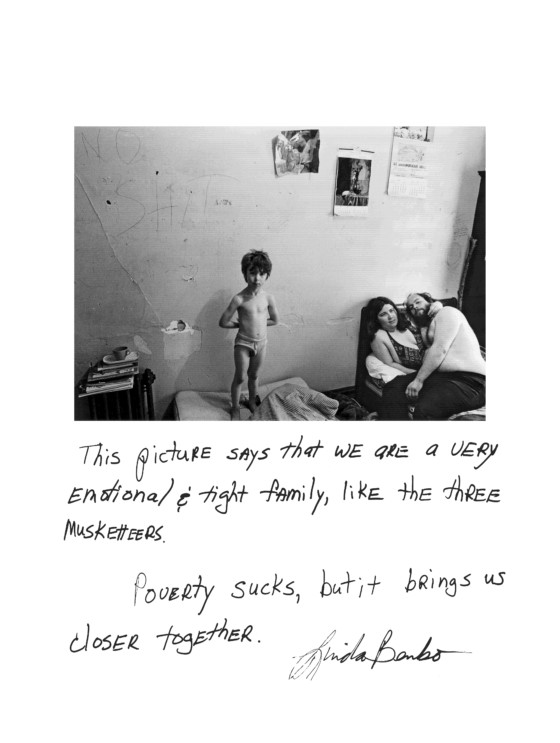

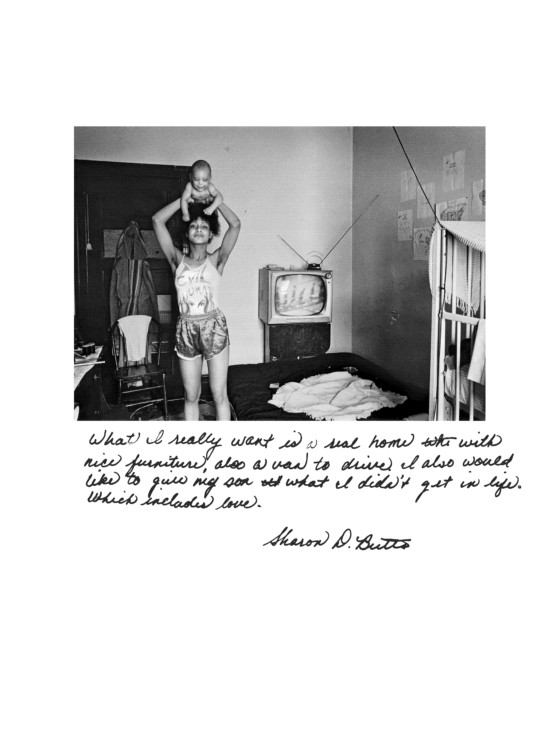

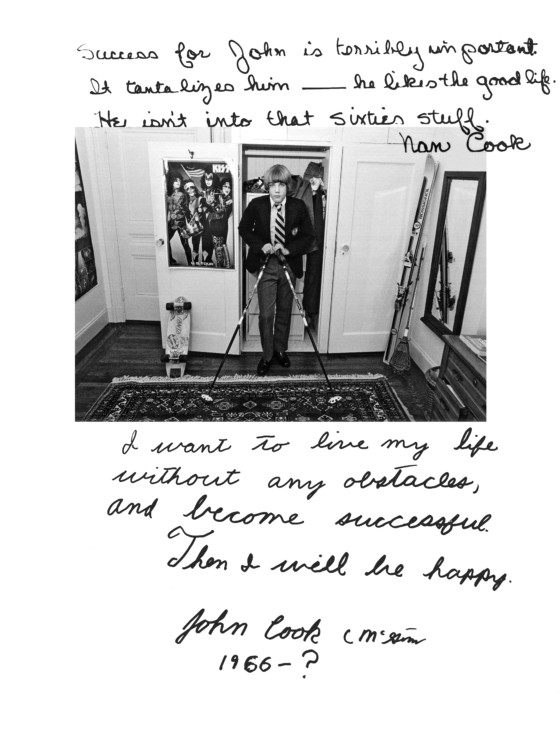

Joe was one of many who became the subject of Jim Goldberg’s seminal project, Rich and Poor. Created between 1977 and 1985, the photos and subsequent title leave little room for ambiguity. The wealthy and comfortable are juxtaposed with those who are struggling to see a bright future. All the pictures were taken in the same West Coast city but the difference in circumstances makes them seem worlds apart.

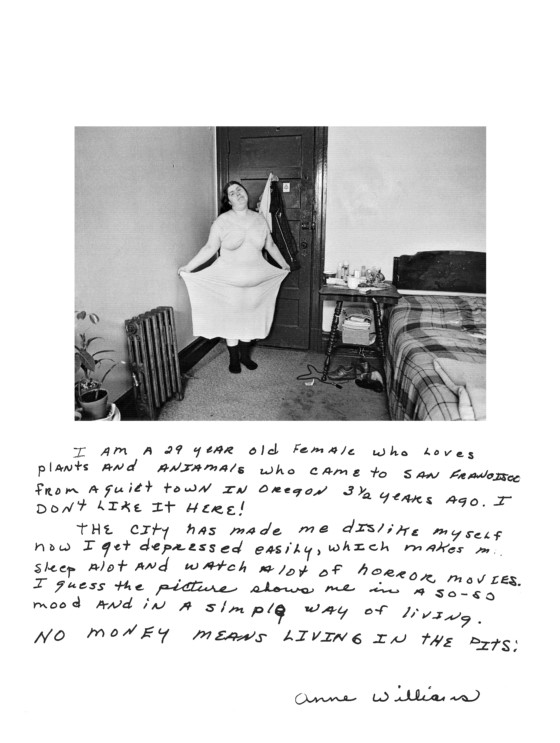

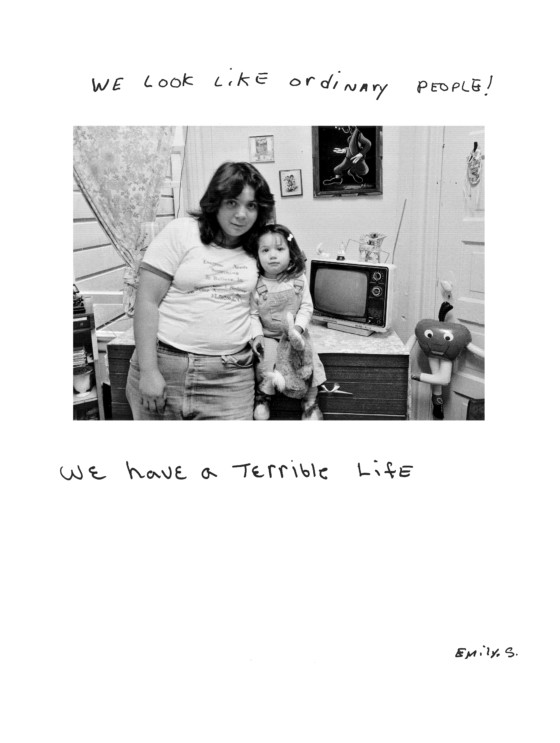

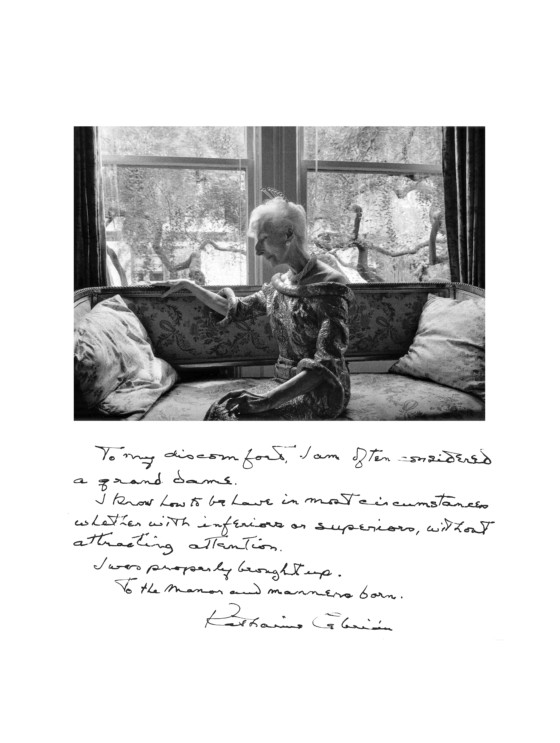

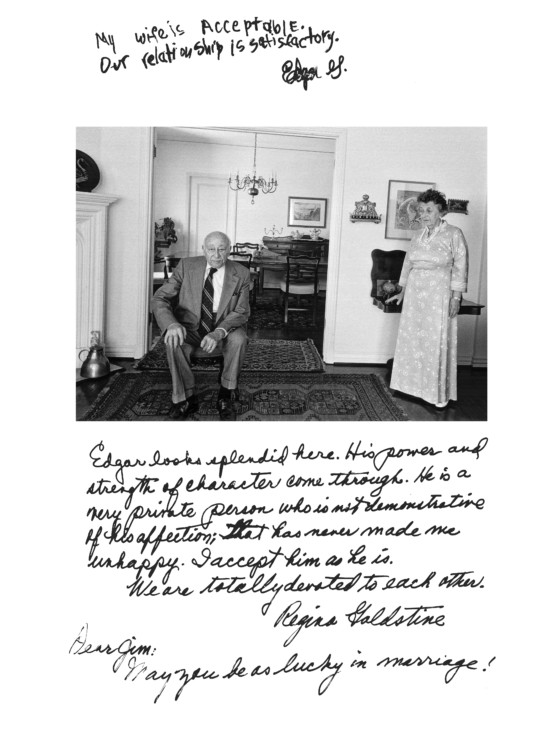

In the spirit of Studs Terkel’s oral history, Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do, Goldberg’s series passes the microphone to the subjects. They are invited to reflect on their portraits and the lives that they depict. Their accounts range from devastating edicts of hopelessness to affirmations of self-satisfaction. One man writes “I am doomed to be in this place, I have no future” while another woman comments “My life is luxurious and my taste is refined.”

"I have spent time reflecting on my boyhood in New Haven, and why I felt compelled to make Rich and Poor in the first place"

- Jim Goldberg

When tackling a topic as loaded as poverty, questions of ownership and representation abound. But in offering the subjects the chance to review their image and add a dimension of their own to the work, Goldberg gives them a stake in the narrative. Here, the text and images work as cumulative data, gathered over the course of eight years – historical testaments to lives as much as they are photographs.

Years later, Goldberg revisited the work for a republication of the book and in doing so, found his perspective had shifted: “I have spent time reflecting on my boyhood in New Haven, and why I felt compelled to make Rich and Poor in the first place. I have a more nuanced view now about what photographs can and cannot do to address economic disparities, but I remain fascinated by my original impulse to undertake the project, and by the assumptions of American exceptionalizm, picked up as a boy in New England, which suffuse the work,” he writes.

“We were taught back then that we were on a special path, and I think my outrage about the desperation of the poor – and the dissatisfaction of the rich – stemmed in part from my belief that they represented a derogation from that path, a veering off course that had to be rooted out and documented. And I believed, I really believed, that once people saw what was happening, then we, as a society, would fix it.”

Clearly, Goldberg’s youthful optimism has been dampened somewhat since the work was first published in 1985 – and it’s not difficult to see why. According to data from the U.S. Census’s American Community Survey, California has the second fastest growing income inequality in the country. San Francisco in particular stands out because it has become a hub for high-tech industries and a home to many of America’s highest-paid workers. Indeed, when cost of living is taken into account (it is 25% higher than the national average) a low salary for a family of four is calculated at $117,400. This is in stark contrast to the city’s growing problems of homelessness and open drug use.

“I’m less naive now, or at least I hope I am. I’m confronted daily by the fact that conditions for the ‘Rich’ and the ‘Poor’ haven’t changed much since the book was first published,” concludes Goldberg. “But I can’t let go of the desire, the impulse, to want to believe in a society where things really will get better. And, if nothing else, I hold out the hope that my photographs and all the people I met can at least still speak for themselves.”