Let’s Dance !

To celebrate Unesco World Dance Day, three Magnum photographers reflect on why the subject is of enduring interest

Is there anything more freeing than dancing as if no-one is watching? From the cheery gyrations on show in the Working Men’s Clubs of Britain to Senegal’s traditional and participatory Simb Gaïndé dance, the act of physical self expression is a unifying part of almost every culture. It is unsurprising then, that countless photographers have sought to capture this instinctual urge,

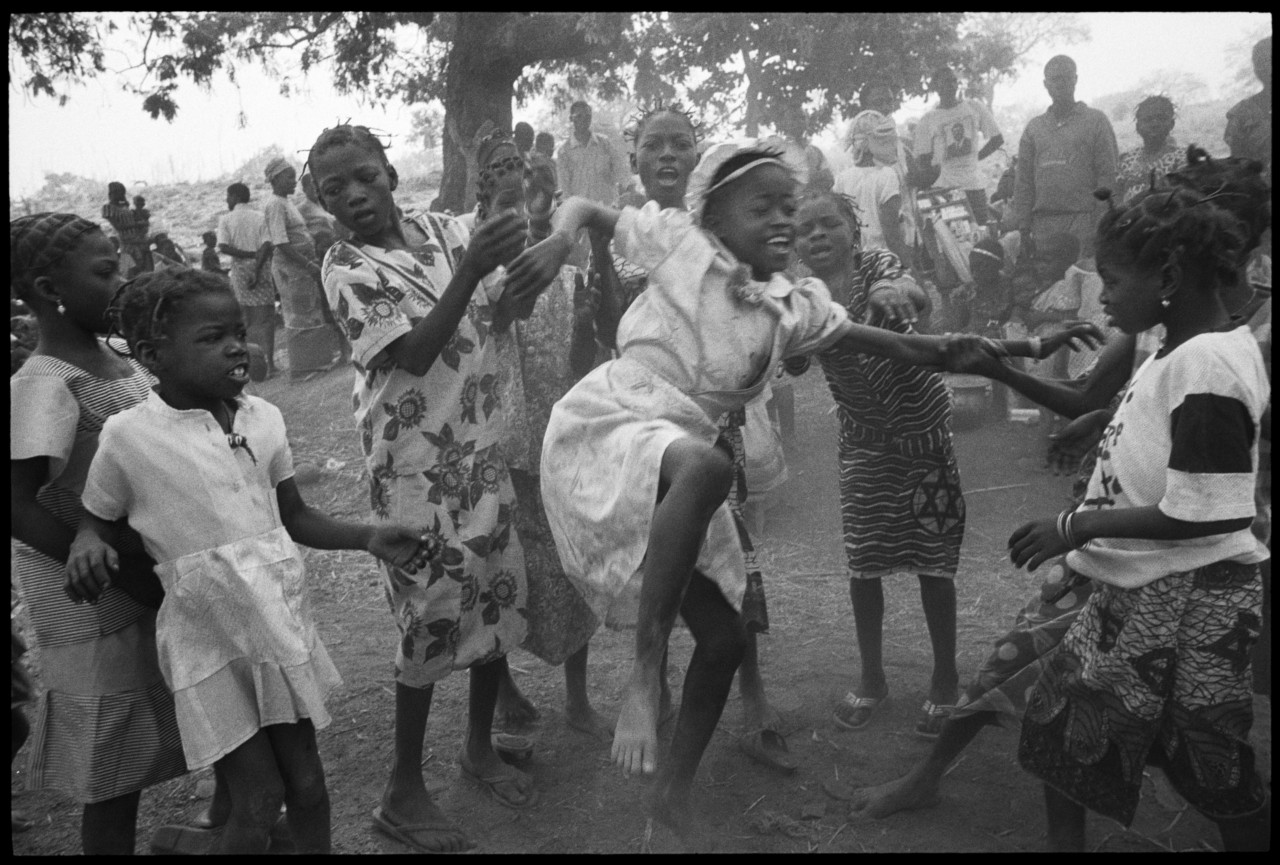

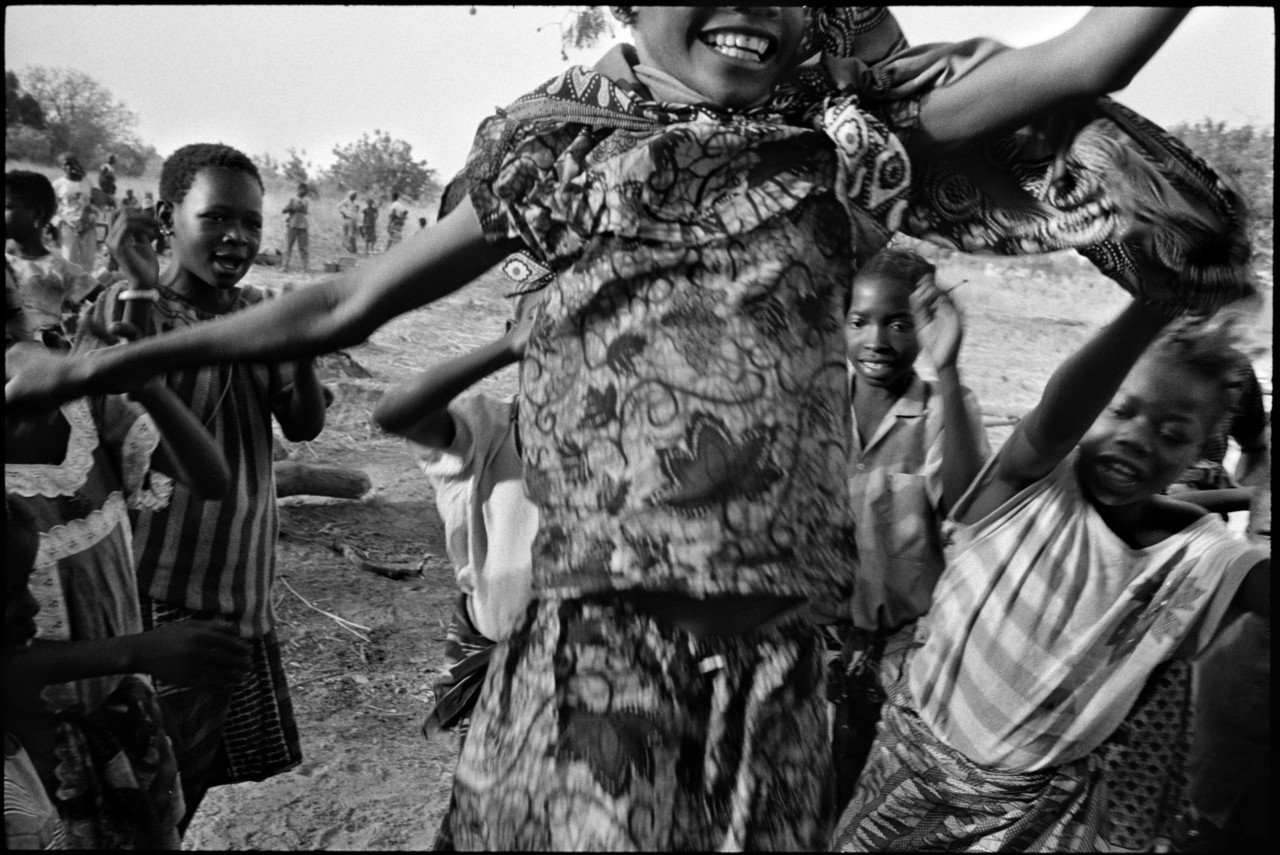

To celebrate Unesco World Dance Day, three Magnum photographers reflect on their work on the subject offering varying points of view. Guy Le Querrec, who has taken pictures across Africa since the 1970s, found that dance was often a theme that he focused upon. And though he was always an outsider, he gained his subjects’ trust and respect by shedding his inhibitions early on.

Meanwhile for Martin Parr, the subject has been an enduring fascination for decades—across cultures and continents, from novelty hen-dos to raucous weddings. Parr may be less willing to stay up into the wee hours than he used to be, but he will never grow tired of photographing the inexplicable energy that is released when people start to move.

Magnum nominee Lua Ribeira spent several years photographing Dancehall culture in Britain, but was ultimately drawn to what it symbolised outside of the physical act itself.

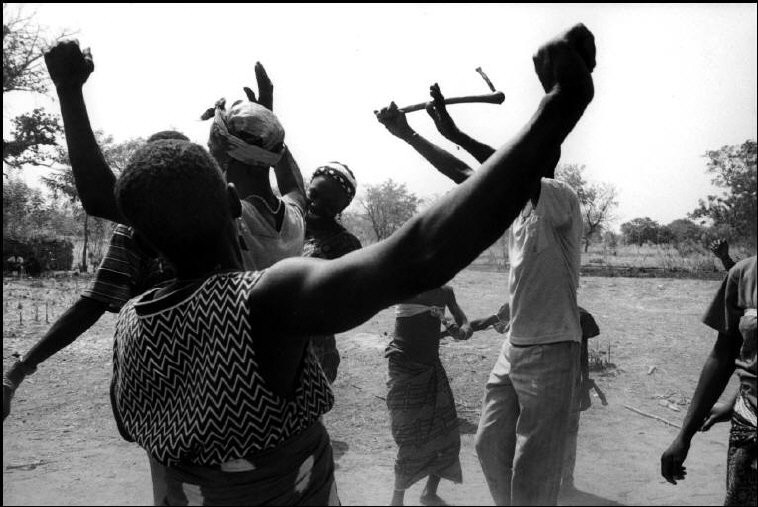

GUY LE QUERREC

What characterises my practice is gesture; what it means to greet someone, to say goodbye, to grab a bottle from the table – gesture. And obviously in dance the gesture is pushed to its very limits. Choreography is the construction of gesture. With quick moments, the most important aspect of photography is anticipation, whether in dance or not. In my images, in a way, dance is the [choreographic] score from which my eye improvises. It improvises because even if we have already seen the performance and we think know how it will unfold, it is always an improvisation.

Especially the dances I shot in African countries – they were often very precise, but also very unpredictable – you never know what gesture will express itself next. So the most important thing is to be very attentive when observing, to anticipate and to precede the next gesture that will take place in order to shoot at precisely the right moment.

"At a certain point, dance was like a passport because there were places where we weren’t so welcome"

- Guy Le Querrec

I always danced myself; it was natural for me and my family to dance at parties or family reunions. We danced ordinary dances: the polka, the java, and so forth. But as I was very soon interested in jazz, jazz as music that facilitates the expression of dance itself, I became interested in its rhythms and cadences; so I always enjoyed dance through its relation to music.

As of 1970 I travelled a great deal throughout Africa, and have passed through 30 countries there. It is a continent that is very much inspired by dance from all perspectives, joyful occasions as well as sad ones—even at funerals in parts of Africa, there is dancing. So I dared, quite early on, to mingle with the dances I came across there. Not to sound pretentious, but people liked the way I danced a lot. Sometimes it prevented me from taking pictures—I would put down my camera and dance instead.

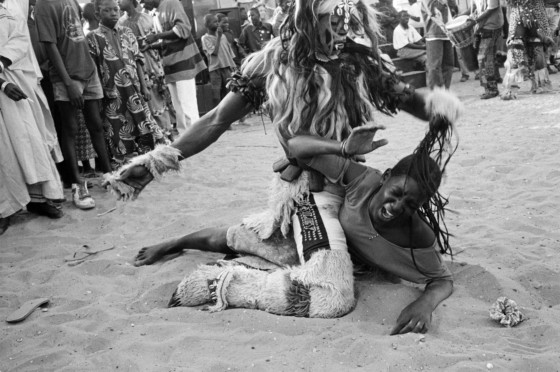

I photographed the dance of the false lion [Simb Gaïndé] in Saint Louis, Senegal. The dance is a tradition particular to Senegal and the basic concept is as follows: one performer would disguise themselves as a lion (which is of course a threatening animal that villagers feared when it would come close to the township) and the other performers would dress as panthers. It’s not expensive to watch, but the parents must buy a ticket for children to attend this performance. There is no barricade, only a naturally formed circle, but if a child happens to arrive without a ticket then the lion grabs the child and beats them—not severely, but the child is beaten nonetheless; the lion wreaks vengeance on whoever didn’t pay for a ticket to the performance.

Though the beatings are never brutal, sometimes the child would play the trickster and cry theatrically, “Don’t hurt me, it hurts!” And in fact as soon as the lion left, the child would laugh and waggle their thumb at them. Human behaviour and society reveals itself in these kinds of scenarios; the audience can choose to expose the children who don’t have tickets, or they can protect them. In many such dances there are underlying lessons about human behaviour; the choreography represents scenes from life and there is a certain moral lesson to be learnt.

Burkina Faso is where I did the longest reportage in an African country. I was there on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Magnum Photos, with the Lobi people, an ethnicity who are present in Burkina Faso and also in Ghana. During my time in Africa news seemed to travel fast, so when I would arrive in the next village, people already knew that I would be dancing. Because I was such an anomaly, the word spread quickly. And I know that at a certain point, dance was like a passport, because there were places where we weren’t so welcome.

When I saw that there might be some reticence on the part of locals, I began to dance and all the doors would open. I wouldn’t have done it only to “buy” their approval, but also because I wanted to. In the beginning I was intimidated but little by little I began to have more courage, and I noticed that they were pleased that we joined them in dancing; it was a way of showing how ordinary we were.

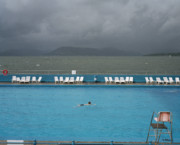

MARTIN PARR

I photograph dancing because I love this energy that is suddenly released when people have had a few drinks potentially or hear the right music; they have this urge that you can hardly describe to get up and start dancing. That energy is something really attractive and interesting and it makes me want to photograph it.

I’m always looking for the hot spot; if there’s a dance floor you’re looking for the people who are doing the most energetic dancing—really throwing themselves in. It’s really about following the energy around.

"I’ve photographed dancing all around the world, it shows that despite everything, there’s a lot we all have in common"

- Martin Parr

As with my other subjects, I have the issue with people being aware I’m photographing them because they are facing the camera. You’ve got to sit it out or persuade them not to and then the danger is they’re not looking at the camera and then you’ve got their backs. It’s a very difficult subject to photograph which is why I’m so intrigued by it and I keep coming back to it because I know, you can never have enough dance pictures.

I’ve photographed dancing all around the world, it shows that despite everything, there’s a lot we all have in common; the same energy is released. Sometimes you have specific dances like country dancing, where there’s set rules but most of the time it’s just: let yourself go !

In order to capture these fleeting moments you have the right shutter speed, the right balance…and this has become so much easier since the digital era, it’s one of the huge benefits of digital. Most of the dancing pictures I take are rubbish—I go to a dance and will think: ‘This is a great dance but the pictures are rubbish—they often don’t work, but there you go.

There are a few subjects I keep returning to: the beach, dancing, horse racing; these are all featured now in the upcoming show [Only Human at the National Portrait Gallery] and are all themes I can never grow tired of. I’ve just been in India and I’ve got a whole load of pictures from there; young Indian men are amazing dancers, the energy there is incredible.

I will never tire of photographing dancing but you often have to be out very late, which is a drag. As I’m getting old, sometimes I have to retire by 1AM instead of going for the whole night.

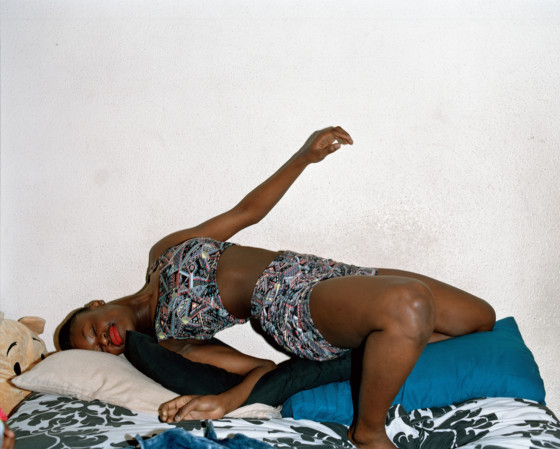

LUA RIBEIRA

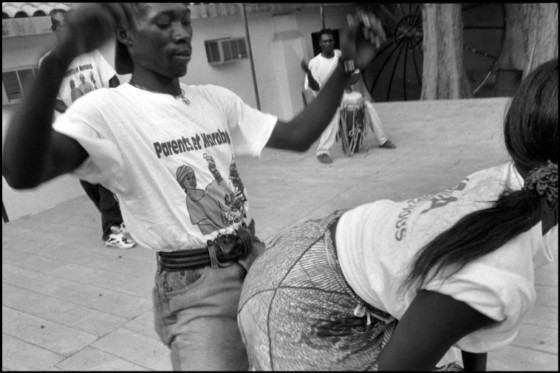

I see dancing as an art, a way of expressing ourselves through body movement. However, within the project Noises in the Blood,I needed to move somewhat away from the dance itself. Dancehall has often been photographed with a series of connotations attached (sub-culture, gangster, club-culture) which I wanted to move away from. Instead I aimed to focus in the knowledge and heritage of this culture, as well as in the mystery caused by the impossibility of fully understanding it from my own point of view.

Dancehall is currently one of the biggest cultural movements within Jamaica and its diaspora. It has expanded worldwide, not just through the music, but also the sound, dance, fashion and language… It has been influenced by many other movements and is in constant transformation, yet its roots are in Afro-Caribbean culture and history.

"I had an admiration for Jamaican culture and the strength with which something like dancehall was kept alive and protected, almost as a form of resistance

"

- Lua Ribeira

Dancehall reveals many things about a culture’s knowledge: ideas of femininity, relationships with the body and sexuality, celebration and spirituality and so on. It also reveals that Dancehall has embedded an element of transgression and protest against the social rigidity imposed by a dominating culture. This is expressed throughout the dance, the manners, and the fashion. Writers like Carolyn Cooper and Norman C. Stolzoff have written essential works exploring dancehall within those terms.

I navigated documenting a dance culture that I’m an outsider to by accepting that and acknowledging that I’m working from a very particular point of view. I am not interested in explaining dancehall culture, and I am not sure photography is capable of doing so. It is about documenting the relationship that I, someone from the north of Spain living in the UK, establishes with this culture that is taking place in the house next door. It is about that collision and mirroring process, which also allows me to question and learn about my own perspective and culture.

I come from a place where language and cultural manifestations were heavily oppressed during the fascist dictatorship in Spain, not long ago. This had a drastic effect on the conception of our own identity. While living in the UK, I had an admiration for Jamaican culture and the strength with which something like dancehall was kept alive and protected, almost as a form of resistance.