The Lure of Pleasure

Martin Parr's book, From the Pope to a Flat White: Ireland 1979-2019, brings together four decades of work made in Ireland, from his early black and white images of Papal visits and rusting Morris Minors, through to color images of a changing nation

For the first time four decades of Martin Parr‘s work made in Ireland has been brought together in a book, From the Pope to a Flat White, Ireland 1979-2019. The book charts Parr’s own changing practice alongside Ireland’s changing nature and society – chronologically running from black and white images of pilgrims and the visit of Pope John Paul through to color images of chains, startups, and gentrification.

The book’s introductory essay, by Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole, is reproduced in this long-read, alongside a small selection of images from the publication.

From the Pope to a Flat White, Ireland 1979-2019 is available from the Magnum Shop, here.

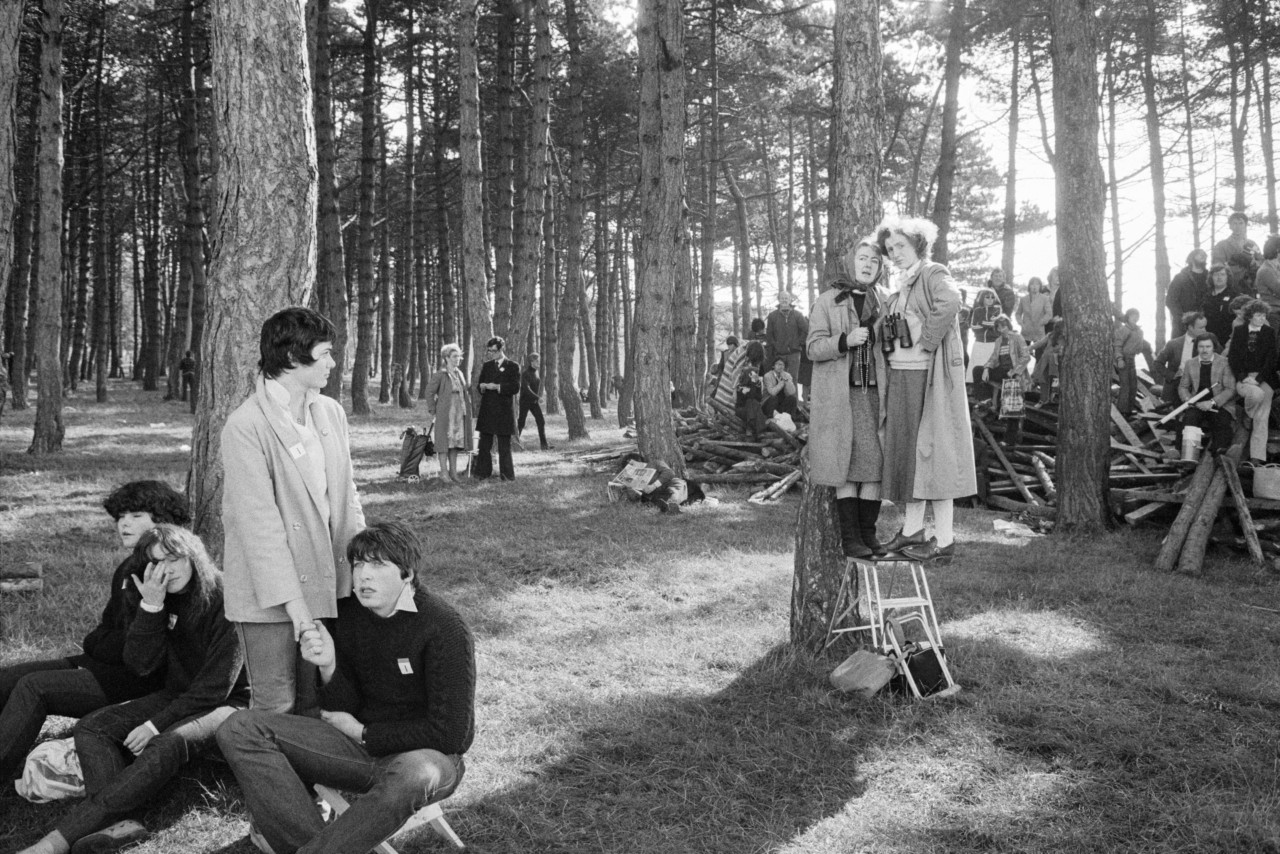

In the Catholic calendar, September 29th is the feast day of the archangels Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, who protect us against temptation, carry messages from on high and guard us on our travels. In Martin Parr’s wonderfully evocative photographs of the Phoenix Park in Dublin on that morning in September 1979, people are waiting for an angel. In a few hours, Pope John Paul II will swoop in over their heads in a big red helicopter. More than a million heads will turn to watch it arc gently downwards behind a vast stage. When the Pope emerges, there will be a phenomenon not experienced before in such a vast throng: utter silence. The crowd will hang on every word, as if hearing a message from the Divine.

But that is still to come. Parr’s photographs capture, not the event but the expectation. His habit, implicit in so many of his images, is to be there first. It allows his presence to be noticed, then taken for granted. But it also allows him, as here, to capture the moments before the moment. The low morning sun gives the gathering pilgrims long shadows, like second incorporeal selves. A group is perched among trees, as if it had just sprung up from the ground. Something big is about to unfold, but these are pictures of anticipation.

And the message they will hear is also one of anticipation. John Paul is indeed angelic: commanding, charismatic, radiating authority and spiritual power. He does not shy away from announcing his presence here as a fitting reward for centuries of Irish devotion. “One of my closest friends”, he tells the crowd, “a famous professor of history in Kraków, having learned of my intention to visit Ireland, said: ‘What a blessing that the Pope goes to Ireland. This country deserves it in a special way.’ I, too, have always thought like this.” Yet, behind this magisterial gesture – you deserve my presence – there is an anxiety about what is to come.

This apprehension was not obvious at the time. On that morning, and over the three days of his visit, this seemed a moment of pure triumph. Around two-thirds of the entire population would attend one or other of the Pope’s outdoor Masses. The tone almost everywhere – on the streets, in the media – was one of utter reverence. Catholic Ireland seemed invulnerable, impervious to change or challenge. Only in retrospect can one pick out the bass note of foreboding in John Paul’s booming addresses to the faithful.

What he is afraid of is money and modernity. The Pope does not say directly that Ireland’s faithfulness was linked to its relative poverty, that the country is much more religious than the rest of western Europe because it is less developed economically. But he strongly implies it in his warnings of what may be to come. There is oddly little joy in his sermons – the focus is firmly on the looming threats he sees on the horizon, threats, aptly enough, that are encoded in visual representations: “The very capability of mass media to bring the whole world into your homes produces a new kind of confrontation with values and trends that up until now have been alien to Irish society”, he warns the faithful in Phoenix Park. “The most sacred principles, which were the sure guides for the behaviour of individuals and society, are being hollowed-out by false pretences concerning freedom, the sacredness of life, the indissolubility of marriage, the true sense of human sexuality, the right attitude towards the material goods that progress has to offer. Many people now are tempted to self-indulgence and consumerism… Prosperity and affluence, even when they are only beginning to be available to larger strata of society, tend to make people assume that they have a right to all that prosperity can bring, and thus they can become more selfish in their demands.”

Speaking in Galway at a Mass for young people the next day, he will warn that “the lure of pleasure, to be had whenever and wherever it can be found, will be strong and it may be presented to you as part of progress towards greater autonomy and freedom from rules.” In Limerick, he will conjure up the Devil himself, plotting to ensnare Ireland in his trap of material prosperity: “Satan, the tempter, the adversary of Christ, will use all his might and all his deceptions to win Ireland for the way of the world. What a victory he would gain, what a blow he would inflict on the Body of Christ in the world, if he could seduce Irish men and women away from Christ. Now is the time of testing for Ireland.”

"Ireland, as Oscar Wilde once said of himself, has by now proved itself able to resist everything except temptation. “Self-indulgence and consumerism” were, for most of those who prayed with the Pope in those heady days, already in the ascendant"

- Fintan O'Toole

Ireland gleefully failed the test. Satan the tempter had an easier job of it than either he or the Pope might have anticipated. In Parr’s photograph from the Mosney holiday camp, taken fifteen years later, a woman lies back in the sun, shading her eyes with a paperback bodice-ripper that carries the word “Temptation” on both front and back covers. She is not ashamed of herself. Ireland, as Oscar Wilde once said of himself, has by now proved itself able to resist everything except temptation. “Self-indulgence and consumerism” were, for most of those who prayed with the Pope in those heady days, already in the ascendant.

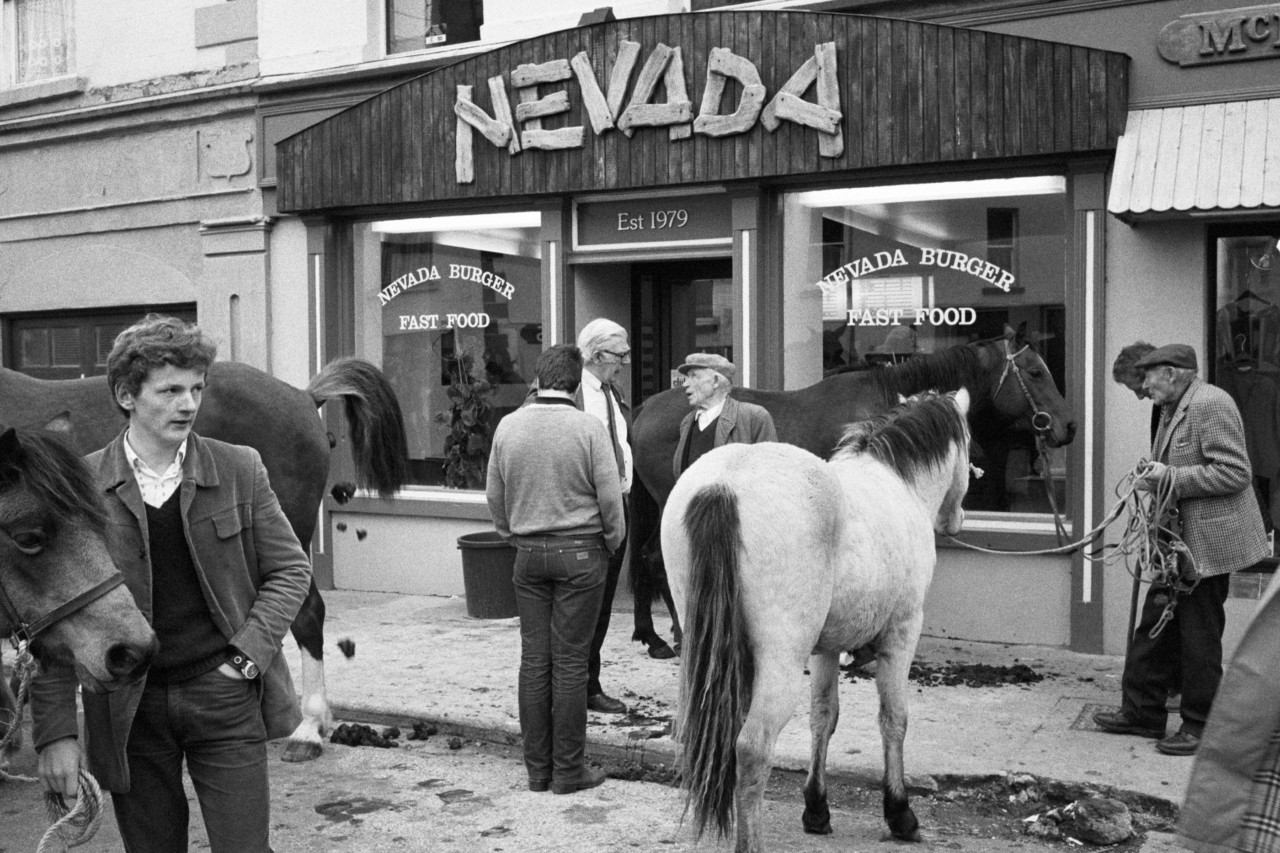

The Nevada Burger fast food joint in Westport, deliciously framed as a Wild West movie set by the horses gathered outside, boasts on its sign “Est. 1979”, the year of the Pope’s visit. It may not look glamorous now, but in 1983, when the shot was taken, it represented a token of affluence, a shard of the American way of life that Irish hearts lusted after. This is the way of the world the Pope warned against, but even rural Ireland is happy to go that way. (When Parr was taking these photographs, I was with him. I noted that inside the burger bar “one wall is boldly emblazoned with the Stars and Stripes. Underneath the sea blue Nevada state flag on the opposite wall is the motto: All for Our Country.”)

"The lure of pleasure is captured in Parr’s resonant picture of punters going into the Mayflower ballroom in the little Leitrim village of Drumshanbo in 1981... They are about to pass from the realm of the everyday into a zone of promised pleasure"

- Fintan O'Toole

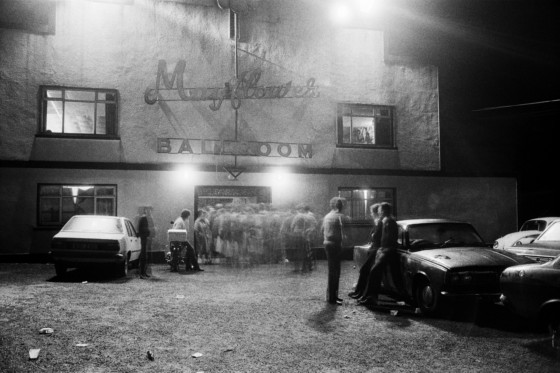

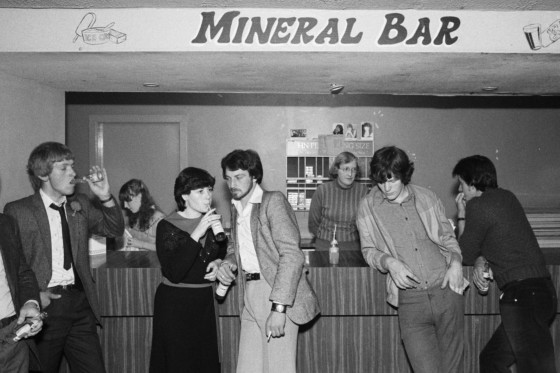

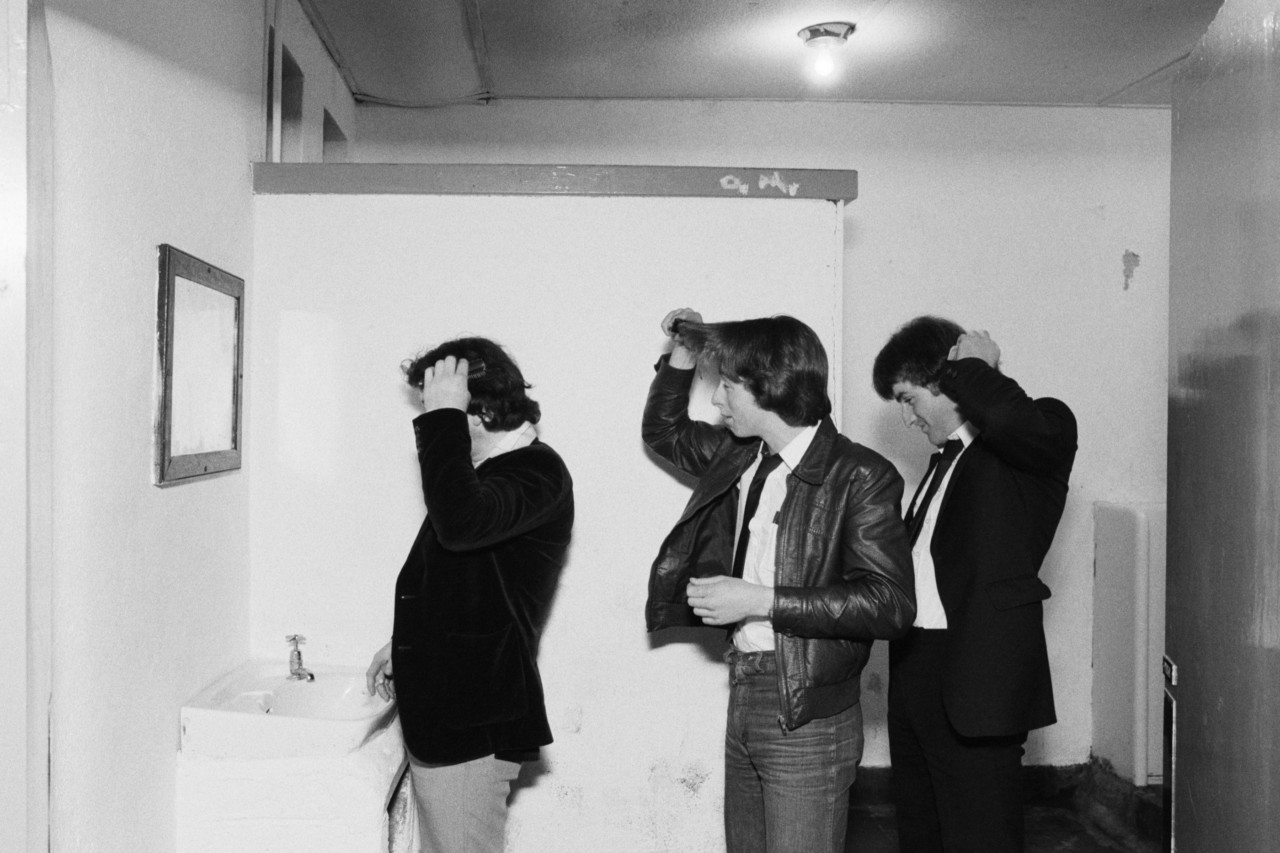

The lure of pleasure is captured in Parr’s resonant picture of punters going into the Mayflower ballroom in the little Leitrim village of Drumshanbo in 1981. The building is dated, archaic, redolent of an earlier era’s ideal of trendiness. The name, as Frank McNally wrote in 2010, is itself a relic of lost modesty: “If you were choosing a floral name for a dancing establishment of that era, ‘Passion-flower’ might have been a bit risqué. ‘Wall-flower’ would have been harsh. Whereas, what with its hints of both spring fertility rites and Marian devotion, ‘Mayflower’ was probably the ideal compromise.” But the lights, in the grain of Parr’s dreamy monochrome, have a mystical glow. The figures crowding towards the entrance shimmer as mysteriously as angels.

They are about to pass from the realm of the everyday into a zone of promised pleasure. Like the lads beautifying themselves in the toilets of the Amethyst ballroom in Roscommon in 1982, they are on the threshold of possible bliss. The reality they will encounter may be much more constrained, but the desire is unbound. It fed what seems in retrospect a remarkable industry: at its peak, there were an estimated 700 showbands touring around 1,100 ballrooms and dancehalls in Ireland. They were sure not singing hymns: even in communities where everything was watched carefully, theirs was the siren song of American and British hits, full of lust and longing.

"Like a continuity error in a historical movie, the disposable plastic cup on the bench beside the Virgin breaks the illusion that we are in a deep, static past. Likewise, the timelessness of the fierce, self-punishing climb up the holy mountain of Croagh Patrick, an ancient ritual with pre-Christian roots, is offset by the plastic bag being carried by the pilgrim"

- Fintan O'Toole

Parr lived in the West of Ireland between 1980 and 1982. It is important to note that he came for practical, ordinary reasons – his wife got a job there – and not, like so many outsiders over the previous century, in search of the exotic or the “authentic”. (Parr has always been too amused by the innate comedy of the human condition to be a romantic: the first three pictures here, from his Bad Weather project, set the tone.) Some of the early images are indeed of traditional events – horse and cattle fairs, Catholic religious gatherings, holy wells, the remarkable horse races on Glenbeigh strand. It is not just the austere black-and-white of Parr’s early style that makes them seem pre-modern. In the crowd gathered for the Corpus Christi procession in Ballaghaderreen in 1980 (pg. 20-21), what details might serve to mark a time for us now? At first glance, almost none. A closer look reveals the nuns’ wimples are definitely from after the liberalising Second Vatican Council of the mid-1960s. And the big TV aerials on the buildings in the background probably went up in the 1970s. But continuity with the past is much more obvious than these signifiers of change.

Likewise, if you showed a contemporary Irish person the picture of farmers and cattle at Puck Fair in 1980 and asked them to date it, they would probably guess at the 1940s or 1950s. The most sharp-eyed might point to the bobble hats that two of the farmers are wearing and note that they came into vogue in the 1960s. Otherwise, the scene, like many of those Parr captured at horse fairs, could almost be mediaeval. Or at the holy well in Killargue (pg. 18), there is just one detail that tells us that this is not a moment from many decades before. Like a continuity error in a historical movie, the disposable plastic cup on the bench beside the Virgin breaks the illusion that we are in a deep, static past. Likewise, the timelessness of the fierce, self-punishing climb up the holy mountain of Croagh Patrick, an ancient ritual with pre-Christian roots, is offset by the plastic bag being carried by the pilgrim.

These images are not, then, quite as fixed as them seem – Parr’s relish for anomalies almost always dispels the mirage of immutability. But they do nonetheless form a kind of baseline against which we can measure the extremity of change over the 40 years that followed. Parr’s pictures are not schematic but there is nonetheless a very rough scheme that inevitably asserts itself when you bring them together chronologically. There are images like these ones where the note of continuity with established traditions is dominant. Then there are images in which the drama and humour lie in the collision between tradition and modernity. And then there are the ones in which the old seems entirely submerged in the new. Or, as the Pope might have imagined it, there is holy Ireland, then the struggle with the satanic lure of innovation, then a wholly unholy Ireland.

The simplest measure of this transformation is economic. When Parr began to take these photographs, almost half of Irish exports still went to the UK. Of the top five categories of goods exported, number one was “meat and meat preparations”, number three was “dairy products and eggs” and number four was “live animals”. Forty years later, just 14% of Irish exports went to the UK. The top categories of goods exported were pharmaceuticals, chemicals, medical devices, machinery and computers. Whatever “globalisation” means, Ireland is what it looks like: a largely rural, heavily agricultural society becoming one of the most open and high-tech trading economies in the world. The big drivers of this change were the gradually unfolding effects of membership of the European Union, which Ireland joined in 1973, and waves of investment by foreign (especially US-based) transnational corporations.

At the time of the earliest pictures here, money had been flowing into the countryside from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy: agricultural incomes rose by 46% in 1975 alone. What people mostly wanted to do with the money was build. Many of the old farmers in these pictures were probably single men: in 1979, one in every three farmers was an unmarried and childless man. They lived in their parents’ cottages and changed them very little – without a wife to disturb them, why should they brighten the place up? For the most part, the women they might have married had emigrated long ago, to Britain or the United States. The warm sociability of the fairs and auctions is the other side of loneliness, the escape from isolation.

"It was now possible to have an American homestead in Ireland rather than pining for an Irish homestead in America. Or, as Parr records in a picture from 1986 of a new middle-class estate in Dublin, to pine for some notion of English respectability"

- Fintan O'Toole

But in these scenes of agricultural dealing, there are also younger faces. The courtship rituals Parr is observing in the dancehalls will lead to couplings and as prosperity rises in the countryside after EU membership, more of those couples will stay in their own place instead of emigrating. In 1981, 11,517 private bungalows were built in the Irish countryside – twice the number builtin 1976. In 1982 and 1983, these bungalows were the biggest single category of new housing in Ireland (40%), surpassing even urban council estates. The young couples knew what they wanted – and what they didn’t want. They did not want the old houses where lonely bachelors lived, or from which, like the abandoned cottage that Parr found with its cups and teapot and bread bin caked in dust, families had fled into exile. They wanted what was summed up in the title of the best-selling book of do-it-yourself plans: Bungalow Bliss. They wanted what one of my rural relations called, in an unironic expression of all that was desirable in life, “America at home”.

"The fabulously absurd High Chaparral, outside Westport, is a homage to the TV series of the same name, set in Arizona in the 1870s, that was immensely popular in rural Ireland in the 1970s. Perhaps it embodied for those who had it built the idea of a frontier between the new and the old. But it also marked a certain faith in the end of mass emigration to the real America"

- Fintan O'Toole

They assembled, not just houses, but images. Parr’s bungalow pictures are in a sense photographs of photographs, for what we see in them are the results of a double process of reproduction. A builder in the West of Ireland told me in 1984 how his clients decided what they wanted: “Fellas go around with cameras and take photos of houses they like around the place and they’ll ask you to put in this or that feature. You even get people bringing back photos from their holidays on the continent and maybe it’s something they’ve seen in a magazine or on television.”

The fabulously absurd High Chaparral, outside Westport, is a homage to the TV series of the same name, set in Arizona in the 1870s, that was immensely popular in rural Ireland in the 1970s. Perhaps it embodied for those who had it built the idea of a frontier between the new and the old. But it also marked a certain faith in the end of mass emigration to the real America. It was now possible to have an American homestead in Ireland rather than pining for an Irish homestead in America. Or, as Parr records in a picture from 1986 of a new middle-class estate in Dublin, to pine for some notion of English respectability: Westminster Lawns and Torquay Wood are every bit as absurd as The High Chaparral, and in their own unctuous way, even less culturally confident.

"At the time these images were being made by Parr, the Pope, had he seen them, might well have felt that he had nothing to fear from what they seemed to express. They do show radical change, but it is a particularly conservative kind of change. The young couples who were building these houses were overwhelmingly Catholic and the Church was stronger than ever"

- Fintan O'Toole

At the time these images were being made by Parr, the Pope, had he seen them, might well have felt that he had nothing to fear from what they seemed to express. They do show radical change, but it is a particularly conservative kind of change. The young couples who were building these houses were overwhelmingly Catholic and the Church was stronger than ever. One in ten boys born in Ireland in 1980 was named John Paul. In 1983, in the wake of the original John Paul’s visit, Ireland voted by two-to-one to insert an ultra-Catholic clause banning abortion from the moment of conception into its Constitution. Yet in 2018, Ireland voted by the same margin to remove the clause. Between 1974 and 2008, weekly Mass attendance fell from 91% to 43% of the population and monthly attendance at Confession fell from 47% to 9%. The turnaround was spectacular, but it was not quick.

For a long time afterwards, the Pope’s warnings that morning in 1979 might have seemed wide of the mark. The emergence of an increasingly wealthy, increasingly urbanised consumer society did not ostensibly seem to threaten the old religious order. The Church remained powerful and social legislation was still, by European standards, astonishingly conservative. In 1986, an attempt to remove a ban on divorce from the Constitution was resoundingly defeated – it succeeded in 1995, but only by a tiny margin. Yet such public tokens of the strength of the ancient regime were deceptive. Parr’s photographs from the early 1980s already capture something profoundly unsettling: the sense of abandonment. Some of his images of new bungalows showed the old house still standing behind the new one, as if mocking the past.

When they were first displayed in 1984, Parr’s sequence of images of Morris Minors abandonedin fields and yards seemed mostly funny, a brilliantly subversive take on the tradition of Irish landscape painting and photography in which the human presence is erased. They still are, but they also now have a more forlorn air – something is being forsaken. A way of life is being cast off. Time is erasing these vestiges of a more frugal past. The humour has not diminished but the poor old cars, gradually sinking back into nature, have something of the poignancy of the archaeological remains of a lost civilisation. And if they can be abandoned so ruthlessly, what else can be ditched?

"Parr’s shift from black-and-white to colour in the mid-1980s exaggerates and dramatises a shift that was of course more gradual and complex. In fact, Ireland’s transformation did not go in a straight line: the 1980s were marked by recession, high unemployment and the resumption of mass emigration"

- Fintan O'Toole

Parr’s shift from black-and-white to colour in the mid-1980s exaggerates and dramatises a shift that was of course more gradual and complex. In fact, Ireland’s transformation did not go in a straight line: the 1980s were marked by recession, high unemployment and the resumption of mass emigration. The people queuing up to buy tins of Pedigree Chum that may have fallen off the back of a lorry in Dublin’s inner city in 1986 are hardly corrupted by affluence. And the idea of escaping a troubled past was always haunted by the continuation of a long, obscene conflict in Northern Ireland, in which rigid tribal identities were enforced by violence. Parr captures that conflict in retrospect, through the self-conscious ways in which it has been turned into display, spectacle and even a tourism product. But it cast at the time a very deep shadow over any narrative of progress and modernity – at times, especially through the 1980s, it seemed that history offered glimpses of a different future only as a bitter joke.

The Troubles and the very high levels of religious practice marked Ireland out as apparently different from the rest of western Europe. But Irish people on the whole never wanted to be exceptional or exotic. We know this because for centuries they had emigrated in huge numbers to live more ordinary lives in the urban, industrial worlds of London and Boston, Glasgow and New York. It is impossible to understand Ireland without bearing in mind that two million people left the island between 1921 and 2001 (1.5 million from what is now the Republic; half a million from Northern Ireland) – a trend that recommenced with a vengeance in the 1980s: 472,000 people left Ireland between 1983 and 1993.

The apparent stability of the society, the long reign of conformism that the Pope was so enamoured of, was an illusion created by the reality that the most radical changes in peoples’ lives were happening in that great Irish shadowland, Elsewhere. That is where people went to get the kind of lives they wanted.

The transformation of Ireland in the 1990s can be seen in some ways as a repatriation of this desire. In order to maintain a “traditional” way of life at home, a very large part of the population had been forced to seek out a “modern” life abroad. It made more sense in the end to bring this modernity home. Instead of Irish labour moving towards American capital, why not do it the other way around? American companies seeking a comfortable spot in the EU increasingly picked Ireland as a stable, English-speaking base with an increasingly well-educated population.

"The idea of Ireland as a magnet for large scale inward migration was scarcely imaginable in 1979 – the forces of repulsion were vastly stronger than those of attraction. Now, over 17% of the Irish population is made up of people born somewhere else"

- Fintan O'Toole

It is almost too metaphorically apt that Pfizer chose to make all the world’s supply of Viagra in Ringaskiddy, County Cork, while most Botox is made in Westport, previously the home of Nevada Burger. The lifting effects of the wave of investment that poured into Ireland from the mid-1990s onwards have been remarkable. In 1979, the population of the Republic was 3.4 million. In 2020, it is over five million, the highest level since the 1850s. In 1979, about 1.15 million people were in paid employment; not much more than 50 years previously. In 2020, there are 2.36 million at work – more than double the number. Living standards rose from being roughly 60% of the western European average to 100%. This was not a simple trajectory. Ireland suffered the global banking crisis of 2008 in an extreme way and experienced very severe social and economic damage. But the broad transformation is as clear as it is remarkable.

The most dramatic aspect of this change is probably inward migration. When John Paul arrived in Ireland in 1979, there were very few of his compatriots on the island. Now there are 125,000 living in Ireland and Polish has surpassed Irish as the second most commonly spoken in Irish homes. The idea of Ireland as a magnet for large scale inward migration was scarcely imaginable in 1979 – the forces of repulsion were vastly stronger than those of attraction. Now, over 17% of the Irish population is made up of people born somewhere else. The holiday camp at Mosney, scene of some of Parr’s photographs from 1994, closed six years later (it was no longer Ireland’s idea of fun) and became a camp for asylum seekers. In his sly image of the front of a betting shop in Dublin in 2016, all the arrows point towards migration: the Tian Du hair salon and the company offering translation services.

"Over time, this new brand may be seen to be just as problematic as the one it has replaced. As the golden child of hyper-globalisation Ireland may be heir to many of its contradictions. It may be that some of what was forsaken – some enduring way of belonging – will come to be regretted and sought for again"

- Fintan O'Toole

The stereotypes of Irishness that Parr plays with so delightfully in his images from the period of his Common Sense project in 1997 – the red hair and the priest’s dog collar – never really went away, of course. Because of tourism and the notion of Ireland as a global brand, clichés have a long radioactive half-life. Parr’s own work in this period moved ever further from any notion of the innocently “candid” shot to explore the increasingly self-conscious ways in which, in the age of the camera phone and social media, people are staging their own public appearances. Irishness has always been to some extent a performance, whether of piety or of revelry, of sophistication or of simplicity – even, in Parr’s images of Troubles tourism, of tragedy. It continues to be so even in a globalised world of flat whites and yoga sessions.

But these continuities do not detract from the sense of abandonment. The word has two essentially opposite meanings. To be abandoned is to be forsaken. But there is also wild abandon, the joy of losing the run of oneself. Both meanings hover over this visual record of the last 40 years. Ireland did – perhaps rather ruthlessly – abandon one sense of itself in these decades, trading in a singular status as a beacon of Catholic virtue and rural simplicity for a whole new selfimage of openness, tolerance and diversity. The reversal was made official in 2015 when Ireland became the first country in the world to introduce equal marriage rights for same sex couples by popular vote. The pleasure of it oozes from Parr’s photograph of the newlyweds.

Over time, this new brand may be seen to be just as problematic as the one it has replaced. As the golden child of hyper-globalisation Ireland may be heir to many of its contradictions. It may be that some of what was forsaken – some enduring way of belonging – will come to be regretted and sought for again. Yet the wild abandon of escaping from some very dark history is for now enough to be going on with.