From Civil Strife to Global Superpower: 80 Years of Magnum in China

Colin Pantall, one of the Editors of Magnum China, a new book exploring the depth and variety of Magnum photographers’ work in the country, here explains the challenges and approaches to cohesively representing an archive spanning 80 years

Magnum photographers’ earliest work in China dates from the 30s and 40s, when founders of the agency, Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, visited the country on assignments. These journeys were the first of many for Magnum’s members who would over the coming years develop a longstanding cultural engagement with China – notable early works including those by Marc Riboud, Eve Arnold and René Burri.

Magnum China, published by Thames & Hudson, explores the various approaches, practices, and projects of Magnum’s photographers in the country. The agency’s members have been witnesses to defining events, ructions, and flourishings in the nation – from the civil war, to the Cultural Revolution, through to China’s more recent transformation into an economic powerhouse and global power.

The book finishes with works by Christopher Anderson, from Magnum’s 2017 Live Lab in Shenzhen, which featured in his recent publication Approximate Joy, and includes recent bodies of work from Martin Parr, Patrick Zachmann, Carolyn Drake and Jim Goldberg, among others, reflecting the thorough and multi-layered photographic account of the nation that remains ongoing. To celebrate the launch of Magnum China a new specially curated collection of fine prints is now available on the Magnum Shop, here.

Here, Pantall reflects on some of the challenges, approaches, and rewards of delving into and presenting an archive so large, representing a country so complex.

Writing and editing Magnum China, alongside my co-writer and editor Zheng Ziyu, was a mammoth undertaking. In addition to working with the extensive archive itself, we interviewed photographers, and reviewed ephemera, and additional visual materials spanning the 1930s to 2018. This period was photographed by Magnum photographers in a diversity of styles, with commissions ranging from international magazines to galleries and self-funded projects. Integrating all this material into a coherent body of work posed a considerably dilemma to Ziyu and myself.

The book opens with Robert Capa’s images from 1938 and ends with Jim Goldberg’s 2017 portfolio. It is a time scale in which China went through war, revolution, famine and political upheaval before becoming the economic and political superpower it is today. It’s also a period in which a range of photographic perspectives can be seen.

In the introduction to the book, Zheng and I talk about how these perspectives affected the photographs that appear in the book. We talk about how images reflect identity, the part performance plays in photography, the danger of cliché, the ways in which images were made and funded by Magnum photographers, and the images that dig deep into our idea of what China was, is, or could be.

For Zheng, a key image is Robert Capa’s 1938 image of a young Chinese soldier. ‘He has a child’s face, but it’s resolute, shot in close-up from a low angle,’ says Zheng. ‘This image was published on the cover of Life magazine and is, as far as I am aware, the very first time that a Chinese person has been shown by a western photographer on the cover of a high-selling influential magazine with a strongly defined character that goes beyond the usual stereotype. The typical image of the time, taken by tourists, missionaries, diplomats and scholars built an image of the Chinese as a people wallowing in ignorance and dejection. There is a sort of historical truth to this, but at the same time that idea also has orientalist and even racist elements.’

That idea, of China being the sick man of Asia, is embedded in photographic history. Go back to 1860 and you can see Felix Beato’s photographs of Chinese victims of the Second Opium War, a war which resulted in Britain forcing China to become a legal marketplace for British opium dealing.

Images like Capa’s represented a recovery from this portrayal. It’s an image where the individual represents the idea of China standing up to foreign meddling in its affairs. A similar but different idea of the individual rising above the ideological is apparent in one of my key images, Marc Riboud’s photograph of a women in Beijing.

‘I have always loved the photographs of Marc Riboud,’ I write in the book, ‘and one of the pictures that exemplifies this conflict between the ideological and the individual is his picture of the lady in Beijing wearing a fur-collared cape, a cigarette clasped between her fingers. The year is 1957 and she stands in stark contrast to everybody else on the street. This is dress as protest. This is an assertion of her individuality, of her class maybe, because it’s a picture that screams bourgeoisie.’

"I always wonder what happened to this woman in those years. What was her fate?"

- Colin Pantall

‘Look behind her and everybody else appears to be in more conventional dress; Mao caps and padded jackets. It’s almost as though this woman is clinging to some past identity through the clothes she wears, is setting herself apart from both the people and the politics around her. Nineteen fifty-seven was a tumultuous year in post PRC history, with the years to follow even more tumultuous. I always wonder what happened to this woman in those years. What was her fate? I also wonder at how this picture captures so many of the themes that are apparent throughout this overview of Magnum’s photography in China; the ideological power of dress, the way in which the individual shines through, and the way in which something extraordinary has been plucked out of the everyday flow of things.’

The period that followed, known as The Great Leap Forward, was characterized by an absence of images. In Mao’s Great Famine, Frank Dikotter estimates 45 million people died in the Great Leap Forward (including 2.5 million tortured of beaten to death, and 3 million from suicide), yet there is not one single photograph of those deaths readily available. That lack of representation is reflected in Magnum China where not one image of violence or death – from Tibet, Xinjiang, or Tiananmen– is included, an omission which is partly to do a lack of access in times of conflict and political crisis.

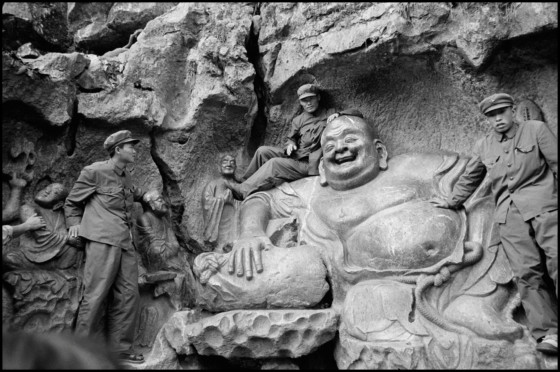

The portrayal of the Cultural Revolution was characterised by images of political theatre, of mass parades, marches and ideological book and banner waving. These images created a perception of China as a mass of unthinking, de-individualised conformity. This portrayal is evident in the hostile face that stares back at Rene Burri, it’s there in Marc Riboud’s pictures of Tiananmen rallies and it’s there in Bruno Barbey’s survey of the formalities of the opening of China to foreign diplomacy and business.

The death of Mao, and the subsequent relaxing of the ideological drawstrings, resulted in a new portrayal of China, one where the individual again could rise above the ideological and this is where Zheng chooses another key image.

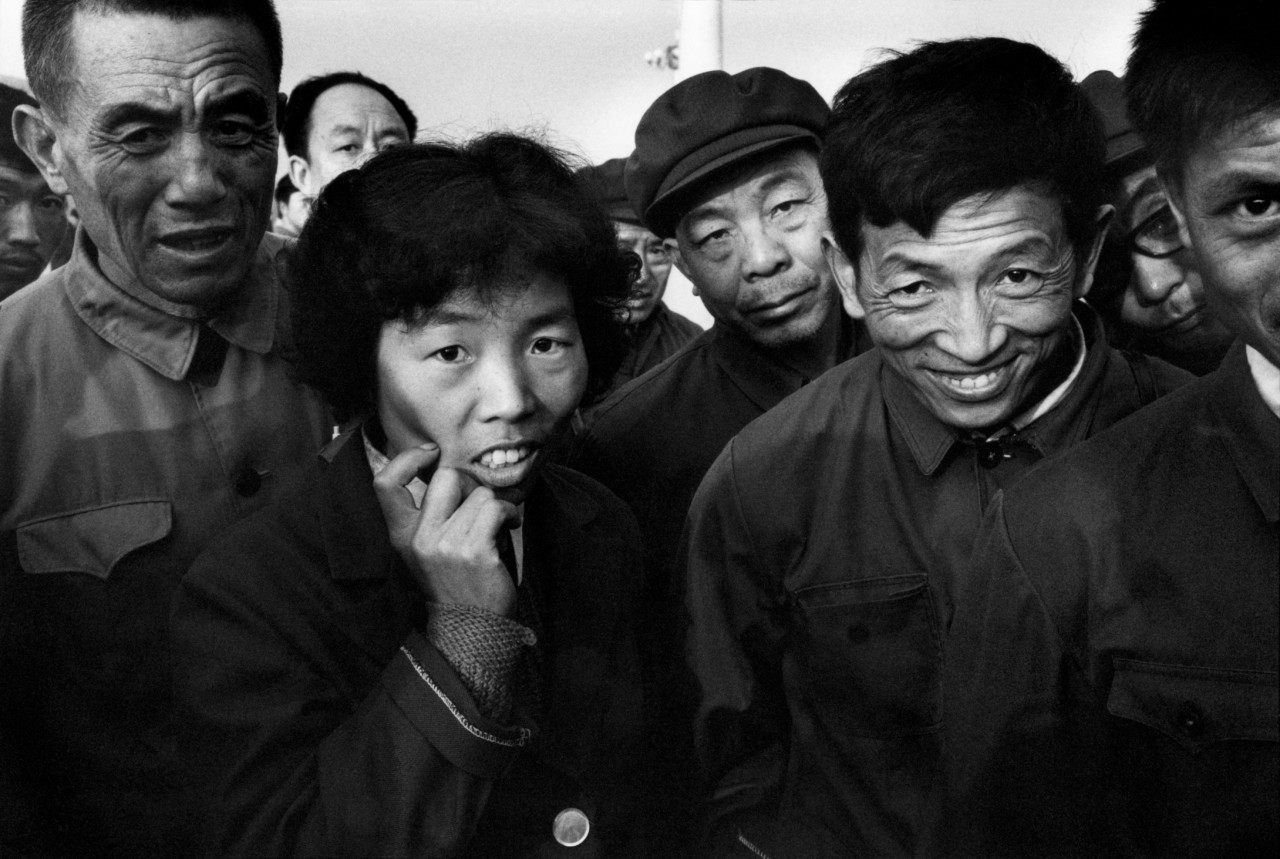

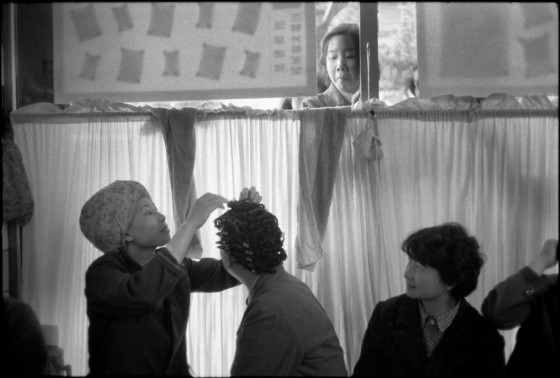

‘The other photo I would include is Patrick Zachmannn’s ‘Looking at the long-nose’ taken in 1982. Six years after Mao’s death, China was at a new turning point in its relationship with the west. Most photos recorded how western photographers saw the changing country, but this picture captured how the Chinese saw westerners, the so-called ‘long-noses’. In what looks like a simple street encounter, this photo freezes a typical street scene with a wealth of detail. There are different faces with complex emotions and gazes staring at the ‘long-nose’, making eye-contact not only between the objects and the photographer, but also between the objects and the reader.’

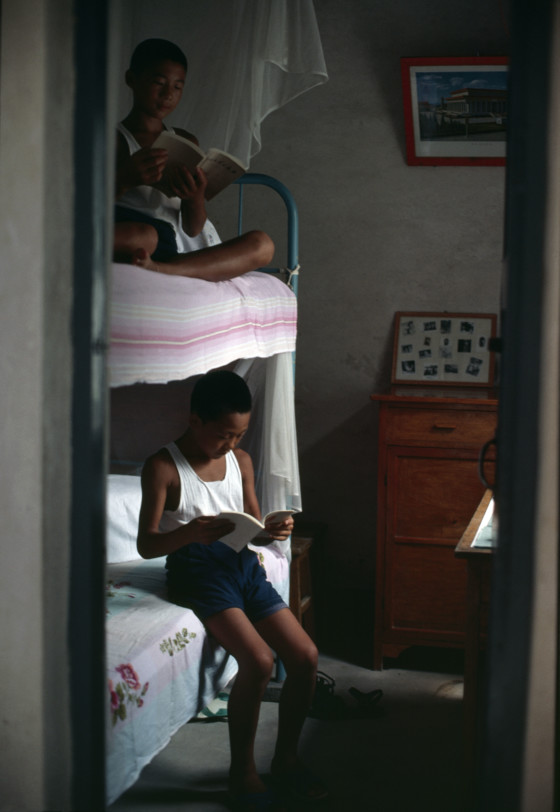

That idea of a post-Mao opening up of China is reprised in the portfolios of Inge Morath and Eve Arnold. Morath shows the cultural side of China, while Arnold’s formally posed portraits shows the diversity of its people and presents quiet, domestic moments that are intimate, universal and empathetic.

It’s an example of how different periods in Chinese history are reflected by different photographic tropes. It begs the question of whether this representation of China is the result of pre-conceived ideas of what should be photographed, a performance by the people being photographed, or a misreading on the part of the viewer.

‘There is no such thing as an innocent eye’, says Zheng. ‘Photographing a different civilization or ideology inevitably involves preconceptions and misreadings, misreadings that can unfortunately be considered to be historically accurate in nature (when they are not) and so become part of an intercultural communication that is based on flawed visual evidence.’

Photography renders only a partial view. So the photography of the Cultural Revolution shows us political performances which were put on as explicit expressions of political power (and were there to be photographed as such), but not what lies beyond.

"If you want to avoid clichés you have to abandon familiar themes, symbols and stories, and you need to be able to reflect on what you are doing"

- Zheng Ziyu

‘If you want to avoid clichés you have to abandon familiar themes, symbols and stories, and you need to be able to reflect on what you are doing,’ says Zheng. ‘It’s difficult and this may sometimes make us feel sceptical about how photography can represent a country, and how people can understand a country through photos.’

‘I define the years before Mao’s death as the era of photo scarcity, when photos of China were scarce because of China’s political isolation. Domestic photographers were all working for propaganda and photography was a tool of lies. The Magnum photographers who came to China during this era filled the void with a more humanist form of photography although there were strict restrictions too.’

"...this kind of photography saved the details and textures of a time in history and taught the Chinese how to see and how to memorialize our own history"

- Zheng Ziyu

‘Of course there were generalities and clichés inevitably. For example, look through the Magnum archive and you can find similar photos of cormorant fishing on the Li River at Guilin, or people doing tai chi in the park. But as a Chinese national and as a photo editor, I am usually attracted by details in their photos which I would never see in domestic Chinese photo stories or propaganda books. That’s my expectation for this era. I wrote in an article on Marc Riboud that this kind of photography saved the details and textures of a time in history and taught the Chinese how to see and how to memorialize our own history, after our eyes had been disciplined by propaganda for decades.’

There has also been a shift in the way Magnum photographers have worked in China and this has had an effect on the work they have made. The market has shifted from magazine commissions to more fluid cultural or gallery commissions or even self-funded work.

‘These new ways of working have really freed up different ways of seeing China,’ I write. ‘In the 1940s for example, there was a form of generalised expectation of what China looked like… After Mao died you got new generalities kicking in; the hunger for culture long denied, the advent of consumption, the rise of the new rich, and the despair of the migrant worker. And then you can add to that the political otherness of China, the exoticism of the minority peoples and the mix becomes even more generalised.’

‘The problem for any photographer is how to overcome these clichés. In the 1950s and 1960s they did so through classic humanist photographs that elevate the individual above the background noise of the war, the politics, and the criticisms. The instances we gave …of the woman in the fur-collared coat or Patrick Zachmann’s street photograph are both examples of this.’

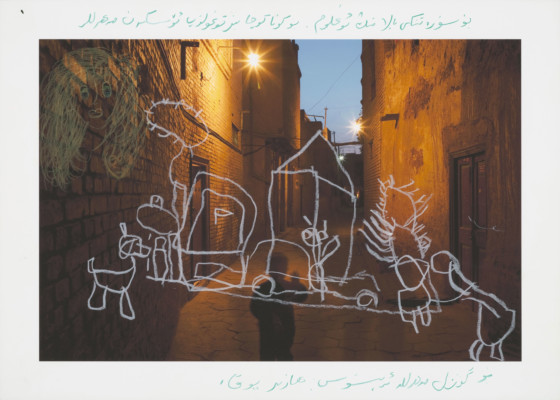

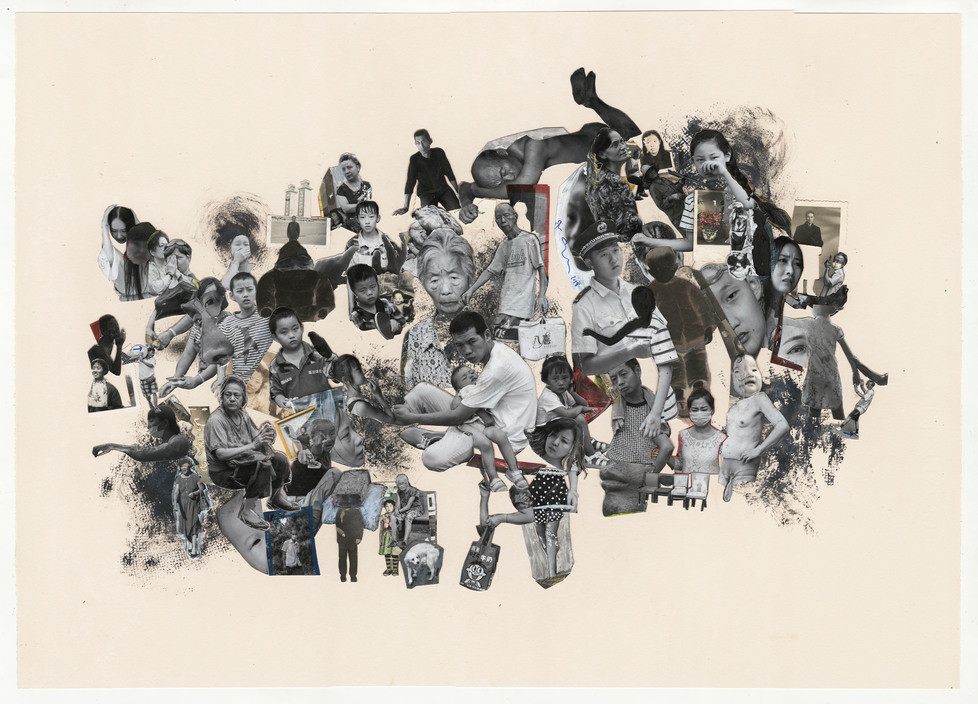

‘More recently, in the last 10 years or so, the Magnum vision has become more individualistic and diverse. With 20 years of relative stability, we know what China looks like. Now people are using sound, film, collaboration, colour, or collage to make meaningful stories that go beyond showing simply what somewhere looks like.’

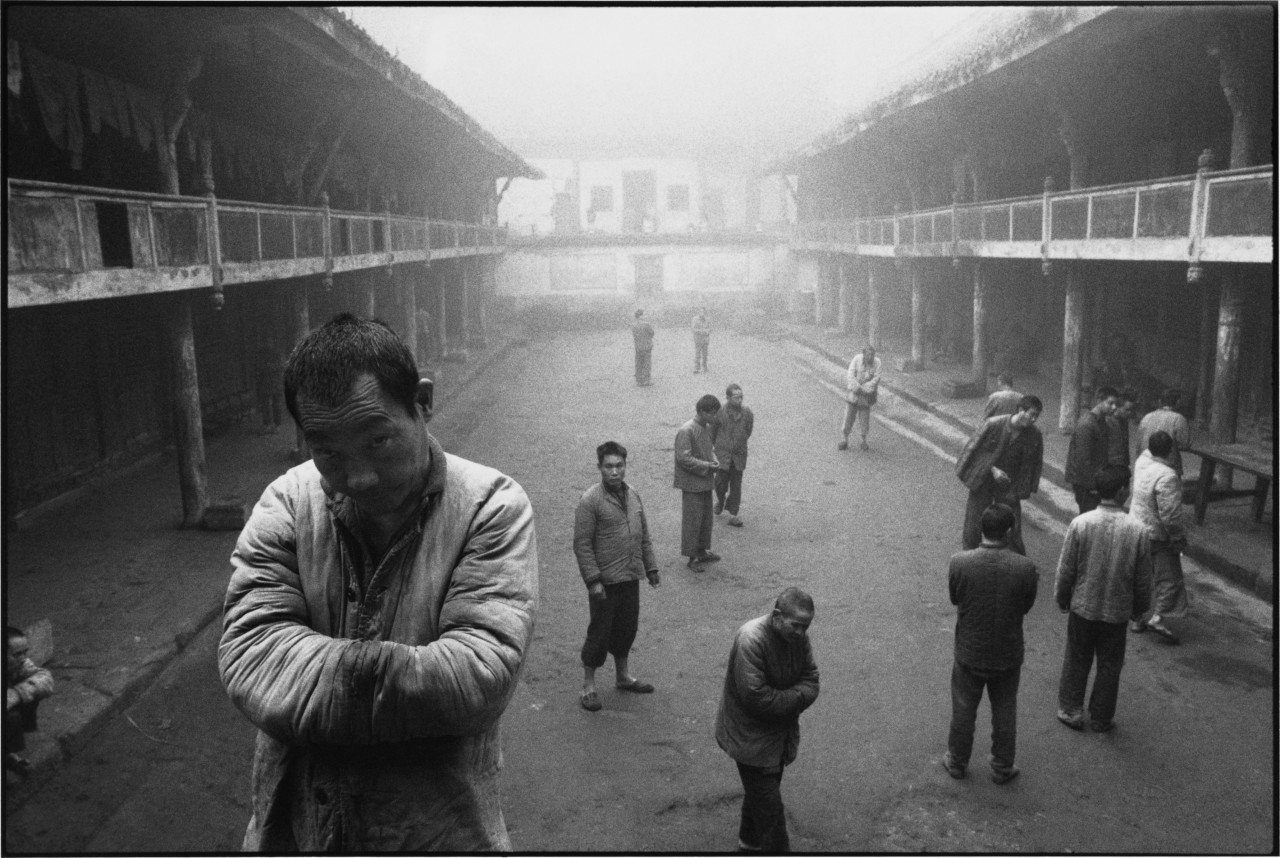

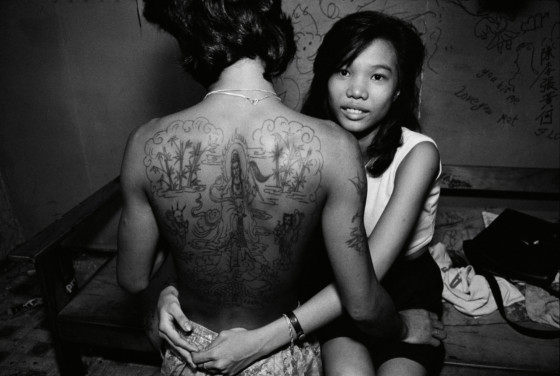

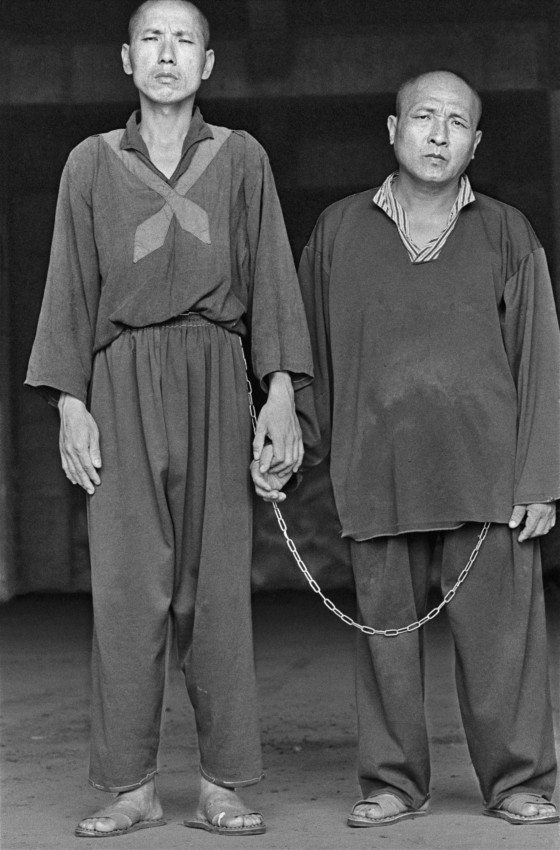

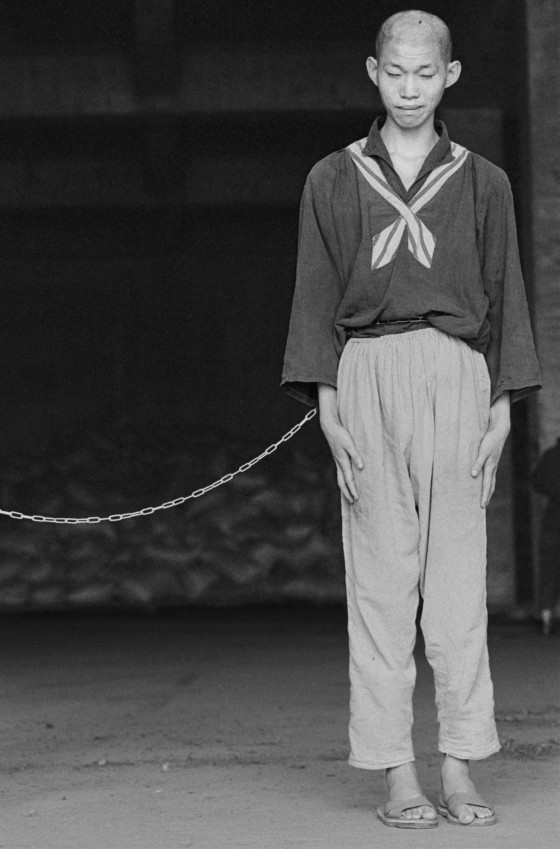

At the same time, the simple directness of photography can still tell a story that will stun you into silence. The Chain by Chien-Chi Chang is an example of this power. Chien-Chi waited 9 years to photograph for 2 hours in an asylum where inmates are chained together. It’s work that needs little elaboration.

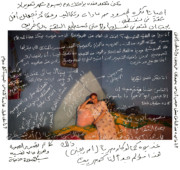

Look at his other portfolio, Escape from North Korea, a project of necessarily hidden faces and concealed identities, and you see a project where film, text messages, and multi-media all succeed in telling a story that is enveloped in paranoia and fear. It’s an example of the more open and pragmatic approach to photography that has taken hold. It’s not just about the photography anymore, but about how you make the story, how you tell the story, how you show the story.

This inventiveness and flexibility of approach is something that Zheng also picks up on in his final additions to our conversation. ‘I more appreciate photographers who emphasize their personal style, like Martin Parr and Carolyn Drake, whose photos have distinct characteristics. It is not a matter of visual evolution for me, it is just the best choice in a different context and a different era.’