Mexico City’s Santa Muerte Death Cult

As part of his personal project in and around Mexico City, Jérôme Sessini explores a ritual that personifies death in the Tepito neighborhood, which takes place every first Saturday of the month.

In June 2024, as part of his ongoing personal project to document Mexico City and its environs, Magnum photographer Jérôme Sessini documented the cult of Santa Muerte, also known as la niña blanca, a folk divinity who impersonates death and is increasingly popular among Mexico’s most vulnerable populations.

Sessini has been documenting the country for over 20 years, which he now considers to be his second home. “As a photographer, my role is to observe and document social, political, and religious movements and developments,” he explains. His work initially started by observing Mexican society through boxing culture. Mexico, alongside the USA, is the most important country in the world for boxing, home to over 180 world champions.

Over time, the French photographer shifted his attention to the violence associated with drug cartels and religious beliefs. In 2012, the photographer published The Wrong Side: Living on the Mexican Border, a three-year photographic study of the unprecedented violence in Mexico between 2008 and 2011. “What defines a war?” he asks in the book’s afterword. “Why do certain conflicts attract more attention? Certain deaths sway public opinion, others don’t… The 60,000 dead, in less than five years, will nevertheless leave a definitive mark on Mexico.”

In 2018, Sessini started to focus on Mexico City, creating a portrait of the city through its architectural features, its social phenomena, and other pertinent elements. This summer, he traveled back to the capital and decided to focus on a new chapter in the Tepito neighborhood: the ritual of Santa Muerte.

Celebrating the dead has been part of Mexico’s religious tradition since the 1500s, with roots tracing back to the Aztec ancestors. Until now, the country has celebrated the Day of the Dead in November, with processions that last for up to a week. Over the past two decades, however, a new phenomenon appeared and has since steadily grown in popularity in Tepito, one of Mexico’s most historic and central districts, and known to be one of the most violent areas of the country.

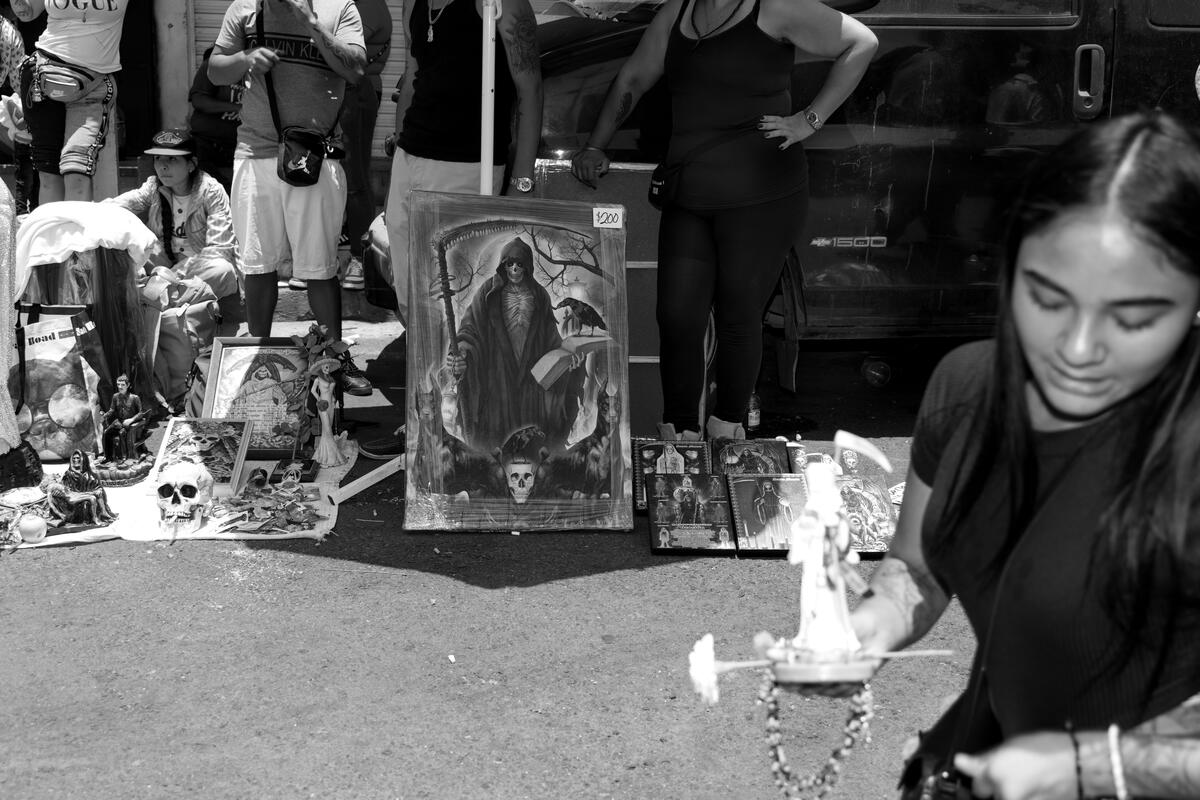

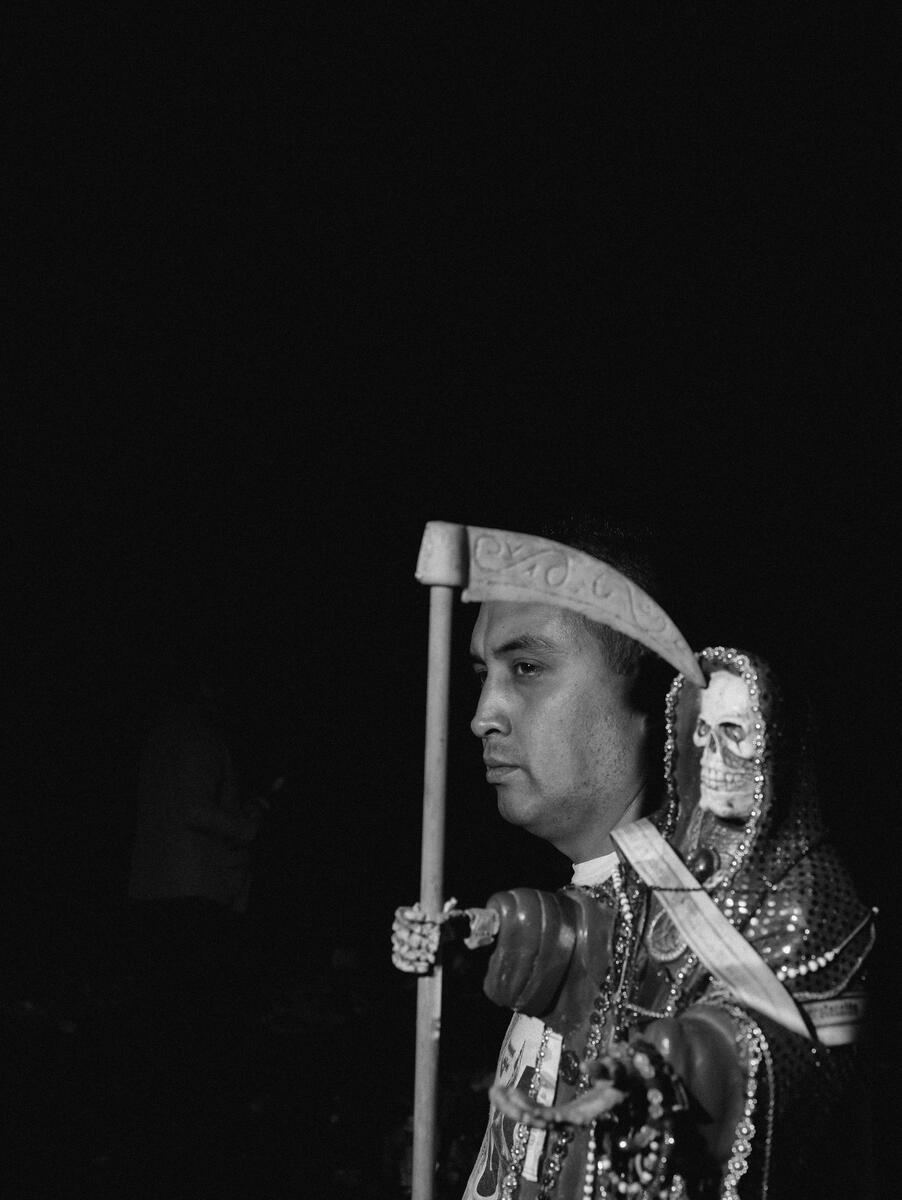

In lieu of traditional prayer for the dead, the population of Tepito has created a unique representation of the Deity of Death, a skeleton typically clothed in a robe and imbued with extraordinary powers to heal and protect the faithful. On the first Saturday of every month, the city’s largest market, where illicit drug production and counterfeit goods are readily available, becomes the epicenter of a celebration of death known as “Santa Muerte Day.”

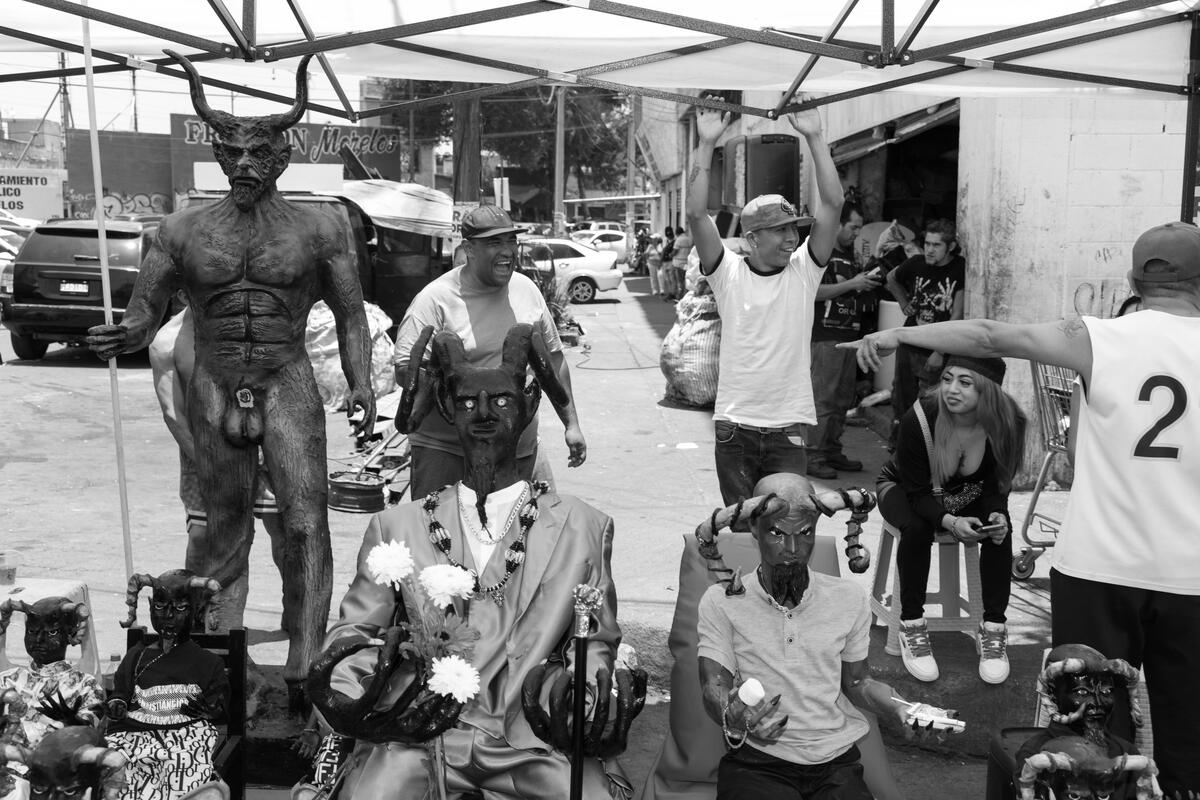

“Tepito has always had a bad reputation,” explains Sessini. “People from other areas call it “el Barrio Bravo” (the fierce neighborhood). Like in many other cities, this is part reality and part exaggeration and popular fantasy, yet Tepito is an important hub for drugs and all sorts of illegal traffic, which mechanically leads to violence and crime.”

“This is the apparition of a new saint to whom the people dedicate themselves body and soul,” he continues. “It is a very visual phenomenon that lends itself well to photography.”

Tepito is known as one of the most violent districts in Mexico City. While he was attending the procession, Sessini noted that the cult members were welcoming to all, regardless of social status. Many individuals from marginalized groups, including drug users, delinquents, ex-prisoners and, increasingly, the LGBTQ+ population, which usually faces discrimination in the neighborhood, but during the procession find a sense of belonging and recognition there.

“As a photographer I felt most welcome,” Sessini explains. “That’s absolutely not the case outside of the procession where I usually work accompanied by a local resident and touching base with the people I want to meet before entering Tepito.”

Sessini first identified the ritual in Ciudad Juárez in 2011. “It was obscured in a dimly lit room with women gathered around a lot of skeletons and effigies,” he explains. “There was a separate room where they were seeing individuals,” he adds. Since that time, the photographer has been attempting to gain a deeper understanding of the religious phenomenon and its roots through documentation.

“There has been an intensification of the phenomenon over the past decade,” says Sessini, noting the increased visibility of rituals associated with Santa Muerte on Santa Muerte Day in 2018.

In 2024, the number of participants appeared to be even greater. Most recently, Sessini has observed the appearance of a statue representing the devil. “People from other neighborhoods view them with different feelings: fear and contempt for some, but also fascination for a certain youth, who come to feel the thrill of the neighborhoods with bad reputations, without taking too many risks.”

One of the most common rituals surrounding the deity is the Santa Muerte Rosary, which consists of a procession on Alfareía Street in Tepito. During this procession, the devotees are on their knees until they reach the altar, a consecrated place with objects that commemorate the deity being prayed to.

A variety of gifts are offered, including cannabis smoke, alcohol, and flowers. “They are a means of expressing gratitude and requesting protection,” says Sessini.

The Wrong Side: Drug-Related Violence in Mexico