Only Their Names Die: A Portrait of El Salvador

Reflecting on Moises Saman's work made in the country, alongside five poems by Roque Dalton

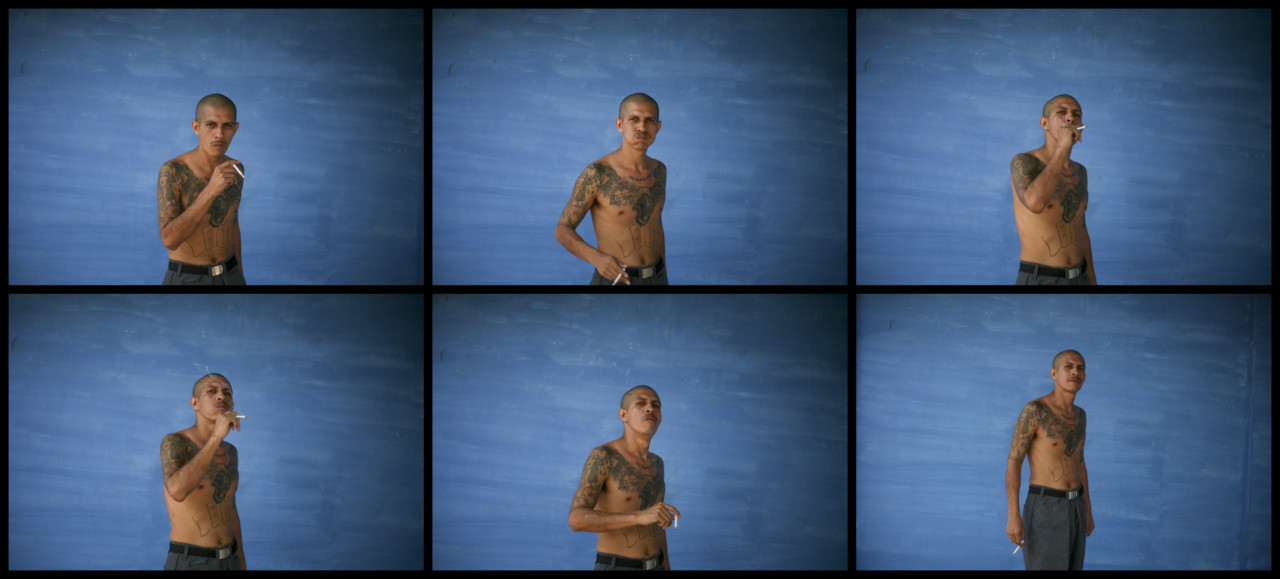

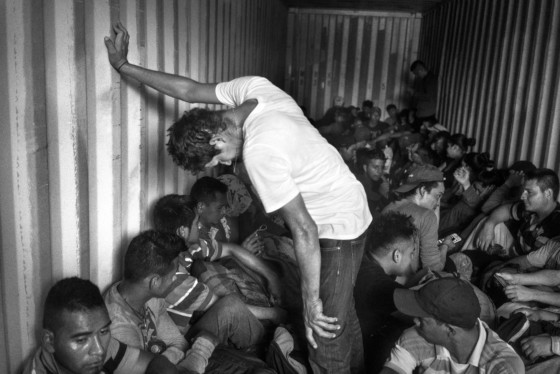

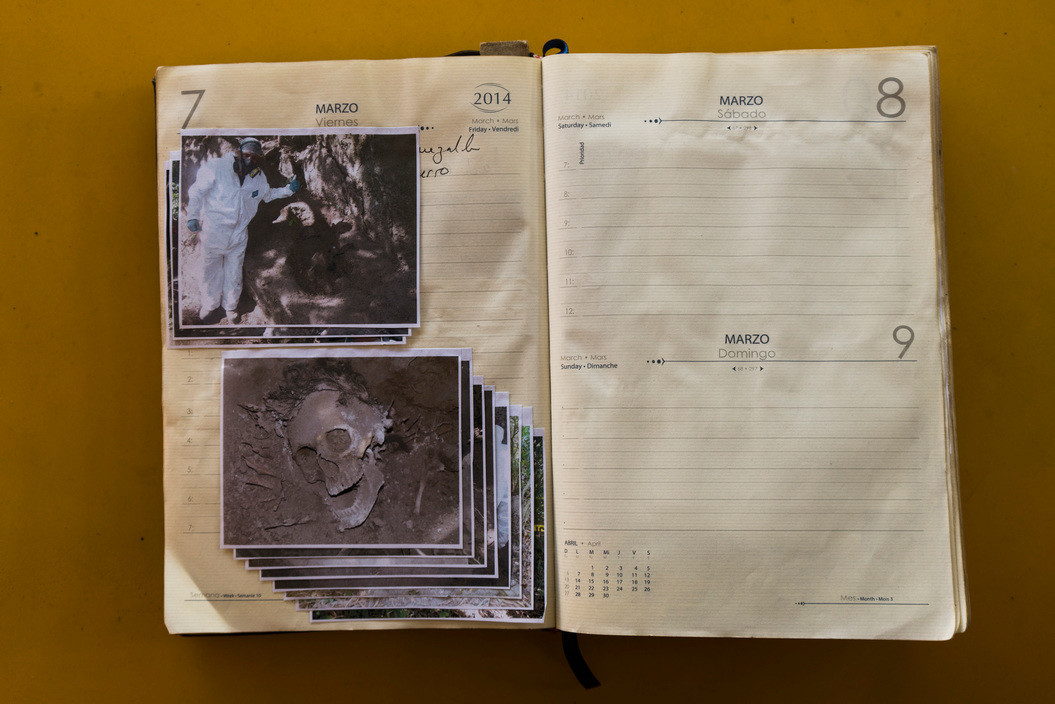

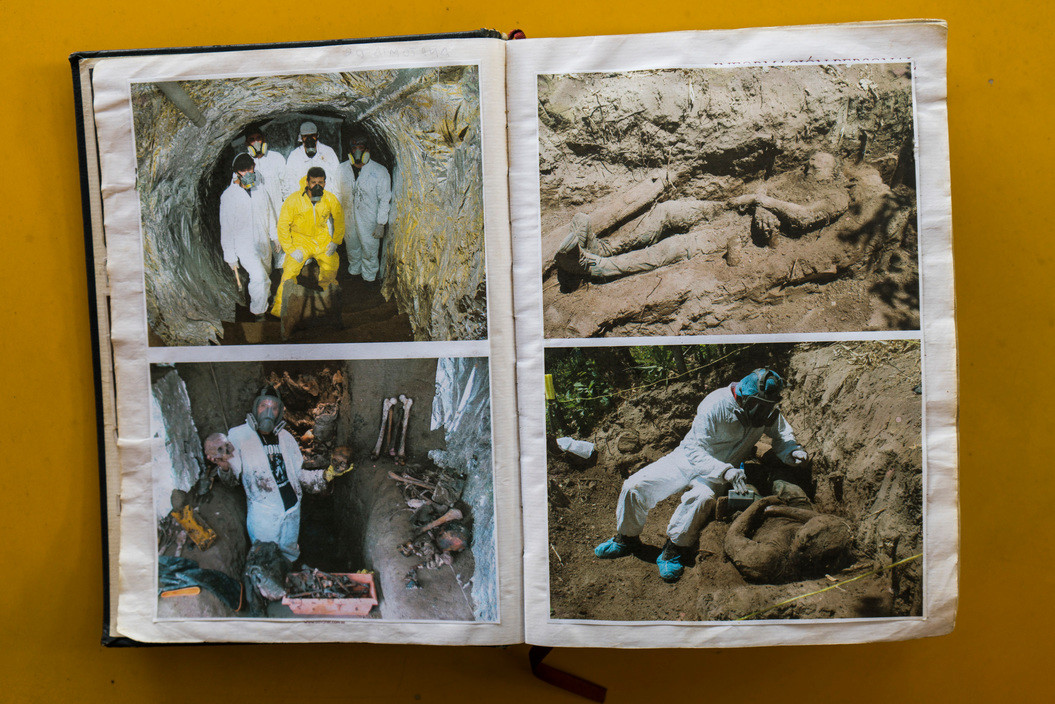

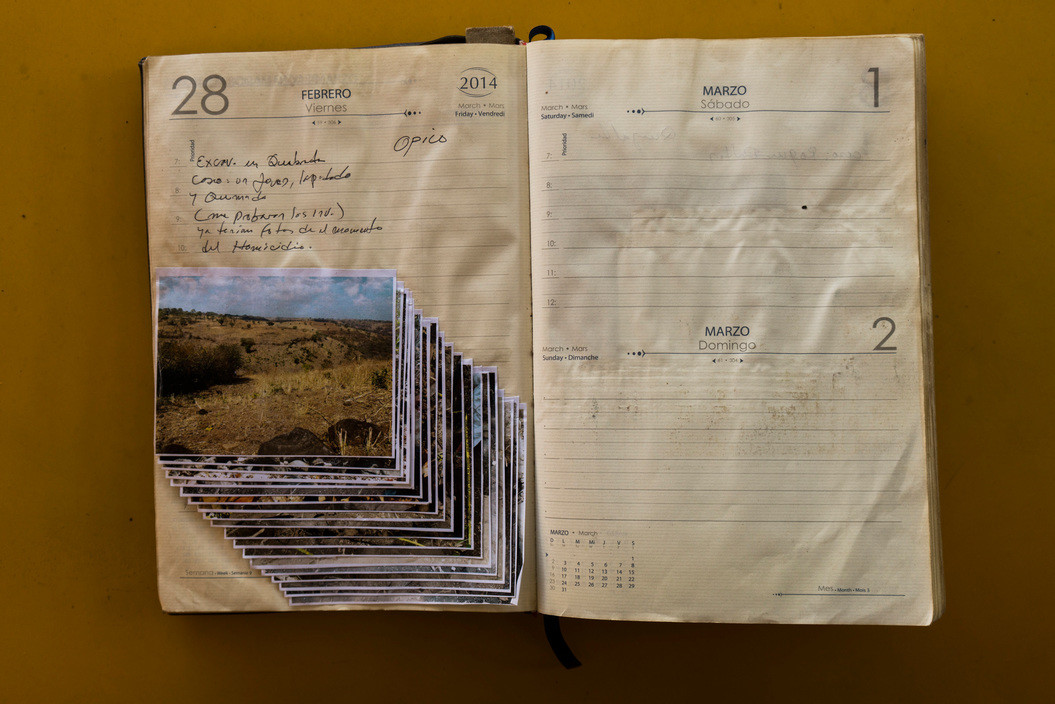

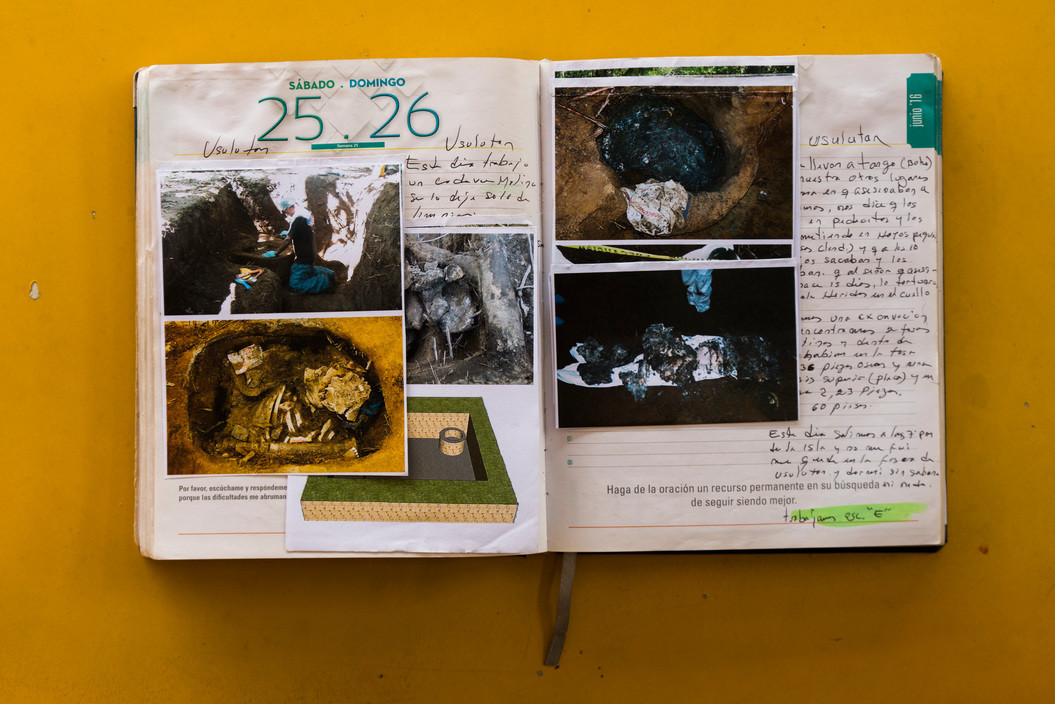

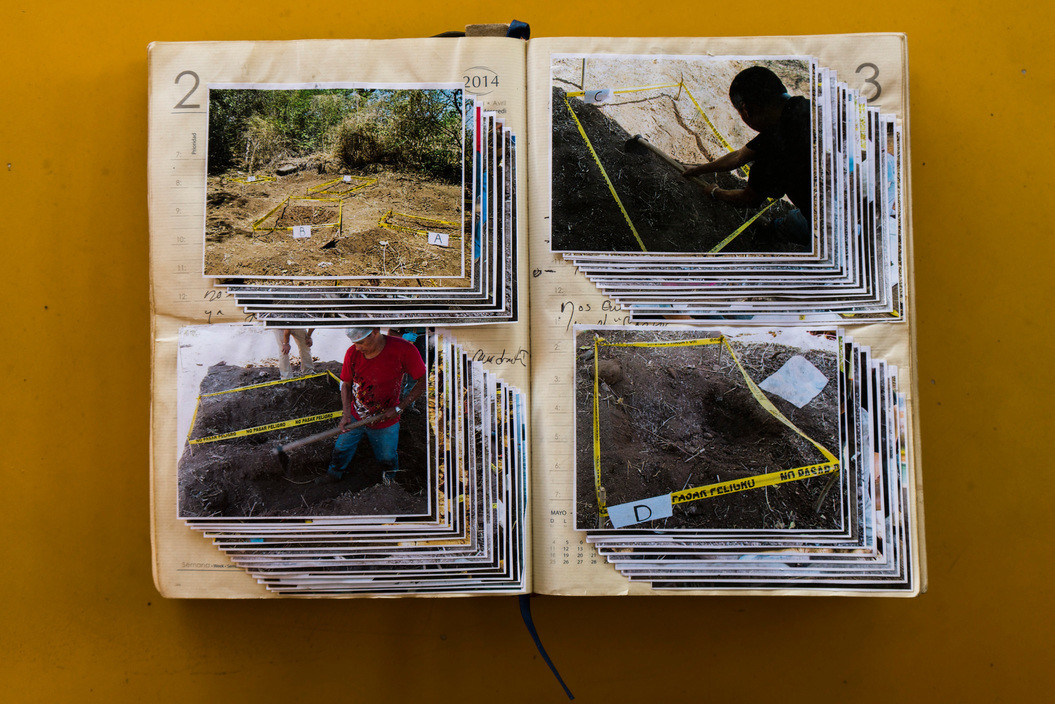

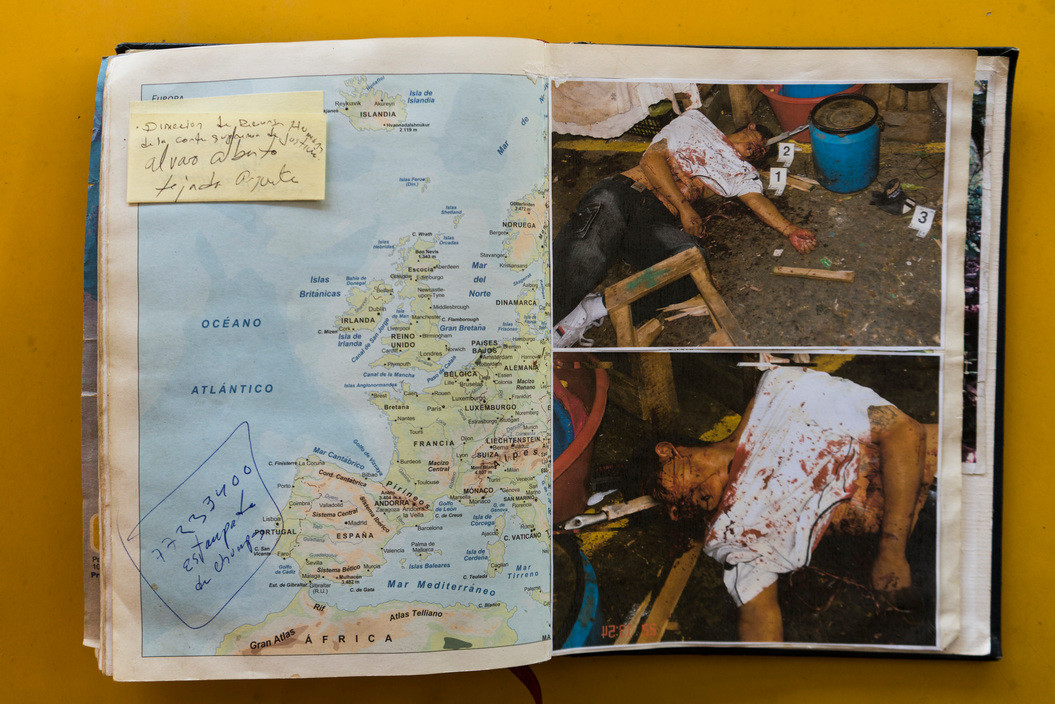

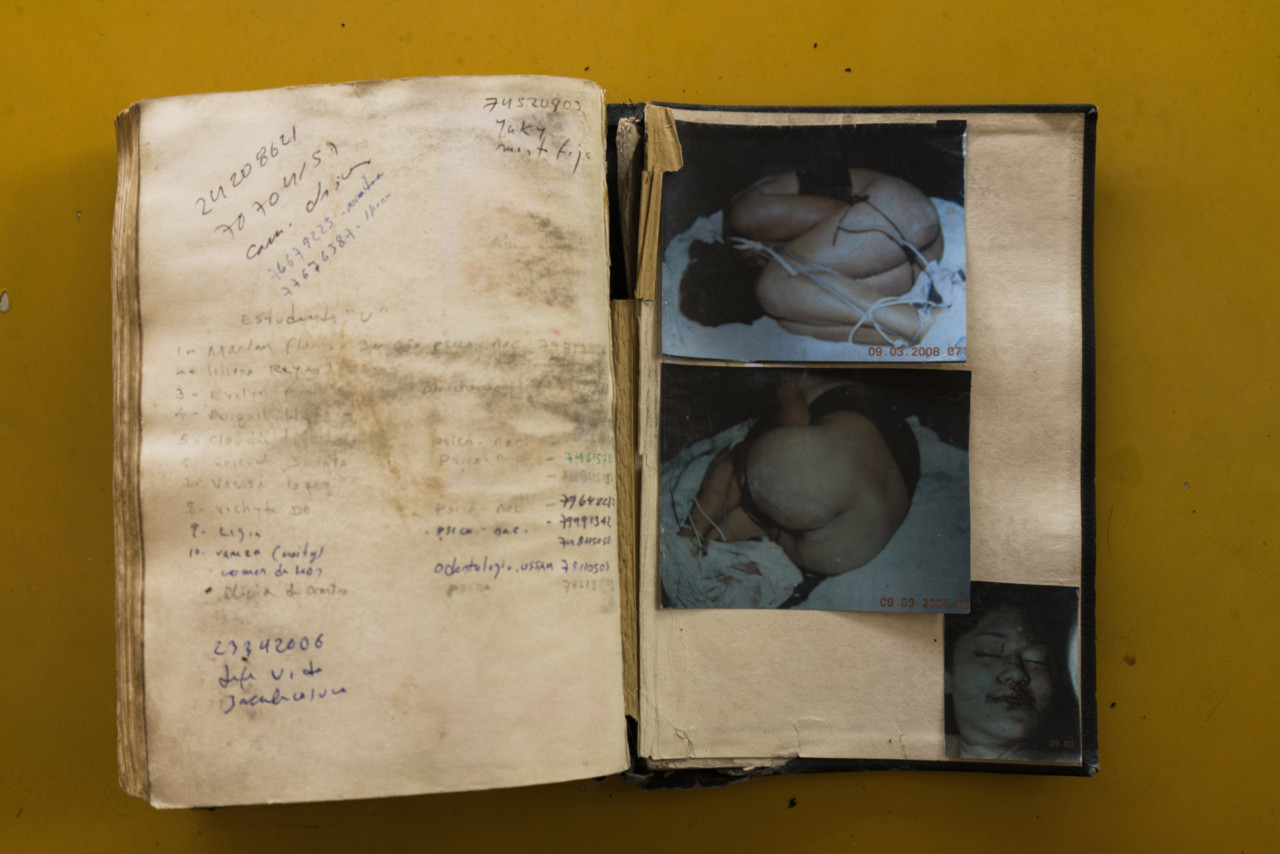

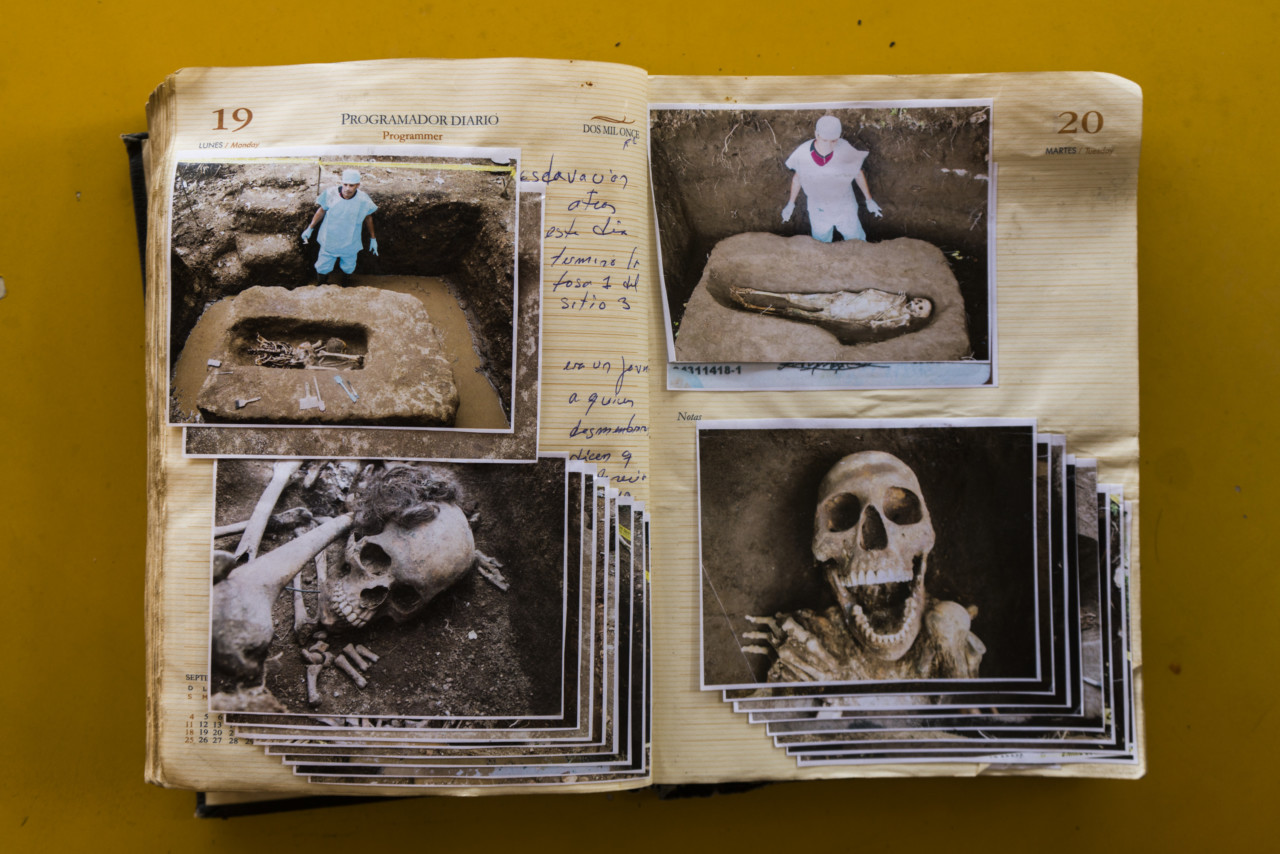

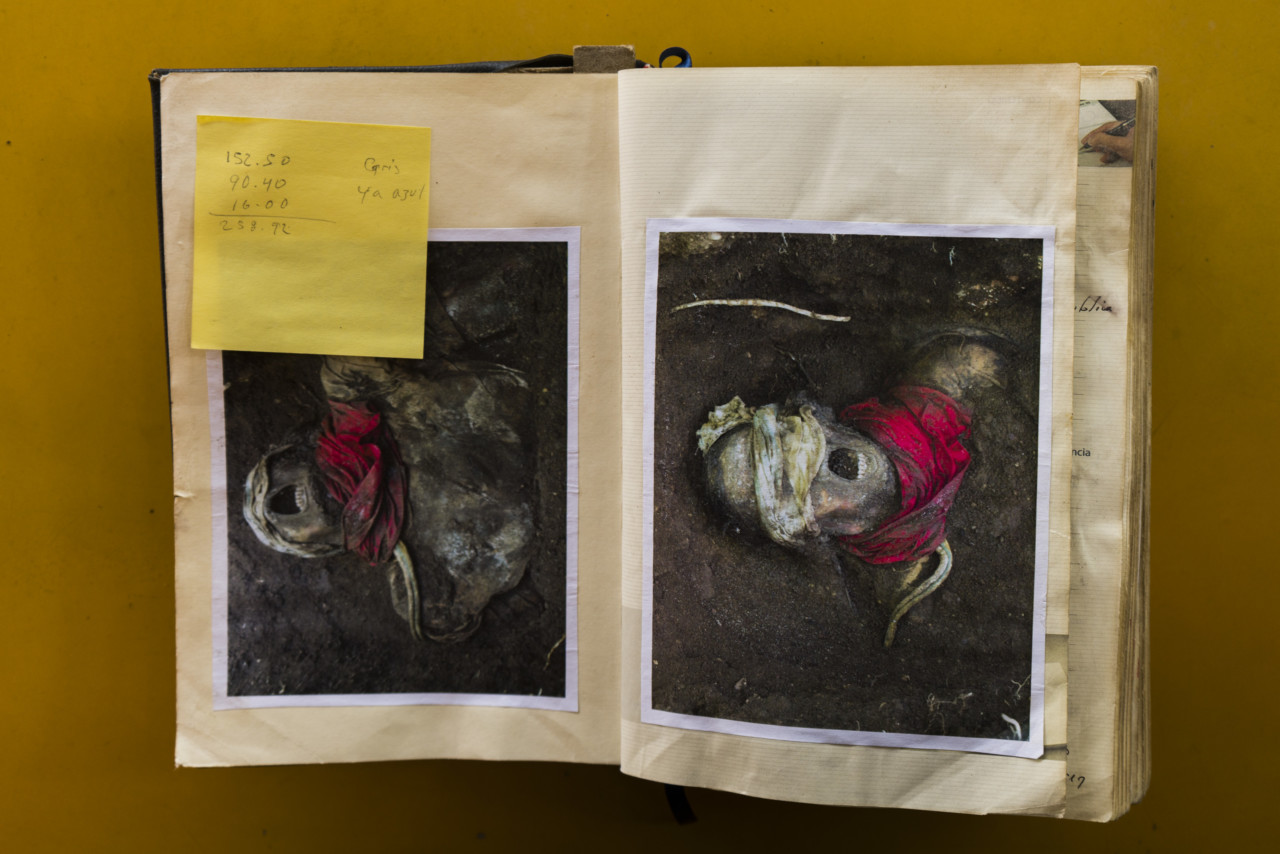

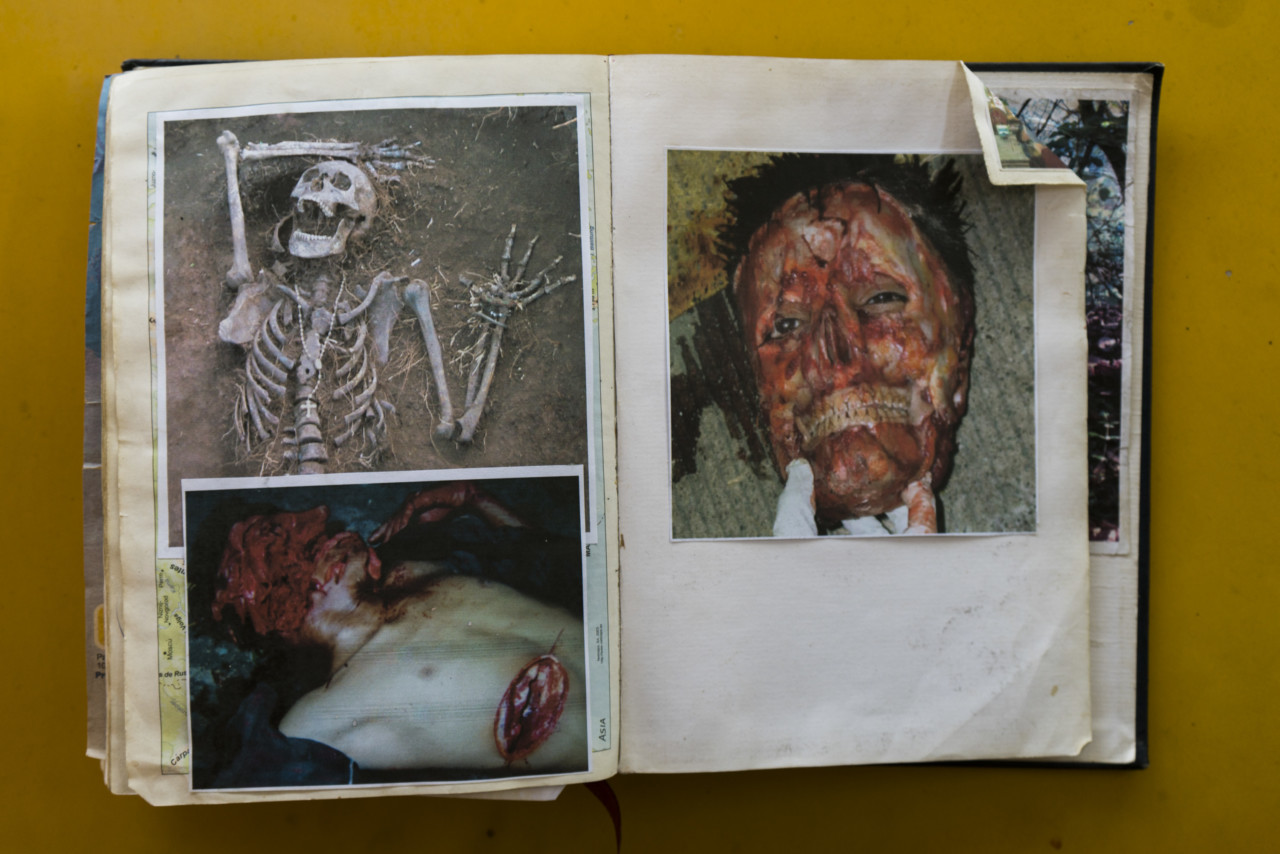

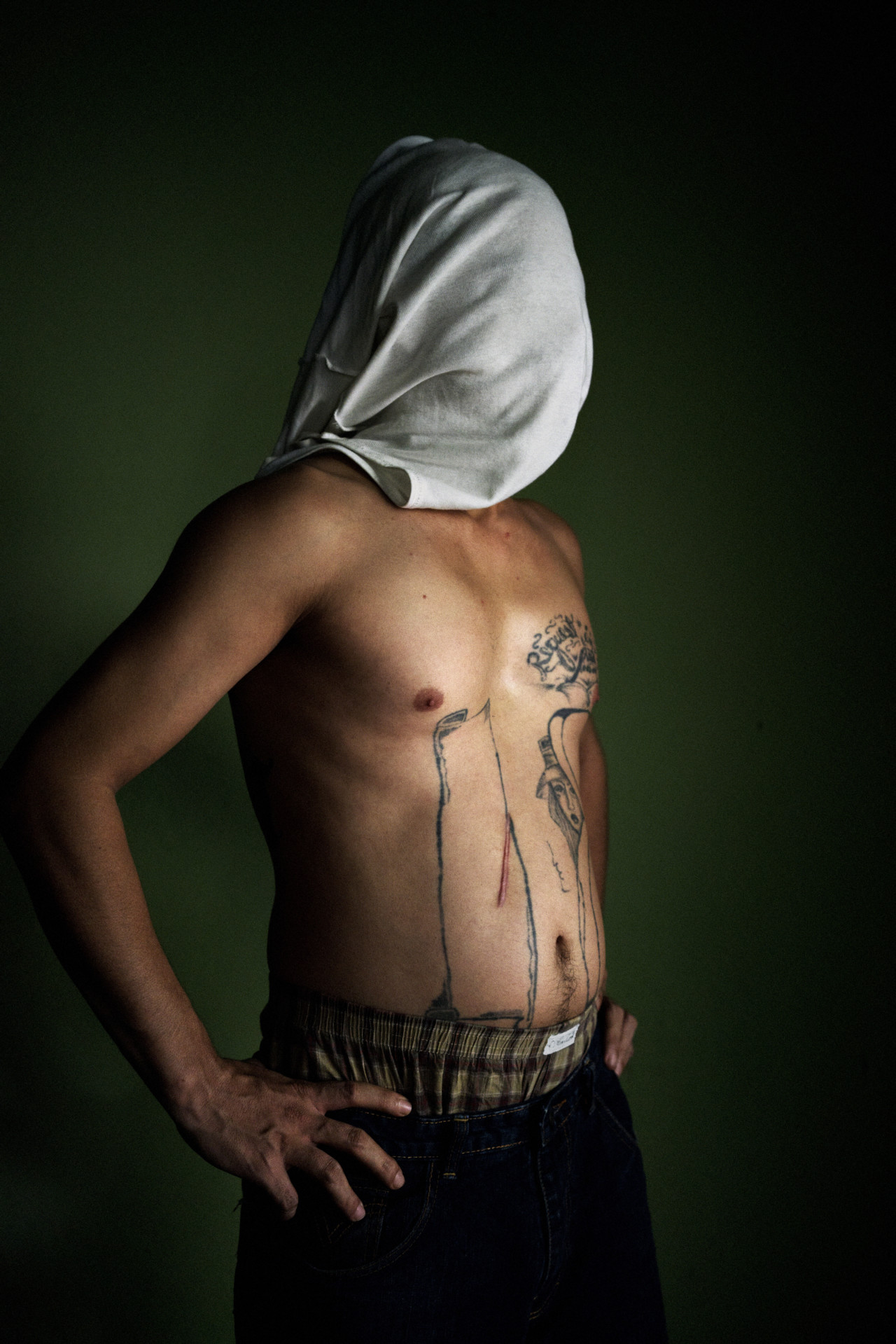

Magnum photographer Moises Saman has worked in El Salvador on numerous occasions between 2007 and 2018 covering urban crime – including one of the country’s most notorious gangs, MS-13 – and its effects upon urban populations and prisons. His work also focused upon post-war poverty, rural flight, and ultimately the mass emigration from the country in the form of the Migrant Caravan moving northward through Central America in late 2018 and into 2019. Saman suggests that to a certain extent, these unfortunate phenomena have been subsumed into the national identity: “Over the years I began to realize that these issues also intersect in ways that have transformed the social structure of the country, and in some instances they have become part of the culture; such is the case with migration.”

Seeing each of these troubling areas as interdependent in keeping El Salvador in a state of crisis, Saman notes that there are still many moments of beauty and celebration in the work he has made there: that the work is, “simply a reflection of life in a place as violent, and full of contradictions as El Salvador.” He sees these contradictions and complexities echoed in the work of Roque Dalton, one of El Salvador’s most celebrated writers.

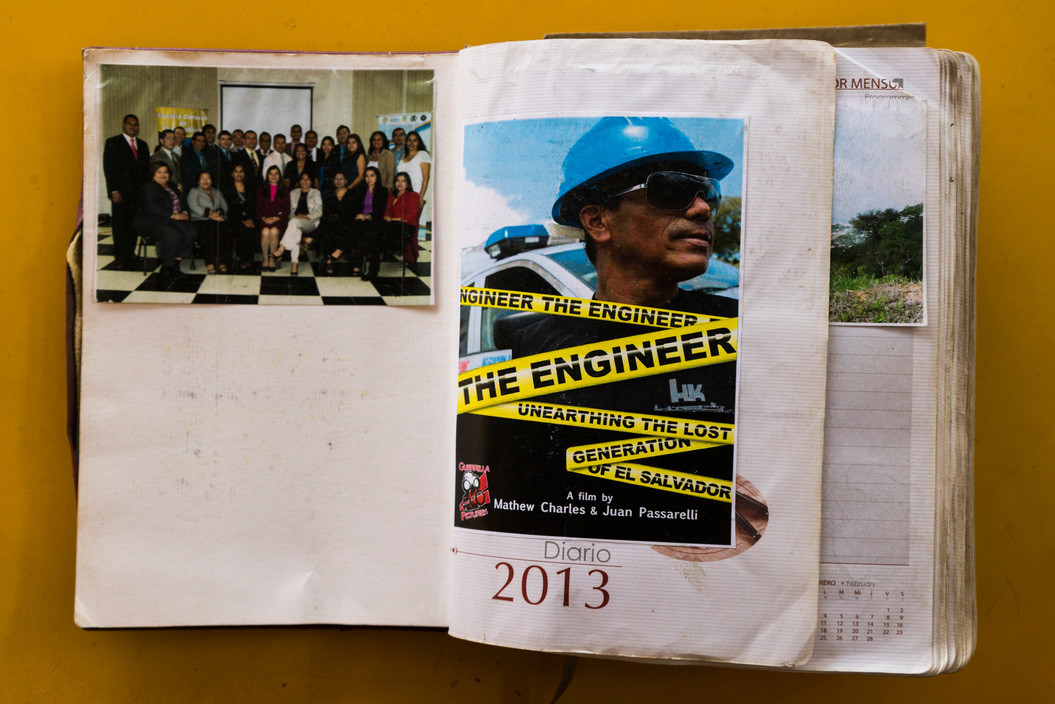

Roque Antonio Dalton García, a leftist poet, activist and journalist – exiled from the country in 1961 for his political activities – spent time in Mexico and post-revolution Cuba, where he became active within the pan-Latin literary-group, Casa de las Américas.

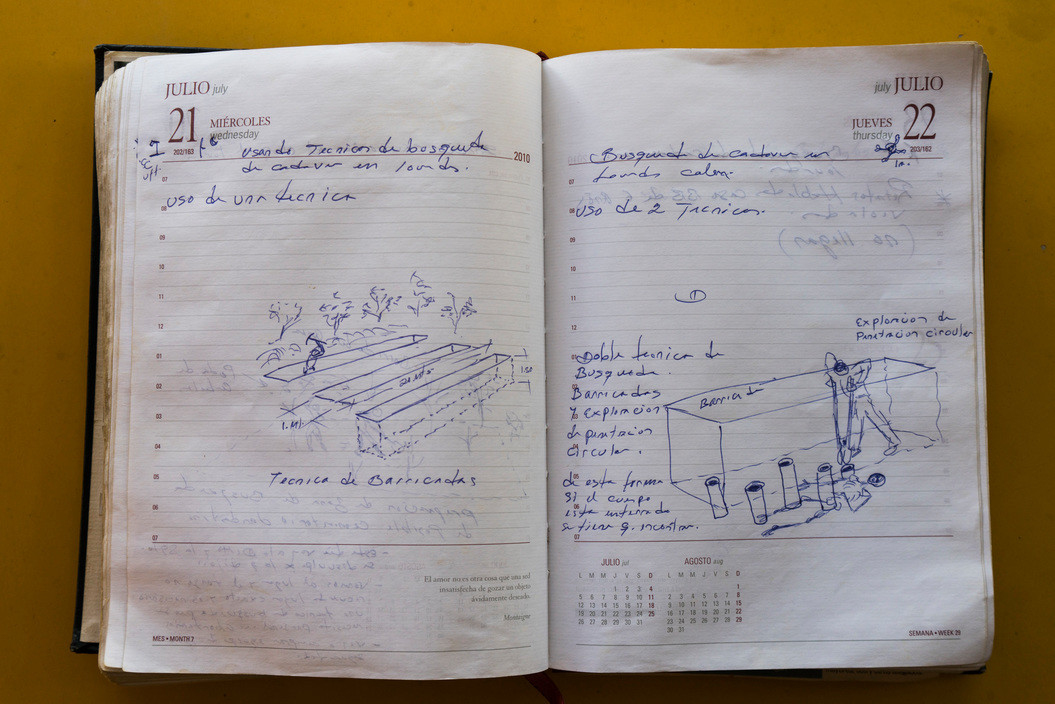

After returning to El Salvador and continuing his work in leftist literary, political and revolutionary circles, Dalton was killed in 1975, just before his 40th birthday. Though no one has ever been formally charged, and Dalton’s body is yet to be found, the killing is widely understood to have been carried out by members of the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP). The ERP was a revolutionary group that Dalton was a member of himself – which operated under the umbrella of the left wing Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front and was riven with infighting and personal animosities among high profile members.

Dalton’s work often dwells upon the state of his homeland, particularly the horrors of crime, violence, war, and imprisonment – and can be brutal in language and imagery. Yet it is also at times upbeat, and its vividness speaking of love and beauty as much as it does of pain and darkness.

Saman found this duality in Dalton’s work, and his view of El Salvador to be inspirational during his time in the country. He notes the unfortunate aptness of the writer’s difficult life and senseless death, focused as Dalton was on capturing his country’s contradictions and brutalities, “[His] life and tragic death could be metaphor for the country itself, but I was mostly drawn to the conflicting love-hate relationship that he had with his country, which he expressed through his poetry. I found this contradiction incredibly inspiring when trying to make sense of the seemingly senseless violence that continues to beset El Salvador.”

Warning: This article includes numerous graphic images that readers may find upsetting

"Who are you but this numbered monkey with a gun, shepherd of keys and hatred, flashing the light in my face?"

- Roque Dalton

THE NATIONAL SOUL

Dismembered country, you slip

into my house like a little poisoned pill.

Who are you, crawling with masters

like a bitch scratching herself on the trees

she pisses on? Who put up with your symbols

and your gestures—a girl’s smelling of mahongany—

knowing you had been stripped by the rapist’s drool?

Is there anyone who isn’t fed up with your smallness?

Anyone you can still get to honor and watch over you?

What do they call you now that, ripped to shreds,

you’re the whole future in its last gasps in the mud?

Who are you

but this numbered monkey with a gun, shepherd

of keys and hatred, flashing the light in my face?

I’ve had enough of you, my sleeping-beauty

mother stinking up the night with your jails:

I’m being eaten up inside now by my work,

This stalking that turns the good son into a deserter,

The young dude into someone dead from lack of sleep

and the nice kid into a hungry mugger.

Central Prison, October 1960

"The almond trees injured by the winter’s high tides know my grieving because they fell in it again and again"

- Roque Dalton

A DEAD GIRL IN THE OCEAN

Because you had returned the ethereal body of that girl to me

intact in the dampness

of her death, deep like the slumber of seashells,

and because you weren’t sorry for me and my mortal bewilderment

—waterspout in an eye wounded by the old search—

I was the one left out of it, the one with no right to tears.

Now it’s late for all that.

What was my crime except love?

And where did she die

except in the waters of my love?

The almond trees injured by the winter’s high tides

know my grieving because they fell in it again and again.

They are the green mirrors,

the green comforts of my distress.

The rest of you,

count this lack of wisdom among my deficits of love.

Let my steps, ocean, head towards you,

owner of my dead girl.

"Only those who live outside the prisons can honor the corpses, wash off the grief for their dead ones with embraces, scratch up the grave with fingernail and tears"

- Roque Dalton

"How can I hope, down in this rotten hole, to take in more than newsprint, the sheen of delicate black letters..."

- Roque Dalton

BAD NEWS ON A SCRAP OF NEWSPAPER

Nowadays when my friends die

only their names die.

How can I hope, down in this rotten hole,

to take in more than newsprint,

the sheen of delicate black letters,

arrows deep into personal memories?

Only those who live outside the prisons

can honor the corpses, wash off

the grief for their dead ones with embraces,

scratch up the grave with fingernail and tears.

Not those of us in jail: we just whistle

to let the sound play down the news.

"Give me your hands and some shade, but a shade gentle and cold, a darkness so thick even the fireflies have been driven out"

- Roque Dalton

THE TROPICS

Noon strikes

Like the shattering of the clay pigeons

On the breasts of the white doves as they fall.

It’s just that here everything burns:

the grass underneath your feet,

the leaves in your face, on your hands,

the water in the well that wanted to be blind.

How can anyone think of making love in this fire?

Just the same we even delight in our thirst.

(Give me your hands and some shade,

but a shade gentle and cold, a darkness so thick

even the fireflies have been driven out.)

Panting,

Your face tumbles downward, sinking into the moss,

my heart

Move your side of burning coals away from me, naked one…

DREAM AWAY FROM TIME

There was a time

when I knew a lot about the dead.

Whenever I stopped to face the night

in the last streets my sorrow

could bear,

I would make out their voices clearly,

hailing me through my country’s mist

and reminding me over and over

that some day I’d have to throw in my lot

with the infinity ice of bodies that were lost.

I knew how the dead whirled around

shaking their terrifying crystal manes,

wearing the ivy’s battle dress,

eager to use their sacred animal selves

they had saved up from this life.

God was someone dead I couldn’t understand.

Learning how to die,

that’s what life was.

Now

after new hymns, new oceans of tears,

after new eyes present behind the numbers,

from steady, cruel, never-ending bonfires,

from silent houses

where husbands love their naked brides,

from the dead body in the hospital

solid friend unmoved by my question,

from winters that bleed ahead of time,

from churches that grow on and on

over the initials of the salve, I

know

that

the

dead

raised

their

flag

and let us, miserable sons of oblivion,

to the life we still have to build,

country, sea or cosmic life,

cleansed of the old obstacles

(of darkness or special silences)

and of its solemn images

and secret outcries

hidden in the trees.

The dead are dead.

They’ve stayed behind.

Dead.