The End of Italy’s Asylums

40 years after Law 180 passed in Italy, Raymond Depardon’s series ’Manicomio’ serves as a reminder of its significance

When Raymond Depardon first arrived at the Gorizia asylum in 1977, a psychiatric hospital in Trieste, Italy, drastic reform to the mental health system was underway.

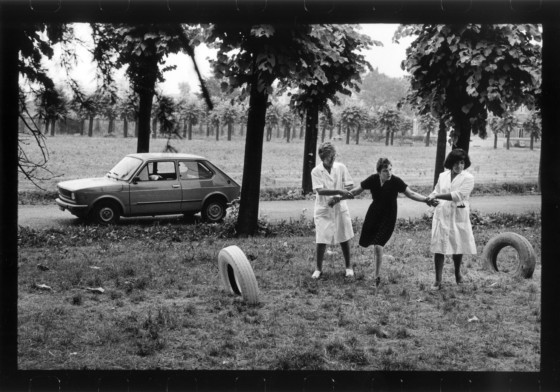

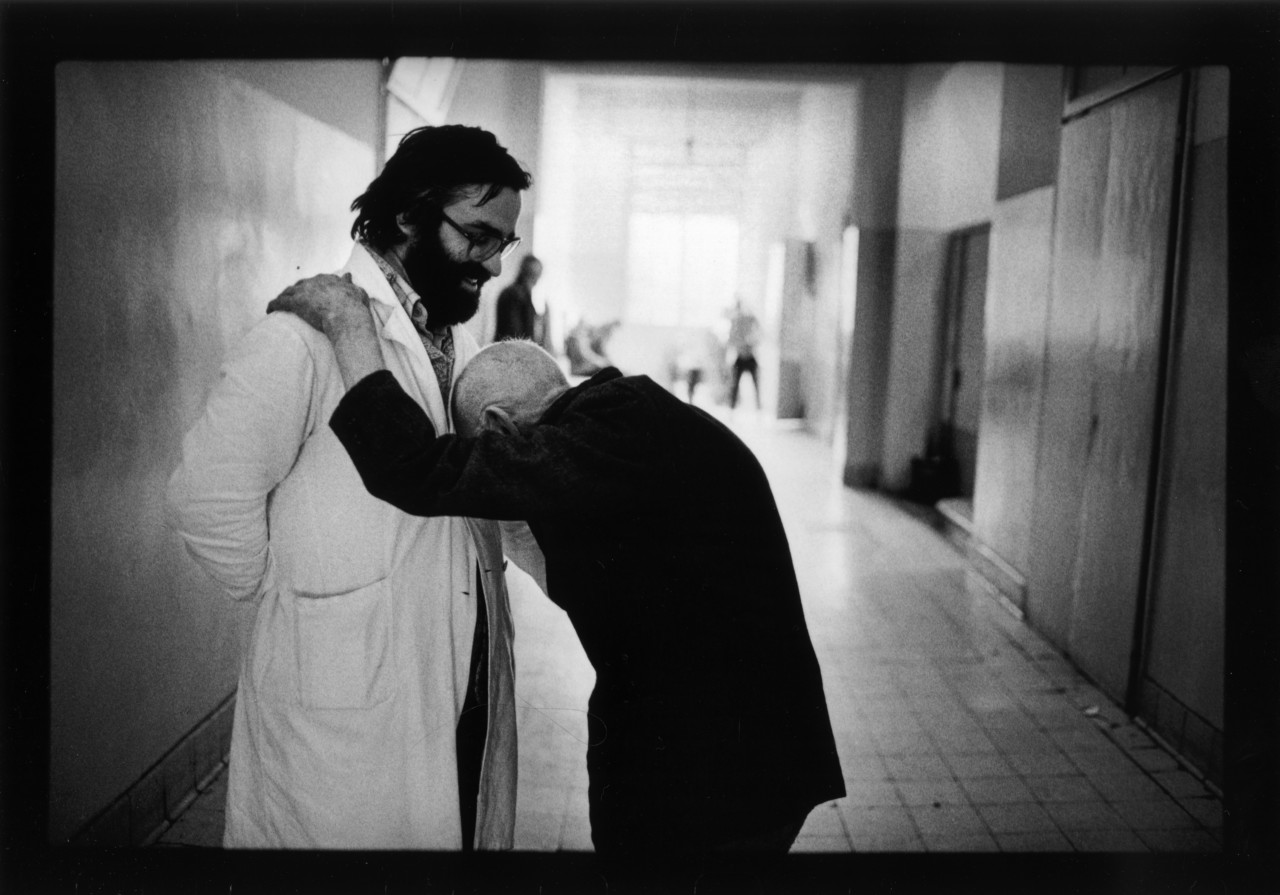

Spearheaded by its director, Franco Basaglia, the hospital was unfurling an experimental programme. It had rejected the oppressive conventions of the ‘total institution,’ and instead made the emancipation of its patients central to its ideology. In removing the straitjackets and bringing-down walls, and gently introducing dignity and democracy in patient care, Basaglia was attempting to pave the way to a more humane approach to mental health treatment.

Franco Basaglia was a key protagonist in the radical ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement that had sprung up in the wake of the social movements of 1968. Informed by authors such as Primo Levi and R. D. Laing, the school of thought drew a link between mental illness and capitalist systems, proposing that a diagnosis of ‘madness’ was historically often about controlling and isolating an individual’s suffering, to prevent societal ‘contamination.’ It argued to cure ‘madness’, a critique of the ‘sane’ was required.

"With the noise and the decrepitude of the place, I confess that for a moment I took fright."

- Raymond Depardon

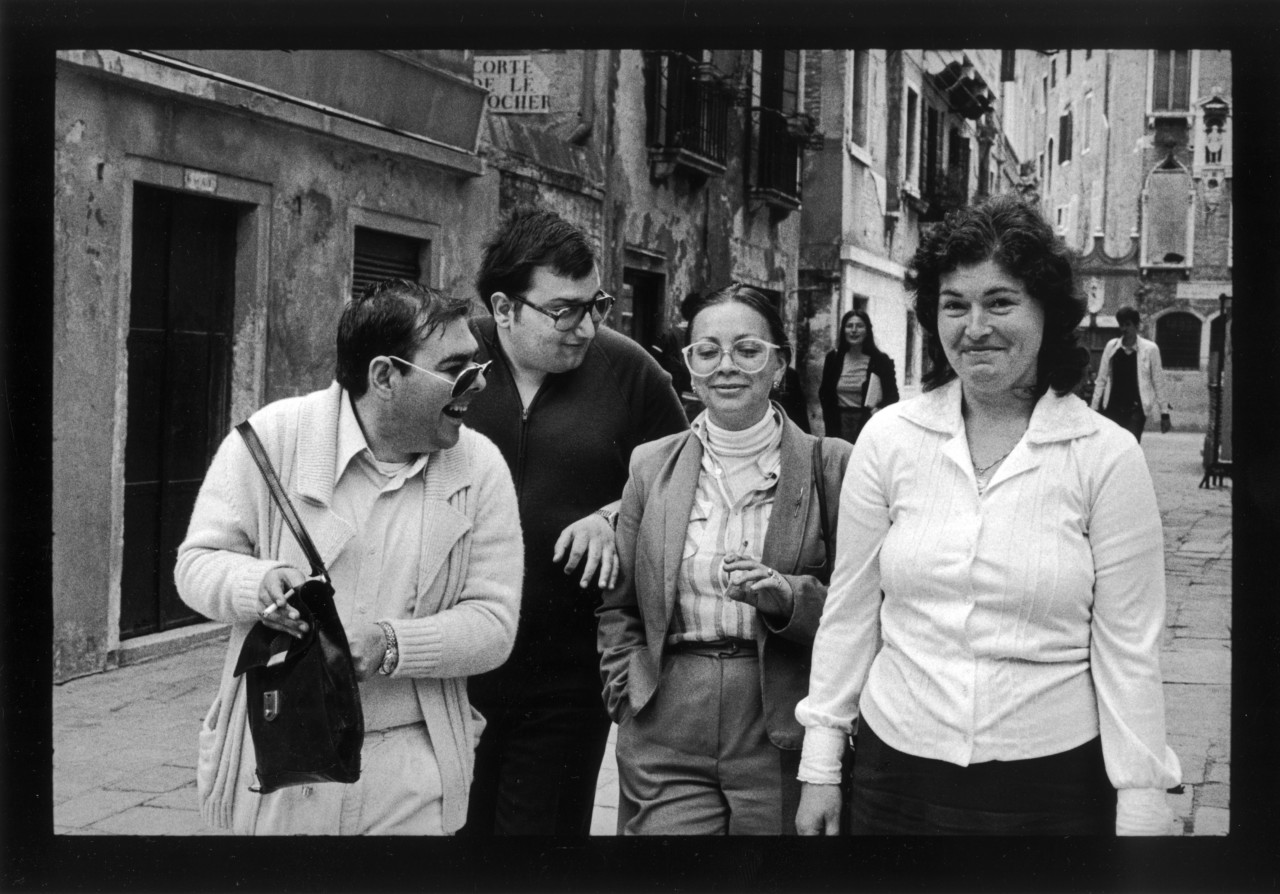

During the early 1970s, more than 100,000 patients were incarcerated, in often inhumane conditions, across Italy. It was a statistic that Basaglia had fought to change, with the results of his alternative policies taking effect over a number of years. Actively encouraged by Basaglia, Depardon set out to visit asylums in this period of transformation, in Venice, Naples, Arezzo, and Turin.

On May 13, 1978, Law 180 — also known as the Basaglia law — came into effect, which eliminated asylums for the care of patients with chronic psychosis in Italy. In their place, a decentralized community service of treating and rehabilitating mental illness was proposed. In 1982, Depardon’s documentary about San Clemente hospital was released, although it would be another three decades before he would publish Manicomio (2013), his stark report on the last days of Italy’s psychiatric hospitals.

In the below extract from the book, Raymond Depardon writes about his time photographing these sites, as a way to preserve them in our collective memory, and pay tribute to the late Franco Basaglia, who died just two years after the law was passed.

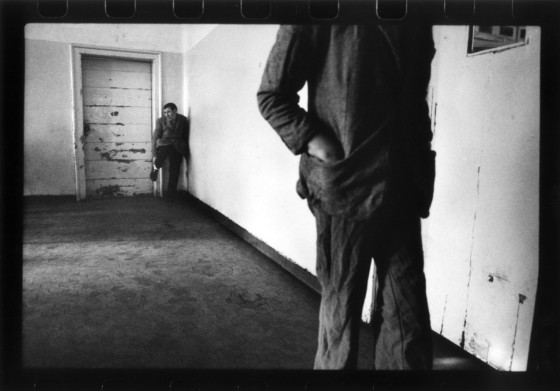

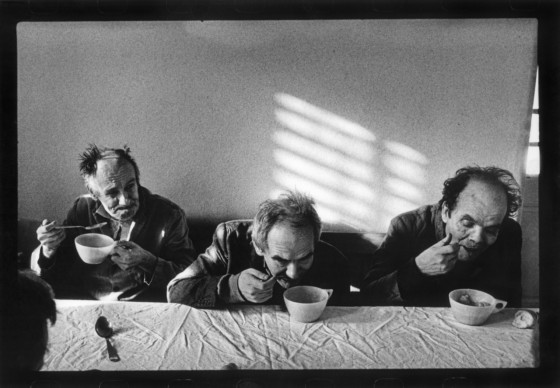

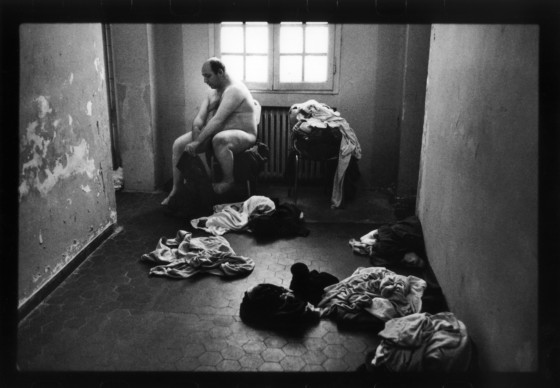

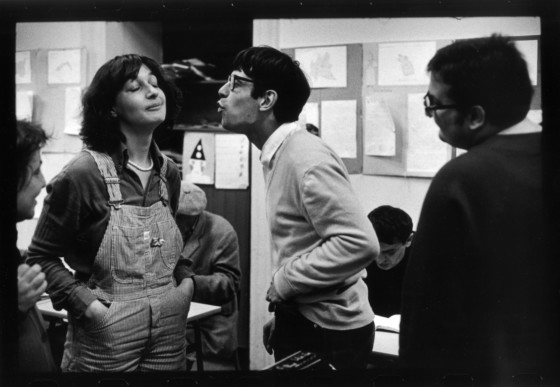

“I often went back to the old hospital in Trieste, the place called the ‘manicomio’, the ‘lunatic asylum’. One day, I followed this group coming out of the canteen. What was it about the patients that struck me: the way they looked, the clothes they wore, the way they walked? I was drawn to them. I found myself in a very old “reparto;” the door of the ward closed behind me, there wasn’t a nurse in sight. With the noise and the decrepitude of the place, I confess that for a moment I took fright. I started taking photographs, very quietly.

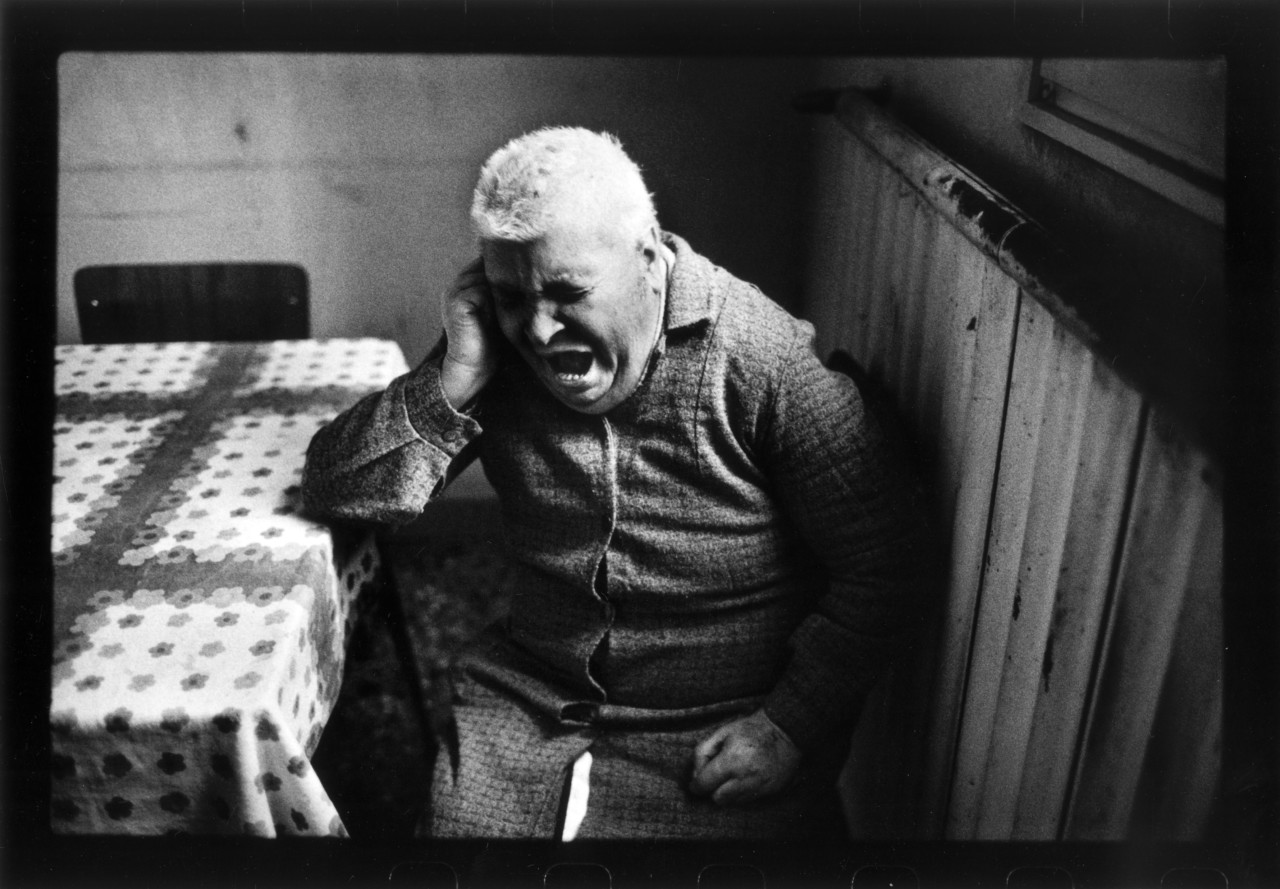

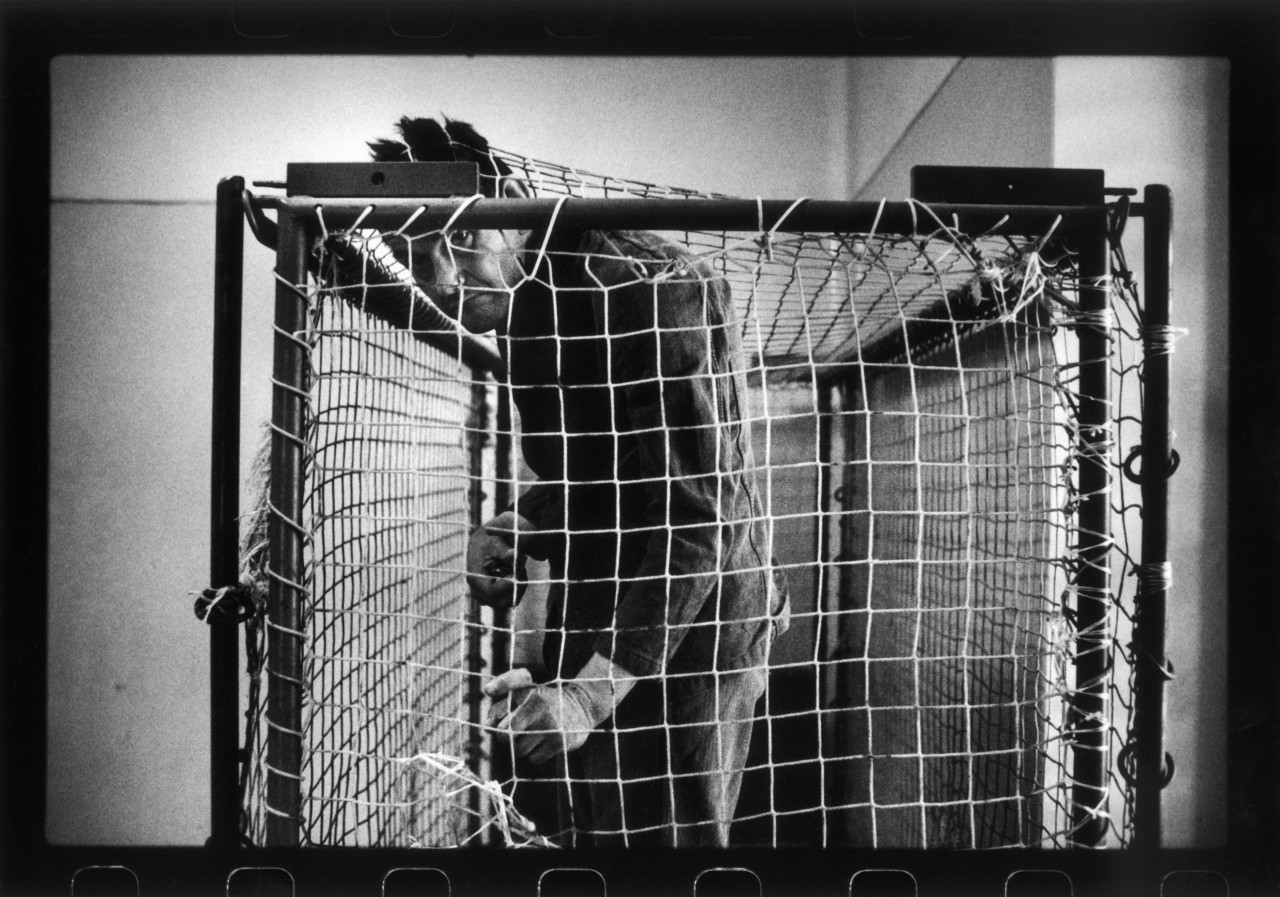

I went back there every day. I spent all my time on this ward. No one ever asked me anything. One afternoon, I heard someone shouting and pushed open a door. I found myself face to face with this man in a cage. I had misgivings about photographing him. I asked a nurse why he was given this particular treatment; he told me the man was violent and a danger, especially to himself.

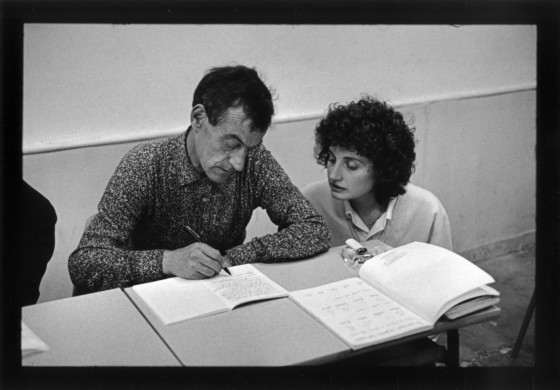

Franco Basaglia invited me to a fine restaurant in Trieste. I thought he was going to chide me for photographing this ward of ‘chronic’ patients. He made no mention of it; he talked about other things. When the dinner was over, I confessed. He reassured me immediately: “You’ll photograph patients here who you won’t see anywhere else, but it’s exactly the same in France and America. The psychiatric hospital made them that way; now it’s too late, there’s nothing else I can do for them. ” Take your photographs,” he added, “otherwise people won’t believe us.”

"Take your photographs... otherwise, people won't believe us."

- Franco Basaglia

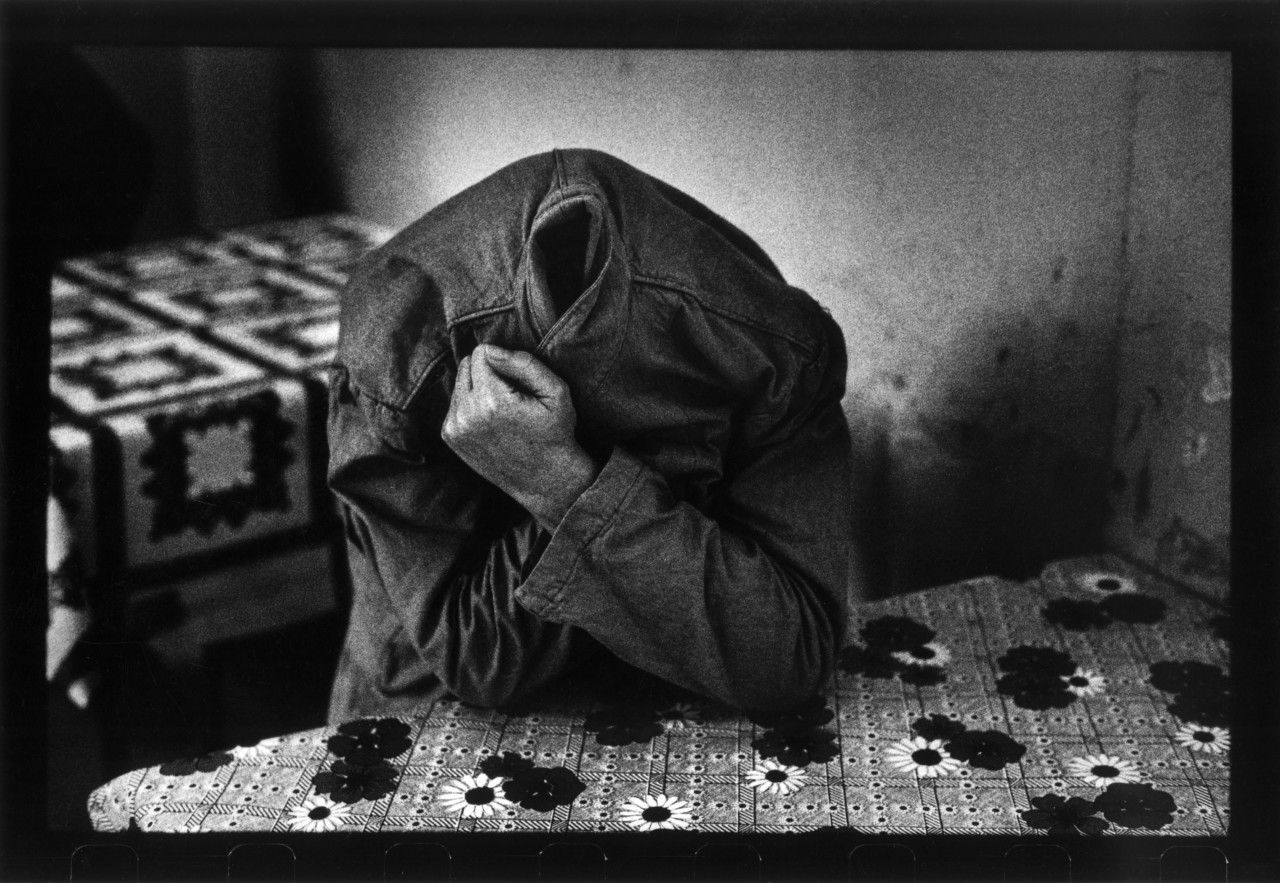

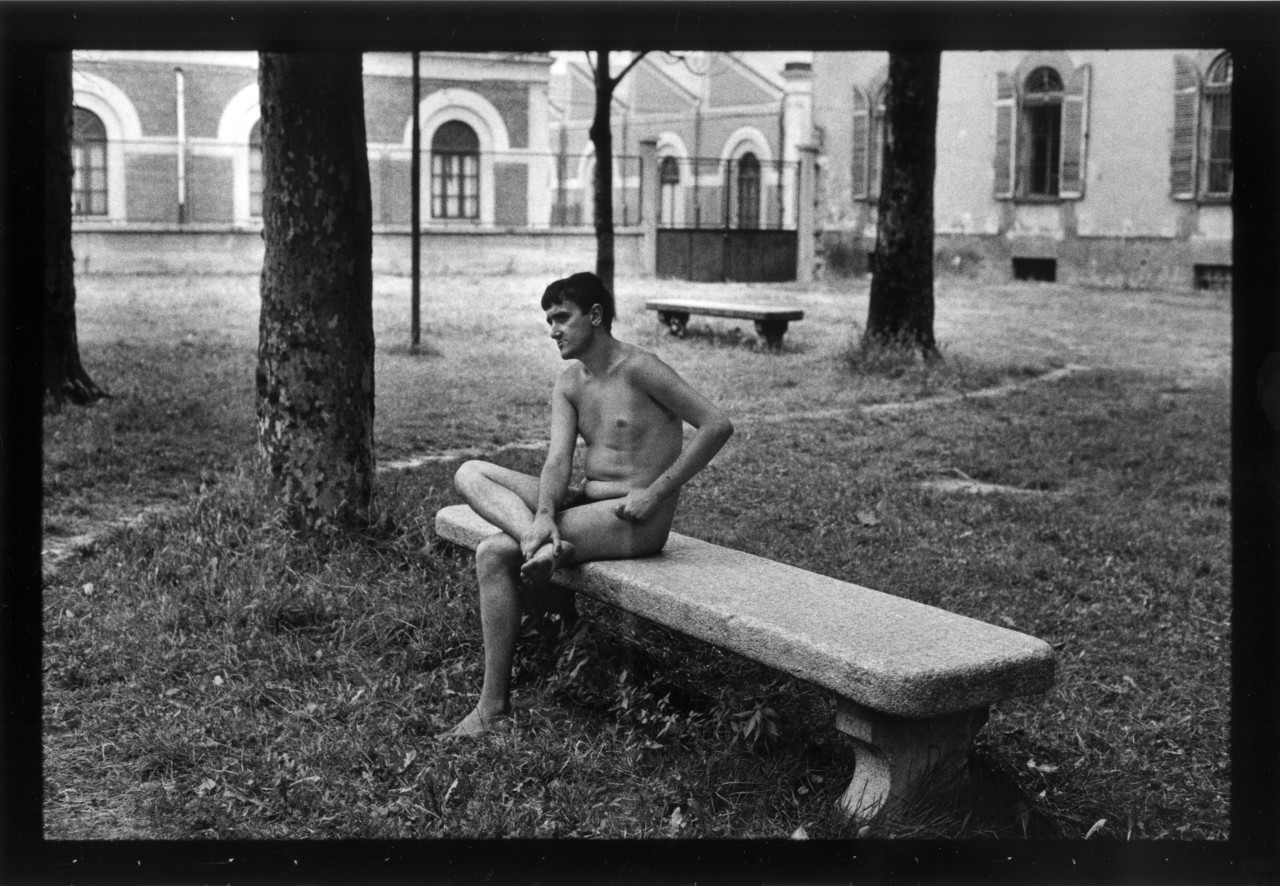

“Agostino Pirella, the director of Collegno psychiatric hospital, was surprised when he saw the photograph of the “headless man.” He didn’t know he had a patient in his hospital with this symptom. He had studied this type of case years ago, at university.

It was summertime; it was very hot. The young psychiatrists had decided to let their patients go naked in the courtyard, giving them a chance to get out of their ragged clothes.

"Raymond, there are no more photos to be taken, the prison is chemical now."

- Domenico Casagrande and Agostino Pirella

In the summer of 1981, I returned to San Clemente island frequently. The hospital was due to close and the last patients were living as a community; the Palazzo Bolda, in Venice, was used as a day center. Lomenico Casagrande was happy, there was a school for volunteers. Vittorio had drowned in the lagoon, but Gazaro was still there, all smiles.

When I asked Domenico Casagrande and Agostino Pirella what would happen next, they answered outright: “Raymond, there are no more photos to be taken, the prison is chemical now.”