“Niagara is part of American mythology. It’s a place of romance, where people go to get married,” says Alec Soth. “But when I got there my view of the place totally changed. The American side is economically devastated. It’s bleak.”

That’s how my original interview with Soth started when my article on Niagara was published in the British journal of Photography in 2006. Niagara was eagerly anticipated, the follow-up to his hugely successful Sleeping by the Mississippi.

It came out just as photobooks were beginning their ‘boom’ years, fuelled both by the internet (Google started in 1998) and the publication of The Photobook History in 2004.

What is noticeable about Niagara is its size and its quality. The book is big and beautifully bound in black leatherette. Paper and printing were cheaper, and the pragmatics of self-publishing and smaller print runs had not come into play by 2006 – especially not for a publisher like Steidl. Niagara depicts a time that now appears distant. It’s post-9/11 so the United States is already in decline, but it’s a nation yet to fully grasp the vengeful nature of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars or America’s fading voice and influence on the world stage.

When writing this review, a bleakness and emptiness indicative of this decline. is what stands out in Niagara, and that, in part, was what Soth was photographing. It revealed the human impact of an economy in disarray, which at the time was regarded as only temporary. The American Dream was always a fantasy but it was one that resonated with a global audience. In Niagara, even more than Sleeping by the Mississippi, that dream is being chipped away.

In the era of Trump, the American Dream is over, both at home and abroad. His USA is often portrayed as an isolationist nation, an impotent, toxic mess. Seen through the lens of rolling news coverage, it’s a cover-your-eyes car-crash of a country. That’s not what you see in Niagara.

Alec Soth always said he was a poet, not a documentary photographer, maybe because in 2006 documentary was seen as something quite limited. Now, documentary photography has redefined itself, it has expanded and people are more open to its possibilities. It can be poetic, it can be performative, it can be reflexive.

Niagara is part of that metamorphosis and so is Magnum Photos. New Magnum nominees, associates and members like Lua Ribeira, Cristina de Middel or Rafal Milach are indicative of this shifting rule book and Niagara is, in its sober way, a forerunner.

"Niagara is part of American mythology. It’s a place of romance, where people go to get married"

- Alec Soth

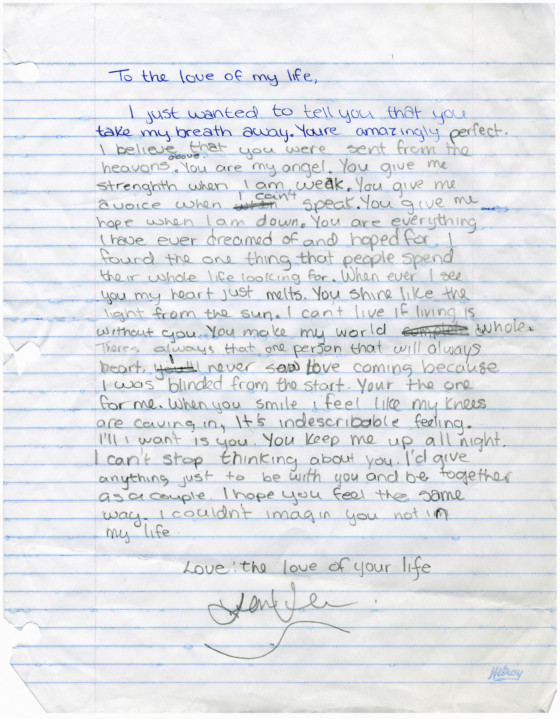

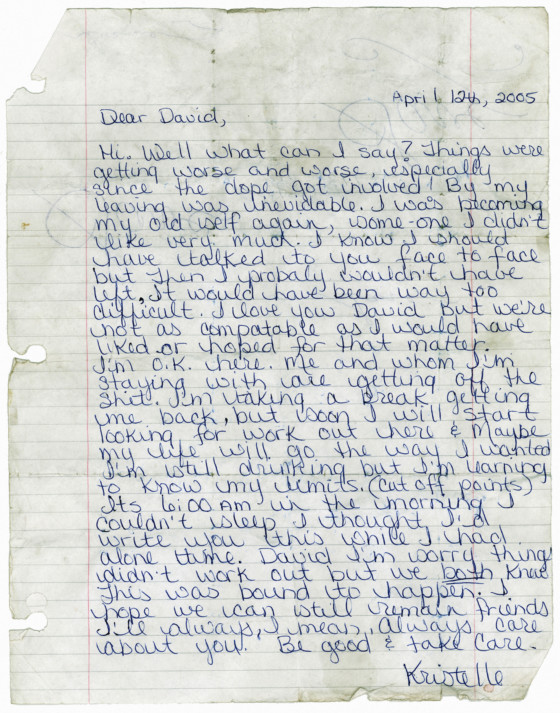

That said, Niagara still meditates on universal narratives and tells stories that engage with basic human needs. There’s love, betrayal, heartache and loss; it tugs at the heartstrings and it’s intended to. It does this through the pictures but also through the letters and notes that accompany them.

That use of ephemera is now more common in contemporary photobooks, but there’s an honesty to the letters in Niagara. They are filled with an emotional directness that still has the power to move. The same could be said about the photographs. Within the slow process of large-format photography, there is a tenderness and a vulnerability to the people portrayed in the book. And that is very rare.

Niagara is emotional, it’s awkward but intimate, and in that sense perhaps it is a reflection of Alec Soth, the artist, the poet and the man. I don’t know, maybe he’s not like that at all. But I like to think so.

Falling In Love Again: Pantall’s original review of Niagara

Alec Soth’s first book, Sleeping in the Mississippi, was so sweeping in its epic statements, it seemed that Soth had nothing left to photograph. What could he do next?

The answer is Niagara, a portrayal of the town that has traditionally been the romance capital of North America. In Niagara, Soth sets out to capture the grand passion of life, to do for love and marriage what Sleeping in the Mississippi does for the American Midwest.

“Niagara is part of American mythology. It’s a place of romance, where people go to get married,” says Soth. “But when I got there my view of the place totally changed. The American side is economically devastated. It’s bleak.”

While the American side is bleak, the Canadian side is tacky. Cheesy motels, tacky tourist sites and a plethora of fast-food outlets make the town, the Falls notwithstanding, more Blackpool or Clacton than Paris or Rome.

As Soth began photographing, he also discovered the people of Southern Ontario and New York State are a tad more distrusting and a mite more suspicious than the easygoing folk of the Mississippi states. “The longer I spent there, the darker it got,” he says. “Part of that is down to me and my nature, part of it is down to the place itself. But I also find a real beauty in that darkness.”

It is a darkness evident in Soth’s portraits which form the soul of Niagara. In Aleisha and Joe, Aleisha has a hard-edged awareness etched into her face. Joe is more feral, his face a picture of opportunism gone awry. And for all their young love, he holds her in an alleyway where fencing, cables and a coal hole are the backdrop. Similarly Michelle and Pedro are portrayed against the drabbest of surroundings. Michelle, like many of Soth’s subjects, has a fragile quality to her, something so delicate and tender it makes her vulnerable, a vulnerability Pedro, in his cone-shaped party hat, looks ill-equipped to cater for.

Melissa poses outside the Flamingo Inn. She is a big bride in a big dress and looks lovely – but the taffeta white of her wedding gown against the barren walls of her motel talks of how her dreams will fade into a reality beyond her control.

This reality hits hardest with Rebecca. Clutching a young baby, she looks worn-out and bedraggled, her hunched shoulders and darkened eyes betraying a life of lost hope and sleepless nights. Her passion spent, she stands on cracked tarmac, a rock to one side, an ugly flat-roofed building behind.

It is not all bleakness though. Occasionally the love shines through, especially when Soth asks his subjects to pose naked to make his images more intimate. So we see Michelle and James, both naked and both on their second marriage, their large bodies emanating a tender comfort and confidence in each other’s company that transcends the blandness of their motel surroundings.

Inevitably, asking people to pose naked brought trouble to Soth. On one occasion he asked a young man he met if he could photograph him and his girlfriend naked. “He said he’d do it, then I saw her and she was only 16 and too young, so I decided to photograph them outside on the grass,” says Soth. “But while I was doing this, someone saw us and called the police saying I was a paedophile, and this cop came running up to us and I had to explain what I was doing.”

The ugly architecture of Niagara is a running theme throughout the book, the regulated functionality of the town’s motels an allusion to hidden passion played out behind closed doors. At the Seneca, blue and green bucket chairs stand under stone cladding. Beneath hastily-drawn curtains, oil stained pavements are streaked with skid marks leading directly to the door – hinting at the urge of love, Niagara style.

Symbols of romance recur through all the motels but they seem fraudulent and shallow. The heart-shaped bath (and is that Soth we see in the mirror there?) and towels folded into kissing swans are overwhelmed by the brutality of the everyday – cracked tarmac, empty car parks and grey skies that hint at what lies beneath the surface of our transitory passion.

If anyone hasn’t quite got the message that love and marriage might not be all it’s cracked up to be, the love letters Soth collected should put them right. “To gather the love letters I would ask people I met in bars or donut shops if they had any old love letters I could have,” says Soth. “If you’re in a donut shop and you ask someone at the next table for their old love letters, they are going to look at you like you’re a freak and mock you. But every once in a while, someone would have them and be happy to share them.”

The most extreme letters take you straight to the point where love slides into hate. “I love you but you’ve become a piece of shit,” begins one. Others are more telling in their banalities, whether it be the woman who bemoans her partner’s lack of hygiene, or the cliche-ridden missive that reads like a track listing of a greatest ever love songs CD. “You take my breath away…, You give me hope when I am down…,” and “I can’t live if living is without you.”

“A lot of the pictures are of the aftermath of passion and love. You see couples and their love letters and then you see the aftermath and the Falls could be a metaphor for the crashing passion,” says Soth. The Falls appear throughout the book, the images gathering pace to their tumultuous conclusion. So to end the book, we see the Niagara river heading inexorably to its fate, the river collapsing into the maelstrom of the whirlpool below. First comes love, then comes the fall. Niagara is beautiful, claustrophobic and dark, an intensely poetic and thoughtful work on the disappointment of broken dreams, a work rooted in one place but universal to all.

Signed copies of Alec Soth Niagara with a limited-edition print are available on the Magnum Shop here.