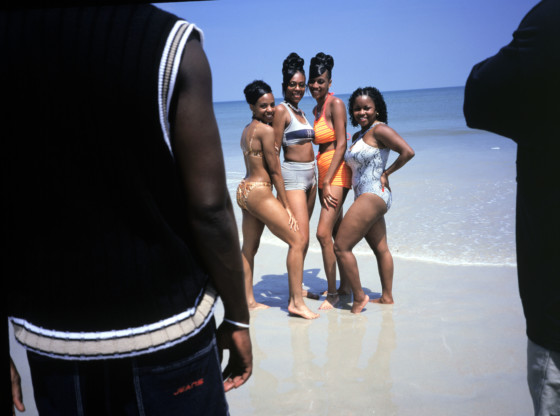

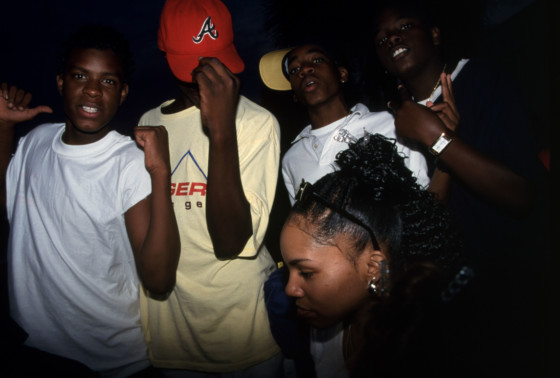

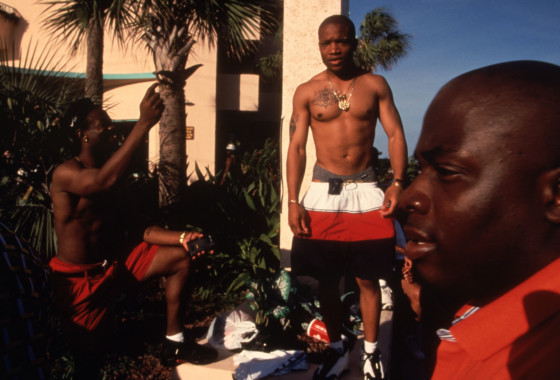

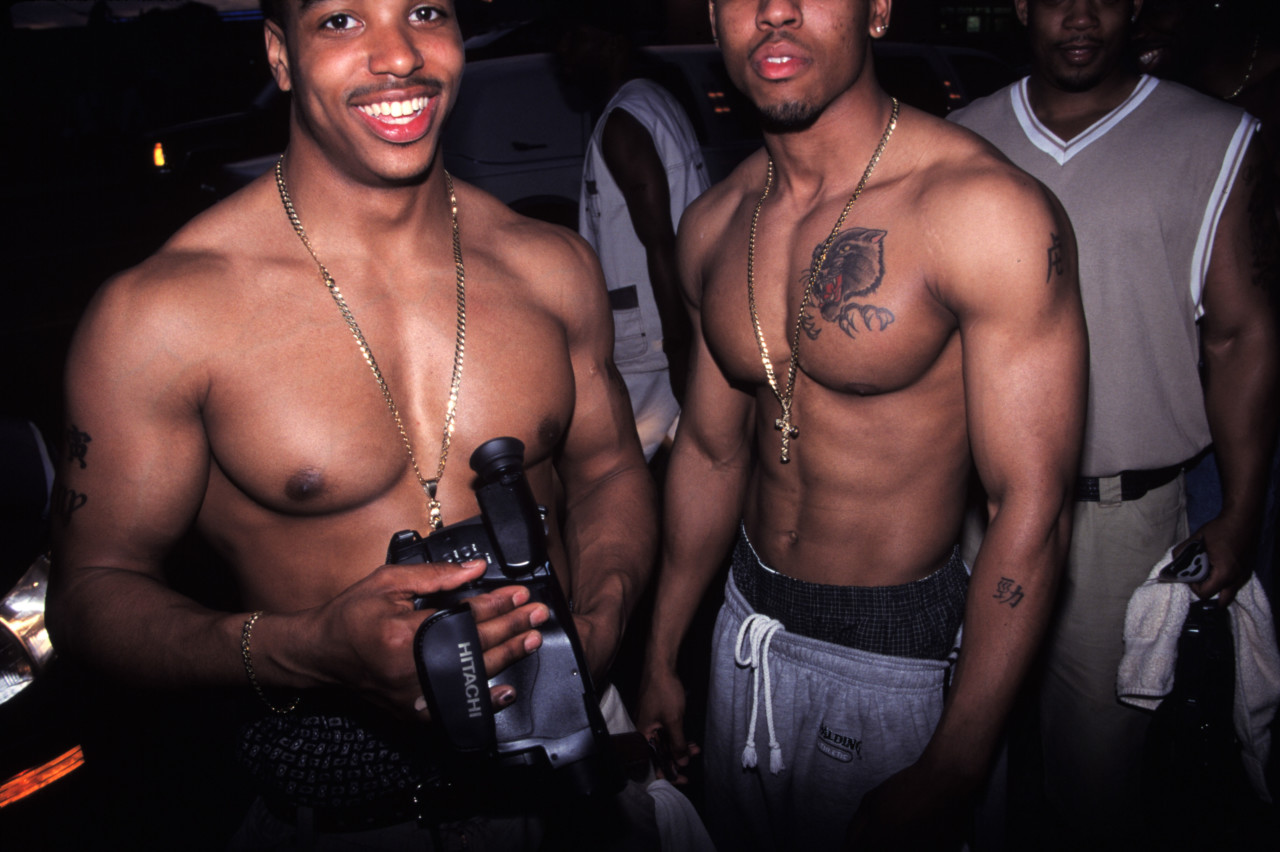

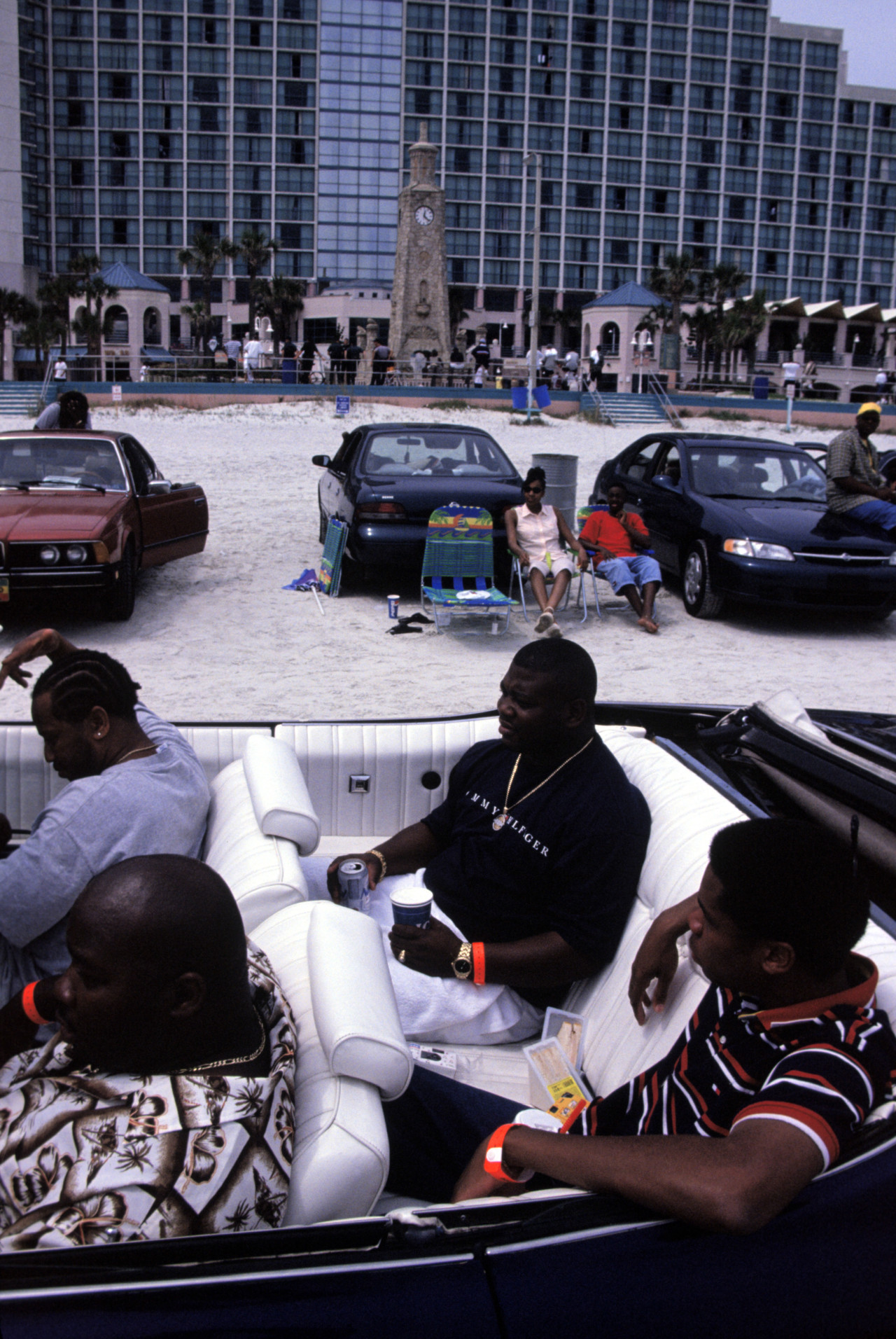

Eli Reed started his photography career in 1970 and, having reported on conflict in El Salvador and Guatemala, he joined Magnum Photos in 1982. A lecturer and teacher, Reed’s students have spanned the ICP, Columbia, New York and Harvard Universities. Today he is Clinical Professor of Photojournalism at University of Texas in Austin. Reed’s career-long work documenting the varied experience of African Americans formed the basis for his book, Black in America. As part of Magnum’s series exploring the documentation of the coast and holiday culture, Reed reflects on his 1999 photos from Daytona Beach, of black spring breakers.

What was your experience of spring break like, and how did you come to be in Daytona?

There were a few different versions of spring break, the Canadians seemed to come down first – earliest in the year – maybe because it’s colder up north? Then the white collegiate kids come along, followed by the black students last.

I was in town for a workshop and while there I was visiting the curator Alison Nordström, who had a place near Daytona. The first time I had been in Daytona was for white spring break. I had just got back from a National Geographic trip to Africa, so I was jetlagged and had picked up some bug, I wasn’t feeling so hot.

The white spring breakers were crazy. You know, all the stuff you associate with spring break – the partying, and the occasional death when some kid tries jumping off a balcony or something crazy. I got some great pictures from that first trip. One in particular comes to mind, I was photographing a wet t-shirt contest, and there’s this kid behind one of the contestants with boner! Just stood there with a boner in his shorts! I didn’t spot it until years later…

In comparison to that, your photos of black spring break while very much vacation photos, don’t have that feeling to them. They are calm, almost serene images.

The thing is that really – looking back on it – the white students seemed, well, much stupider! Black spring break was crazy in its own way, but the black students seemed to be a bit cooler, they were still young and reckless, but they didn’t seem so into doing really stupid stuff, like jumping off balconies.

Do you think that also comes from the way you shot the black spring breakers, with that respect you are famous for in your work?

I go with the flow. I’m not trying to do a hatchet job on anybody. I have respect for what people are doing in general. And that goes for kids on break too. The white kids, good God, some of them were torn down drunk, female students laying on the ground, torn up from heavy drinking, being dragged along the street by their friends…

I just didn’t see that with the black spring breakers at all. They were hanging out – and it’s not because I am black that I am saying this – it was just noticeably different in mood.

I wasn’t really prepared mentally for it at all. I didn’t know it was happening! I was walking down the street after dinner and found these black students hanging out by the water. I had my camera on me, as I always do, and it was just one of those things. I saw it, and ‘boom-boom’, I took the photos.

There’s one photo from there that sticks out to me in my mind, of a guy leaning against a pole or lamppost, with a few black girls walking by, and one of them has this bright orange wig on – that image to me sums it up for me, it is just cool.

"I am not trying to do a hatchet job on anybody. I have respect for what people are doing in general. And that goes for kids on break too"

- Eli Reed

You have worked in Florida a lot – does the state in general hold a certain allure for you?

The first time I went to Miami was for the Liberty City riots, in 1980. I arrived after seeing the news on TV, and I had to get a picture in time for the next morning’s paper. I remember the only rental car I could find was a white Thunderbird! Nice target in a riot.

Anyway, I got the pictures and the newspaper used one. That job was actually effectively my first warzone work, there were snipers, and trigger-happy state police who were far more dangerous than the snipers, it was a mess. I was there five days, then the paper called and said come back. Well, of course I went back out again, and that’s when it got really physically dangerous. We were shot at and all kinds of nonsense. That was my first time working in Florida!

"[Florida] was actually effectively my first warzone work, there were snipers, and trigger-happy state police who were far more dangerous than the snipers"

- Eli Reed

Another Florida experience was when I was working on the John Singleton movie Rosewood. It is a very emotional subject for anyone who’s African American – it’s about the 1923 massacre of black residents in a Florida town by the white community. We were shooting in an area that was quite heavily Ku Klux Klan, in fact the KKK came to the production office two weeks before filming to take a look and see what was going on! It was pretty rough working around there, there were real concerns about Klan attacks on the set or crew driving to and from it.

I recall one scene we were shooting where ‘the Klan’ were celebrating after doing some damage, and it was for sure in my mind that some of the cast, those extras, were real Ku Klux Klanners… Usually when they say ‘cut’ on a movie set everything stops immediately, the AP had to shout ‘cut’ like three times to get them to stop enjoying themselves so much…

I worked on the movie 2 Fast 2 Furious in Miami too. That was more about the high life. There were a lot of sexy girls, fast cars, you can’t get better than that!

Florida is such a crazy place. But I think I try to take places as they are, and to not assume anything about them.

How do you see the Daytona work as fitting into your career-long focus on the experience of African Americans?

I immediately grasped that difference I mentioned before – between the white and black students – and I wasn’t expecting that. I really thought it would be pretty much all the same. But it was like jazz compared to rock n roll. I like rock n roll, but you know what I mean?

There was a certain awareness and maturity in the black gatherings, a sense of supportiveness among the black kids. They seemed to be looking out for each other. There was a feeling of responsibility, not to do damage to yourself, or to your reputation. I had great respect for it. The white kids didn’t seem to have that worry! The juice was definitely flowing differently.

There’s a lot of talk about white privilege today, and thinking back to that, you know – it was on display in a way. If you have privilege you should use it for the best, for society, and there is a responsibility that comes with privilege. I saw what I saw, and I tried to document that. I didn’t go into it expecting to take the photos I did, but you couldn’t help but see the comparisons between the groups. It makes me wish I had done more on it at the time.

"Photographers are like doctors: you engage in something and you try to do no harm to the subject"

- Eli Reed

That contrast is in the photos – some of which clearly dwell on the interaction of white vacationers with the black students. It’s also mentioned in your captions explicitly. How does documenting that tie into your wider feelings about your obligation and outlook as a photographer?

That interaction was there. I would have been irresponsible if I hadn’t photographed it, and I would have felt like I missed something.

You go shoot something and at some point afterwards you always think, ‘Oh God, I missed this, and I missed that’… I have photographed a lot in The South, and a part of that was of course photographing the interaction between white southerners and blacks. But it’s really about not missing things, giving all things equal importance. You hope that you capture the overall feeling, and you steer by gut reaction.

The good the bad and the extraordinary happen all the time, and it is amazing to be able to see it. If you don’t document things people can say it didn’t happen. Those crazy or miraculous things which show what it means to be a human being? As a photographer you can capture those intricacies of life, of time, and people that you might not even have imagined.

The first thing is being true to what happened, without making stuff up. Photographers are like doctors: you engage in something and you try to do no harm to the subject. The truth will set you free, as long as you work at it and take responsibility for it.

You have to honour what you see. Keep it real, that’s what’s in the back of my head when I work: “Keep it real, keep it real, keep it real!” It’s easy to screw up.

"That’s what’s in the back of my head when I work: “Keep it real, keep it real, keep it real!” It’s easy to screw up"

- Eli Reed

In a wider sense, what’s important about photographing people at leisure, on vacation?

It’s about what is a presumed quality of life and how particular societies engage, either with fellow members of that society, or alone. How they step away from themselves in order to recharge batteries. Their participation in these varied ways of relaxing can reveal much of what is a valid release to participants. It shows what is acceptable as far as they are concerned, what will give them a restful preparation for re-entry into the ongoing various norms of living their lives.

That is what most vacation photographs are about. A proof of life and of where you experienced that life, which can be held close inside one’s pleasant memories of heart and mind.

It is a continuing restorative resource of positive mental energy that allows a person to keep moving, and possibly looking forward to that next vacation.

Published as part of Magnum’s summer series of stories: ‘Life by the Sea: Exploring identity through society at leisure and the pursuit of pleasure’. See the rest of the stories from the series here.

Browse the Life By The Sea poster and fine print collection on the Magnum Shop