The Source of Light

Micha Bar-Am's new book is a document of both communal life, and loneliness, in the Kibbutz

Born in Berlin, Micha Bar-Am immigrated with his parents to Israel (then Palestine) in the 30s and grew up in Haifa, and after participating in the 1948 war of independence became a co-founder of a kibbutz in the Galilee.

The Hebrew word kibbutz – which translates as a ‘gathering’ or ‘cluster’ – is the name given to collective communities in Israel – originally primarily agricultural in nature, which have existed since 1909.

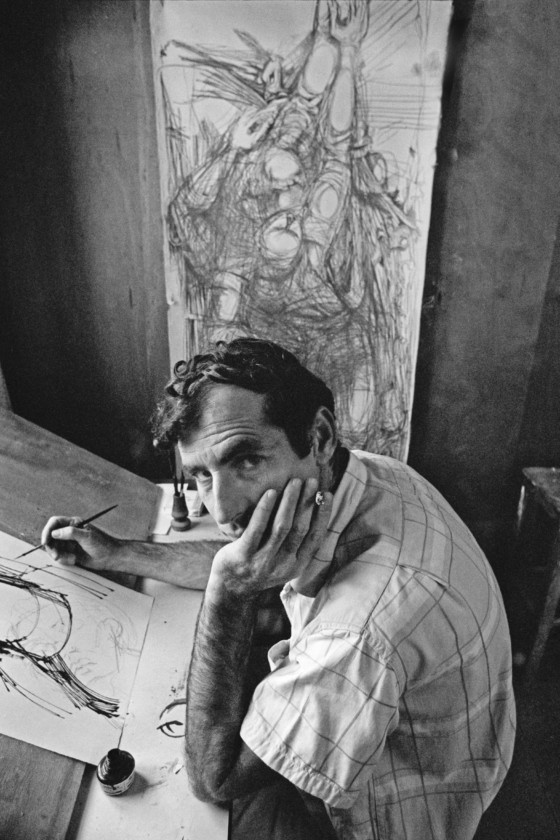

Bar-Am was born at least three times, according to an introductory text in his new book Kibbutz, by Guy Raz: “as a human being in Berlin (1930), as an Israeli upon his immigration to Palestine (1936), and as a photographer in Kibbutz Gesher HaZiv (1953).” Inspired by magazines like LIFE, Bar-Am grew fascinated with photography and became a passionate chronicler of the complex multi-layered conflict in the Middle East .

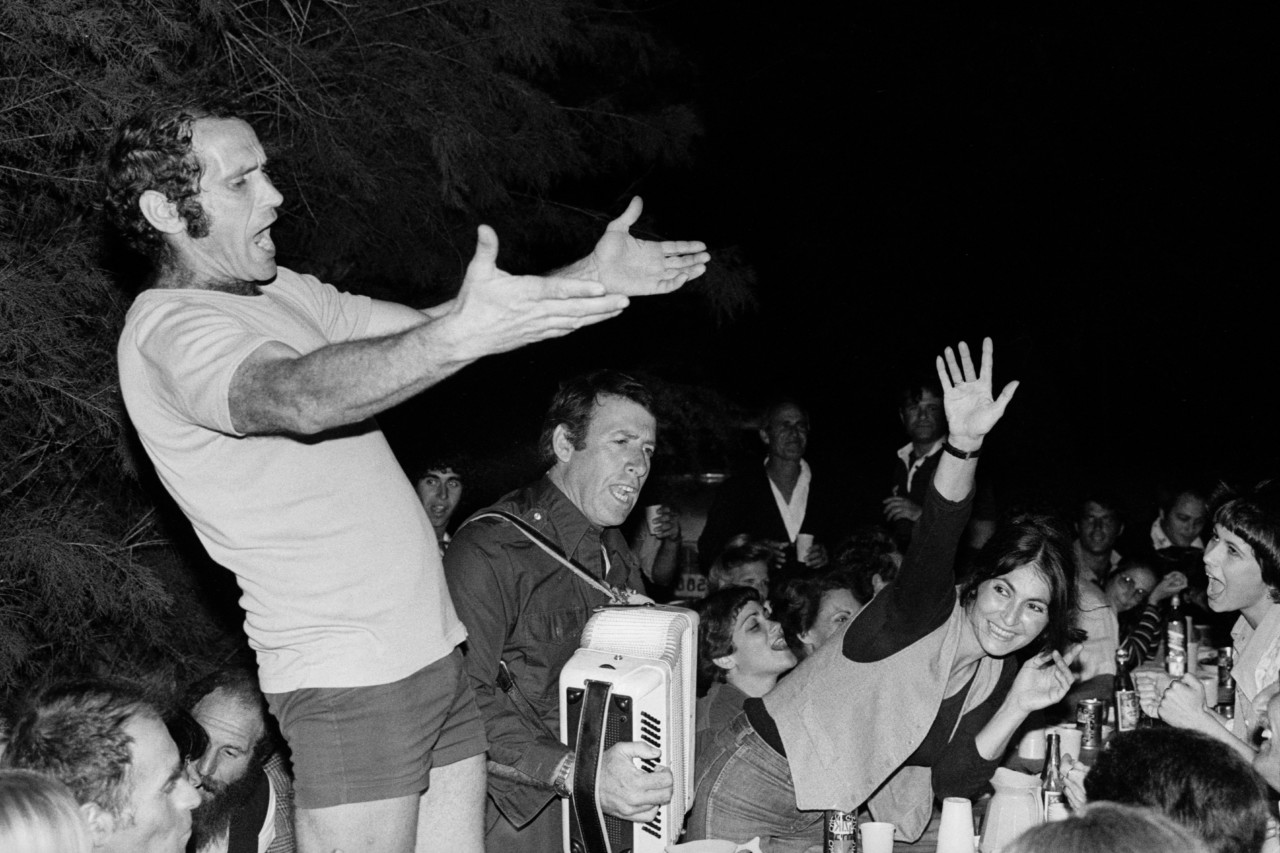

In the early ’50s Bar-Am started experimenting with photography, documenting individuals and landscapes, daily life, festivities, communal agriculture and industry within the Kibbutz. He also photographed the surrounding land, as he explains: “My Arab neighbors and their villages were always a close subject of my photography and led to relationships and friendships that continue through our kids still today.”

In the mid ’50s a growing desire for adventure led Bar-Am to take part in the historic search for the Dead Sea scrolls in the Judean desert. In 1957 he left the Kibbutz that had been his home in order to make photography his primary focus.

Here we reproduce a short text from Kibbutz, by Israeli author Yael Neeman. The book can be purchased in Israel at the Beit Shturman Museum, Kibbutz Ein Harod.

Micha Bar-Am says that he became a photographer in the kibbutz; there he realized he was a photographer. He says that he knew he was a photographer when he purchased his first Leica camera, having seen the Americans’ Leicas at Kibbutz Gesher HaZiv. “Before I purchased a Leica, I did not consider myself a photographer,” he says, “even though we had a camera at home since I was 4. Even in Germany.”

When he knew he was a photographer, he had to leave. “I always wanted to be somewhere else, so I joined the search for the Dead Sea Scrolls in the Judean Desert and the Sinai Campaign (Suez Crisis) as a photographer for the IDF weekly Bamahaneh. I accompanied various delegations, and always returned to the kibbutz. I fought for my status. I asked the kibbutz for a day or two for photography, because I took photographs in the kibbutz too, and the members asked me to take their pictures. At some point I started asking for a little more money so I could experiment in photography, which made me agonize. It wasn’t approved. I guess this was the main reason for my decision to leave; I realized I wanted to take photographs and travel the world. I left in 1957.”

He took still photographs portraying silent conversations. Why depict a conversation if it cannot be conveyed in a picture? But lo, it can be conveyed, and it is so very lively. Precisely because the conversation is silent, you can see the people and their surroundings; not the “kibbutz industries” or the “work places,” but rather something else: the workers, the men, the women, the bustling dining room. It is seen through the windows behind the protagonist at the heart of the picture — a woman with a baby sitting outside; perhaps she had to go out because the baby started crying during the holiday meal. The cooks chat by the giant pots in the kitchen. Women talk and smoke before getting into the truck to do an extra shift. Mothers and daughters talk on the sidewalk; talking and laughing.

A photograph of the same, familiar, generic tree-lined avenue, the one of “We are Both from the Same Village.” The same two men, the same cypress trees, the same paved road. But in the photograph they are seen from the back. No forelocks in sight. They don’t walk together. They go neither to war nor to work, but rather to the laundry, the washing rolled up in bed sheets on their backs, and the white sheets glow on their backs like fireflies.

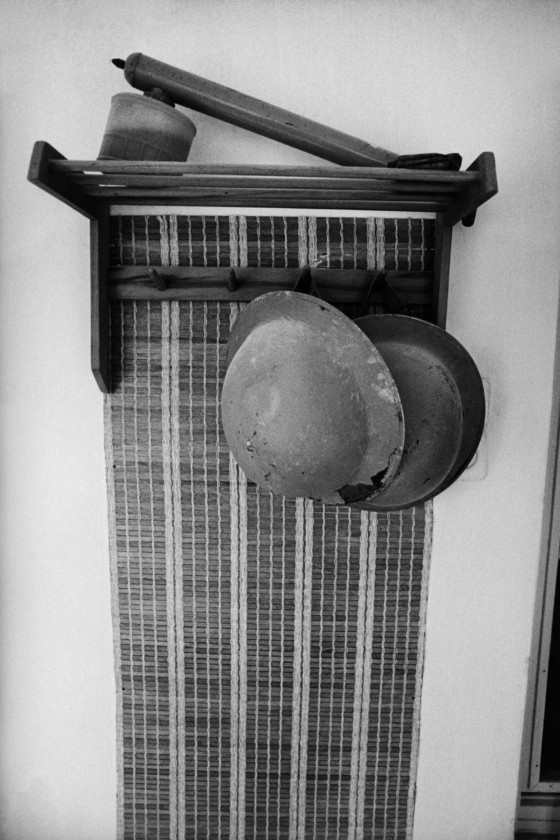

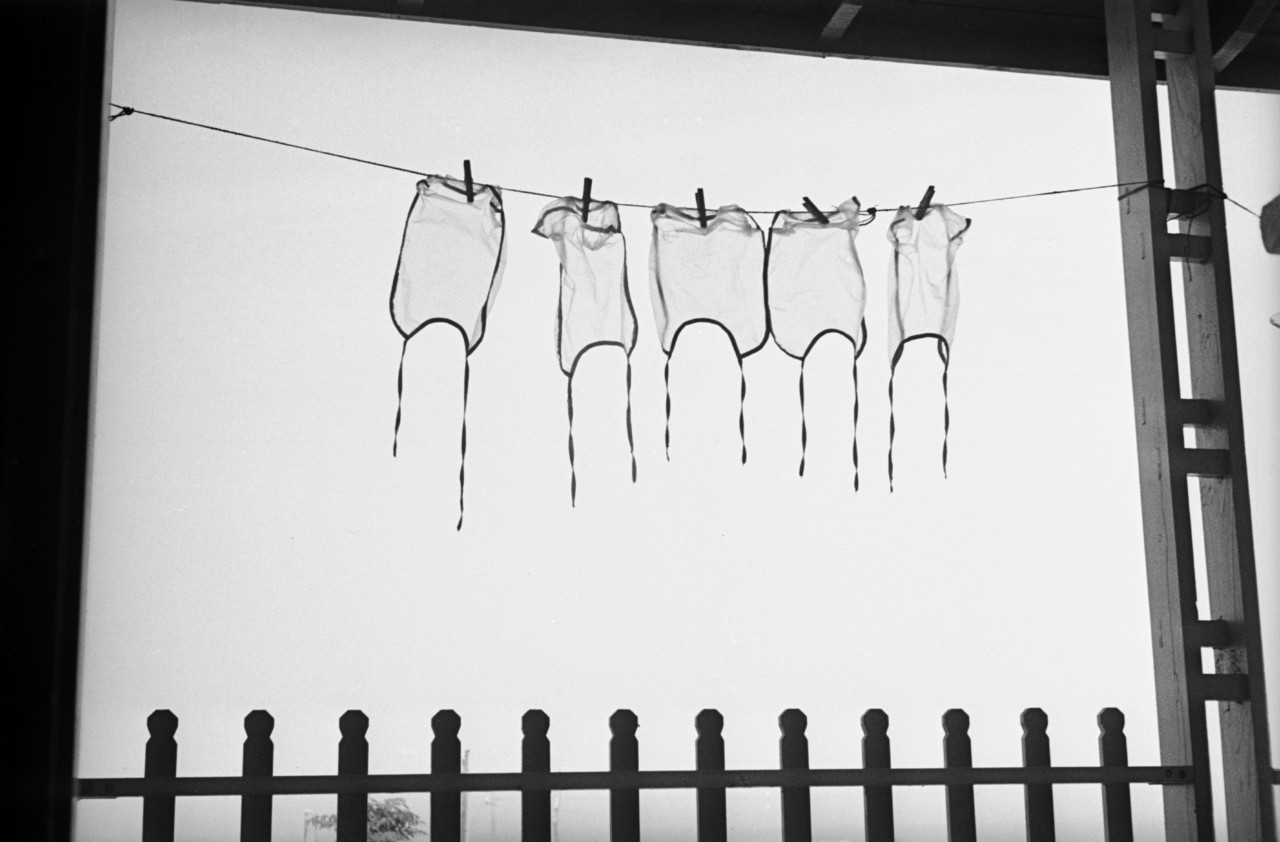

What was extinguished first, the fireflies or the kibbutz? The light in Micha Bar-Am’s photographs is not directed at the momentum, the produce, the crops, even though the majority of the photographs were taken in the kibbutz’s heyday. In the 1950s. The radiance in the photographs emanates from a different source. As if it were already a memory. A déjà-vu of the end: the open crack by the house; the children’s aprons hanging to dry; the empty beehives, reminiscent of little houses; the chairs upturned on the tables (before? after? certainly not during the event).

When I look at Bar-Am’s photographs, I always see, through the photographed subject, the end concealed in them; I see all the departures. Even though he left the kibbutz before I was born in 1960, I can see my own departure in them, too.