They Did Not Stop at Eboli

The recent rediscovery of a forgotten photo album expands upon David ‘Chim’ Seymour’s documentation of the battle against illiteracy in southern Italy

Recently, analysis of UNESCO’s audio-visual archives (prior to digitization) brought to light a forgotten photo album-cum-diary, kept by David ‘Chim’ Seymour, one of Magnum Photos’ founders. The rediscovered document was made in 1950, during his time documenting a UNSECO campaign against illiteracy in southern Italy. A number of Chim’s images from the project were published in 1952, in the UNESCO Courier – the organization’s in-house publication – alongside a text by Carlo Levi, by then famous for his memoir Christ Stopped at Eboli.

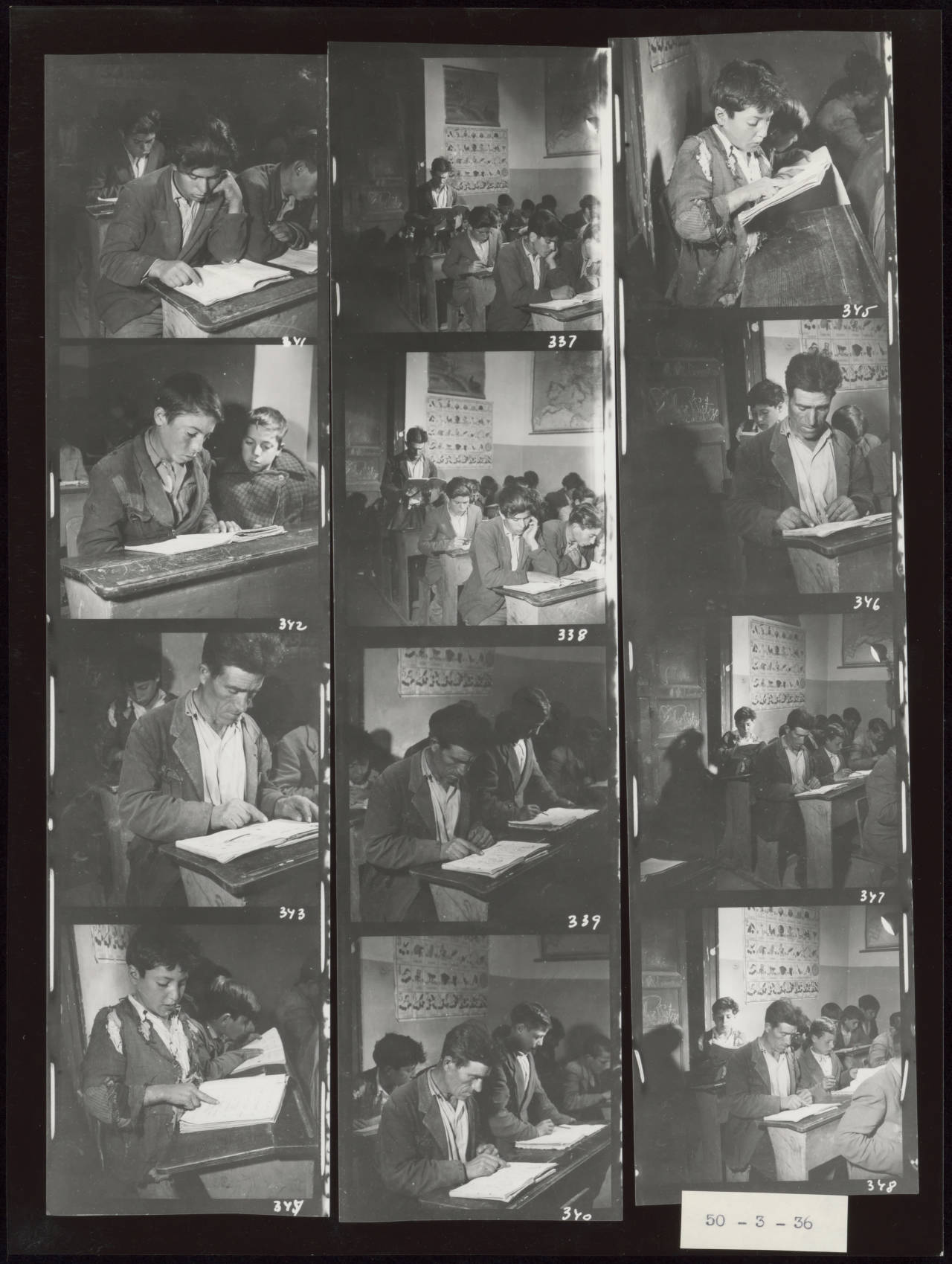

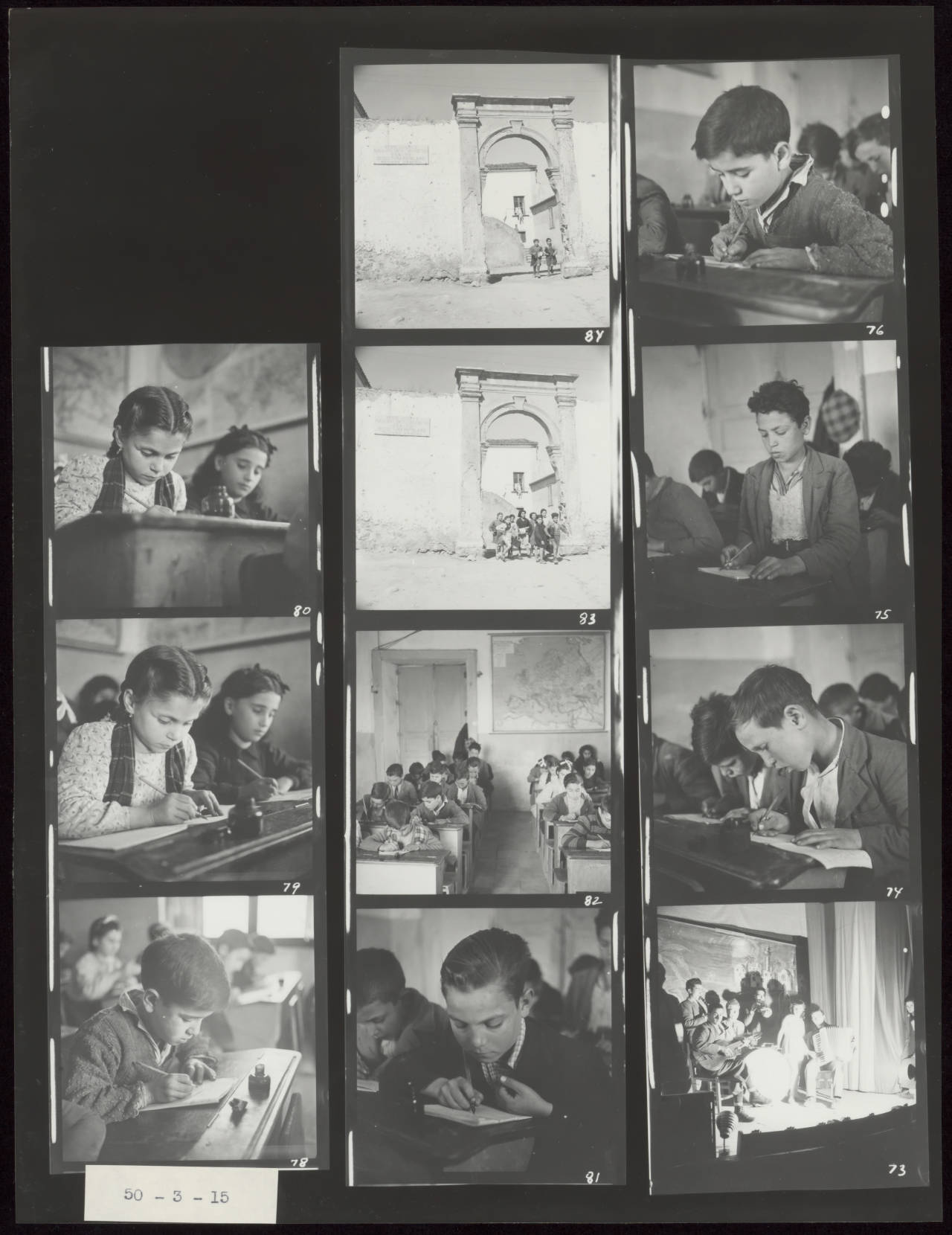

This rediscovery of previously unscrutinized photographs and notes offers important additions to Chim’s extensive documentation of post-war Europe, which included his Children of Europe project (arguably his best-known work), and spurred UNESCO and the editors of the DeGruyter book series Appearances. Studies in Visual Research to release a new book entitled They Did Not Stop at Eboli, drawing upon the new discoveries. The publication brings together 30 full-bleed photographs, contemporary press cuttings about the UNESCO campaign, contact sheets, and Chim’s previously unknown letters to Carlo Levi – as well as four new essays: on Chim’s photographs and their wider archival context at UNESCO (by Giovanna Hendel), on the image of Italian schools in the photographs of Italian photojournalism (by Juri Meda), on the intellectual friendship between Carlo Levi and Chim (by Carole Naggar) and on the rediscovered photography album as an editing tool and a means of storytelling (by Karin Priem).

Here, Carole Naggar writes about this newly discovered body of work, placing it in Seymour’s broader archive, reflecting on images and contact sheets from the forgotten album, as well as from number from his earlier and later works made in Post-War Europe.

The publication of They Did Not Stop at Eboli was supported by Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C2 DH) at the University of Luxembourg, as well as the Member State of Japan.

Full PDFs of the book are available for free download here, while hard copies are also available for purchase here.

“‘Here it is! It’s all written here,’ she said, pulling an already filled out ballot from her pocket, for all the world like a precious talisman. Alas, the old woman was illiterate, and someone had foisted a monarchical ballot upon her. When I explained the trick, she looked at me sorrowfully, and said: ‘Is that why they didn’t teach us to read?’”

Carlo Levi, “Italy Fights the Battle of Illiteracy” (1949)

A photographer’s archive is a living body: each time a discovery is made, the biographer’s – and the public’s – perspectives are enlightened and reshaped, both by the discovered material and by analysis of it. This is what happened with a recent discovery made in UNESCO’s archives in Paris.

Most of UNESCO’s audio-visual files, only recently transferred under the responsibility of the Archives Department, had barely been indexed since the organization was founded right after World War II, two years before Magnum Photos. The UNESCO archivists started to select material to be digitized, and by opening filing cabinets and drawers discovered a 38-page album with contact sheets, texts and captions by David ‘Chim’ Seymour: a 1950 report on illiteracy in southern Italy. Some of the images had been published in 1952 to illustrate an article in UNESCO’s magazine The UNESCO Courier with a text by Carlo Levi, the author brought to fame by his 1945 novel Christ Stopped at Eboli.

"Chim traveled to southern Italy on a UNESCO assignment to document illiteracy – a problem effecting as many as 35 percent of Italy’s rural population"

-

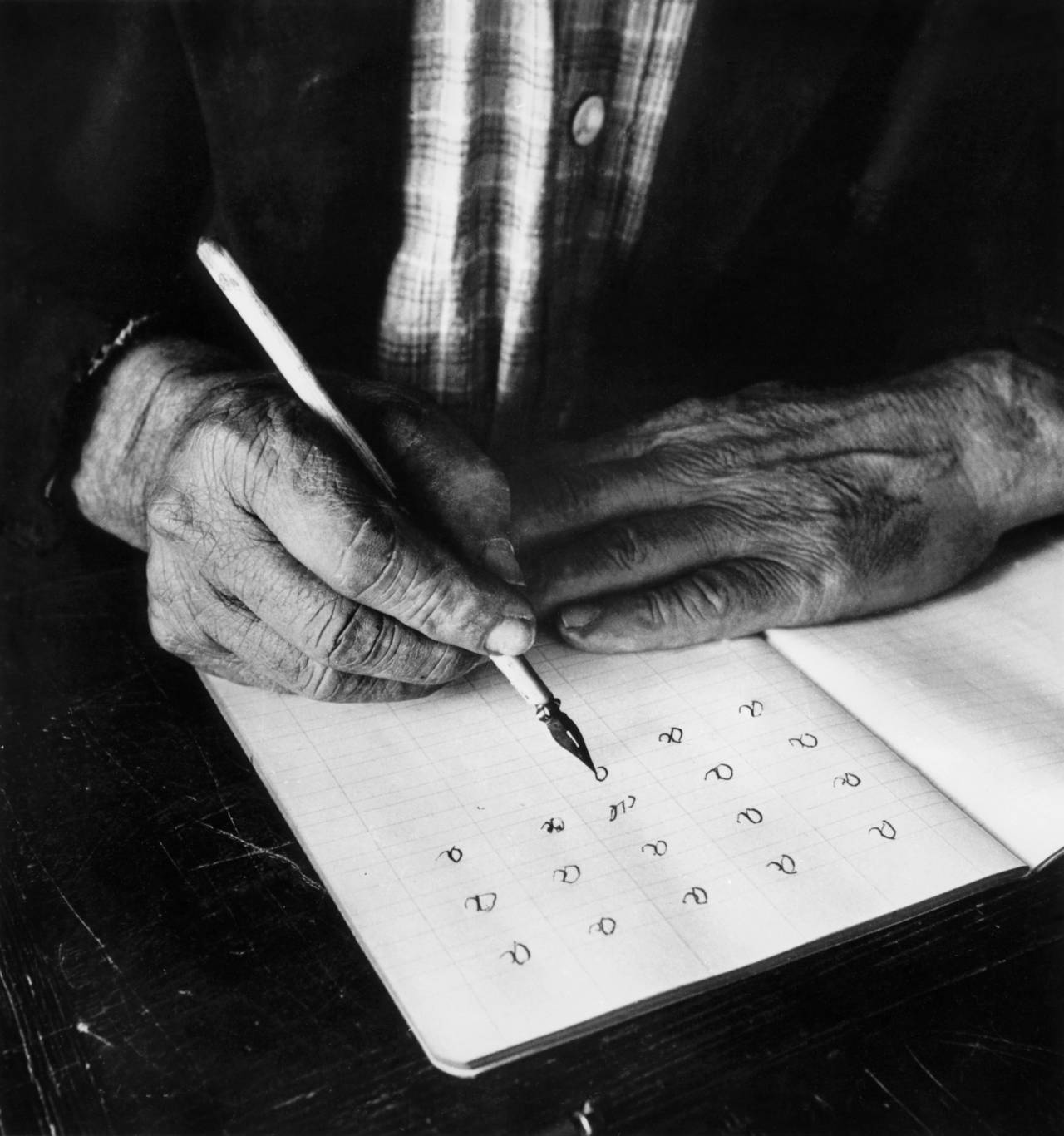

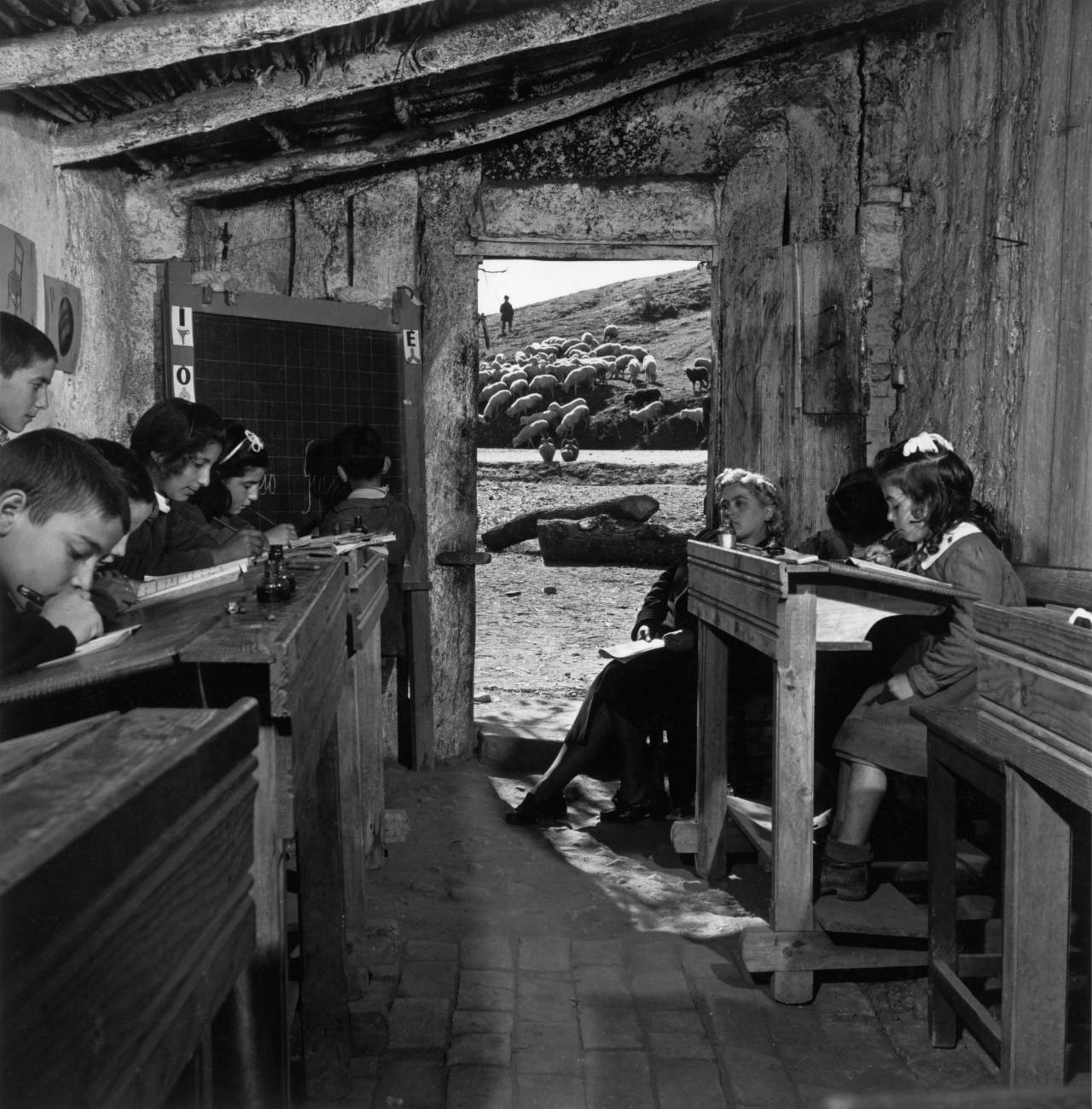

In the early spring of 1950, Chim traveled to southern Italy on a UNESCO assignment to document illiteracy – a problem effecting as many as 35 percent of Italy’s rural population. He photographed the new schools where peasants, the elderly and children alike, were taught to read and write by local volunteers and groups like the Unione Nazionale per la Lotta contro l’Analfabetismo, the National League for the struggle against illiteracy.

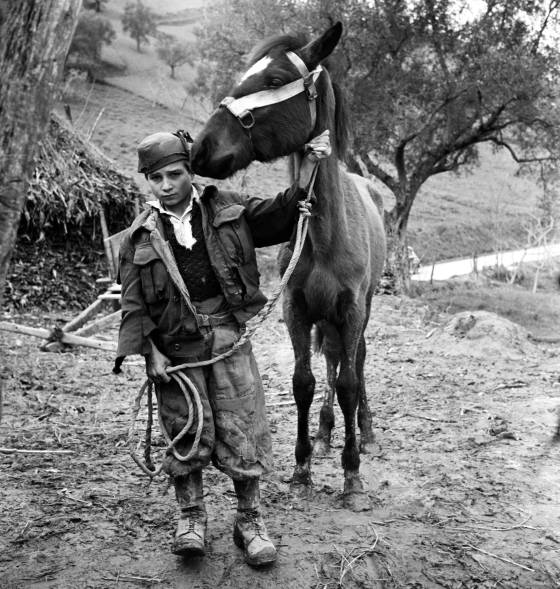

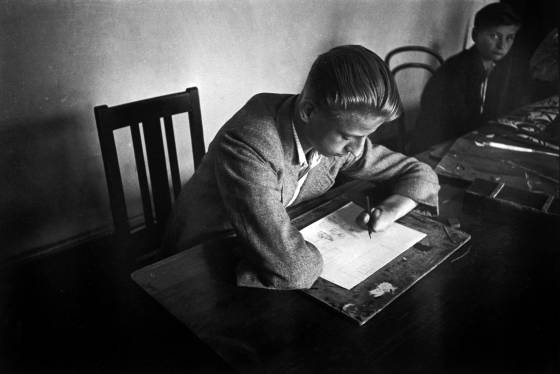

Chim had already traveled in the region in the summer of 1948, as part of a UNICEF–UNESCO assignment Children of Europe which saw him documenting the fate of displaced, orphaned, and maimed children in the wake of World War II. He photographed street children and orphans in Naples, then explored Basilicata, Bari, and the troglodyte village of Matera, shooting pictures of families that lived together with their animals in dark limestone cave dwellings. Because of that trip, he already knew about the poverty and isolation in southern Italy.

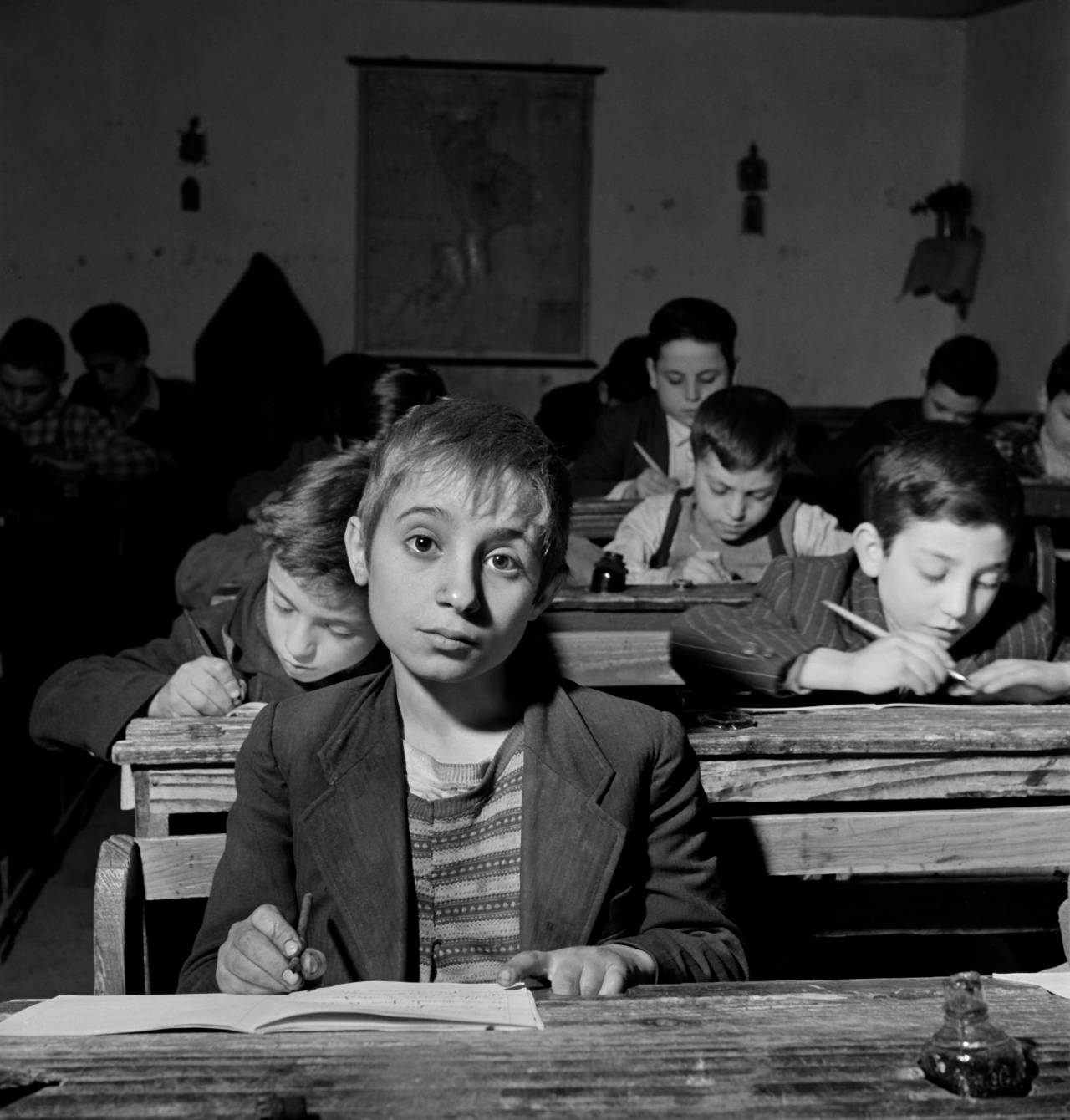

Chim’s photographs from the illiteracy project appear a direct continuation of his work on that earlier series. Looking at Chim’s 1950 images, I was amazed at the similarity of style and point of view to those in his photographs of children in 1948. The latter were victims of World War II, but Chim, when he visited schools in Austria, Greece, Hungary, Italy and Poland did not only show the children’s suffering, but their determination to find a new, meaningful life. He saw them hard at work, trying to catch up on the learning they had missed during the war years. As the son of a publisher of Yiddish and Hebrew books, reading and writing had always been central to Chim’s life, so that this choice of topic seems natural for him.

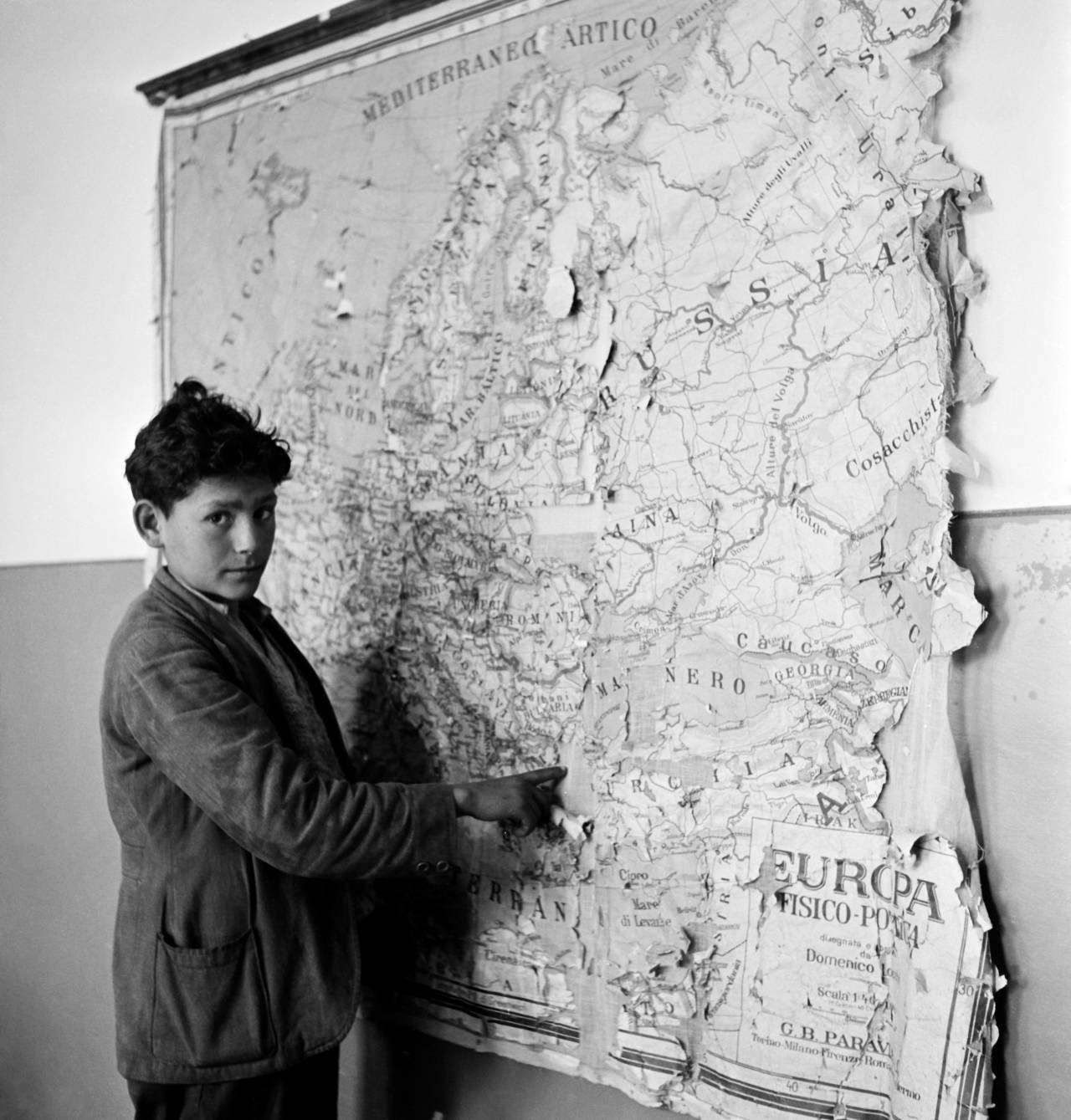

The children’s postures, hunched over their textbooks or notebooks or poring over maps, the paucity of learning materials, the improvised surroundings and furniture – child-sized tables, chairs, and benches – and the home-made classroom materials shown in his 1950 reportage all recall the 1948 photographs.

"The children’s postures, hunched over their textbooks or notebooks or poring over maps, the paucity of learning materials, the improvised surroundings and furniture... shown in his 1950 reportage all recall the 1948 photographs"

-

Chim thus suggests that the people of the Mezzogiorno were also oppressed victims of a war of sorts, waged not through weapons, but through politics, which had created the huge disparity between north and south. The people in southern Italy had been forgotten. They seemed to live in an enclave where time had stopped, while the rest of the country advanced in the period known as the “Italian economic miracle” in the 1950s and 1960s.

Chim’s reportage functions as a classic series, telling a story sequentially. But if we focus on individual pictures, it becomes a very different matter. Chim worked with close-ups inside peasants’ homes, old mills, disused barns, and cellars that served as classrooms. He used the poor lighting to create strong, dramatic, chiaroscuro effects. The individual photographs seem to expand into contemplative moments. It seems as if Chim, like Carlo Levi –when he had lived in southern Italy in political exile in 1935,interned as a Jew and a Communist– had been able to leave behind the accelerated rhythm of urban life and had started to share in the slow, almost immobile sense of time that was part of his subjects’ lives.

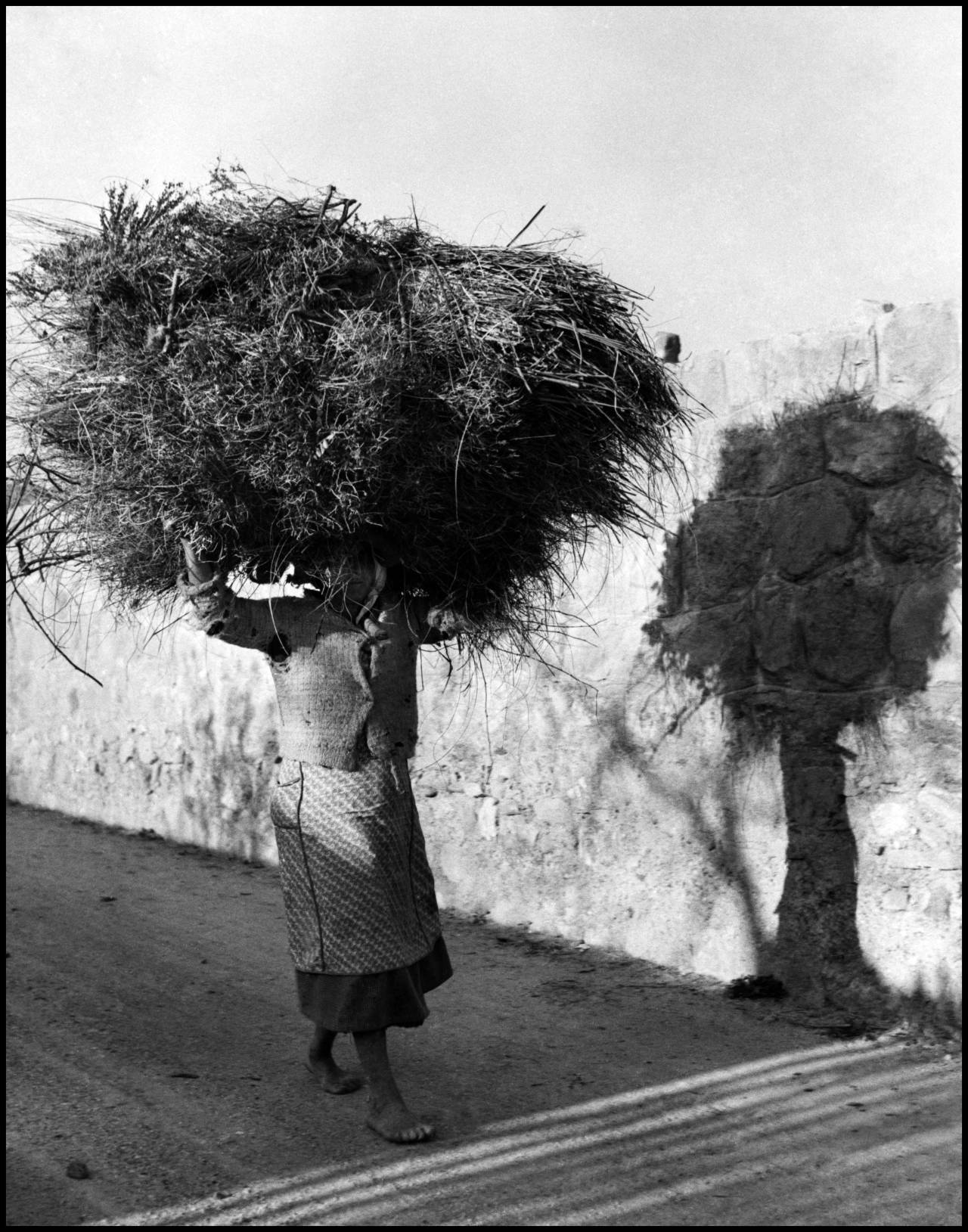

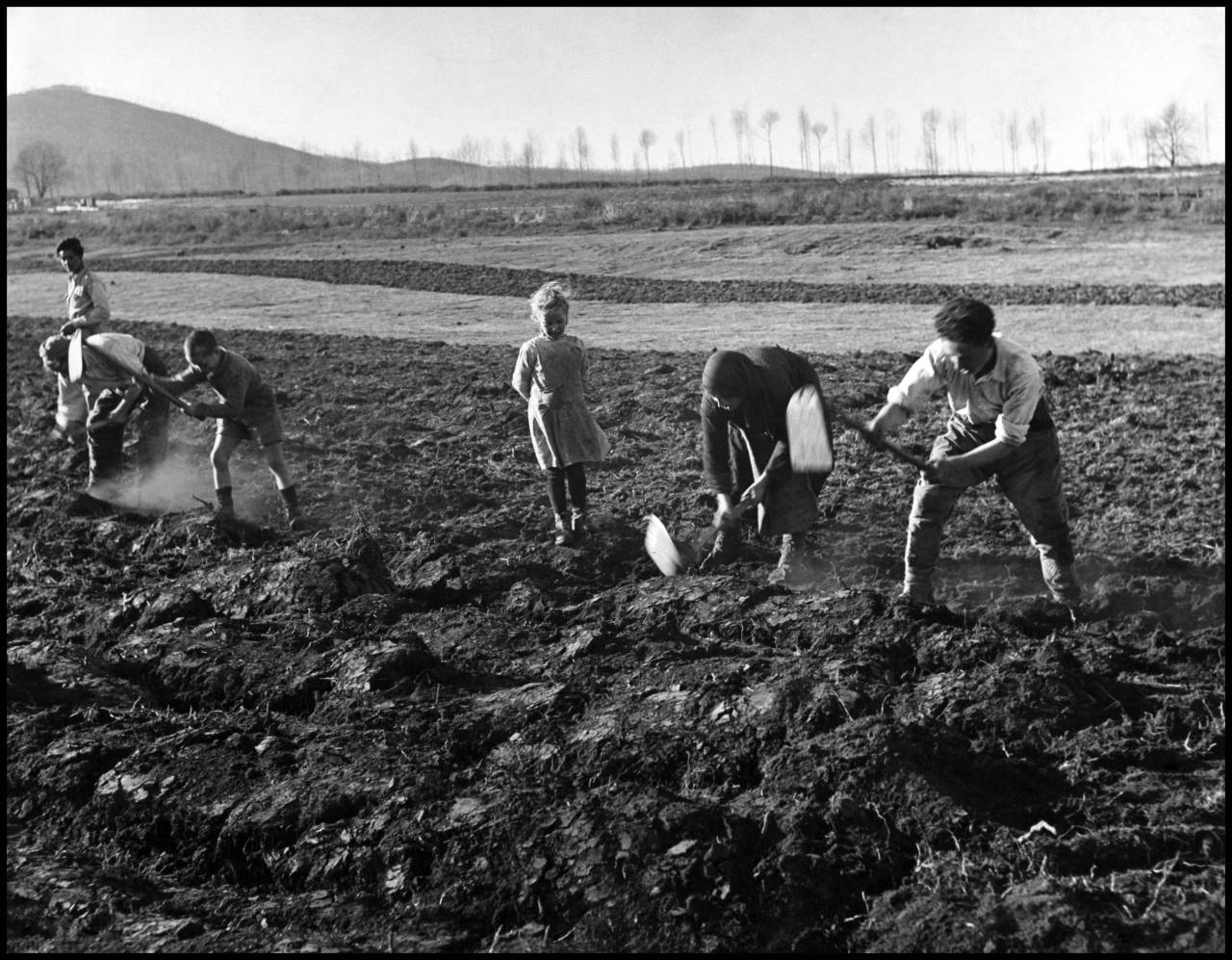

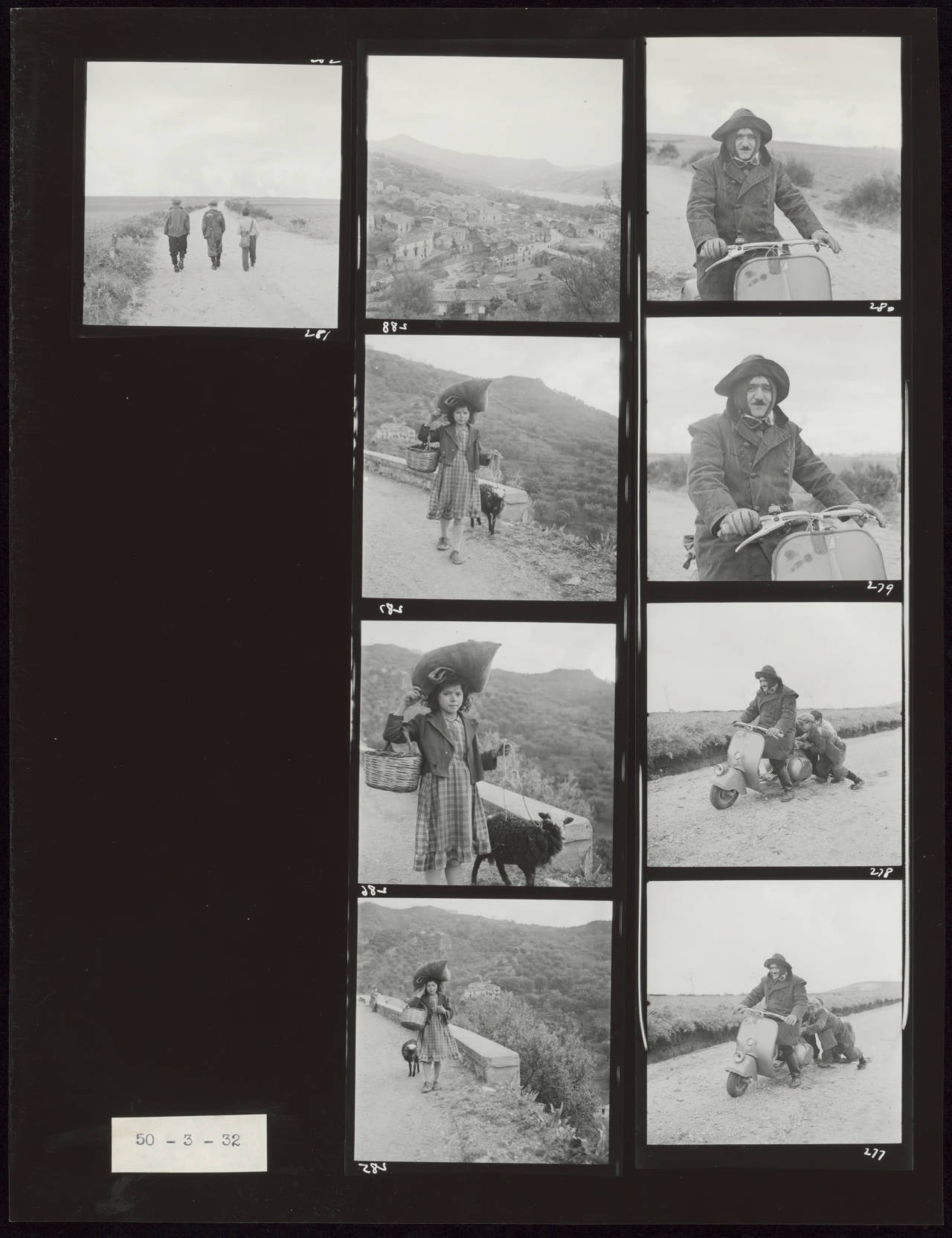

In his 1950 story, Chim did not limit himself to the mere fight against illiteracy: as he had done with the Children of Europe work, he went beyond the assignment, seeking to paint a broader picture of the peasants’ life. Exploring the streets, he took portraits of girls walking barefoot or in makeshift shoes along the village’s muddy paths, wrapped in wool shawls against the cold, sitting in a doorframe, doing homework; of women and even children carrying huge loads of furniture or firewood on their heads; of a young boy with his dog and a young shepherd; of a woman crowned with a nest of dried flowers or vegetables; of peasants occupying the land, the braccianti, and tilling the dry fields; of a village teacher on his motorcycle. He also expanded his view to include the unforgiving landscape of steep mountains and narrow, twisting paths and the barren fields dotted with few trees. It is a journey into nature, depicting the humble objects of everyday life, light, shadows, and animals, as if the photographer was traveling into the mind and consciousness of the people he photographed.

As well as the aforementioned echoes of his Children of Europe work, in Chim’s 1950 photographs – especially those images showing the land occupation by peasants – I also found striking echoes of his work during the Spanish Civil War: the land reform meetings, the peasants tilling the fields.

"While Fascist propaganda had used photography and words as tools to show the “New Italy,” these very weapons were turned around by Chim and Levi, employed to reveal the Italy that had been denied by Fascism: the poor, archaic Italy that did not trust - nor care about - governmental promises"

-

While fascist propaganda had used photography and words as tools to show the “New Italy,” these very weapons were turned around by Chim and Levi, employed to reveal the Italy that had been denied by fascism: the poor, archaic Italy that did not trust – nor care about – governmental promises. Poverty, hunger, the lack of access to land and education – the daily life of the peasants – are never shown in propaganda photographs.

Upon settling in Rome and choosing as a base the Hotel Inghilterra, at the heart of Rome’s power and social networks, Chim photographed the rising stars of Cinecittà – Hollywood before Hollywood – and saw the neorealist films by Rossellini, Fellini and others. In the illiteracy series his photographic style closely aligns with that of the post-war Italian neorealist photographers such as Enzo Sellerio, Mario de Biasi, Fulvio Roiter, Ando Gilardi,Aldo Beltrame, Arturo, Nino Migliori, Tino Petrelli… Foreign photographers, such as Paul Strand in his famous series Un Paese, also worked in that style and, like Chim, used a medium-format camera. Many others contributed to what has been called “lyrical realism”: Chim’s photographs definitely fall into that category.

"Chim’s work on illiteracy represents a pivotal moment. It serves both as a link to and continuation of Children of Europe and as an entry point to his later work on rituals"

-

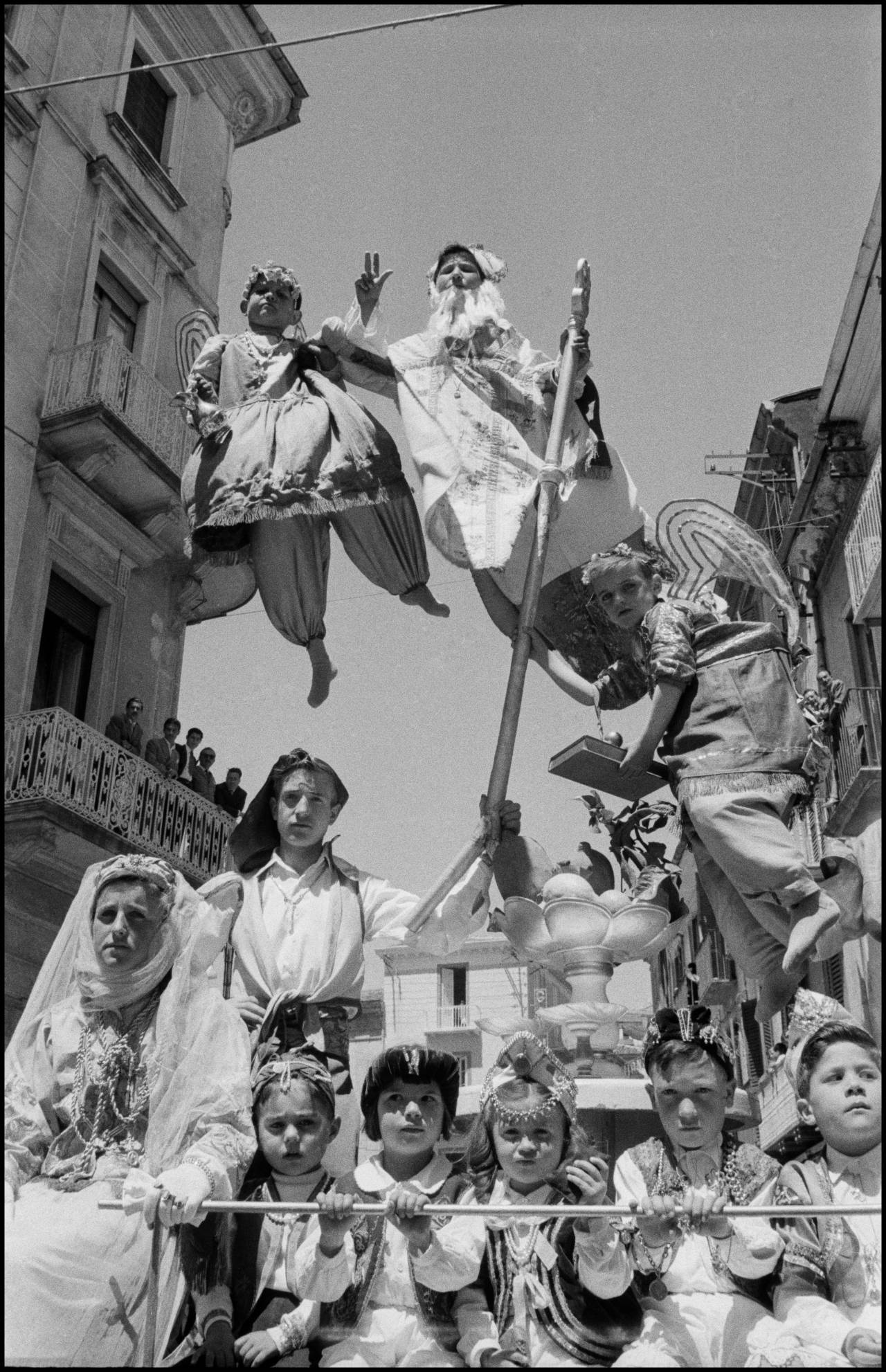

Chim’s work on illiteracy represents a pivotal moment. It serves both as a link to and continuation of Children of Europe and as an entry point to his later work on rituals. After he spent time exploring southern Italy and its distinctive oral culture, steeped in myths, animism and Catholic religion, Chim’s next few years (1951 to 1955) would see him traveling to remote villages of the South and documenting religious and pagan rituals and festivals in Sicily, the Basilicata and Calabria : the Holy Thursday procession in Caltanisseta, Sicily, the San Efisio procession in Cagliari, Sardinia, the Corpus Domini festival in Campobasso, Good Friday in San Fratelo…

Though an outsider, Chim managed to penetrate a civilization and a people that he did not belong to. He did not keep his distance but sought to be witness and protagonist at the same time. His photographs are not merely anthropological: they have a sense of depth and radiate poetry. They are deeply personal and imbued with empathy and emotion. All in all, in his work on the campaign against illiteracy, Chim created a lyrical portrait of a fragile society on the brink of change.