The Darker Side of Tourism

As part of his ongoing project, War Games, Thomas Dworzak explores the complex world of ‘dark tourism’

The concept of ‘dark tourism’, which can be loosely defined as a tourist site or experience that commemorates a tragic event, is nothing new. In medieval Britain, pilgrims flocked to Canterbury to the site where Thomas Becket was murdered, while Americans travelled to Gettysburg in 1863 to witness the aftermath of one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. Now, sites like the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin are visited by hundreds of thousands a year and the appeal of such places only seems to be expanding.

As part of his ongoing series, War Games, Thomas Dworzak examines this complex world in its various manifestations. He believes that an interest in visiting places associated with tragedy and death is simply human nature. “We have a general attraction to the morbid,” he says. “Why do people watch horror movies?” As part of the project—which is yet to be finished—he visited war memorials and museums, photographed a fake DMZ in Korea, observed re-enactments and interactive theatre performances. Though wildly different in their various purposes and execution, the common theme to be found in these sites is their ambiguous relationship with reality, and propriety.

"All of these sites are kind of on the border of poor taste"

- Thomas Dworzak

There are thousands of these types of sites all over the world and Dworzak chose which to visit “in a fairly random way.” He further explains, “I explored places a little bit like I did for the World War I [Postcards] project; I will go anywhere that I can afford to go,” he explains. “I have a long list of everywhere I want to go eventually; it’s not extremely methodical but the common thing is the elements of fakeness or recreation. I have dealt a lot with real conflict, so anything that is not real, in a way, qualifies.”

One of his strangest encounters in the making of this work was at the Museum of Drug Elimination in Myanmar, where life size dioramas depict the various chapters of drug addiction, according to the Burmese government. The series starts with a house party and ends in death. But rather than feeling sinister, the absurd and unintentionally comic displays—and the fact Dworzak was the only visitor on that day—made the museum feel “incredibly quaint”. “All of these [sites] are kind of on the border of poor taste,” says Dworzak. “It’s a very dangerous field. It comes with it; it is problematic if its very nationalistic but also if it’s very well intended.”

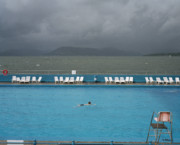

Other places Dworzak visited he found to be similarly off-key. At Auckland War Memorial Museum, a 2015 exhibition utilised the popular Minecraft game as a way to engage students with the events that occurred at Gallipoli in 1915. Meanwhile at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, in Moscow, he watched various reenactments of scenes from the Old Testament including the plague of locusts and the flood; “You’re sitting on chairs that start shaking and when you’re sitting in the flood they actually spray you with water, like a little spritz, and that represents the flood. Pretty quirky!”

Did any of this make him feel uncomfortable? “There are lots of things that make you uncomfortable,” counters Dworzak. “They kind of achieve their aim when they make you uncomfortable. When you analyse the however-many-years of war, maybe there is something that should make you feel uncomfortable. But it’s the wrong thing if it is an exploitation of that.”

"Looking at the effort of what [a government] wants to show is incredibly revealing"

- Thomas Dworzak

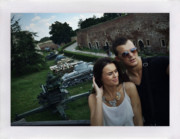

Beyond the textuality of the sites, Dworzak was concerned with the visitors’ interaction with them. “Of course there is a general code of conduct…an unspoken thing,” he says. “I can go to a concentration camp for example and it’s fairly sombre. Sure there’s some misbehavior, but generally people are referring to those codes when they go there. But when you look at it in the bigger picture, there might be a school trip of 16-year-olds, they’re having a lot of fun, there’s a lot of drinking, half of them fall in love, fall out of love or whatever…and all of this happens in the context of a concentration camp, I think that’s where it gets really interesting.”

By photographing these places, Dworzak hopes to peel back the layers of reality and unreality, fact and fantasy. But the question is not only who is attending these sites—and how are they behaving—but who is commissioning these exhibitions, paying for these displays or museums, and why. The approach taken in many of these ‘dark tourism’ sites is revealing of the preferred historical narrative that a government decides to commemorate. “I’m not taking it at face value,” says Dworzak. “But looking at what [a government] wants to show you is incredibly revealing. It’s like looking at state TV; it shows what they want to tell you, the message they want to get out.”

Explore more stories on how society holidays on Magnum here.