The Seventh Wave

Trent Parke’s deep dive into the Australian psyche takes us under water and into mankind’s relationship with nature

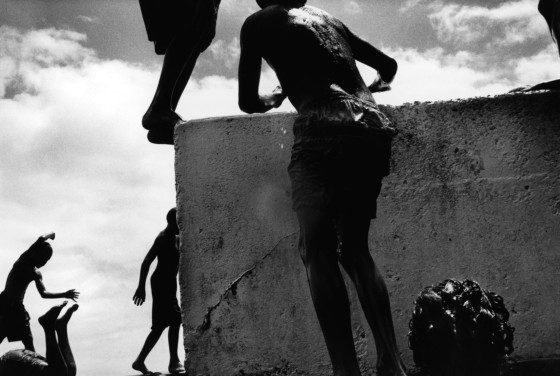

Trent Parke and Narelle Autio, who would later become Parke’s wife, were drawn to document Australian Beach life in early 1999, during one of the country’s worst summers for drownings. In a project that spanned two years, and beaches from Bondi in Sydney to Freshwater and Manly beaches, north to Newcastle’s Bogie Hole, to Port Macquarie and Byron Bay, the pair’s underwater shots built a portrait of an Australian past-time that captured something of the national identity, as well as something broader and universal about humanity’s relationship to wild nature.

“The ocean is a symbol for the ultimate universal energy — something which both gives and takes away life,” says Narelle Autio. “It can be tranquil and calm or violent and unpredictable. Despite the dangers and inevitable loss of life the sea continues to be an irresistible attraction to millions of people. We wanted to show this symbiosis between mankind and the ocean and our apparent ongoing need to return to water.”

Here, Trent Parke recalls working on a project, where a perceived mistake led to photographs that were a perfect expression of what the pair experienced.

Three photographs from The Seventh Wave are now available to purchase as Magnum Editions Posters and Contact Sheets as part of the Summertide Collection in the Magnum Shop. Shop the collection online here.

Twenty years ago, this was the first major body of work Narelle and I made together. It was soon after we first met.

Even though we grew up on opposite sides of the country we both lived near the beach and like for most Australians, the beach played a major role in our childhood.

Narelle had just returned from Europe where she had spent several years working as a photojournalist and I had just completed several summers on tour with the Australian cricket team as a sports photographer. It had been a demanding time for both of us and this work allowed us to free ourselves from the constraints of long lenses, concrete stadiums and newspaper formula. It was the first time either of us had worked together and because we had the same ideas about photography it was an easy collaboration. Photography is usually so isolating; this was the opposite—it brought us together.

"Photography is usually so isolating; this was the opposite—it brought us together

"

- Trent Parke

Our life provided the inspiration: summer is hot in Australia and you don’t want to be anywhere else but the beach on a hot day. In those early years together we never put a camera down so it was an extension of the way we were living to keep photographing. Like with all our work, we always try to find a way of showing something familiar in a completely different light… And with this work, we set ourselves one rule. We had to have at least one foot in the water while shooting, so we bought one small 35 mm underwater Nikonos, a couple of lenses, and literally started the next day.

We spent every available moment shooting: weekends, after work, anytime we had. We studied the weather patterns, learned which beaches had the clearest waters, the most swimmers and started a two-year investigation of the East Coast beaches and the way Australians interact with it.

We shot it all on a breath of air and in a way–it was the ultimate candid photography. No one even knew we were there as they battled to swim, surf and survive the waves. We had no idea exactly what we were getting either as it was almost impossible to frame anything up. We would thrust the camera at arms length out in front and shoot a single frame, maybe two if we could stay down long enough, before being tossed head over heels by the power of the ocean.

At the end of each day we would eagerly hand-process the negs, full of excitement and apprehension. We never really knew until pulling those negs out of the tank whether what we had seen was as good as we thought it would be, or if we had actually managed to capture the moment at all. There was also a lot of friendly rivalry, a competition to find out who had had the most successful day. Spurring each other on with our various triumphs and failures.

At first we would take turns shooting a single roll as it was incredibly tiring work, diving under large waves, churning white wash, undercurrents, rips and cold temperatures. It wasn’t long before we bought another Nikonos and then we were both out in the water, Narelle was able to hold her breath for an amazing amount of time and we always found ourselves pushing our last remaining breath to the limits, knowing we only ever had a limited time before our lungs forced us to surface–and that unique moment would be lost forever.

"We always found ourselves pushing our last remaining breath to the limits"

- Trent Parke

Photographing at the mercy of the ocean meant we had to go with it. Sometimes we were sideways, upside down, and very rarely in control. We would be battling large waves swimming one handed with the camera strapped around the wrist on the other.

It took maybe a month of experimenting and testing before we eventually worked out how to get the results we were after. At first, we let the camera decide the exposure, such was the inconsistency of light under the waves. However, this led to many blurry abstract images as the camera would choose low shutter speeds. The images were interesting in their own right but it was not what we could see or wanted.

As is often the case it took an accident to help unlock the way forward.

Conditions for underwater photography had to be exactly right. Good visibility, which meant clear water, no rain and runoff for the days previous, the right currents, hot temperatures to draw out the crowds, and the right surf conditions. The bigger the waves the better, and the red and yellow swimming safety flags had to be as close as possible to keep the swimmers corralled in a small area.

It was the end of a long day. We had been in the water the whole time, taking turns using the camera and had shot around 6 to 7 rolls each. I suddenly realized that the light meter was not working. We had been wearing dive masks for the whole day and neither of us had noticed.

Panic.

I realized I had put the battery in upside down at the start of the day and as a result the camera had only fired on this one single high shutter speed–all the days shoot was completely underexposed.

I was furious that I had made such a mistake and after relaying this to Narelle back on the beach her response was not to worry and that things happen for a reason.

"We shot it all on a breath of air

"

- Trent Parke

We decided to take a chance with the processing. We used a concentrated amount of developer and push processed the film for an enormous amount of time. Almost long enough to strip the emulsion from the film itself and we doubted there would even be any images left.

To our amazement when we pulled the first reel from the stainless steel tank, the negatives looked perfect. Exactly what we had been seeing but not able to capture. Everything came together, the high shutter speed had captured the movement of both the swimmers and the ocean with a sharp clarity, the grain had a three-dimensional feel and the emulsion seemed enhanced in some way, it had a mercurial quality–like liquid silver.

From that point on we shot everything the same way.

Published as part of Magnum’s summer series of stories: ‘Life by the Sea: Exploring identity through society at leisure and the pursuit of pleasure.’ See the rest of the stories from the series here.