Tar Beach

Susan Meiselas' new book charts a photographic history and tradition unique to New York's Little Italy

Susan Meiselas has lived in the portion of Manhattan known as Little Italy since 1974, and made some of her most famous images and projects on the neighborhood’s streets. But, as she writes in the introduction to her new book, Tar Beach, she “never even imagined what had been happening on the rooftops surrounding me.”

The photographic phenomenon Meiselas refers to, and which the book charts and exposes to outside eyes, is that of Little Italy’s familial home photographs, shot on the tar-painted roofs of the area. These “candid yet formal” images leapt out to Meiselas as she reviewed the community’s vernacular photographic history as part of the Mott Street Memory Project in 2015.

Since then Meiselas, along with Virginia Bynum and Angel Marinaccio, have worked to collect these pictures and the anecdotes, memories and tales that go with them. Like her Kurdistan project and book, Tar Beach is an archival work, a collection of memories and faces charting a changing city and neighbourhood, where the photographers themselves are largely unknown and unseen.

As Martin Scorsese writes in the book’s introduction, the roofs of Little Italy, and indeed much of New York city occupy an outsized place in the imagination and lives of its residents, “The roof was our escape hatch and it was our sanctuary…”

Below, photographer and writer Sumeja Tulic reflects on these images, the nature of New York, and of the hidden world of ‘tar beach’.

Signed copies of Tar Beach are available now on the Magnum Shop.

One remembers the meaning of terms by their examples. Here is one. Clustered lights curbing the night’s invincible darkness, reflected in waters called rivers, dispatched by the eyes, airlifted by the heart. It’s not New York; it’s not Manhattan; it is not the city. It’s an image of a place seen before. A place made inaccessible by time, distance, or perspective. A place one looks at and irrationally tries to carve a space in. It is what one makes of another’s desires. Desiring (a person, an object, or an outcome) creates bondage with life, and the outward projections of such desires, as structures and images, also binds people together—often, in cities. While Paris is a city of phantasmagorias, and Berlin is a palimpsest, New York is composed of simulacrums. Tar Beach. Life on the Rooftops of Little Italy, a book by Susan Meiselas, is a collection of one of the many intimate simulacrums that preserve, reflect, and emulate the lived and imagined realities of New York.

Unknowingly, Meiselas began working on the book in one of Little Italy’s last Social Clubs, Cafetal, where current and past residents met in 2015 to discuss ways to commemorate the bicentennial of the Basilica of St Patrick Old Church, the neighborhood’s most prominent landmark. Their aim was to enrich the celebration with visual representations of the neighborhood’s Italian, immigrant, and working-class history as photographed inside and outside the church’s walls. From the many photographs collected, what stood out to Meiselas, a long time resident of Little Italy, were the few depicting a place unbeknown to her.

“You’re away from everybody… in a world of make believe,” writes Angel Marinaccio, one of the two principal collaborators on the project, in one of the reflections accompanying the book’s selection of rooftop photographs from 1940 to the early 1970s. All the photographs have been taken on the tar-coated rooftops of tenement and apartment houses. “To me the roof was a blank canvas. It was like an artist studio,” writes Virginia Bynum, the second collaborator on the book, adding, “It was one of the only places in the neighborhood where you could take a proper photograph.” To understand what constitutes a proper ‘tar beach’ photograph, one needs to understand the ritual.

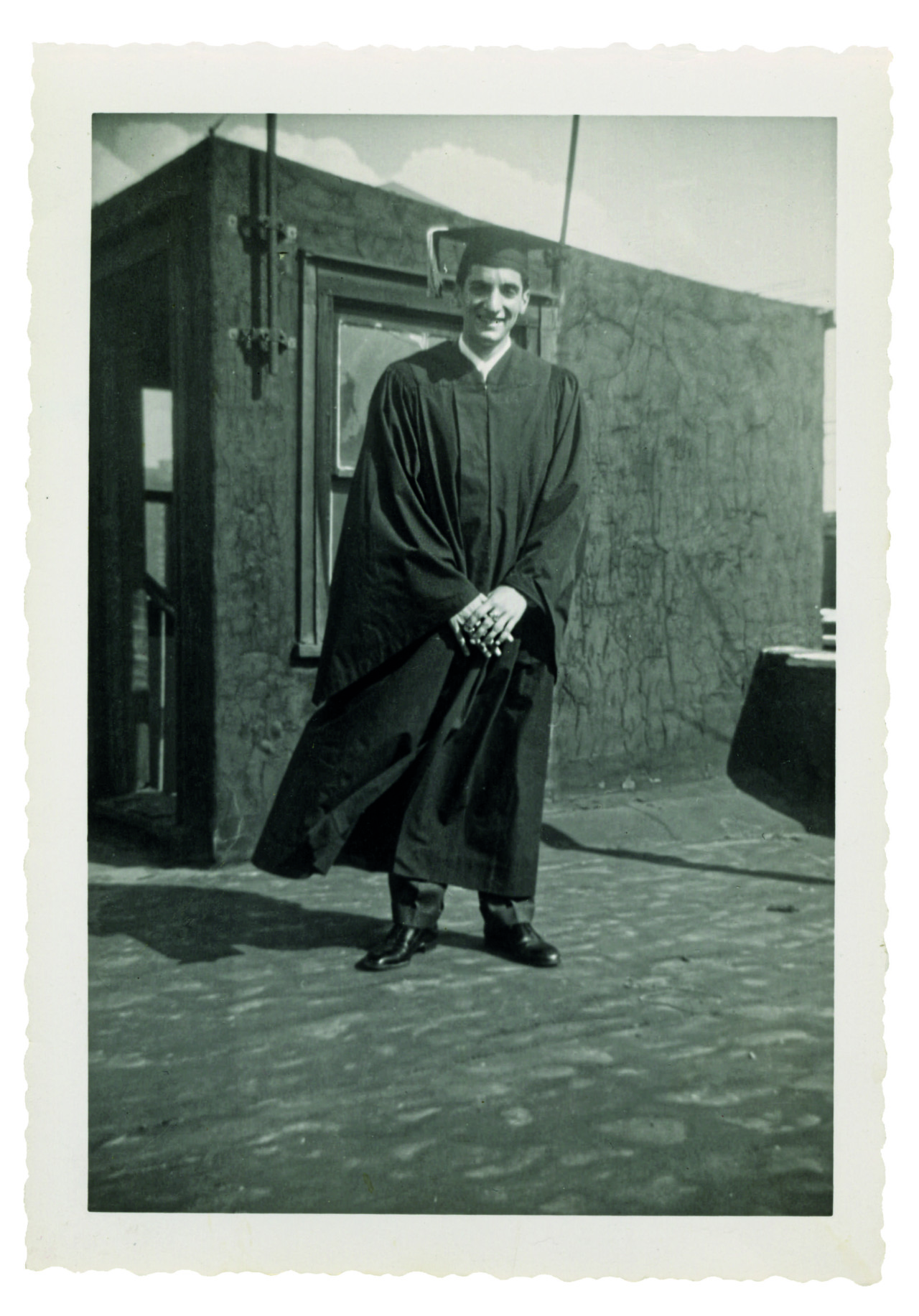

"If you had an accomplishment—communion, confirmation, wedding, graduation or birthday, you'd dress up in your best outfit and go to the rooftop to take pictures and celebrate with your family"

- Angel Marinaccio

“If you had an accomplishment—communion, confirmation, wedding, graduation or birthday, you’d dress up in your best outfit and go to the rooftop to take pictures and celebrate with your family,” writes Marinaccio. The ritual’s rationale is tucked closer to the end of the book, left off of a black and white image of a woman. The shadow cast by her fancy hat obscures half of her face, but not her smile. She stands tall and pretty, between the aerial city in her back and the shadows of two people falling before her long gown. In the photo index at the back of the book, it says that the woman is Edith Perrota, in her 20s, photographed the day of her friend’s wedding, at the offset of the Great Depression, in the late 1930s.

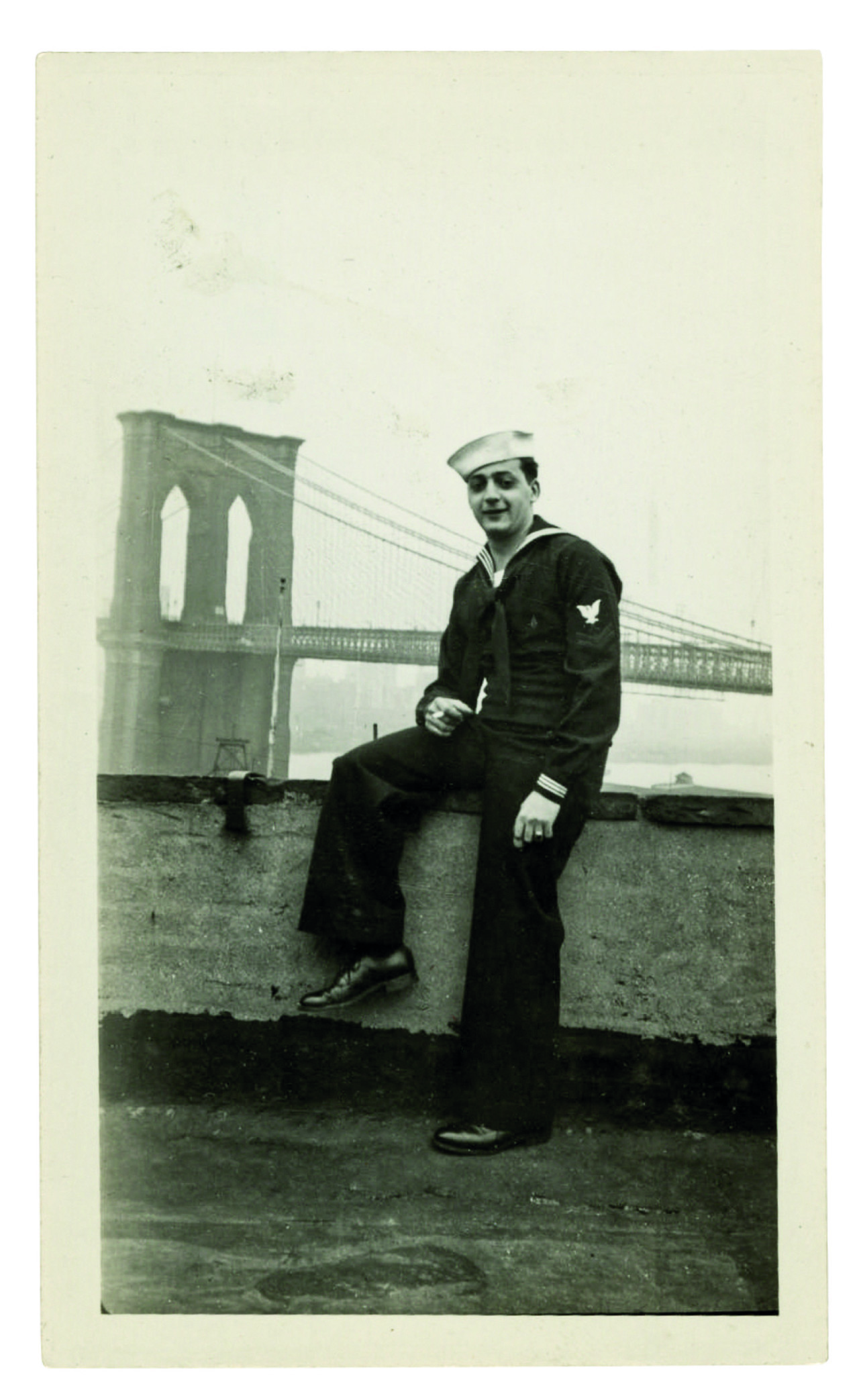

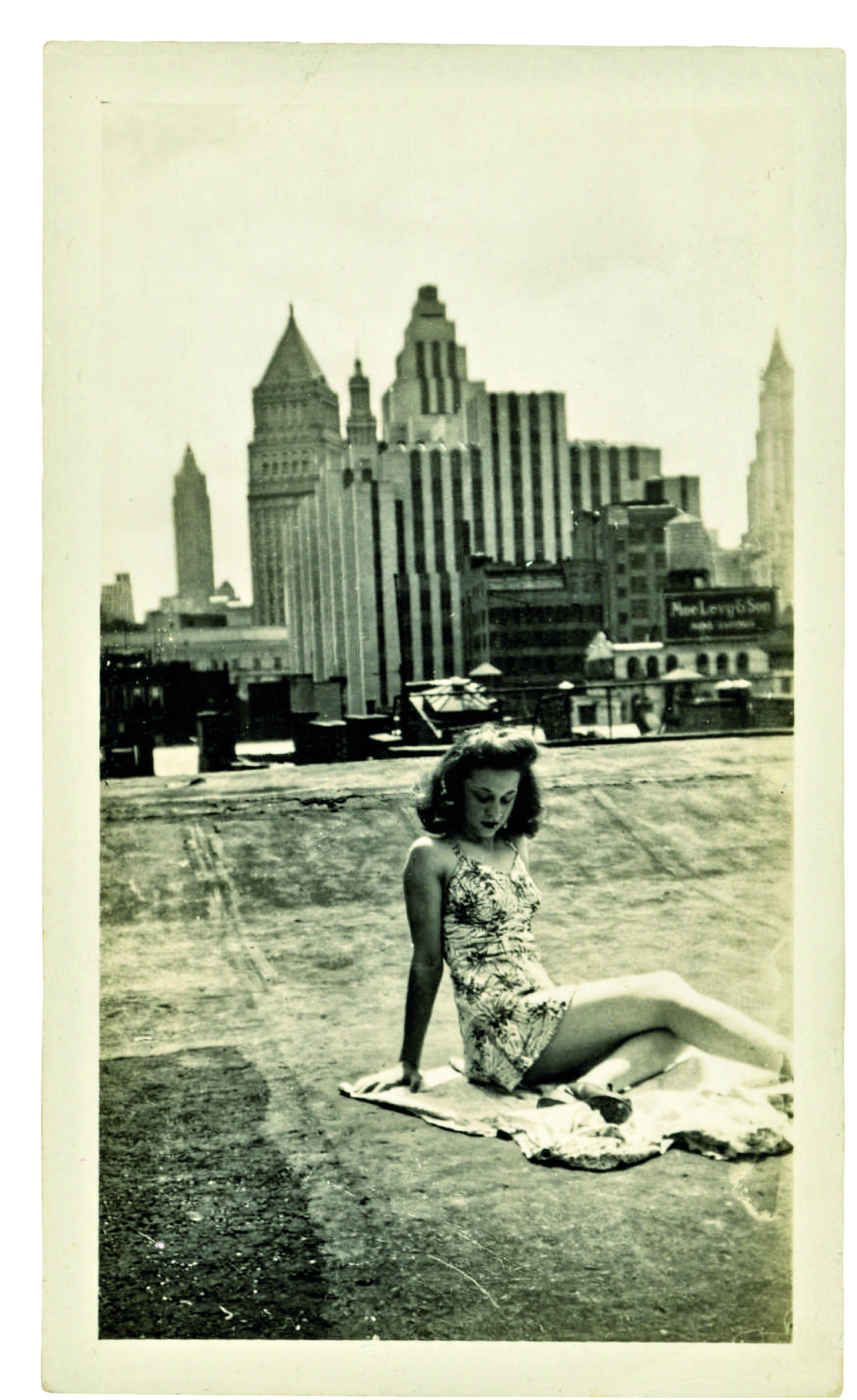

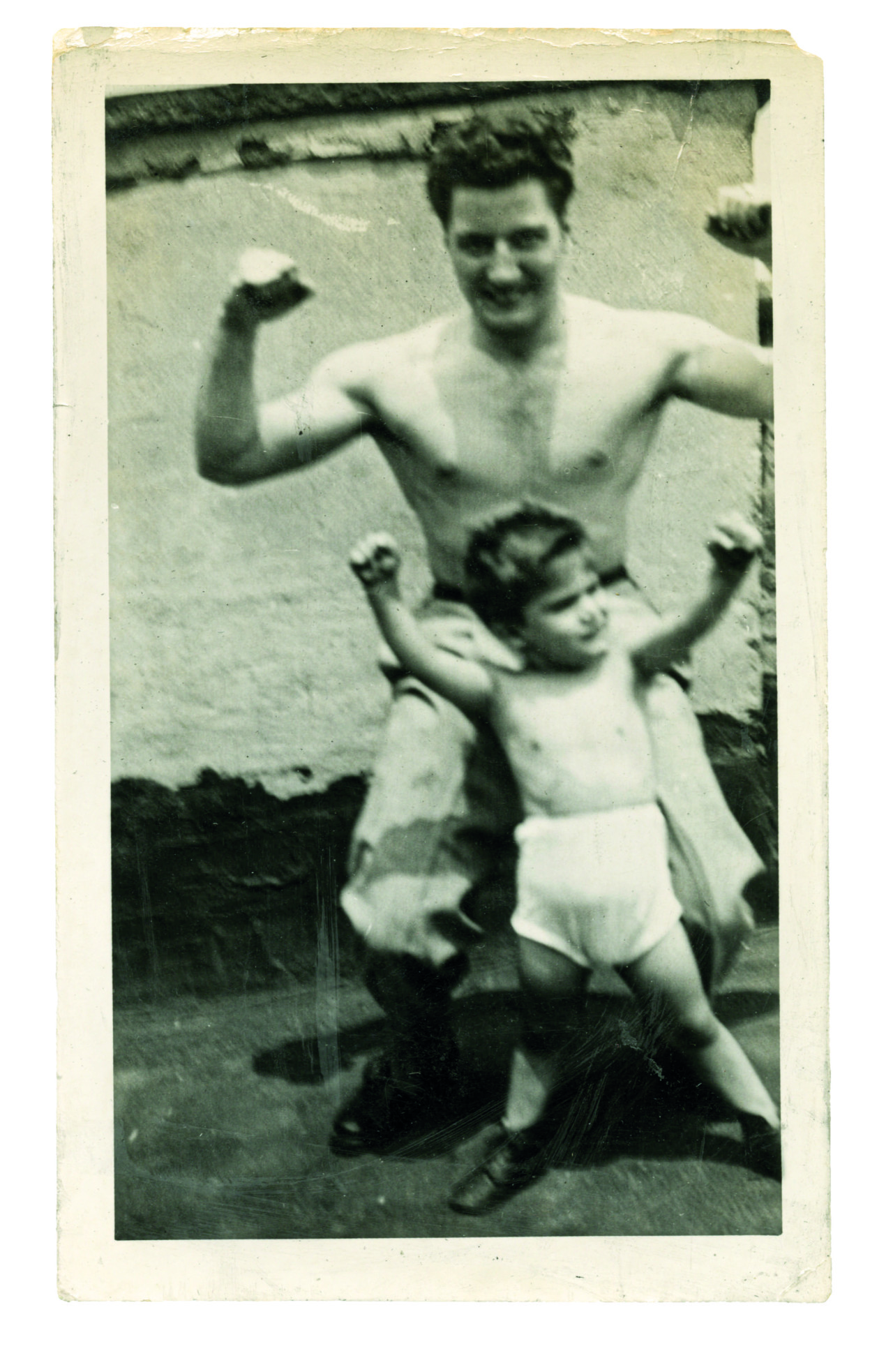

In flipping the book’s pages, the spectrum of life reveals itself as different occasions represented by graduation gowns, christening dresses, skimpy summer wear, and morning outfits. Aside from the sartorial choices, the photographs range in color and kind, from sepia, black and white, to full color with that all-too-known ’70s hue. Regardless of the occasion and tone, the subjects in the photographs are uniformly comfortable and present. “Families and friends face the camera with trust, expressing their pleasure of presenting themselves to be seen,” writes Meiselas in the preface of the book.

""No one remembers who the person in the family was with the camera--and there is no one left to ask," explains Bynum. Still, he or she is a trusted kin, before whom women are playful, seductive, beautiful, and strong, and men, as in most photographs, prideful and stunned"

-

Two factors made the people in the photographs comfortable and willing to be seen: space and the photographer. The photographer who captured these moments of pride, pleasure, and presence is invisible in the photographs and unknown to those preserving his/her work. “No one remembers who the person in the family was with the camera–and there is no one left to ask,” explains Bynum. Still, he or she is trusted kin, before whom women are playful, seductive, beautiful, and strong, and men, as in most photographs, prideful and stunned.

In his introduction to the book, Martin Scorsese enumerates reasons that made the roof an adequate place to commemorate all matters of significance to one’s life that occurred or have been achieved down the stairs. “The roof was our escape hatch and it was our sanctuary. The endless crowds, the filth and the grime, the constant noise, the chaos, the claustrophobia, the non-stop motion of everything… you would walk up that flight of stairs, open the door, and you were above it all. You could breathe. You could dream. You could be”

"Within Tar Beach, the habitual escape from the ground levels to the open-air stratum of one's home and life to be photographed, blossoms into profoundly touching representations of intimate realities"

-

Within Tar Beach, the habitual escape from the ground levels to the open-air stratum of one’s home and life to be photographed, blossoms into profoundly touching representations of intimate realities. One of its possible premises is that the immigrant and working class’s accomplishments are dwarfed by the city’s skyscrapers and made incomprehensible by the commotion and bustle on the street level. To perform significance, these accomplishments and their agents needed to dislocate from their spatial reality and descend to a place where what renders them insignificant is no longer. On the rooftop, the skyscrapers blend into a backdrop—a pale panoramic layer behind a subject standing in for a photograph. If anything, the backdrop serves to confirm the subject’s location, probably inscribed on the back of the photograph.

As Meiselas and her team of collaborators were finishing the book in the Spring of 2020, the video vignettes of New York rooftops were slowly taking over the Instagram flow. Although mostly filmed in Brooklyn, miles away from Little Italy, in looking at the people in these vignettes, one could have captioned them with Scorsese’s words, “You [can] breathe. You [can] dream. You [can] be.” They looked safe and secured from the dangers and inhibitions of public spaces. One envied them; one wanted to have what they had; one imagined oneself in their place. A presence signifying that in desiring an outcome, one has survived, “here of all places,” and as a proof, here is a photograph.