The Decisive Network

Photo historian Nadya Bair sheds light on the integral role Magnum's women played —as sales agents, writers, editors — in constructing the position of the agency in postwar visual culture

In her new book, The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market, photo historian Nadya Bair delves into the history of the Magnum agency, shedding unprecedented light upon the crucial role played by a network of staff – predominantly women – in making “photojournalism integral to postwar visual culture.” Here, to mark the book’s release, Bair introduces some of that history, highlighting the roles that Magnum staffers – sales agents, writers, editors and others – played in creating a new type of editorial photographic entity and market. Looking at the groundbreaking business practices of these women alongside the work of Magnum’s founders and early photographer members reveals the truly collaborative nature of photojournalism in the postwar world.

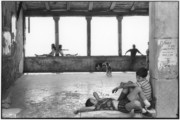

One of the few anonymous photographs in Magnum’s picture archive (above) was taken at what looks like a raucous party just days after the Liberation of Paris in August 1944.

The room is packed with the day’s leading photographers, magazine editors, and writers. Behind the already famous Robert Capa stands John Morris, then an editor in Life’s London office. To Capa’s left stand David (“Chim”) Seymour – with open collar – and Henri Cartier-Bresson – in a tweed jacket. Holding glasses of champagne and putting their arms around each other, the photographers and editors huddled close and smiled for the camera. The war was on its way to being over, and they were elated.

But within days, their celebrations were overshadowed by concerns about their future, and the post-war landscape for press photography.

What I discovered amounts to a new history of what it meant to shoot, edit, and sell news images after the war. I was already familiar with Magnum’s work when I started this project, nearly a decade ago as a doctoral dissertation at the University of Southern California. But I was also determined to look beyond Magnum’s iconic pictures and the legendary stories about its founders and members in order to ask new questions about the organization. What were the unique technological, cultural, and economic demands of photojournalism that Magnum navigated in the aftermath of World War II? How did Magnum actually run, day-to-day, in New York and in Paris? And what could its archives – not just its photographs, but its internal memos, letters, and other correspondence between photographers, staff and editors – tell us about picture distribution in the postwar decades?

To reconstruct Magnum’s early history, I traveled to public archives, private foundations and photographer estates across the U.S. and Europe. I contacted the people who had worked at Magnum early on or were married to photographers and had documents in their basements and attics. And I dove into the archives of magazines such as Life, Holiday, and National Geographic, and corporations such as Standard Oil and Pillsbury, all of which employed Magnum photographers in the 1940s and 1950s. Magnum was certainly integral to the history of postwar photojournalism, but no more so than the magazines and corporations with which it worked.

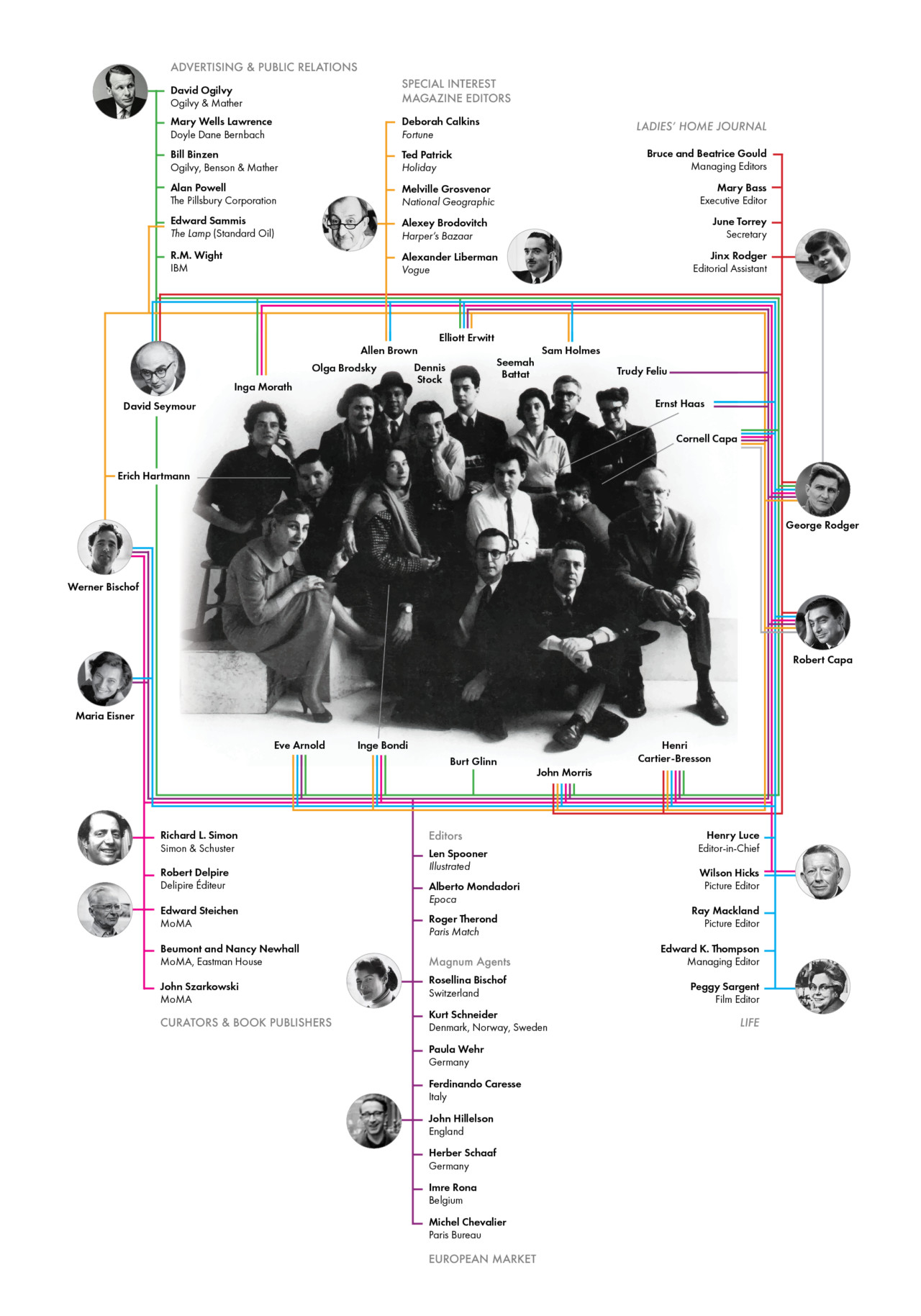

One thing became clear: Magnum’s photographers could not have done any of it alone. The history of photography is not just about individual photographers in their moment of inspiration, something implied by Cartier-Bresson’s lasting theory of the “decisive moment.” The many conversations and research hours showed me Magnum’s photography was the product of a “decisive network”, one that included writers, spouses, secretaries, picture editors, dark room assistants, publishers, corporate leaders, and museum curators who helped photographers attain their success. Interweaving analyses of Magnum’s published work with the conversations that unfolded in its offices and in its correspondence in the 1940s and 1950s, I delved into the many instances in which Magnum staff helped photographers by editing their film, laying out their pictures into stories, and pitching their work to clients.

And while the popular image of Magnum has, for decades, been linked to the courageous, generally wartime, exploits of its male photographers over those early decades of the collective’s history, Magnum’s “decisive network” included many more women than have previously been noticed. Women were always at the heart of Magnum’s operations; they just weren’t necessarily behind the cameras. Early Magnum needed Rita Vandivert’s organizational abilities and the sales prowess of Maria Eisner (pictured here at a 1950 meeting in the Paris office), honed during her time running Alliance Photo. The two became President and Secretary-Treasurer of the cooperative when it was created. Within weeks, Magnum also hired secretaries, book-keepers, couriers, picture editors, sales agents, and picture librarians – many of whom were women. Equally important were photographers’ wives, who helped their husbands by captioning, researching their stories, and maintaining their picture archives.

Consider the first description of Magnum’s business plan, sent in a letter to the founders by Magnum’s President Rita Vandivert on May 22, 1947. “The way Capa sees it working out for himself and the others is this,” she began:

…he makes a deal with a publication to send him somewhere, gets expense money, etc. and does the agreed number of stories or pages for them. Then he shoots as much material as he can on the side, keeping closely in touch with both offices so that we know what he can get… the photographer must know what the magazines are interested in, what they are hoping to get, and the agency girls must know at all times what the photographers are up to (except on their evenings off).

With a tinge of glamour and mischief, Vandivert’s letter demonstrated that three things were central to Magnum: the needs of its clients, entrepreneurialism and creativity on the part of the photographer, and close communication between photographers and office staff.

As at Life, where women occupied so many of the photo editing and photo research positions, the Magnum “girls” whom Vandivert referred to were front and center. They made daily editing and captioning decisions and negotiated fees and sales in a magazine world dominated by male editors. While photographers worked in faraway places, Magnum’s largely female staff offered personal and professional support through weekly, and sometimes, daily letters. After examining photographers’ films and contact sheets, staff assessed the technical quality of their work and made concrete recommendations for the future. They told them, for instance, when it was time to realign their lenses or when a photographer needed to shoot more vertical color to increase his chances of getting a cover.

Staff also studied the picture market and told photographers about different magazines’ tastes, some of which can sound appallingly insensitive to a contemporary readers, but which also allow us to eavesdrop on the kinds of conversations happening in editorial meetings at mid-century. Life, Vandivert told Chim in 1947, wanted really dramatic pictures of postwar Europe, “pictures of starving hordes and corpses everywhere.” Writing to George Rodger a decade later, Paris bureau chief Trudy Feliu told Rodger that Illustrated preferred “first-person stories by photographers. They are mostly of the type ‘The Zulus mauled me but I got my picture’… Not always too tasteful but you’ve certainly got enough to make their hair stand on end, which is what they like.” Photographers’ letters, in turn, were often grateful and gracious. Asking for even more feedback on their films and published stories, photographers showed that they trusted the staff’s aesthetic and journalistic sense and that they relied on them in every stage of a story’s production.

They were not good at these tasks because they were women, but because they had experience from established media institutions. Upon leaving Magnum, many continued to work with pictures. What we see when we scrutinize this period – and this ‘decisive network’ – is that Magnum influenced visual culture not only through the pictures it put into circulation, but also via the actual people who worked in its offices.

In 1948, Joan Bush (sitting across from Eisner in the 1950 Paris meeting photo) left Life to work in Magnum’s Paris office, where she sold stories to French editors and coordinated photographers’ assignments. Upon leaving Magnum in 1950, she became a photo editor at Picture Post and then the World Health Organization, where she eventually led its international media presence.

Jinx Witherspoon worked as an editor at Ladies’ Home Journal before joining George Rodger as research assistant, collaborator, and, in 1953, wife. In the early 1950s, she devoted months to editing pictures and organizing files as a part-timer in both the New York and Paris offices, and even helped Rodger get an assignment to travel through Africa for the Economic Cooperation Administration. She accompanied him on all of his long journeys through the Middle East and Africa and worked on his films, captions, and archive once they settled in England.

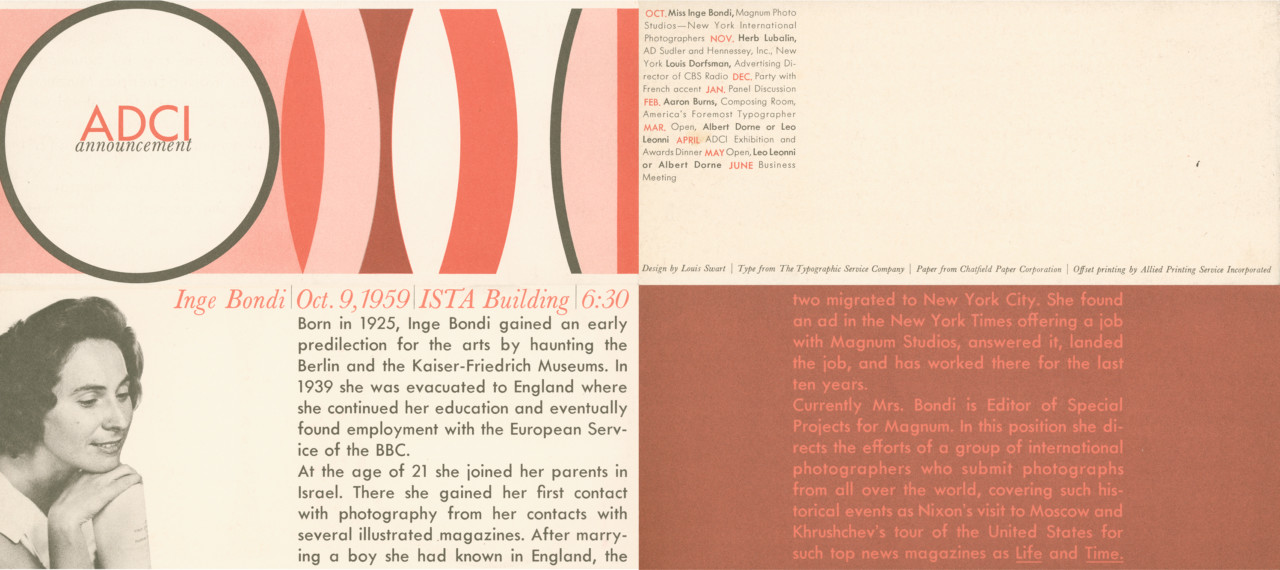

And Inge Bondi (bottom left in image above), hired as a secretary in 1950, came with experience from the BBC public relations office in Palestine. She quickly expanded her portfolio of responsibilities and by 1958 was Magnum’s Editor of Advertising and Special Projects. In that capacity, she forged lucrative relationships between Magnum and Madison Avenue advertising agencies and was responsible for overseeing Magnum’s inclusion in a range of prestigious museum exhibitions in the United States.

I had the opportunity to meet Bondi, who now lives in Princeton, New Jersey, in early 2015 and correspond with her over the years as I was writing this book. I began to think of her as Magnum’s Peggy Olson, the character played by Elizabeth Moss in HBO’s hit series Madmen, who begins as Don Draper’s secretary and ends up a powerful ad executive in her own right.

Bondi, as I discovered, helped steer Magnum into a new and highly lucrative sphere of the picture business by focusing on public relations and advertising photography. Hired as a secretary in 1950, the young Inge Bondi had developed close relationships with the first generation of Magnum photographers, including Capa, Chim, Ernst Haas, and Elliott Erwitt. Like them, she was European-born and Jewish, and had recently adopted New York as her new home. Capa was the first to take on Bondi as a protégé, helping her learn how magazines work and keeping her involved in Magnum’s finances as well as its editorial projects. And she learned to edit films by working with the photographers Ernst Haas and Werner Bischof, who, like her, spoke German.

In 1955, Bondi became Magnum’s Secretary Treasurer. The responsibility of overseeing Magnum’s finances inspired her to find new ways to grow the organization’s severely limited operating budget and capital reserve. Along the way, she also became responsible for Magnum’s print sales and museum and gallery projects. By 1958, she was a Magnum stockholder with a new title: Editor of Exhibitions, Special Projects, and Advertising.

Advertising was, notoriously, a man’s industry, where women were hired mostly to work on campaigns and products targeting their sex. But those gender divisions did not apply at Magnum, where Bondi took the reins of the advertising market writ large. She mingled at the Art Directors’ Club in New York and regularly called on three dozen art directors to talk about campaigns and assignments. Another four hundred art directors heard from Bondi via her Magnum publicity mailings, which extolled photographers’ recent advertising and industrial commissions and often resulted in new assignments.

Through Bondi’s efforts, Magnum’s client network grew to include the leading advertising agencies of the day, including J. Walter Thompson; Doyle Dane and Bernbach; and Ogilvy, Benson & Mather. A 1959 roster that Bondi casually titled “Some Magnum photographed advertisements and campaigns” listed 42 separate clients, including four governments, three car companies, two banks, and Pepsi Cola. The following year, Bondi calculated that Magnum had completed 90 advertisements for 24 different accounts. Between 1957 and 1960, Magnum’s advertising revenue more than doubled. Bondi, who in 1959 sold $30,000 worth of advertising jobs (the equivalent of $263,000 in 2019), played no small role in that growth.

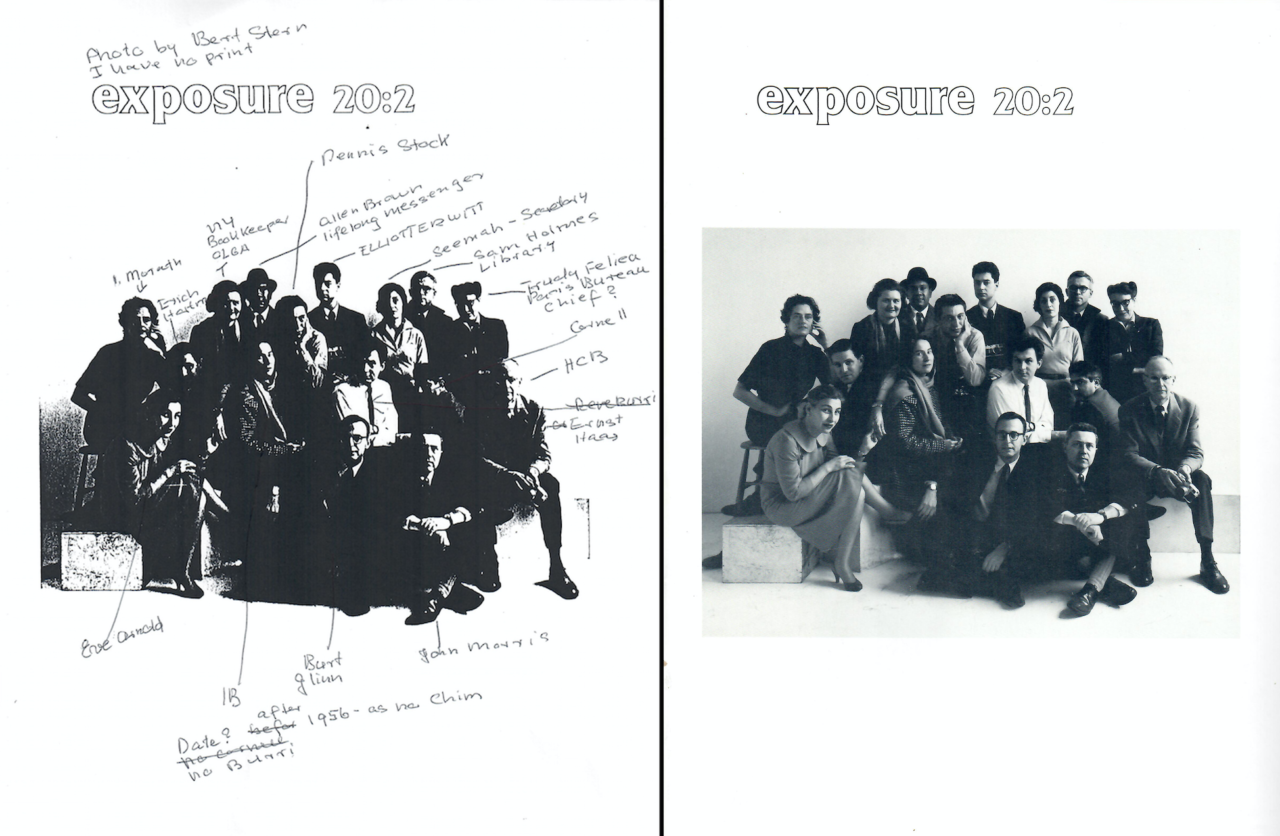

Inadvertently, Bondi also helped me to understand, and visualize, Magnum as a network. After our first meeting in February 2015, Bondi sent me a few Xeroxed documents, including a group photograph of Magnum that the Society for Photographic Education (SPE) had published on the cover of its magazine in 1982. The bodies and faces were dark and blotchy, but Bondi was able to make out each one.

Bondi pointed out that Olga Brodsky, the New York book-keeper, was standing next to Allen Brown, the messenger who picked up film from labs and delivered stories to editors. Behind Seemah, a secretary in New York, was Sam Holmes, the manager of Magnum’s picture library and advocate of stock photo sales. To his left was Magnum’s Paris bureau chief Trudy Feliu, who worked with all the European sales agents and editors. Sitting on the floor was the Executive Editor John Morris, arms crossed and expression firm. And at the center, looking coolly at the camera, was Inge Bondi herself – the ad woman of Magnum.

For an organization that deals in photographs, images are quite bad at capturing the complex and collaborative nature of Magnum’s history. Yet Bondi’s diagram comes close to a summation of my project. With its nearly 1:1 ratio of photographers to staff hiding in plain sight, this unintended network visualization asks viewers to see individual Magnum photographers alongside the other people who made the agency function. With its black spots and crossed out names and dates, this far-from-perfect copy (of a 1957 photograph, printed in a 1982 magazine, and decoded in 2015) is indicative of the multiple phases of reproduction and repurposing that Magnum’s images went through. The fact that Bondi saved this old magazine cover among many other documents is a testament to the kind of extensive documentation and record-keeping involved in running a photographic agency, and inadvertently, creating an archive. And that Bondi decided I would find value in this image shows what made her so good at her job. Once again, the right picture got to the right person.

The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market is available through Amazon and Barnes and Noble in print or e-versions. To receive a 30% discount, order directly from UC Press and use source code 17M6662 at checkout.